The korrigum (Damaliscus lunatus korrigum), also known as Senegal hartebeest,[2] is a subspecies of the topi, a large African antelope.[1]

| Korrigum | |

|---|---|

| |

| In Waza National Park, Cameroon | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Alcelaphinae |

| Genus: | Damaliscus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: | D. l. korrigum

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Damaliscus lunatus korrigum (Ogilby, 1837)

| |

| |

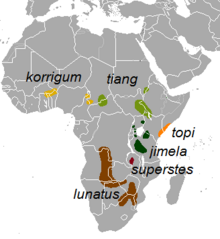

| Range in yellow | |

| Synonyms | |

Taxonomy

editAn 1822–1824 British expedition across the Sahara to the ancient kingdom of Bornu,[4] returned with single set of horns of an antelope known in the language of that land as a korrigum.[3] These horns were classified as a new species by William Ogilby in an article in the journal Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London dated 1836, but published in 1837.[2][3]

Description

editKorrigan were said to differ from the tiang subspecies based on the tail tuft being more bushy, and the pelage being more reddish. In the tiang, the patches of dark hair on the legs were said to be somewhat larger. In the Belgian Congo, a topi was shot in the 19th century which is intermediate between these two.[3]

Morphometrically, korrigan and tiang were found to be indistinguishable.[5]

Range and conservation

editKorrigum formerly occurred from southern Mauritania and Senegal to western Chad, but has undergone a dramatic decline since the early 20th century because of displacement by cattle and uncontrolled hunting for meat.[6] In 1998 the IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group claimed the species no longer occurs in Mauritania, Mali, Senegal and the Gambia, they probably no longer occur in northern Togo, Nigeria or western Chad, except as vagrants.[7] The IUCN copied the same text in their 2008[6] and 2016 assessments.[1]

Based on a 2004 estimation of the population of two national parks,[8] Waza National Park and Pendjari National Park (and associated parks), the resident population in these two parks was estimated at maximally 2,650 animals. Based no that, the conservation status of the taxon was assessed as 'vulnerable' by the IUCN in 2008, because it was deemed as uncertain whether the species will experience a population decline of 20% in the next two generations (14 years).[6] In 2016, based on the exact same 2004 information, but using new definitions of assessment statuses which now subtract a significant portion of this National Park population under the assumption that these are not mature adults, the IUCN now claimed the animal was 'endangered'.[1]

The 2004 population number used by the IUCN in 2016 is not the total population, but the IUCN claims that 95% of the total population occurs in these two parks.[1] The 95% claim appears to be a misreading of the 2004 report, in which it is stated that an estimated 95% of the range of the antelope in the country of Benin is estimated to fall within protected areas.[8] There was a large fall in population number in Waza NP before 2007. In 2013 korrigum were also found to continue to exist in northeast Ghana.[1]

Topi populations have also continued to occur in Zakouma National Park in Chad, as well as in the surrounding game hunting blocks outside the park,[9] where they have been growing.[10] The topi here are called korrigan[9] or tiang,[11] and have been assigned to the subspecies tiang.[11]

There are also large populations in the Niwa area bordering the Bouba Ndjida National Park in Cameroon,[12] as well as throughout the park itself.[13]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (2 August 2016). "Damaliscus lunatus ssp. korrigum". Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ a b c Grubb, P. (2005). Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M. (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-8221-4. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ a b c d Lydekker, Richard (1908). The game animals of Africa. London: R. Ward, limited. pp. 116–121. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.21674. OCLC 5266086.

- ^ Natural History Museum (BM) (19 April 2013). "Clapperton, Bain Hugh (1788-1827)". JSTOR. Ithaka. Retrieved 28 April 2021.

- ^ Heller, Rasmus; Frandsen, Peter; Lorenzen, Eline Deirdre; Siegismund, Hans R. (September 2014). "Is Diagnosability an Indicator of Speciation? Response to "Why One Century of Phenetics Is Enough"". Systematic Biology. 63 (5): 833–837. doi:10.1093/sysbio/syu034. hdl:10400.7/567. PMID 24831669.

- ^ a b c IUCN SSC Antelope Specialist Group (30 June 2008). "Damaliscus lunatus ssp. korrigum". Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ^ East, Rod; IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group (1998). "African Antelope Database" (PDF). Occasional Paper of the IUCN Species Survival Commission. 21: 200–207. Retrieved 23 April 2021.

- ^ a b Chardonnet, Bertrand (November 2004). "An update on the status of korrigum (Damaliscus lunatus korrigum) and tiang (D. l. tiang) in West and Central Africa". IUCN/SSC Antelope Specialist Group Antelope Survey Update. 9: 66–76.

- ^ a b "Exclusive New Area Plains Game Hunt 1x1 / Chad". Book Your Hunt. 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Chad - Main Details". Convention on Biological Diversity. United Nations Environment Programme. 2020. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ a b Capacity4dev Team (16 March 2017). "Parc de Zakouma, Tchad - Damaliscus lunatus". Capacity4dev. European Union. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Cameroon Savanna Hunt / Cameroon". Book Your Hunt. 2021. Retrieved 29 April 2021.

- ^ "Bouba Ndjidal National Park". European Union. 28 October 2010. Archived from the original on 12 April 2013. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

Further reading

edit