Konstantinos Mitsotakis (Greek: Κωνσταντίνος Μητσοτάκης, romanized: Konstantínos Mitsotákis, IPA: [konsta(n)ˈdinoz mit͡soˈtacis]; 31 October [O.S. 18 October] 1918 – 29 May 2017) was a Greek politician who was Prime Minister of Greece from 1990 to 1993.[1] He graduated in law and economics from the University of Athens. His son, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, was elected as the Prime Minister of Greece following the 2019 Greek legislative election.

Konstantinos Mitsotakis | |

|---|---|

| Κωνσταντίνος Μητσοτάκης | |

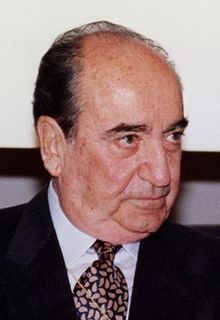

Mitsotakis in 1992 | |

| Prime Minister of Greece | |

| In office 11 April 1990 – 13 October 1993 | |

| President | Christos Sartzetakis Konstantinos Karamanlis |

| Preceded by | Xenophon Zolotas |

| Succeeded by | Andreas Papandreou |

| Minister of Foreign Affairs | |

| In office 14 April 1992 – 7 August 1992 | |

| Preceded by | Antonis Samaras |

| Succeeded by | Michalis Papakonstantinou |

| In office 10 May 1980 – 21 October 1981 | |

| Prime Minister | Georgios Rallis |

| Preceded by | George Rallis |

| Succeeded by | Ioannis Charalambopoulos |

| President of New Democracy | |

| In office 1 September 1984 – 3 November 1993 | |

| Preceded by | Evangelos Averoff |

| Succeeded by | Miltiadis Evert |

| Minister of the Aegean | |

| In office 8 August 1991 – 13 October 1993 | |

| Preceded by | George Misailidis |

| Succeeded by | Kostas Skandalidis |

| Minister of Coordination | |

| In office 10 May 1978 – 10 May 1980 | |

| Prime Minister | Konstantinos Karamanlis |

| Preceded by | George Rallis |

| Succeeded by | Ioannis Boutos |

| In office 17 September 1965 – 22 December 1966 | |

| Prime Minister | Stefanos Stefanopoulos |

| Preceded by | Dimitrios Papaspirou |

| Succeeded by | Ioannis Paraskevopoulos |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 18 October 1918 Halepa, Kingdom of Greece |

| Died | 29 May 2017 (aged 98) Athens, Greece |

| Political party | Liberal (1946–1961) Centre Union (1961–1974) Independent (1974–1977) New Liberal (1977–1978) New Democracy (1978–2017) |

| Spouse | |

| Children | Dora Kyriakos Alexandra Katerina |

| Alma mater | University of Athens |

Family and personal life

editMitsotakis was born on 31 October 1918[2][3] in Halepa suburb, Chania, Crete, into an already powerful political family, linked to the distinguished statesman Eleftherios Venizelos on both sides. His grandfather Kostis Mitsotakis (1845–1898), a lawyer, journalist and short-time MP of then Ottoman-ruled Crete, founded the Liberal Party, then "Party of the Barefeet" (Κόμμα των Ξυπολήτων) with Venizelos, and married the latter's sister, Katigo Venizelou, Constantine's grandmother. The 1878 Pact of Halepa, granting an Ottoman Crete a certain level of autonomy, was signed in his very home. His father Kyriakos Mitsotakis (senior) (1883–1944), also MP for Chania in the Greek Parliament (1915–20) and leader of the Cretan volunteers fighting with the Greek army in the First Balkan War, married Stavroula Ploumidaki, daughter of Charalambos Ploumidakis, the first Christian mayor of Chania and an MP at the time of the Cretan State, himself a first cousin of Eleftherios Venizelos.[4]

Mitsotakis was married to Marika Mitsotakis (née Giannoukou) from 1953 until her death on 6 May 2012.[5][6] They had four children.[6] His son, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, is the Prime Minister of Greece and since January 2016 leader of the conservative New Democracy party (a position previously held by Mitsotakis), and was a government minister in 2013–15. His first daughter, Dora Bakoyannis, ND Member of Parliament, founder and president of Democratic Alliance party, was the mayor of Athens (2003–2006) and the Minister of Foreign Affairs from 2006 to 2009. His second daughter Alexandra Mitsotakis Gourdain is a Greek civil society activist. His third daughter is Katerina Mitsotakis.

