The German Democratic Republic, or GDR (German: Deutsche Demokratische Republik, or DDR), a state in Central Europe that existed from 1949 to 1990 before being absorbed by the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG), was dominated by heterosexual norms. However, East Germany decriminalised homosexuality during the 1960s, followed by increasing social acceptance and visibility.

LGBTQ rights in German Democratic Republic | |

|---|---|

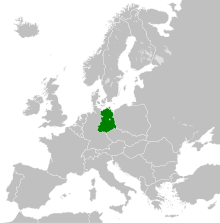

Territory of East Germany (green) in 1957 | |

| Status | Homosexuality decriminalised from 1968; equalized age of consent from 1987 |

| Gender identity | State-sponsored sex reassignment surgery for those over 18; No legislation addressing the recognition of a trans individual's new gender |

| Military | LGBT individuals allowed to serve openly |

| Family rights | |

| Adoption | LGBT individuals allowed to adopt |

Legal situation

editHomosexuality

editWhen the GDR was founded in 1949, it inherited Paragraph 175a of the Nazi legal code, along with many other pre-existing laws. Paragraph 175 also became part of the law of West Germany. Paragraph 175a banned ‘unnatural desire’ between men, with a clause protecting against the ‘seduction’ of men and boys under the age of 21.[1] After attempts at legal reform in 1952 and 1958, homosexuality was officially decriminalised in the GDR in 1968, although Paragraph 175 ceased to be enforced from 1957.[2] The ruling Socialist Unity Party (SED) viewed it neither as an illness nor legitimate sexual identity, but as a long-term biological problem.[1] In 1968, Paragraph 151 criminalised homosexual relations between adult men and those under 18 years old, establishing an unequal age of consent compared to that of heterosexuals, which was 14 years old for both sexes. This provision was struck down by the Supreme Court in 1987, arguing that an unequal age of consent excluded homosexuals from socialist society and the civil rights guaranteed to them. In July 1989, the age of consent for all sexual relations was set at 14.[3]

In an international context, decriminalisation aided the GDR's progressive image, bringing the country into line with ‘more progressive (in this matter) socialist states like Czechoslovakia and Poland, and pre-empting West German decriminalisation by one year’. However, the lives of homosexuals in the GDR changed little; for the most part, they remained invisible to wider society.[1]

Transsexual rights

editThe GDR allowed for both men and women over the age of 18 to receive government-sponsored sex reassignment surgery as its healthcare system was free and fully nationalized. Transgender individuals were also allowed to marry other people and adopt children.[4][better source needed] However, the GDR lacked any legislation addressing the recognition of a trans person's new gender. Consequently, this meant that after German reunification in 1990, subsequent constitutional interpretations of the Transsexual Law in the German basic law did not have to refer to East German provisions on transsexual rights.[5]

Social and political situation

editIn the five years following the Uprising of 1953 in East Germany, the GDR Government instituted a program of "moral reform" to build a solid foundation for the new socialist republic in which masculinity and the traditional family were championed, while abortion and homosexuality, seen to contravene "healthy mores of the working people", continued to be prosecuted. Same sex activity was "alternatively viewed as a remnant of bourgeois decadence, a sign of moral weakness, and a threat to the social and political health of the nation." Gays and lesbians in the GDR experienced intense feelings of isolation in this social landscape, with those in rural areas having it even worse than urban residents. One of the founders of the lesbian publication Frau Anders, recalled:

- "I come from a provincial town myself, from Suhl. At lesbian get-togethers I met other lesbians, who had hunkered down on their own somewhere and were very lonely. Then they would travel for hundreds of kilometres just to meet a pen friend, only to find that it wasn't worth it. They were in hiding, they spent their whole lives in hiding."[1]

For many queer people, this intense isolation compounded into invisibility in which not just representation, but vocabulary was absent from society. In response to an interview question on her perception of the social acceptability of coming out, Barbara, a woman from East Berlin, explained:

- “I am sure that in the GDR I would never have come together with a woman, that wouldn't have been possible. For that, the rejection and intolerance was too great. Of that I am sure... No, I couldn't have had a coming out in the GDR. I wouldn't have known, where one finds women, where, where lesbians are. I didn't know that lesbians were called ‘lesbians’.”[1]

Queer visibility

editIn the early years of the GDR, queer spaces were commonly pushed beneath formal state structures. The FDJ (Free German Youth) did not accept homosexual members, and city councils made it difficult for meeting spaces and events to be set up. In the 1970s, visibility began to improve slightly, with various queer institutions taking hold in and around Berlin. The HIB (Homosexuelle Interessengemeinschaft Berlin) was established in 1973 with the belief that ‘homosexual emancipation is part of the success of socialism', aiming to educate society in this vein.[1] In a more informal context, meetings at Charlotte von Mahlsdorf’s large inherited home outside Berlin evolved into a fortnightly support group discussing coming out, STDs, and other queer issues combined with drinking and dancing. Charlotte was East Germany's best-known trans person, and she became involved with the Stasi both as a subject of surveillance and a suspected informer herself.[1] A gathering at her establishment, which was the first organized national event for lesbians, was planned by Ursula Sillge, but blocked by police in April 1978.[1]: 124 [6]: 42 Thereafter, the support group was barred from meeting at Von Mahlsdorf's. The HIB met a similar fate at the same time due to both Stasi surveillance and subsequent intervention and the group's significant organisational difficulties.[1]

This same year, the Church-State Agreement allowed for queer rights groups to gather in Protestant Churches, which allowed them to organise and mobilise more effectively. Though there was tension between religious institutions and these queer working groups, the opportunity was invaluable in that it allowed them to host ‘coming-out’ discussions, parents’ nights, and gay and lesbian social events.[1] As well, these working groups played an important role in remembering the gay and lesbian victims of the Holocaust by laying a wreath at the Buchenwald memorial site in 1983, followed by similar demonstrations at other Holocaust memorials. The SED responded negatively, arguing that homosexuality could not be considered a ‘separate problem’ in the history of the Holocaust, adding that ‘many homosexual concentration camp inmates were criminals, and the number of homosexuals murdered in concentration camps was a very small part of those killed by the fascists.’[1]

A 1985 shift in GDR policy led to many groups becoming more formalised. The 11th SED Congress reassessed the party's approach homosexuals to focus on integration, symbolising a radical attempt to adjust to the changing social norms within society. While the party itself remained rather ambivalent towards queer people, relegating minority-group institutions outside of state structures could have been interpreted as delegitimising the state, so many party officials sought to develop a more integrative policy towards homosexuals. At this time too, the party revisited its stance on homosexual victims of the Holocaust within the legacy of antifascism. In a review of the 1989 film Coming Out, the only feature film made in the GDR that had an LGBT theme,[7] the Minister for Culture explained the film's political significance to the recognition of homosexuals and communists as victims who fought together against their fascist tormentors.[1]

The change in official position led to the establishment of gay and lesbian clubs inside the context of state institutions, a move which activists had been attempting since the 1970s.[3] For example, the circle of non-church affiliated activists around Sillge, who had been meeting since the demise of the HIB, successfully petitioned for permission to occupy a permanent space at the Mittzwanziger-Klub on Veteranenstraße in 1986. Because the space was only free on Sundays, that became the regular meeting day and from 1987, the group was called the Sunday Club. Though the club lost the space in 1987, the following year it was able to move into the Kreiskulturhaus (District Cultural Center) in the Mitte district of Berlin.[8][9]: 47 The Sunday Club did not gain official status as a legal association until 1990, after the fall of the Berlin Wall,[9]: 48 though it had strong support from the community. Similar groups and clubs were later created in Dresden, Leipzig, Weimar, Gera, Magdeburg, Potsdam, Halle and a second club in Berlin.[3]

Furthermore, the Kulturbund allowed the Magnus Hirschfeld Arbeitskreis (Magnus Hirschfeld Study Group) to organise under the guise of promoting scientific endeavours in sexuality. State organisations such as the family planning services also began training staff for issues with sexual identity. The FDJ, after 1985, began discussing homosexuality and bisexuality and creating events for the community. In the FDJ Youth Festival of 1989, the central council of the FDJ instructed a positive reception to the creation of new spaces and clubs. The FDJ also allowed gay chapters within their ranks.[10]

However the SED itself remained fairly ambivalent regarding queer issues, identities and recognition, partly due to a belief that non-engagement with the subject would 'solve' it. Therefore, the 1985 policy reform was mainly left up to the interpretation of local party officials and homophobia was relatively commonplace. However, the state's approach to homosexuality was still amongst the most progressive for its time. For example, the former first secretary of the central council of the FDJ Eberhard Aurich argued for the importance of integrating the community into the public domain:

- “In accordance with our goals in the FDJ-Public Program 40 years of the GDR. . .we attribute much importance to the integration of homosexual youth as equal citizens. . . . I can assure you that the FDJ will continue to give great attention toward the complete equality of homosexual youth and other citizens in its diverse forms of political and ideological work.”[11]

In 1988 the German Hygiene Museum, working in co-operation with East German gay and lesbian activists, commissioned the state film studio DEFA to make the documentary film Die andere Liebe (The Other Love), which was intended to convey official state acceptance of homosexuality. It was the first East German film that dealt with the topic.[12][13]

AIDS

editThe AIDS crisis, as it was experienced by queer communities in the West, did not penetrate the GDR to the same extent. By 1989 only 84 people had been diagnosed with AIDS, compared to 37,052 in the FRG.[14] While this statistic was conducted by a German AIDS organisation 10 years after, there is always the possibility that diagnoses do not necessarily denote the actual number of cases. Nevertheless, the lack of contact with the West and general isolation of the population meant that the AIDS epidemic was not as prevalent amongst the community. The SED hence treated the crisis as a problem of the capitalist West. In the later years of the GDR, however, AIDS was a peripheral concern of gay men in East Berlin, aware that West Berliners travelling to the city's Eastern sector had contact with the virus, but this concern never existed to the same extent as in the West.[15]

The only HIV/AIDS prevention documentary produced in the GDR was Liebe ohne Angst (Love without fear), which the German Hygiene Museum commissioned DEFA to make in 1989. The film follows the AIDS prevention group Aidsgesprächskreises (AIDS discussion circle) at a disco as they discuss AIDS prevention and interview an AIDS expert who clarifies that it is not a "gay disease".[16][17]

Culture

editThe state remained to have a centralised control over media, often censoring queer content and thereby preventing any representation thereof.[citation needed] The most common mentions of queer-related themes were the pejorative use of schwul (gay) and lesbisch (lesbian) in jokes.[18]

In the early years of the regime, advice writers in state media often deemed homosexuality as a perversion, pathology or deviance. This suffocated much queer culture, and the SED generally avoided talking about homosexuality altogether. It was only in 1965 that the central committee declared itself in favour of depiction of sex in literature and culture, yet it must have adhered to the perfect socialist narrative of romance, which undoubtedly excluded any form of non-heterosexual love. As a result, many activists turned to the Church printing press to create works as that did not suffer from this censorship, although some refused to work with the Church due to ideological reasons.[10]

Despite the physical separation of Berlin after 1961, the West remained culturally influential in queer material. Rosa von Praunheim’s film "Nicht der Homosexuelle ist pervers, sondern die Situation, in der er lebt" (It Is Not the Homosexual Who Is Perverse, But the Society in Which He Lives) was shown on Western television in 1973 and represented a key moment in the West German gay liberation movement. In the East, such a movement did not exist, but the film proved powerful for many queer East Germans, who remember the film as the first representation of non-heteronormative relations in the media.[1]

After the 1985 party position to integrate homosexuals into the community, a knock on effect was felt in GDR arts and culture. A new openness was felt in the media, literature, print and broadcast media. In 1987 the TV program Visite broke many taboos in openly discussing homosexuality as a natural part of human sexuality. In 1988, the state film studio, DEFA, on commission from the German Hygiene Museum, produced the film Die andere Liebe (The other love), the first GDR documentary on homosexuality, and in 1989, released the only GDR feature film on the subject, Coming Out, by the gay director Heiner Carow.[12][13]

Notable figures

editRudolf Klimmer was a notable gay figure amongst the GDR community, practicing as a psychologist and sexologist as well as a gay activist. After the war he joined the SED and was a prominent figure in pushing for the removal of Paragraph 175.[1]

Eduard Stapel is another prominent figure, a theologian and leader of the Lesbian and Gay Church movement. In 1982 he founded the Homosexuality Working Group with Christian Pulz and Matthias Kittlitz in the Evangelical Student Centre in Leipzig. He continued to advocate for the queer community within the ecclesiastical sphere, and outside of it. The Stasi saw him as the main organiser of the gay rights movement in the GDR and its many groups and organisations that were removed from formal state institutions.[1] In April 1994 Stapel was interviewed by gay history researcher Kurt Stapel, who published a transcript in his 1994 book Schwuler Osten.[19]

Charlotte von Mahlsdorf was East Germany's best-known trans woman. She lived outside Berlin in an estate, which she converted into a local Gründerzeit museum. There, she hosted informal queer gatherings, which were eventually shut down by the Stasi.[15]

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o McLellan, Josie (September 2011). Love in the Time of Communism: Intimacy and Sexuality in the GDR. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521727617.

- ^ Bauer, J. Edgar (1998). "Der Tod Adams. Geschichtsphilosophische Thesen zur Sexualemanzipation im Werk Magnus Hirschfelds" [The Death of Adam. Historical-philosophical theses on sexual emancipation in the work of Magnus Hirschfeld]. 100 Jahre Schwulenbewegung. Dokumentation einer Vortragsreihe in der Akademie der Künste [100 years of the gay movement. Documentation of a lecture series in the Academy of Arts] (in German). Berlin: Verlag Rosa Winkel. p. 55. ISBN 978-3861490746.

- ^ a b c Hillhouse, Raelynn J. (1990). "Out Of The Closet Behind The Wall: Sexual Politics And Social Change In The GDR". Slavic Review. 49 (4): 585–596. doi:10.2307/2500548. JSTOR 2500548. S2CID 146928669.

- ^ "FTM Newsletter, June 1990". FTM Newsletter. June 1990. p. 3.

- ^ Knott, Gregory. "Transsexual Law Unconstitutional: German Federal Constitutional Court Demands Reformation of Law Because of Fundamental Rights Conflict" (PDF). Saint Louis University Law Journal: 26.

- ^ Wallbraun, Barbara (2015). "Lesben im Visier der Staatssicherheit" [Lesbians in the Sights of State Security] (PDF). In Lubinski, Laura (ed.). Das Übersehenwerden hat Geschichte: Lesben in der DDR und in der friedlichen Revolution. Das Übersehenwerden hat Geschichte: Lesben in der DDR und in der friedlichen Revolution, Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung Sachsen-Anhalt 8 May 2015 in Halle (Saale) (in German). Halle (Saale), Germany: Heinrich Böll Foundation. pp. 26–50. OCLC 951732653. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 November 2021. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Coming Out". DEFA Film Library. Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Dobler, Jens; Schmidt, Kristine; Nellißen, Kay (20 January 2015). "Sonntags im Club" [Sundays at the Club]. lernen-aus-der-geschichte (in German). Berlin, Germany: Agentur für Bildung – Geschichte, Politik und Medien e.V. Archived from the original on 27 September 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ a b Tammer, Teresa (2013). Schwul bis über die Mauer: Die Westkontakte der Ost-Berliner Schwulenbewegung in den 1970er und 1980er Jahren [Gay over the Wall: The East Berlin Gay Movement's Contacts with the West in the 1970s and 1980s] (Masterarbeit) (in German). Berlin, Germany: Institut für Geschichtswissenschaften, Humboldt University of Berlin. No. 541240. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ^ a b Huneke, Samuel Clowes (April 18, 2019). "Gay Liberation Behind the Iron Curtain". Boston Review. Archived from the original on July 2, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ Eberhard Aurich, letter to Dr. Kurt Bach, Hohenmölsen, GDR, 13 Oct. 1988, cited in Kurt Bach, letter to the editor, Dorn Rosa 2 (February 1989): 37,

- ^ a b Frackman, Kyle (2018). "Shame and Love: East German Homosexuality Goes to the Movies'". In Frackman, Kyle; Steward, Faye (eds.). Gender and Sexuality in East German Film: Intimacy and Alienation. Rochester, NY: Camden House.

- ^ a b "The Other Love (Die andere Liebe)". DEFA Library website. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Herrn, Rainer (1999). Schwule Lebenswelten im Osten. Andere Orte, andere Biographien. Kommunikationsstrukturen, Gesellungsstile und Leben schwuler Männer in den neuen Bundesländern [Gay lifestyles in the East. Different places, different biographies. Communication structures, social styles and life of gay men in the new federal states] (in German). Berlin: Deutsche AIDS-Hilfe. p. 20. ISBN 978-3930425358.

- ^ a b Lemke, Jürgen; Borneman, John (2011). Gay voices from East Germany. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. pp. 145–150.

- ^ "Love Without Fear (Liebe ohne Angst)". DEFA Library website. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ "Sex, Gender and Videotape: Love, Eroticisim and Romance in East Germany, 19-24 July 2015" (PDF). University of Massachusetts news archive. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 October 2020. Retrieved 5 October 2020.

- ^ Pence, Katherine; Betts, Paul (2011). Socialist Modern. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- ^ Starke, Kurt (1994). Schwuler Osten: Homosexuelle Männer in der DDR [Gay East: Homosexual Men in the GDR] (in German). Berlin: Ch. Links. pp. 91–110. ISBN 3-86153-075-9.