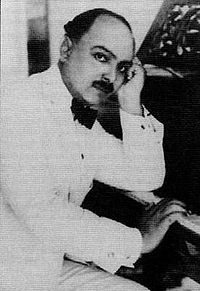

Justin Elie (1 September 1883 – 2 December 1931) was a Haitian composer and pianist.[1] He is one of the best-known composers outside of Haiti.[2]

Biography

editJustin Elie was born in Cap-Haïtien.[1] He studied piano with Ermine Faubert from 1889 to 1894 and he joined the Institution Saint-Louis de Gonzague in Port-au-Prince in 1894. In 1895, he migrated to France and enrolled at the Cours Masset, a preparatory school for the Conservatoire de Paris in Paris.[1] He meets Antoine François Marmontel before his death in 1898. In 1901, Justin Elie was admitted to the Conservatoire de Paris. He studied with Charles-Wilfrid de Bériot for piano, Émile Pessard for harmony, and Paul Vidal for the musical composition.[1][3]

Return to the Americas

editIn 1905 he returned to Haiti, where he met his colleague Ludovic Lamothe, composer and musician like himself, with which he will play and make a tour of major cities.[3]

Latin America

editIn 1909 and 1910, he toured Latin America and has given recitals in many of the islands Caribbean (Cuba, Curaçao, Jamaica, Puerto Rico, Saint Thomas) and South America (Venezuela).[3] In 1916, he also recorded his own ''Dance Tropical" on Piano roll for the Aeolian Company of New York's Duo-Art system.

Like Ludovic Lamothe, Justin Elie was reintroducing the méringue. It became a national symbol and a form of resistance to the US occupation, the country suffered since 1915. Ludovic Lamothe drew from African roots to express the meringue, while Justin Elie instead turned to the Amerindian past of Saint-Domingue. He composed several méringues: Le Chant du Barde Indien et La Mort de l'Indien (Song of the Indian bard and The Death of the Indian). In 1920, he composed Méringue Populaire.[3]

The influence of Vodou is also present in the Elie's compositions, such as in Cléopâtre, poetry drama set in four arrays.[3]

United States

editOn 12 September 1922, Elie left Haiti for the United States and settled in New York. He contacted the publishers of music and publish new partitions, such as Légende Créole, Prière du soir, Invocation No. 2; Ismao-o !; Les Chants de la montagne No. 1; Nostalgie: Les Chants de la montagne No. 2; Nocturne: Les Chants de la montagne No. 3; Kiskeya.[3] Elie's adaptations of Haitian melodies into miniatures led him to various performances in international concert venues, notably in the Carnegie Hall where he performed with his duet dancer called Hasoutra in 1923.[4] In 1925, he composed the frames of silent films, including The Phantom of the Opera (Somers), and in 1931, the generic of a New York radio show, The Lure of the Tropics.[3]

Death

editElie died suddenly of a cerebral hemorrhage on 3 December 1931 when he was composing Fantaisie Tropicale in New York City. His body was returned to Haiti.[3]

Notable works

edit- Suite Babylon: 1. Pas des Odalisques (orchestre). Arrangement: C. J. Roberts. Edition: Carl Fischer (1925)

- Suite Babylon: 2. Bayaderes (orchestre). Arrangement: C. J. Roberts. Edition: Carl Fischer (1925)

- Suite Babylon: 3. La reine de la nuit (orchestre). Arrangement: C. J. Roberts. Edition: Carl Fischer (1925)

- Suite Babylon: 4. Orgie (orchestre). Arrangement: C. J. Roberts. Edition: Carl Fischer (1925)

- Firefly Fancies (orchestre). Edition: Carl Fischer (1929)

- La Nuit des andes (orchestre). Edition: Carl Fischer (1930)

- Isma-o!: Les chants de la montagne No. 1 (orchestre). Arrangement: C. J. Roberts. Edition Carl Fischer (1922)

- Melida (A Creole Tropical Dance) (orchestre). Arrangement: C. J. Roberts. Edition Carl Fischer (1927)

- Prière du soir (L'invocation No. 2) (orchestre). Arrangement: C. J. Roberts. Edition Carl Fischer (1922)

References

edit- ^ a b c d Horne, Aaron, ed. (1996). Brass Music of Black Composers: A Bibliography. p. 89. ISBN 0313298262. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Kuss, Malena, ed. (2007). Music in Latin America and the Caribbean: An Encyclopedic History Reannounce. p. 254. ISBN 9780292709515. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Largey, Michael, ed. (2006). Vodou Nation: Haitian Art Music and Cultural Nationalism. p. 120. ISBN 0226468631. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- ^ Walden, Joshua S., ed. (2014). Sounding Authentic: The Rural Miniature and Musical Modernism. p. 15. ISBN 9780199334667. Retrieved 4 November 2015.