The jungle owlet (Glaucidium radiatum) or barred jungle owlet is native to the Indian Subcontinent. The species is often found singly, in pairs or small groups, and they are usually detected by their calls at dawn and dusk. There are two subspecies, with that found in the Western Ghats sometimes considered a full species.

| Jungle owlet | |

|---|---|

| |

| Jungle owlet in Mangaon, Maharashtra | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Strigiformes |

| Family: | Strigidae |

| Genus: | Glaucidium |

| Species: | G. radiatum

|

| Binomial name | |

| Glaucidium radiatum | |

| |

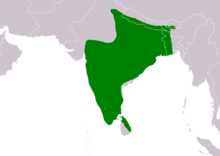

| Range of G. radiatum Extant, resident

| |

| Synonyms | |

|

Taenioglaux radiatum | |

Description

editThis small owlet has a rounded head and is finely barred all over. There is no clear facial disk and the wings are brownish and the tail is narrowly barred in white. There are two subspecies, the nominate form is found in the plains of India and Sri Lanka, while G. r. malabaricum of the Western Ghats is shorter tailed and shows more brown on the head. It has been suggested that the latter may warrant full species status.[3]

The plumage on the upper parts is dark black-brown barred with white. The wing coverts have white and rufous patches. The primaries and secondaries are dark brown and barred with pale chestnut. The lower side is whitish or pale rufous barred with black. There is a whitish patch on the chin, upper breast and centre of the abdomen. The iris is yellow, the bill and tarsi are greenish with black claws.[4]

In Sri Lanka, the chestnut-backed owlet (Glaucidium castanonotum) was once included as a subspecies but this is elevated to full species. It is found in the wet zone ,whereas G. radiatum is found in drier forests.[3]

Habitat and distribution

editThey are found in habitats ranging from scrub forest to deciduous and moist deciduous forests. They are found south of the Himalayas and in some parts of the Himalayas up to an elevation of 2,000 m (6,600 ft), extending from Dalhousie in the west, east to Bhutan.[5]

Behaviour and ecology

editThis owlet is mainly active at dawn and dusk, but is known to call and fly during the daytime as well. The call is distinctive and consists of a rapid series of prao..prao.prao-prao-prao that increases and then fades in volume before ending abruptly. At their daytime roosts, they may be mobbed by drongos, treepies and sunbirds.[3] During the day, young nestlings produce tick calls not unlike that of a pale-billed flowerpecker.[6]

The Jungle Owlets roost inside tree cavities and when disturbed they freeze and appear like a dead tree stump. They sometimes perch prominently on wires or bask in the morning sun before retiring to their roost. Also, they have been known to capture small Phylloscopus warblers during the day, although their peak foraging hours are an hour before sunrise and after sunset. Their diet consists of insects, small birds, reptiles, and rodents.[4][7]

The breeding season in India is March to May, and they nest in the hollow of a tree at a height of 3 to 5 m (10 to 16 ft). The typical clutch consists of four eggs (three eggs in G. r. malabaricum).[3][4]

References

edit- ^ a b BirdLife International (2016). "Glaucidium radiatum". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22689283A93225315. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ Tickell, S.R. (1833). "Untitled". Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal. 2: 572. Archived from the original on 2023-09-03. Retrieved 2023-12-20.

- ^ a b c d Rasmussen, PC & JC Anderton (2005). Birds of South Asia: The Ripley Guide. Volume 2. Smithsonian Institution & Lynx Edicions. p. 245.

- ^ a b c Whistler, Hugh (1949). Popular Handbook Of Indian Birds (4th ed.). Gurney and Jackson, London. pp. 348–350.

- ^ Handbook of the birds of India and Pakistan. Vol. 3 (2nd ed.). New Delhi: Oxford University Press. 1981. pp. 286–288.

- ^ Neelakantan,KK (1971). "Calls of the Malabar Jungle Owlet (Glaucidium radiatum malabaricum)". J. Bombay Nat. Hist. Soc. 68 (3): 830–832.

- ^ Mason, C. W. (1911). Maxwell-Lefroy, H (ed.). The food of birds of India. Imperial Department of Agriculture in India. p. 194.