LIPIA (Arabic: معهد العلوم الإسلامية والعربية في إندونيسيا, romanized: Ma'had al-ʻulumi al-Islamiyyah wal 'arabiyah fi Indunisia; Indonesian: Lembaga Ilmu Pengetahuan Islam dan Bahasa Arab; English: Islamic and Arabic College of Indonesia) is a Saudi educational institution established in Jakarta, Indonesia. The college is a branch of the Imam Muhammad ibn Saud Islamic University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The main purpose is to teach Arabic and Islam. The college has been accused of promoting a fundamentalist view of Islam, harbouring political Islamists and Salafists.[1]

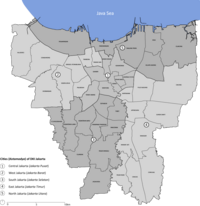

Location of LIPIA in Jakarta | |

| Founder(s) | Imam Muhammad ibn Saud Islamic University, Riyadh |

|---|---|

| Established | 1980 |

| Focus | Education |

| President | Dr. Khaled Muhammad Ad-Diham |

| Head | Dr. Muhammad al-Mu'tiq |

| Owner | Saudi Arabia |

| Formerly called | LPBA |

| Address | Jalan Buncit Raya 5A, South Jakarta |

| Location | , |

| Website | www |

History

editThe College was founded in 1980 to provide education with concentrations in Arabic and Islamic religion for Indonesian students with approval from the Royal Court, No. 5/n/26710. The name of the college was Arabic Teaching Institute ("Lembaga Pendidikan Bahasa Arab") until 1986. The college gives scholarship to its top students to continue their education to Imam Muhammad ibn Saud Islamic University in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The most well known organizations that serve as primary conduits of Saudi funding in Indonesia are the Indonesian Islamic Propagation Council (DDII) and LIPIA.[2]

The vision of the LIPIA establishment is to be the distinguished leader in creative learning, teaching and research in Islamic and Arabic sciences. The salafi movement in early 1990s in Indonesia began to develop on university campuses, but mostly gained impetus with the arrival of other Middle-eastern educated and Soviet-Afghan War veterans.[3] Following the 1979 Shia revolution in Iran and the Iranian/Saudi hegemonic conflict that ensued, Indonesia took on major strategic importance for Saudi religious politics.[4] LIPIA not only helps Saudi Arabia to influence Indonesian society, it also provides a gateway to all of Southeast Asia.[4]

All lectures taught in LIPIA are delivered in Arabic language and about 80–90 percent of the lecturers are from Saudi Arabia. It has very high acceptance standard, where only 200 students are accepted out of 2000 applicants. Once they are admitted, they do not need to pay any tuition, even they are paid stipends. 200 students graduate from the college every year.[5]

The college teaches Wahhabi Madhab, a branch of Salafi.[2][6] Every student has to learn the teachings of Ibn Taimiyah. The college was also influenced by Al-Ikhwan al-Muslimin,[5] and some of its lecturers were influenced by the Muslim brotherhood doctrine. Many of the alumni later became Salafi activists, preachers or teachers. Some of the alumni then open other institutions based on Wahhabism and funded by Saudi Arabia.[7][8] Ulil Abshar Abdalla noted that LIPIA's Wahhabism curriculum predisposes its graduates to adopt an attitude hostile to the local Indonesian culture and Muslim practices.[8] Top male students, who are willing to learn the Koran by heart and can be expected to propagate Saudi ideas in Southeast Asia, are given grants for the Imam Muhammad bin Saud University in Riyadh. Their stay in Riyadh is intended to make them more committed to Wahhabi values and more sympathetic to Saudi rule.[4]

Program

editThe program is in the format of courses that include learning the Quran and Arabic language free of charge to people who are interested in participating. The program is held on Saturday and Sunday on a weekly basis. The classes are held for two Semester (24-week or 192 hours) which are adjusted to LIPIA school calendar.[9] Lessons in Jakarta transfer deeply rooted discourses from Saudi Arabia to Indonesia, with teachers required to impart the superiority of the Hanbali School of Law.[4]

Participants who have passed the final exam will be given a certificate of LIPIA at the end of the course activities.[9] Everyday life on campus is permeated by commandments and prohibitions intended to shape the students according to the Saudi model: Wearing jeans, loud laughter, listening to music, and watching television are all prohibited. In contrast, the common dress style for Salafi men - ankle-length linen pants, sandals, goatees and the use of neem sticks (miswak) - are all encouraged. Women are expected to veil themselves completely.[4]

References

edit- ^ Varagur, Krithika (2020-04-16). "How Saudi Arabia's religious project transformed Indonesia". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ a b von der Mehden, Fred R. (December 1, 2014). "Saudi Religious Influence in Indonesia". Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- ^ Farish A. Noor; Yoginder Sikand; Martin van Bruinessen, eds. (2008). "Ahmad-Noor A. Noor". The Madrasa in Asia: Political Activism and Transnational Linkages:Volume 2 of ISIM series on contemporary Muslim societies. Amsterdam University Press. p. 303. ISBN 978-9-053567104.

- ^ a b c d e Kovacs, Amanda (2014). "Saudi Arabia Exporting Salafi Education and Radicaling Indonesia's Muslims" (PDF). GIGA Focus. 7. Leibniz-Institut für Globale und Regionale Studien. ISSN 2196-3940. Retrieved February 10, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Bubalo, Anthony; Fealy, Greg (2007). Jejak Kafilah: Pengaruh Radikalisme Timur Tengah di Indonesia (in Indonesian). Mizan Pustaka. pp. 94–101. ISBN 978-9-79433-476-8.

- ^ Kinzer, Stephen (June 11, 2017). "Saudi Arabia is destabilizing the world". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 5 September 2017. Retrieved 14 June 2017.

- ^ Hasan, Noorhaidi (2006). Laskar Jihad: ISIM dissertations. SEAP Publications. p. 266. ISBN 978-0-877277408.

- ^ a b Ramakrishna, Kumar (2014). Islamist Terrorism and Militancy in Indonesia: The Power of the Manichean Mindset. Springer. p. 269. ISBN 978-9-812871947.

- ^ a b "LIPIA: Profile". Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 23, 2015.