The Kahuzi-Biega National Park (Swahili: Hifadhi ya Taifa ya Kahuzi-Biega, French: Parc national de Kahuzi-Biega) is a protected area near Bukavu town in eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is situated near the western bank of Lake Kivu and the Rwandan border. Established in 1970 by the Belgian photographer and conservationist Adrien Deschryver, the park is named after two dormant volcanoes, Mount Kahuzi and Mount Biega, which are within its limits. With an area of 6,000 square kilometres (2,300 sq mi), Kahuzi-Biega is one of the biggest national parks in the country. Set in both mountainous and lowland terrain, it is one of the last refuges of the rare species of Eastern lowland gorilla (Gorilla beringei graueri), an endangered category under the IUCN Red List. The park is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, inscribed in 1980 for its unique biodiversity of rainforest habitat and its eastern lowland gorillas. In 1997, it was listed on the List of World Heritage in Danger because of the political instability of the region, an influx of refugees, and increasing wildlife exploitation.[1]

| Kahuzi-Biéga National Park | |

|---|---|

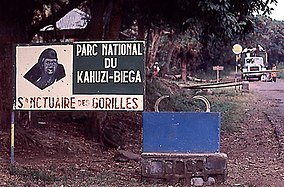

Park entrance | |

| Location | Democratic Republic of the Congo |

| Coordinates | 2°30′0″S 28°45′0″E / 2.50000°S 28.75000°E |

| Area | 6,000 km2 (1,500,000 acres) |

| Established | 1970 |

| Governing body | l'Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature (ICCN) |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | x |

| Designated | 1980 (4th session) |

| Reference no. | 137 |

| Region | Africa |

| Endangered | 1997–present |

Geography

editThe park lies west of the Bukavu town in South Kivu Province,[2] covering an area of 6,000 km2 (2,300 sq mi). A small part of the park is in Mitumba Mountain range of the Albertine Rift in the Great Rift Valley, and the larger part is in lowland terrain.[3] A corridor of 7.4 km (4.6 mi) width joins the mountainous and lowland terrain.[2] The eastern part of the park is the smaller mountainous region measuring 600 km2 (230 sq mi); the larger part measures 5,400 km2 (2,100 sq mi) and consists mainly of lowland stretching from Bukavu to Kisangani, drained by the Luka and Lugulu rivers which flow into the Lualaba River.[3] Two dormant volcanoes are set within the park's limits and lend their names to it: Kahuzi (3,308 m (10,853 ft)) and Biéga (2,790 m (9,150 ft)).[2]

The park receives an average annual precipitation of 1,800 mm (71 in). The average maximum temperature in the area is 18 °C (64 °F) while the minimum is 10.4 °C (50.7 °F).[4]

Legal status

editThe earliest reserve, Zoological and Forest Reserve of Mount Kahuzi, was created on 27 July 1937 by the then Governor General of the Belgian Colonial administration.[4] That reserve has been part of the Kahuzi-Biega National Park since November 1970. Five years later, the park was extended to cover 6000 km2.[5]

The park was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1980,[3] under Criterion (x) for its unique habitat of rainforest and diversity of the mammal species, particularly the eastern lowland gorillas, Gorilla beringei graueri.[3]

Biodiversity

editThe park has a rich diversity of flora and fauna. As of a survey conducted in 2003 by the Wildlife Conservation Society, it protects roughly 349 species of birds and 136 species of mammals.[3] Over 1,178 plant species have been observed in the highland regions of the park alone.[3] Because of its varied topography and habitat types, Kahuzi-Biega National Park is also a hotspot of plants and vertebrate endemism for.[3]

