Julebukking (Gå julebukk) is a Christmas tradition of Scandinavian origin.[1]

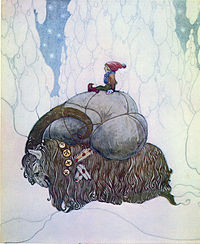

by John Bauer (1912)

Between Christmas and New Year's Day, people wearing face masks and costumes (Julebukkers) would go door to door, where neighbors receiving them attempt to identify who is under the disguise. In one version of Julebukking, people go from door to door singing Christmas songs. After they have sung, they are usually awarded with candy. Another tradition requires that at least one person from the visited household join the band of Julebukkers and continue to the next household.[2]

In certain aspects, the custom resembled the modern-day tradition of Halloween trick-or-treating.[3][4] Julebukkers will often disguise their voices and body language to further the masquerade. Offering people holiday treats and something to drink is customary. Once identities are known and the food is eaten, the Julebukkers continue to the next home.[5]

History

editThe earliest form of Julebukking was a pre-Christian pagan ritual. The tradition of the Yule goat (Julebukk) is commonly believed to have originated in Norway, at a time when pagans worshiped Thor, the god who traveled in his chariot drawn by two goats.[6] During the Yule holiday, they would disguise their appearance by dressing in a goatskin and go from house to house carrying a goat head.[7]

Christian missionaries modified the tradition and divorced its meaning from Paganism. The Yule Goat became one of the oldest Scandinavian and Northern European Yule and Christmas symbols and traditions. In Scandinavia, the figure of the Yule Goat remains a common Christmas ornament. It is often made out of straw, has a red ribbon around its neck, and is found under the Christmas tree.[8]

German and Scandinavian immigrants brought this tradition to America.[9] Though the practice of Julebukking may be dying out in Europe, it can still be observed on occasion in rural communities in America with large populations of people of Scandinavian descent, such as in Petersburg, Alaska, Ketchikan, Alaska and Rushford, Minnesota.[10][11] The tradition previously existed in all the Nordics.[12]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Julebukk (Dictionary of American Regional English) Retrieved 14 November 2012

- ^ Jul (Store norske leksikon) Retrieved 14 November 2012

- ^ Julebukking or Christmas Fooling Retrieved 5 August 2013

- ^ Vernon county museum notes: Julebukking a tradition in Norwegian communities Retrieved 5 August 2013

- ^ Julebukk (Juleleker) Archived 2010-12-08 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 14 November 2013

- ^ Local julebukkers keep Norwegian tradition alive Retrieved 5 August 2013

- ^ Julebukk (About My Little Norway) Retrieved 14 November 2012

- ^ Christmas in Norway (Christmas Traditions Around the World) Retrieved 14 November 2012

- ^ Burning the Christmas Goat by Alaska Dispatch Retrieved 5 August 2013

- ^ Julebukking, also known as Christmas fooling (Hendricks, MN) Archived 2006-10-30 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 14 November 2012

- ^ Howard Sherpe (December 30, 2014). "Julebukking: A Dying Tradition". Jackson County Chronicle. Retrieved October 8, 2015.

- ^ Noraker, Anne Marit; Bråten, Ole Aastad. "Julebukk og julegeit". Valdresmusea. Retrieved 3 July 2023.

Related Reading

edit- Rossel, Sven H.; Elbrönd-Bek, Bo (1996) Christmas in Scandinavia (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press) ISBN 0-8032-3907-6