Mitsotakis's interests outside politics included Cretan antiquities and a passion for preserving the environment. He developed a large collection of Minoan and other Cretan antiquities, which he and his wife donated to the Greek state. He was also very interested in promoting reforesting of Greece, including in particular the mountains of Crete.

Venizelos/Mitsotakis family tree

edit| Main members of the Venizelos/Mitsotakis family.[7] Prime Ministers of Greece are highlighted in light blue. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Political career

editMitsotakis was elected to the Greek Parliament for the first time in 1946, standing for the Liberal Party in his native prefecture of Chania, Crete. He followed most of the old Liberal Party into Georgios Papandreou's Center Union in 1961. But in 1965 he led a group of dissidents, known as the "July apostates", who crossed the floor to bring about the fall of Papandreou's government, which earned him the long-time hatred of Papandreou loyalists as well as a significant part of Greek society. He was arrested in 1967 by the military junta but managed to escape to Turkey with a help of Turkish foreign minister İhsan Sabri Çağlayangil and lived in exile with his family in Paris, France, until his return to Greece in 1974, following the restoration of democracy.

In 1974 he campaigned as an independent and failed to be elected to Parliament. He was re-elected in 1977 as founder and leader of the small Party of New Liberals and in 1978 he merged his party with Constantine Karamanlis's New Democracy (ND) party. He served as Minister for Coordination from 1978 to 1980, and as Minister for Foreign Affairs from 1980 to 1981.

The ND government was defeated by Andreas Papandreou's PASOK in 1981, and in 1984 Mitsotakis succeeded Evangelos Averoff as ND leader. He and Andreas Papandreou, the son of Georgios Papandreou, dominated Greek politics for the next decade: their mutual dislike dated back to the fall of Georgios Papandreou's government in 1965.

Mitsotakis soundly defeated Papandreou, embroiled in the Bank of Crete scandal, in the June 1989 election. PASOK lost 36 seats in one of the largest defeats of a sitting government in modern Greek history. However, in a controversial move, Papandreou's government had modified the election system just two months earlier, to require a party to win 50 percent of the vote in order to govern alone. Thus, even though ND was the clear first-place party, with 20 more seats than PASOK, it only won 44 percent of the vote, leaving it six seats short of a majority.

After Mitsotakis failed to garner enough support to form a government, Court of Cassation president Yannis Grivas became acting prime minister and presided over new elections in November 1989. This election yielded the same result as in June. ND finished 20 seats ahead of PASOK, but only won 46.2 percent of the vote and came up three seats short of a majority. Former Bank of Greece president Xenophon Zolotas became interim prime minister and presided over fresh elections in April 1990. The result was the same as the two 1989 elections. ND won a landslide victory, finishing 27 seats ahead of PASOK. However, Mitsotakis was still unable to govern alone, as ND won 150 seats, one short of a majority. Finally, the lone MP from Democratic Renewal agreed to a coalition with ND, allowing Mitsotakis to form government by one seat.

In social policy family benefits were introduced for families with 3 children or more. IKA pension replacement rates, however, were reduced from 80% to 60%, while the retirement age was raised to 65 for both men and women who entered the workforce in 1993.[9]

Mitsotakis's government moved swiftly to cut government spending as much as possible, privatise state enterprises and reform the civil service. In foreign policy, Mitsotakis took the initiative to have Greece formally recognize the state of Israel, and moved to reopen talks on American bases in Greece and to restore confidence among Greece's economic and political partners. In June 1990, Mitsotakis became the first Greek Premier to visit the United States since 1974. He promised to meet Greece's NATO obligations, to prevent the use of Greece as a base for terrorism, and to stop the rhetorical attacks on the United States that had been Papandreou's hallmark. Mitsotakis also supported a new dialogue with Turkey, but made progress on the Cyprus dispute a prerequisite for improvement on other issues.