Flora

editThe park's swamps, bogs, marshland and riparian forests on hydromorphic ground at all altitudes are rare worldwide. The western lowland sector of the park is dominated by dense Guineo-Congolian wet equatorial rainforest, part of the Northeastern Congolian lowland forests ecoregion,[6] with an area of transition forest between 1,200 metres (3,900 ft) and 1,500 metres (4,900 ft). The eastern mountainous sector includes continuous forest vegetation from 600 metres (2,000 ft) to over 2,600 metres (8,500 ft), and is one of the rare sites in Sub-Saharan Africa which demonstrates all stages of the low to highland transition, including six distinguishable primary vegetation types: swamp and peat bog, swamp forest, high-altitude rainforest, mountain rainforest, bamboo forest and subalpine heather.[3] The montane rain forests are part of the Albertine Rift montane forests ecoregion.[6] Mountain and swamp forest grows between 2,000 metres (6,600 ft) and 2,400 metres (7,900 ft), bamboo forest grows between 2,350 metres (7,710 ft) and 2,600 metres (8,500 ft), and the summits of Mounts Kahuzi and Biéga above 2,600 metres (8,500 ft) have subalpine heather, dry savannah, and grasslands, as well as the endemic plant Senecio kahuzicus.[3][7]

Fauna

editThe national park protects a greater diversity of mammal species than any other national park in the Albertine Rift.[3] Among the 136 species of mammals identified in the park, the eastern lowland gorilla is the most prominent. According to a 2008 status report of the DR of Congo, the park had 125 lowland gorillas, a marked reduction from the figure of 600 gorillas of the pre-1990's conflict period, and consequently the species has been listed in the endangered list. The park is the last refuge of this rare species.[8] According to the census survey of eastern lowland gorillas reported by the Wildlife Conservation Society in April 2011, at least 181 gorillas were recorded in the park.[9]

Other primates include the eastern chimpanzee, and several Cercopithecinae, Colobinae and owl-faced monkey. Some of the mammals include the bush elephant, bush buffalo, hylochere and bongo, eastern needle-clawed galago, Maclaud's horseshoe bat, Ruwenzori least otter shrew, and Alexander's bush squirrel.[3] Two species of genet (animal) that live within the park are endemic to the Congo Basin: the aquatic genet and the giant forest genet.[3]

Of the 349 bird species identified within the park, at least 42 of them are endemic to the region, including the threatened Albertine owlet. Other native bird species include the Yellow-crested Helmet-shrike (Prionops alberti), the Congo peafowl (Afropavo congensis), the African green broadbill (Pseudocalyptomena graueri), and the Rockefeller's sunbird (Nectarinia rockefelleri).[3]

The species of fauna listed under the IUCN Red List as threatened include:[3]

- African forest elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis)

- Albertine owlet (Glaucidium albertinum)

- Eastern chimpanzee (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii)

- Mount Kahuzi climbing mouse (Dendromus kahuziensis)

- Maclaud's horseshoe bat (Rhinolophus maclaudi)

The species of fauna listed under the IUCN Red List as least concern or near threatened include:[3]

- Lowland bongo (Tragelaphus eurycerus eurycerus)

- African forest buffalo (Syncerus caffer nanus)

- Hippopotamus (Hippopotamus amphibius)

- Giant forest hog (Hylochoerus meinertzhageni)

- Leopard (Panthera pardus)

- Ruwenzori otter shrew (Micropotamogale ruwenzorii)

- Olive baboon (Papio anubis)

A 2020 survey of the freshwater fish in the park and its three drainage basins identified 147 species, 11 of which were found to be endemic to the Lowa River basin, and 7 of which were previously undescribed.[10] Cyprinidae was by far the largest family represented.

Conservation

editThe park, under the management of the Institut Congolais pour la Conservation de la Nature, has a basic management and surveillance structure.

However, the park's 1975 expansion, which included inhabited lowland areas, resulted in forced evacuations with about 13,000 people of the tribal community of Shi, Tembo and Rega affected and refusing to leave.[3] Cooperation by the communities living around the park and employment of the Twa people to enforce park protection was pursued by the park authorities. In 1999, a plan was developed to protect the people and the resources of the park.[11]

In a survey conducted between 2015 and 2016, the national park rangers reported a low level of satisfaction with the job, highlighting low salaries, lack of support from the authorities, and poor living conditions.[12]

Illegal artisanal mining of Coltan happens in the park, thus damaging the deep forest cover.[13]

Human rights abuses

editIn 2019, national park rangers allegedly engaged in violence against Batwa who returned to the park in 2018. This included the alleged killing of a number of residents, the burning of villages, as well as the use of sexual violence against indigenous residents.[14]

In 2022, the African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights ruled that the Democratic Republic of the Congo violated the human rights of Batwa people according to the African Charter,[15] including by evicting them from ancestral territories without prior consent when the Kahuzi-Biega National Park was created.[16] The case was filed in 2015 but the decision was made public in June 2024.[17]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Debonnet, G. & Hillman-Smith, K. (2004). "Supporting protected areas in a time of political turmoil: the case of World Heritage Sites in the Democratic Republic of Congo". Parks. 14 (1): 9–16.

- ^ a b c Barume 2000, p. 68-.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Kahuzi-Biega National Park". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. Retrieved 27 October 2013.

- ^ a b Barume 2000, p. 68.

- ^ Barume 2000, p. 70.

- ^ a b "Kahuzi-Biega National Park". DOPA Explorer. Accessed 22 March 2022. [1]

- ^ Forests For the Future: Local Strategies for Forest Protection, Economic Welfare and Social Justice, by Paul Wolvekamp, page 154, Zed Books (January 1, 2000), ISBN 1856497577.

- ^ "Kahuzi-Biega National Park". World Heritage Site Organization. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ "Gorillas surviving against the odds in Kahuzi-Biega". Gorilla Organization. 21 April 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2013.

- ^ Kisekelwa, Tchalondawa; Snoeks, Jos; Vreven, Emmanuel (2020). "An annotated checklist of the fish fauna of the river systems draining the Kahuzi‐Biega National Park (Upper Congo: Eastern DR Congo)". Journal of Fish Biology. 96 (3): 700–721. doi:10.1111/jfb.14264. ISSN 0022-1112.

- ^ Barume 2000, pp. 72–77.

- ^ Spira, Charlotte; Kirkby, Andrew E.; Plumptre, Andrew J. (2019). "Understanding ranger motivation and job satisfaction to improve wildlife protection in Kahuzi–Biega National Park, eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo". Oryx. 53 (3): 460–468. doi:10.1017/S0030605318000856. ISSN 0030-6053.

- ^ Diaz-Struck and Poliszuk 2012

- ^ "Investigation documents murder, rape by DRC national park guards". Al Jazeera. 2022. Retrieved 2024-10-21.

- ^ "Fortress Conservation: Can a Congo Tribe Return to Its Forest?". Yale E360. Retrieved 2024-11-15.

- ^ Surma, By Katie (2024-07-30). "International Human Rights Commission Condemns 'Fortress Conservation'". Inside Climate News. Retrieved 2024-11-15.

- ^ Bascomb, Bobby (2024-08-02). "Indigenous Batwa win human rights victory over eviction from DRC park". Mongabay Environmental News. Retrieved 2024-11-15.

Further reading

edit- Barume, Albert Kwokwo (2000). Heading Towards Extinction?: Indigenous Rights in Africa : the Case of the Twa of the Kahuzi-Biega National Park, Democratic Republic of Congo. IWGIA. ISBN 978-87-90730-31-4.

- Wolvekamp, Paul; Usher, Ann Danaiya; Paranjpye, Vijay; Ramnath, Madhu. (1999). "10 The Challenge of Conservation in KahuziBiega National Park, DRC". Forests for the future: local strategies for forest protection, economic welfare and social justice. London: Zed Books. p. 151. ISBN 978-1-85649-757-2.

External links

edit- Media related to Kahuzi-Biega National Park at Wikimedia Commons

- Kahuzi-Biéga National Park travel guide from Wikivoyage

- Kahuzi Biega National Park Official Website