Papandreou, cleared of charges arising from the Bank of Crete scandal in a 7–6 vote at the Eidiko Dikastirio (Special Court), criticised Mitsotakis's government for its economic policies, for not taking a sufficiently strict position over the naming dispute with the newly independent Republic of Macedonia (Mitsotakis favored a composite name such as "Nova Macedonia", for which he was accused at the time of being too lenient) as well as over Cyprus, and for being too pro-American. The heightened public irritation over the Macedonia naming issue caused several ND parliament members, led by Antonis Samaras, to withdraw their support from Mitsotakis's government and form a new political party, Political Spring (Πολιτική Άνοιξη , Politiki Anixi). Mitsotakis' government restored the pre-1989 electoral system, which allowed Papandreou's PASOK to obtain a clear parliamentary majority after winning the premature 1993 elections and return to office. Mitsotakis then resigned as ND leader, although he remained the party's honorary chairman.

In January 2004 Mitsotakis announced that he would retire from Parliament at the 7 March election, 58 years after his first election.

Death

editMitsotakis died on 29 May 2017 in Athens, aged 98 of natural causes[10][11][12] Four days of national mourning were declared.[13] His state funeral was held on 31 May 2017 and he was buried in Chania.[14][15]

Honours

editSource:[16]

- Australia: Companion of the Order of Australia (Honorary) (6 January 1992).[17]

- Finland: Grand Cross of the Order of the Holy Lamb (10 May 1991).[18]

- Portugal: Military Order of Christ

- Italy: Order of Merit of the Italian Republic

- Cyprus: Order of Makarios III

References

edit- ^ "Διατελέσαντες Πρωθυπουργοί". 27 December 2016.

- ^ Eleni Panagiotarea (30 July 2013). Greece in the Euro: Economic Delinquency or System Failure?. ECPR Press. p. 176. ISBN 978-1-907301-53-7.

- ^ "Ίδρυμα Κωνσταντίνος Κ. Μητσοτάκης - Ρίζες - Νεανικά Χρόνια - Αντίσταση". www.ikm.gr. Archived from the original on 1 June 2017. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- ^ Constantine Mitsotakis institute. "Biography - Roots". Archived from the original on 2 September 2017. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ Papapostolou, Anastasios (6 May 2012). "Former First Lady of Greece Marika Mitsotakis Dies at 82". Greek Reporter. Retrieved 26 May 2012.

- ^ a b Papapostolou, Anastasios (6 May 2012). "Marika Mitsotakis, wife of former Greek PM, dies Dies at 82". Boston.com. Associated Press. Retrieved 26 May 2012.[dead link]

- ^ Constantine Mitsotakis institute. "Biography – Roots". Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ Stavroula Ploumidaki is also a first cousin, once removed, of Eleftherios Venizelos

- ^ Ideologues, Partisans and Loyalists Ministers and Policymaking in Parliamentary Cabinets by Despina Alexiadou

- ^ "Former Greek Prime Minister Constantine Mitsotakis dies aged 98". Reuters. 29 May 2017.

- ^ "Constantine Mitsotakis, Who Forged Greek-EU Ties, Dies at 98". Bloomberg.com. 29 May 2017 – via www.bloomberg.com.

- ^ "Constantine Mitsotakis, Former Prime Minister of Greece, Dies at 98". The New York Times. 29 May 2017.

- ^ Τριήμερο εθνικό πένθος: Τι είναι και τι προβλέπει - Πότε κηρύσσεται

- ^ Makris, A. (31 May 2017). "Thousands Attend Konstantinos Mitsotakis' Funeral Service in Athens - GreekReporter.com".

- ^ "Funeral Service for Constantine Mitsotakis at the Metropolitan Cathedral of Athens: (Video & Photo Gallery) - The National Herald". www.thenationalherald.com. Archived from the original on 11 October 2017. Retrieved 1 June 2017.

- ^ Some derived from photograpic coverage of his funeral [1] [2]

- ^ "It's an Honour - Honours - Search Australian Honours". www.itsanhonour.gov.au.

- ^ "Arkkipiispa Johannekselle Kreikan arvokkain kunniamerkki". Helsingin Sanomat (in Finnish). 11 May 1991. p. A 4.

Further reading

edit- Wilsford, David, ed. Political leaders of contemporary Western Europe: a biographical dictionary (Greenwood, 1995) pp. 318–23.

External links

edit- The Konstantinos Mitsotakis Foundation/Ίδρυμα Κωνσταντίνος Μητσοτάκης Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine