Full Metal Jacket is a 1987 war film directed and produced by Stanley Kubrick from a screenplay he co-wrote with Michael Herr and Gustav Hasford. The film is based on Hasford's 1979 autobiographical novel The Short-Timers. It stars Matthew Modine, R. Lee Ermey, Vincent D'Onofrio, Adam Baldwin, Dorian Harewood, and Arliss Howard.

| Full Metal Jacket | |

|---|---|

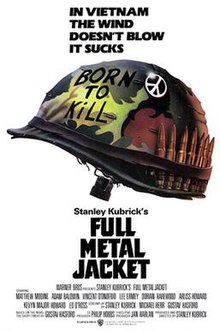

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Screenplay by |

|

| Based on | The Short-Timers by Gustav Hasford |

| Produced by | Stanley Kubrick |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | Douglas Milsome |

| Edited by | Martin Hunter |

| Music by | Vivian Kubrick (as Abigail Mead) |

Production companies |

|

| Distributed by |

|

Release dates |

|

Running time | 116 minutes[1] |

| Countries |

|

| Languages |

|

| Budget | $16.5–30 million[3][4] |

| Box office | $120 million[5] |

The storyline follows a platoon of U.S. Marines through their boot camp training at Marine Corps Recruit Depot Parris Island, South Carolina. The first half of the film focuses primarily on privates J.T. Davis and Leonard Lawrence, nicknamed "Joker" and "Pyle" respectively, who struggle under their abusive drill instructor, Gunnery Sergeant Hartman. The second half portrays the experiences of Joker and other Marines in the Vietnamese cities of Da Nang and Huế during the Tet Offensive of the Vietnam War.[6] The film's title refers to the full metal jacket bullet used by military servicemen.

Warner Bros. released Full Metal Jacket in the United States on June 26, 1987. It was the last of Kubrick's films to be released during his lifetime. The film received critical acclaim, grossed $120 million against a budget of $16.5–30 million and was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay.[7] The film was also nominated for two BAFTA Awards, and Ermey was nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture for his performance. In 2001, the American Film Institute placed the film at number 95 in its poll titled "AFI's 100 Years...100 Thrills."[8]

Plot

editDuring the Vietnam War, a group of USMC recruits arrive for basic training at Parris Island. Drill instructor Gunnery Sergeant Hartman uses harsh methods to train them for combat. Among the recruits are the wisecracking J. T. Davis, who receives the name "Joker" after interrupting Hartman's introductory speech with an impression of John Wayne, and the overweight and dim-witted Leonard Lawrence, whom Hartman nicknames "Gomer Pyle."

During boot camp, Hartman names Joker as squad leader and puts him in charge of helping Pyle improve. One evening while doing a hygiene inspection, Hartman notices that Pyle's footlocker is unlocked. As he inspects it for signs of theft, he notices a jelly doughnut inside, blames the platoon for Pyle's infractions and adopts a collective punishment policy by which any infraction committed by Pyle will earn a punishment for everyone else in the platoon. The next night, the recruits haze Pyle with a blanket party in which Joker reluctantly participates. Following this, Pyle appears to reinvent himself as a model recruit, showing particular expertise in marksmanship. This pleases Hartman but worries Joker, who believes Pyle may be suffering a mental breakdown after seeing Pyle talking to his rifle. The recruits graduate, but the night before they leave Parris Island, Joker, who is on fire watch duty, discovers Pyle in the barracks latrine loading his service rifle with live ammunition, executing drill commands, and loudly reciting the Rifleman's Creed. Hartman is awakened by the commotion and attempts to intervene by ordering Pyle to give the rifle to him, but Pyle fatally shoots Hartman and then commits suicide in front of Joker.

Following Hartman's death, Joker becomes a sergeant in January 1968 and is based in Da Nang for the newspaper Stars and Stripes alongside his colleague Private First Class "Rafterman," a combat photographer. The Tet Offensive begins and the base is attacked, but holds. The following morning, Joker and Rafterman are sent to Phu Bai, where Joker searches for and reunites with Sergeant "Cowboy," a friend he met at Parris Island. During the Battle of Huế, platoon leader Lieutenant Walter J. "Touchdown" Schinoski and a fellow Marine are killed by the NVA, who are eliminated soon after. Later, a booby trap kills the squad leader, Sergeant "Crazy Earl," leaving Cowboy in command. Becoming lost in the city, the squad is ambushed by a Viet Cong sniper who kills two members, "Eightball" and "Doc Jay." As the squad approaches the sniper's location, Cowboy is killed.

Assuming command, squad machine gunner "Animal Mother" leads an attack on the sniper. Joker locates her first, but his M16 rifle jams, alerting the sniper to his presence. As the sniper opens fire, she is revealed to be a teenage girl. Rafterman shoots and mortally wounds her. As the squad converges on the sniper, she begs for death, leading to an argument over whether to kill her or leave her to die in pain. Animal Mother agrees to a mercy killing but only if Joker will handle it, and after some hesitation, Joker shoots her. Later, as night falls, the Marines march to the Perfume River singing the "Mickey Mouse March". A narration of Joker's thoughts conveys that, despite being "in a world of shit", he is glad to be alive and no longer afraid.

Cast

edit- Matthew Modine as Private (later Sergeant) J. T. "Joker" Davis, a wisecracking young Marine. On set, Modine kept a diary that in 2005 was adapted into a book and in 2013 into an interactive app.[9]

- Adam Baldwin as Sergeant "Animal Mother," a combat-hungry machine gunner who takes pride in killing enemy soldiers, and scorns any authority other than his own. Arnold Schwarzenegger was first considered for the role but turned it down in favor of a part in The Running Man.[10]

- Vincent D'Onofrio as Private Leonard "Gomer Pyle"[a] Lawrence, an overweight, slow-minded recruit who is the subject of Hartman's mockery. D'Onofrio heard from Modine of the auditions for the film. D'Onofrio recorded his audition using a rented video camera and was dressed in army fatigues. According to Kubrick, Pyle was "the hardest part to cast in the whole movie"; Modine suggested D'Onofrio to Kubrick, so he cast him in the part.[12][13] D'Onofrio was required to gain 70 pounds (32 kg).[14][15]

- R. Lee Ermey (credited as "Lee Ermey") as Gunnery Sergeant L. Hartman, a harsh, foul-mouthed and ruthless senior drill instructor. Ermey used his actual experience as a U.S. Marines drill instructor in the Vietnam War to improvise much of his dialogue.[16][17]

- Dorian Harewood as Corporal "Eightball," a member of the squad and Animal Mother's friend.

- Arliss Howard as Private (later Sergeant) "Cowboy" Evans, a friend of Joker and a member of the Lusthog Squad.

- Kevyn Major Howard as Private First Class "Rafterman," a combat photographer.

- Ed O'Ross as First Lieutenant Walter J. "Touchdown" Schinoski, the Lusthog Squad's platoon leader.

- John Terry as First Lieutenant Lockhart, the editor of Stars and Stripes.

- Kieron Jecchinis as Sergeant "Crazy Earl," the first Lusthog Squad leader.

- Bruce Boa as the Colonel who scolds Joker for wearing a peace symbol on his lapel.

- Kirk Taylor as Private "Payback"

- John Stafford as "Doc Jay," a Navy hospital corpsman providing medical support for the squad.

- Tim Colceri as a ruthless and sadistic helicopter door gunner who suggests that Joker and Rafterman write a story about him. Colceri, a former Marine, was originally slated to play Hartman, a role that went to Ermey. Kubrick gave Colceri this smaller part as a consolation.[18]

- Ian Tyler as Lieutenant Cleves, an officer present at the uncovering of a mass grave.

- Gary Landon Mills as Donlon, a squad member who works as a radio operator.

- Sal Lopez as "T.H.E. Rock"

- Papillon Soo Soo as a Da Nang prostitute

- Ngoc Le as the Viet Cong sniper

- Peter Edmund as Private "Snowball" Brown, a recruit in Hartman's platoon.

Themes

editMichael Pursell's essay "Full Metal Jacket: The Unravelling of Patriarchy" (1988) was an early, in-depth consideration of the film's two-part structure and its criticism of masculinity. Pursell wrote that the film shows "war and pornography as facets of the same system".[19]

Many reviewers praised the military brainwashing themes in the boot-camp portion of the film while viewing the film's second half as more confusing and disjointed. Rita Kempley of The Washington Post wrote, "it's as if they borrowed bits of every war movie to make this eclectic finale."[20] Roger Ebert saw the film as an attempt to tell a story of individual characters and the war's effects on them. According to Ebert, the result is a shapeless film that feels "more like a book of short stories than a novel".[21] Julian Rice, in his book Kubrick's Hope (2008), saw the second part of the film as a continuation of Joker's psychic journey in his attempt to understand human evil.[22]

Tony Lucia, in his 1987 review of Full Metal Jacket for the Reading Eagle, examined the themes of Kubrick's career, suggesting "the unifying element may be the ordinary man dwarfed by situations too vast and imposing to handle". Lucia refers to the "military mentality" in this film and also said the theme covers "a man testing himself against his own limitations", and concluded: "Full Metal Jacket is the latest chapter in an ongoing movie which is not merely a comment on our time or a time past, but on something that reaches beyond."[23]

British critic Gilbert Adair wrote, "Kubrick's approach to language has always been reductive and uncompromisingly deterministic in nature. He appears to view it as the exclusive product of environmental conditioning, only very marginally influenced by concepts of subjectivity and interiority, by all the whims, shades and modulations of personal expression."[24]

Michael Herr wrote of his work on the screenplay, "The substance was single-minded, the old and always serious problem of how you put into a film or a book the living, behaving presence of what Jung called the shadow, the most accessible of archetypes, and the easiest to experience ... War is the ultimate field of Shadow-activity, where all of its other activities lead you. As they expressed it in Vietnam, 'Yea, though I walk through the Valley of the Shadow of Death, I will fear no Evil, for I am the Evil'."[25]

Production

editDevelopment

editIn early 1980, Kubrick contacted Michael Herr, author of the Vietnam War memoir Dispatches (1977), to discuss work on a film about the Holocaust but Kubrick discarded that idea in favor of a film about the Vietnam War.[26] Herr and Kubrick met in England; Kubrick told Herr he wanted to make a war film but had yet to find a story to adapt.[12] Kubrick discovered Gustav Hasford's novel The Short-Timers (1979) while reading the Kirkus Review.[27] Herr received the novel in bound galleys and thought it a masterpiece.[12] In 1982, Kubrick read the novel twice; he concluded it is "a unique, absolutely wonderful book" and decided to adapt it for his next film.[27] According to Kubrick, he was drawn to the book's dialogue, which he found "almost poetic in its carved-out, stark quality".[27] In 1983, Kubrick began researching for the film; he watched archival footage and documentaries, read Vietnamese newspapers on microfilm from the Library of Congress, and studied hundreds of photographs from the era.[28] Initially, Herr was not interested in revisiting his Vietnam War experiences, but Kubrick spent three years persuading him, describing the discussions as "a single phone call lasting three years, with interruptions".[26]

In 1985, Kubrick contacted Hasford and invited him to join the team;[12] they spoke by telephone three to four times a week for hours at a time.[29] Kubrick had already written a detailed treatment of the novel,[12] and they met at Kubrick's home every day, breaking the treatment into scenes. Herr then wrote the first draft of the film script.[12] Kubrick worried the audience might misread the book's title as a reference to people who did only half a day's work and changed it to Full Metal Jacket after coming across the phrase in a gun catalogue.[12] After the first draft was complete, Kubrick telephoned his orders to Hasford and Herr, who mailed their submissions to him.[30] Kubrick read and edited Hasford's and Herr's submissions, and the team repeated the process. Neither Hasford nor Herr knew how much each had contributed to the screenplay, which led to a dispute over the final credits.[30] Hasford said: "We were like guys on an assembly line in the car factory. I was putting on one widget and Michael was putting on another widget and Stanley was the only one who knew that this was going to end up being a car."[30] Herr said Kubrick was not interested in making an anti-war film but "he wanted to show what war is like".[26]

At some point, Kubrick wanted to meet Hasford in person, but Herr advised against this, describing The Short-Timers author as a "scary man, a big, haunted marine", and did not believe Hasford and Kubrick would "get on".[26] Kubrick, however, insisted on the meeting, which occurred at Kubrick's house in England. The meeting went poorly; Kubrick privately told Herr: "I can't deal with this man," and Hasford did not meet with Kubrick again.[26]

Casting

editThrough Warner Bros., Kubrick advertised a casting search in the United States and Canada. He used videotape to audition actors and received over 3,000 submissions. Kubrick's staff screened the tapes, leaving 800 of them for him to review.[12]: 461

Former U.S. Marines drill instructor Lee Ermey was originally hired as a technical advisor. Ermey asked Kubrick if he could audition for the role of Hartman. Kubrick, who had seen Ermey's portrayal of drill instructor Staff Sergeant Loyce in The Boys in Company C (1978), told Ermey that he was not vicious enough to play the character. Ermey improvised insulting dialogue against a group of Royal Marines who were being considered for the part of background Marines in order to demonstrate his ability to play the character and to show how a drill instructor attacks individuality in new recruits.[12]: 462 Upon viewing the videotape of these sessions, Kubrick offered Ermey the role, realizing he "was a genius for this part".[28] Kubrick incorporated the 250-page transcript of Ermey's rants into the script.[12]: 462–463 Ermey's experience as a drill instructor during the Vietnam War proved invaluable; Kubrick estimated that Ermey wrote 50% of his character's dialogue, particularly the insults.[31]

While Ermey practiced his lines in a rehearsal room, Kubrick's assistant Leon Vitali would throw tennis balls and oranges at him, which Ermey had to catch and throw back as quickly as possible while saying his lines as fast as he could. Any hesitation, slowdown, slip or missed line would necessitate restarting, and 20 error-free runs were required. "[He] was my drill instructor," Ermey said of Vitali.[12]: 463 [32]

Nine months of negotiations to cast Anthony Michael Hall as Private Joker were unsuccessful; Hall would later regret not doing the film.[33][34][35] Val Kilmer was also considered for the role, and Bruce Willis declined a role because of commitments to his television series Moonlighting.[36] Kubrick offered Ed Harris the role of Hartman but Harris declined it, a decision that he later called "foolish".[37] Robert De Niro was also considered for the role, although Kubrick eventually felt that the audience would "feel cheated" if De Niro's character were killed in the first hour.[38] Bill McKinney was also considered for the part, but Kubrick professed an irrational fear of the actor. McKinney was known for his role as a rural psychopath in 1972's Deliverance, most memorably in a sequence that Kubrick described as "the most terrifying scene ever put on film". McKinney was about to fly from Los Angeles to London to audition for Kubrick and the producers when he received a message at the airport informing him that his audition had been canceled. However, McKinney was paid in full.[39] Denzel Washington showed interest in the film but Kubrick did not send him a script.[40][41]

Filming

editPrincipal photography began on August 27, 1985, and concluded on August 8, 1986.[42][43] Scenes were filmed in Cambridgeshire, the Norfolk Broads, in eastern London at Millennium Mills and Beckton Gas Works in Newham and on the Isle of Dogs.[44] Kubrick hired Anton Furst as the production designer, impressed by his work on The Company of Wolves (1984).[45] Bassingbourn Barracks, a former Royal Air Force station and then a British Army base, was used as the Parris Island Marines boot camp.[28] A British army rifle range near Barton, Cambridge was used for the scene in which Hartman congratulates Private Pyle for his shooting skills. Kubrick and Furst worked from still photographs of Huế taken in 1968. Kubrick found an area owned by British Gas that closely resembled it and was scheduled to be demolished. The disused Beckton Gas Works, a few miles from central London, was filmed to depict Huế after attacks.[31][46][45] Kubrick had buildings demolished and the film's art director used a wrecking ball to knock holes in some of the buildings over the course of two months.[31] Kubrick had a plastic replica jungle delivered from California, but once he saw it, he dismissed the idea, saying; "I don't like it. Get rid of it."[47] The open country scenes were filmed at marshland in Cliffe-at-Hoo[48] and along the River Thames. Locations were decorated with 200 palm trees imported from Spain[27] and 100,000 plastic tropical plants from Hong Kong.[31]

Kubrick acquired four M41 tanks from a Belgian army colonel who was an admirer of his work.[49] Westland Wessex helicopters, which have a much longer and less-rounded nose than that of the Vietnam era H-34, were painted Marines green to represent Sikorsky H-34 Choctaw helicopters. Kubrick obtained a selection of rifles, M79 grenade launchers and M60 machine guns from a licensed weapons dealer.[28]

Modine described the filming as difficult. Beckton Gas Works was a toxic environment for the film crew, being contaminated with asbestos and hundreds of other chemicals.[50] During the boot camp sequence of the film, Modine and the other recruits underwent Marine Corps training, during which Ermey yelled at them for 10 hours a day while filming the Parris Island scenes. To ensure that the actors' reactions to Ermey's lines were as authentic and fresh as possible, Ermey and the recruits did not rehearse together.[12]: 468 For film continuity, each recruit had his head shaved once a week.[51]

Modine fought with Kubrick about whether he could leave the set to be with his pregnant wife in the delivery room. Modine threatened to cut himself and get sent to the hospital himself to force Kubrick to relent.[52] He also nearly fought with D'Onofrio during filming the boot camp scenes after he taunted D'Onofrio while laughing with the film's extras between takes.[53]

During filming, Ermey was injured in a car crash and broke several ribs, leaving him unavailable for four and a half months.[31][54]

During Cowboy's death scene, a building that resembles the alien monolith in Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968) is visible. Kubrick described this as an "extraordinary accident".[31]

During filming, Hasford contemplated legal action over the writing credits. Originally, the filmmakers intended Hasford to receive an "additional dialogue" credit, but he fought for and eventually received full credit.[30] Hasford and two friends visited the set dressed as extras but was mistaken by a crew member for Herr. Hasford identified himself as the writer of the source material.[29]

Kubrick's daughter Vivian, who appears uncredited as a news camera operator, shadowed the filming of Full Metal Jacket. She filmed 18 hours of behind-the-scenes footage for a potential "making-of" documentary that went unmade. Sections of her work can be seen in the documentary Stanley Kubrick's Boxes (2008).[55][56]

Music

editVivian Kubrick, under the alias Abigail Mead, wrote the film's score. According to an interview in the January 1988 issue of Keyboard, the film was scored mostly with a Series III edition Fairlight CMI synthesizer and a Synclavier. For the period music, Kubrick reviewed Billboard's list of the top 100 hits for each year from 1962 to 1968, considering many songs but finding that "sometimes the dynamic range of the music was too great, and we couldn't work in dialogue."[31]

A single titled "Full Metal Jacket (I Wanna Be Your Drill Instructor)," credited to Mead and Nigel Goulding, was released to promote the film and incorporates Ermey's drill cadences from the film. The single reached #1 in Ireland, #2 in the UK,[57] #4 in both the Netherlands and the Flanders region of Belgium, #8 in West Germany, #11 in Sweden and #29 in New Zealand.

Release

editBox office

editFull Metal Jacket received a limited release on June 26, 1987, in 215 theaters.[4] During its opening weekend, it accrued $2.2 million, an average of $10,313 per theater, ranking it the number 10 film for the weekend June 26–28.[4] It took a further $2 million for a total of $5.7 million before being widely released in 881 theaters on July 10, 1987.[4] The weekend of July 10–12 saw the film gross $6.1 million, an average of $6,901 per theater, and rank as the second-highest-grossing film. Over the next four weeks the film opened in a further 194 theaters to its widest release of 1,075 theaters; it closed two weeks later with a total gross of $46.4 million, making it the twenty-third-highest-grossing film of 1987.[4][58] As of 1998[update], the film had grossed $120 million worldwide.[5]

Home media

editThe home media release history of Full Metal Jacket is summarized in the following table. Minor cuts to the 1h 57m theatrical version were made to comply with the censor boards overseeing the various territories in which the film was released. For technical reasons the PAL mastering standard speeds up playback by around 4% compared with NTSC, leading to slightly shorter runtimes (around 1h 52m) in releases mastered for territories other than the US and Japan.[59]

| Territory | Title | Released | Publisher | Aspect Ratio | Cut | Runtime | Commentaries | Mix | Resolution | Master | Medium |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| USA | #3000082901[60] | September 22, 2020[60] | Warner Home Video | 1.78:1 | Theatrical | 1h 56m | none | 5.1, mono (192 kbit/s) | 2160p | 4K | Blu-ray |

| #3000082360[61] | September 22, 2020[61] | 5.1 | |||||||||

| #3000083363[62] | September 22, 2020[62] | 1080p | |||||||||

| UK | September 22, 2020[63] | 2160p | |||||||||

| USA | #118627 | May 7, 2013[64] | 1.85:1[64] | 1080p | 2K | ||||||

| October 16, 2012 | 1.78:1 | 480i | DVD | ||||||||

| #201341 | October 16, 2012[65] | 1.78:1[65] | 1080p | Blu-ray | |||||||

| #400002309 | August 7, 2012[66] | 1.78:1 | 1h 57m[67] | ||||||||

| #5000099235[68] | May 23, 2011[69] | 1h 52m | |||||||||

| #80931 | October 28, 2007 | 1.78:1[70] | HD-DVD | ||||||||

| #118627 | October 23, 2007[71] | 1.78:1[72] | 1h 56m[73] | Blu-ray | |||||||

| #116116 | 2007 | 1.85:1[74] | 1h 57m | 480i | DVD | ||||||

| UK | #Z1 80931[75] | 1.78:1 | 1080p | HD-DVD | |||||||

| #Z1 Y18626[76] | 2007 | ||||||||||

| Germany | #Z1 Y18626[77] | 1h 57m | |||||||||

| USA | #116311 | May 15, 2007[78] | 1.33:1[78] | 1h 56m | 480i | DVD | |||||

| Sweden | #Z11 80931[79] | 1.78:1 | 1080p | HD-DVD | |||||||

| #Z11 Y18626[80] | 1h 57m | ||||||||||

| Norway | #Z12 Y18626[80] | 1h 57m | |||||||||

| Germany | #Z5 80931[81] | 1h 56m | |||||||||

| France | #Z7 80931 | 2006 | |||||||||

| USA | September 5, 2006[82] | 1.77:1[83] | 1h 57m[84] | 1080p[85] | Blu-ray | ||||||

| Japan | #WBHA-80931[86] | November 3, 2006 | 1.78:1 | 1h 57m | 1080p | HD-DVD | |||||

| USA | #11826[87] | May 16, 2006 | |||||||||

| November 6, 2001[88] | 1.33:1[88] | 480i | DVD | ||||||||

| June 12, 2001[89] | 1.85:1[89] | ||||||||||

| #21154 | 2001 | 1.33:1 | 1h 56m | mono | 240 lines | NTSC | VHS | ||||

| June 29, 2001[90] | mono[90] | 480i | DVD | ||||||||

| France | #1176013[91] | 1995 | mono | 425 lines | PAL | LaserDisc | |||||

| UK | #PES 11760 | 1993 | 240 lines | NTSC | VHS | ||||||

| USA | #11760[92] | 1991 | 1h 57m | 425 lines | LaserDisc | ||||||

| Finland | #WES 11760 | 1991 | Fazer Musiikki | 1h 52m | 576 lines | PAL | VHS | ||||

| USA | #11760 | 1990 | Warner Home Video | 1h 57m | 425 lines | NTSC | LaserDisc | ||||

| Japan | #NJL-11760 | July 25, 1989[93] | |||||||||

| #VHP47012 | 1989[94] | 1h 56m | 320 lines | VHD | |||||||

| USA | #11760 | 1988 | 240 lines | VHS | |||||||

| Japan | #NJV 11660 | 1987 | |||||||||

| Australia | #PEV 11760 | 1987 | 1h 55m | 576 lines | PAL | ||||||

| USA | 1987 | 240 lines | NTSC | VHS |

The 2020 4K UHD release uses a new HDR remastered native 2160p that was transferred from the original 35mm negative, which was supervised by Kubrick's personal assistant Leon Vitali. It contains the remixed audio and, for the first time since the original DVD release, the theatrical mono mix. The release was a critical success; publications praised its image and audio quality, calling the former exceptionally good and faithful to the original theatrical release, and Kubrick's vision while noting the lack of new extras and bonus content.[95][96][97] A collector's edition box set of this 4K UHD version was released with different cover art, a replica theatrical poster of the film, a letter from director Stanley Kubrick, and a booklet about the film's production among other extras.[98]

Reception

editCritical reception

editReview aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes retrospectively collected reviews to give the film a score of 90% based on reviews from 84 critics and an average rating of 8.3/10. The summary states; "Intense, tightly constructed, and darkly comic at times, Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket may not boast the most original of themes, but it is exceedingly effective at communicating them."[99][100] Another aggregator, Metacritic, gave it a score of 76 out of 100 based on 19 reviews, which indicates a "generally favorable" response.[101] Reviewers generally reacted favorably to the cast—Ermey in particular—[102][103] and the film's first act about recruit training.[104][105] Several reviews, however, were critical of the latter part of the film, which is set in Vietnam, and what was considered a "muddled" moral message in the finale.[106][21]

Richard Corliss of Time called the film a "technical knockout", praising "the dialogue's wild, desperate wit; the daring in choosing a desultory skirmish to make a point about war's pointlessness," and "the fine, large performances of almost every actor", saying Ermey and D'Onofrio would receive Oscar nominations. Corliss appreciated "the Olympian elegance and precision of Kubrick's filmmaking."[102] Empire's Ian Nathan awarded the film three stars out of five, saying it is "inconsistent" and describing it as "both powerful and frustratingly unengaged". Nathan said after the opening act, which concerns the recruit training, the film becomes "bereft of purpose"; nevertheless, he summarized his review by calling it a "hardy Kubrickian effort that warms on you with repeated viewings" and praised Ermey's "staggering performance".[105] Vincent Canby of The New York Times called the film "harrowing, beautiful and characteristically eccentric". Canby echoed praise for Ermey, calling him "the film's stunning surprise ... he's so good—so obsessed—that you might think he wrote his own lines."[b] Canby said D'Onofrio's performance should be admired and described Modine as "one of the best, most adaptable young film actors of his generation", and concluded Full Metal Jacket is "a film of immense and very rare imagination".[107]

Jim Hall, writing for Film4 in 2010, awarded the film five stars out of five and added to the praise for Ermey, saying his "performance as the foul-mouthed Hartman is justly celebrated and it's difficult to imagine the film working anything like as effectively without him." The review preferred the opening training segment to the later Vietnam sequence, calling it "far more striking than the second and longer section". Hall commented the film ends abruptly but felt "it demonstrates just how clear and precise the director's vision could be when he resisted a fatal tendency for indulgence." Hall concluded; "Full Metal Jacket ranks with Dr. Strangelove as one of Kubrick's very best."[104] Jonathan Rosenbaum of the Chicago Reader called it "Elliptical, full of subtle inner rhymes ... and profoundly moving, this is the most tightly crafted Kubrick film since Dr. Strangelove, as well as the most horrific."[108] Variety called the film an "intense, schematic, superbly made" drama that is "loaded with vivid, outrageously vulgar military vernacular that contributes heavily to the film's power" but said it never develops "a particularly strong narrative". The cast performances were all labeled "exceptional"; Modine was singled out as "embodying both what it takes to survive in the war and a certain omniscience".[103] Gilbert Adair, writing about Full Metal Jacket, commented: "Kubrick's approach to language has always been of a reductive and uncompromisingly deterministic nature. He appears to view it as the exclusive product of environmental conditioning, only very marginally influenced by concepts of subjectivity and interiority, by all whims, shades and modulations of personal expression."[109]

Chicago Sun-Times critic Roger Ebert called Full Metal Jacket "strangely shapeless" and awarded it two and a half stars out of four. Ebert called it "one of the best-looking war movies ever made on sets and stage" but said this was not enough to compete with the "awesome reality of Platoon, Apocalypse Now and The Deer Hunter." Ebert criticized the film's Vietnam-set second act, saying the "movie disintegrates into a series of self-contained set pieces, none of them quite satisfying" and concluded the film's message is "too little and too late", having been done by other Vietnam war films. Ebert praised Ermey and D'Onofrio, saying: "These are the two best performances in the movie, which never recovers after they leave the scene."[21] Ebert's review angered Gene Siskel on their television show At The Movies; he criticized Ebert for liking Benji the Hunted more than Full Metal Jacket.[110] Time Out London disliked the film, saying: "Kubrick's direction is as steely cold and manipulative as the régime it depicts," and that the characters are underdeveloped, adding "we never really get to know, let alone care about, the hapless recruits on view".[106]

Audiences polled by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on an A+ to F scale.[111]

British television channel Channel 4 voted Full Metal Jacket fifth on its list of the greatest war films ever made.[112] In 2008, Empire placed the film at number 457 on its list of "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time."[113] In 2010, The Guardian ranked it 19th on its list of the "25 best action and war films of all time."[114] The film is ranked 95 on the American Film Institute's 100 Years... 100 Thrills list, which was published in 2001.[115]

Accolades

editBetween 1987 and 1989, Full Metal Jacket was nominated for eleven awards, including an Academy Award for Best Adapted Screenplay,[116][117] two BAFTA Awards for Best Sound and Best Special Effects,[118] and a Golden Globe for Best Supporting Actor for Ermey.[119] It won five awards, including three from overseas; Best Foreign Language Film from the Japanese Academy, Best Producer from the Academy of Italian Cinema,[120] Director of the Year at the London Critics Circle Film Awards and Best Director and Best Supporting Actor at the Boston Society of Film Critics Awards for Kubrick and Ermey respectively.[121] Of the five awards it won, four were awarded to Kubrick and the other was given to Ermey.

| Year | Award | Category | Recipient | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1987 | BAFTA Awards | Best Sound | Nigel Galt, Edward Tise and Andy Nelson | Nominated | [118] |

| Best Special Effects | John Evans | Nominated | [118] | ||

| 1988 | Academy Awards | Best Adapted Screenplay | Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr and Gustav Hasford | Nominated | [116][117] |

| Boston Society of Film Critics Awards | Best Director | Stanley Kubrick | Won | [121] | |

| Best Supporting Actor | R. Lee Ermey | Won | |||

| David di Donatello Awards | Best Producer – Foreign film | Stanley Kubrick | Won | [120] | |

| Golden Globes | Best Supporting Actor – Motion Picture | R. Lee Ermey | Nominated | [119] | |

| London Critics Circle Film Awards | Director of the Year | Stanley Kubrick | Won | ||

| Writers Guild of America | Best Adapted Screenplay | Stanley Kubrick, Michael Herr, Gustav Hasford | Nominated | ||

| 1989 | Kinema Junpo Awards | Best Foreign Language Film Director | Stanley Kubrick | Won | |

| Awards of the Japanese Academy | Best Foreign Language Film | Stanley Kubrick | Nominated |

Differences between novel and screenplay

editFilm scholar Greg Jenkins has analyzed the adaptation of the novel as a screenplay. The novel is in three parts and the film greatly expands the relatively brief first section about the boot camp on Parris Island and essentially discards Part III. This gives the film a twofold structure, telling two largely independent stories that are connected by the same characters. Jenkins said this structure is a development of concepts Kubrick originally discussed in the 1960s, when he talked about wanting to explode the usual conventions of narrative structure.[122]

Sergeant Hartman, who is renamed from the book's Gerheim, has an expanded role in the film. Private Pyle's incompetence is presented as weighing negatively on the rest of the platoon; unlike the novel, he is the only under-performing recruit.[123] The film omits Gerheim's disclosure that he thinks Pyle might be mentally unstable—a "Section 8"—to the other troops; instead, Joker questions Pyle's mental state. In contrast, Hartman praises Pyle, saying he is "born again hard". Jenkins says that portraying Hartman as having a warmer social relationship with the troops would have upset the balance of the film, which depends on the spectacle of ordinary soldiers coming to grips with Hartman as a force of nature who embodies a killer culture.[124]

Some scenes in the book were removed from the screenplay or conflated with others. For example, Cowboy's introduction of the "Lusthog Squad" was markedly shortened and supplemented with material from other sections of the book. Although the book's third section was largely omitted, elements from it were inserted into other parts of the film.[125] For instance, the climactic episode with the sniper is a conflation of two sections of Parts II and III of the book. According to Jenkins, the film presents this passage more dramatically but in less gruesome detail than the novel.

The film often has a more tragic tone than the book, which relies on callous humor. In the film, Joker remains a model of humane thinking, as evidenced by his moral struggle in the sniper scene and elsewhere. Joker works to overcome his own meekness rather than compete with other Marines. The film omits Joker's eventual domination over Animal Mother shown in the book.[126]

The film also omits Rafterman's death; according to Jenkins, this allows viewers to reflect on Rafterman's personal growth and speculate on his future growth after the war.[125]

In popular culture

editThe line "Me so horny. Me love you long time," which is uttered by the Da Nang street prostitute to Joker, became a catchphrase in popular culture[127][128] and was sampled by rap artists 2 Live Crew in their 1989 hit "Me So Horny" and by Sir Mix-A-Lot in "Baby Got Back" (1992).[129][130] Stand-up comic Margaret Cho used a similar quote in her solo show Notorious C.H.O. when describing how she felt as a child that her goal of one day working as a professional actress would be limited due to the lack of representation of Asian performers in popular culture, suggesting she considered she might someday play a sex worker in a film.

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ The "Gomer Pyle" nickname recalls the character from the Gomer Pyle, U.S.M.C. TV sitcom. He stands out from the other characters and is passively resistant to being stamped by Hartman into the Marine Corps mold.[11]

- ^ As noted above, much of Ermey's dialogue in the film was indeed based on his own improvisations.

References

edit- ^ "FULL METAL JACKET". British Board of Film Classification. Retrieved January 14, 2015.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". British Film Institute. Archived from the original on July 11, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog - Full Metal Jacket". American Film Institute. Archived from the original on August 29, 2019. Retrieved November 30, 2020.

- ^ a b c d e "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on December 23, 2011. Retrieved August 1, 2011.

- ^ a b "Kubrick Keeps 'em in Dark with 'Eyes Wide Shut'". Los Angeles Times. September 29, 1998. p. 2. Archived from the original on January 12, 2019. Retrieved April 20, 2020.

- ^ Dittmar, Linda; Michaud, Gene (1990). From Hanoi to Hollywood: The Vietnam War in American Film. Rutgers University Press. p. 31. ISBN 9780813515878.

- ^ "Awards Database Search". Archived from the original on February 8, 2009. Retrieved February 18, 2016.

- ^ "AFI'S 100 Most Thrilling American Films". afi.com. American Film Institute. Archived from the original on December 25, 2013. Retrieved August 19, 2016.

2001

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket Diary: A Q&A with Matthew Modine". Unframed. March 4, 2013. Archived from the original on September 1, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ Stice, Joel (July 31, 2014). "9 Famous Roles Almost Played By Arnold Schwarzenegger". Uproxx. Archived from the original on September 1, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ Abrams, J. (2007). The Philosophy of Stanley Kubrick. The Philosophy of Popular Culture. University Press of Kentucky. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-8131-7256-9. Retrieved February 4, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l LoBrutto, Vincent (1997). "Stanley Kubrick". Donald I. Fine Books.

- ^ Davids, Brian (September 25, 2020). "Matthew Modine Reflects on 'Full Metal Jacket' and the One Similarity Between Stanley Kubrick and Christopher Nolan". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ Bennetts, Leslie (July 10, 1987). "The Trauma of Being a Kubrick Marine". The New York Times. Archived from the original on February 8, 2011. Retrieved April 30, 2009.

- ^ Harrington, Amy (October 19, 2009). "Stars Who Lose and Gain Weight for Movie Roles". Fox News Channel. Archived from the original on April 11, 2015. Retrieved October 23, 2011.

- ^ Full Metal Jacket Additional Material. Blu-ray/DVD.

- ^ Andrews, Travis M. (April 17, 2018). "How R. Lee Ermey created his memorable Full Metal Jacket role". The Sydney Morning Herald. Archived from the original on April 28, 2018. Retrieved April 28, 2018.

- ^ Lyttelton, Oliver (August 7, 2012). "5 Things You Might Not Know About Stanley Kubrick's 'Full Metal Jacket'". Indie Wire. Archived from the original on September 1, 2018. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ Pursell, Michael (1988). "Full Metal Jacket: The Unravelling of Patriarchy". Literature/Film Quarterly. 16 (4): 324.

- ^ Kempley, Rita. Review Archived December 8, 2017, at the Wayback Machine, The Washington Post.

- ^ a b c Ebert, Roger (June 26, 1987). "Full Metal Jacket". rogerebert.com. Archived from the original on January 14, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- ^ Rice, Julian (2008). Kubrick's Hope: Discovering Optimism from 2001 to Eyes Wide Shut. Scarecrow Press.

- ^ Lucia, Tony (July 5, 1987). "'Full Metal Jacket' takes deadly aim at the war makers" (Review). Reading Eagle. Reading, Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2014.

- ^ Baxter 1997, p. 10.

- ^ Baxter 1997, p. 11.

- ^ a b c d e CVulliamy, Ed (July 16, 2000). "It Ain't Over Till It's Over". The Observer. Archived from the original on November 16, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Clines, Francis X (June 21, 1987). "Stanley Kubrick's Vietnam". The New York Times. Archived from the original on April 28, 2006. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ a b c d Rose, Lloyd (June 28, 1987). "Stanley Kubrick, At a Distance". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 4, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ a b Lewis, Grover (June 28, 1987). "The Several Battles of Gustav Hasford". Los Angeles Times Magazine. Archived from the original on October 19, 2015. Retrieved October 20, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Carlton, Bob. "Alabama Native wrote the book on Vietnam Film". The Birmingham News. Archived from the original on April 6, 2012. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ a b c d e f g Cahill, Tim (1987). "The Rolling Stone Interview". Rolling Stone. Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ Harmetz, Aljean (June 30, 1987). "'Jacket' Actor Invents His Dialogue". The New York Times.

- ^ Epstein, Dan. "Anthony Michael Hall from The Dead Zone – Interview". Underground Online. Archived from the original on November 8, 2009. Retrieved August 12, 2009.

- ^ "MOVIES : On the Rebound With Anthony Michael Hall". Los Angeles Times. April 3, 1988.

- ^ "Anthony Michael Hall's biggest regret is turning down Kubrick's 'Full Metal Jacket'". DNYUZ. June 13, 2024.

- ^ "Bruce Willis: Playboy Interview". Playboy. Playboy.com. Archived from the original on June 7, 2011. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ Sharf, Zack (May 2, 2018). "Ed Harris Rejected a Direct Offer From Stanley Kubrick, and He Knows 'It Was Foolish'". IndieWire. Retrieved July 13, 2022.

- ^ "Kubrick". Vanity Fair. April 21, 2010.

- ^ "Story of the Scene: 'Say it again, Bobby' and other greats". The Independent. September 24, 2009. Retrieved November 9, 2023.

- ^ "5 Things You Might Not Know About Stanley Kubrick's 'Full Metal Jacket'". August 7, 2012.

- ^ "Denzel Washington GQ October 2012 Cover Story". GQ. September 18, 2012.

- ^ Handore, Pratik (March 28, 2022). "Where Was Full Metal Jacket (1987) Filmed?". Cinemaholic. Retrieved May 16, 2023.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket (1987) - Misc Notes - TCM.com". March 6, 2016. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ "Movies, films TV locations in the UK Film and TV Set information, - Full Metal Jacket". www.information-britain.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 28, 2020. Retrieved January 1, 2021.

- ^ a b "Anton Furst". BOMB Magazine. April 1990. Archived from the original on November 3, 2017.

- ^ Wise, Damon (August 1, 2017). "How we made Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ Watson, Ian (2000). "Plumbing Stanley Kubrick". Playboy. Archived from the original on August 12, 2007. Retrieved October 11, 2007.

- ^ Kent Film Office. "Kent Film Office Full Metal Jacket Article". Archived from the original on September 26, 2015. Retrieved September 25, 2015.

- ^ Grove, Lloyd (June 28, 1987). "Stanley Kubrick, At a Distance". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 15, 2017. Retrieved November 3, 2017.

- ^ Modine; Full Metal Jacket Diary (2005)

- ^ Linfield, Susan (October 1987). "The Gospel According to Matthew". American Film. Archived from the original on 6 April 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2007.

- ^ Sokol, Tony (June 26, 2019). "Full Metal Jacket and Its Troubled Production". Den of Geek. Retrieved October 18, 2023.

- ^ "Matthew Modine interview: 'America has never dealt honestly with what its history is'". Independent.co.uk. February 22, 2021.

- ^ Sokol, Tony (June 26, 2019). "Full Metal Jacket and Its Troubled Production". Den of Geek.

- ^ "Stanley Kubrick's Boxes". Vimeo. 34:34-35:15, 35:21-38:36. Retrieved February 25, 2024.

- ^ Crow, Jonathan (February 20, 2014). "Behind-the-Scenes Footage of Stanley Kubrick's Full Metal Jacket". Retrieved June 24, 2024.

- ^ "Official singles Chart results matching:full metal jacket (i wanna be your drill instructor)". Official Charts Company. Archived from the original on May 11, 2016. Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket 1987". Box Office Mojo. Archived from the original on February 24, 2014. Retrieved October 25, 2011.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket Blu-ray - Matthew Modine". www.dvdbeaver.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Full Metal Jacket 4K Blu-ray (4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ a b Full Metal Jacket 4K Blu-ray (Best Buy Exclusive SteelBook), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ a b Full Metal Jacket Blu-ray (SteelBook), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ Medina, Victor (August 14, 2020). "Stanley Kubrick's 'Full Metal Jacket' Coming to 4K UHD". Cinelinx | Movies. Games. Geek Culture. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Full Metal Jacket Blu-ray (Wal-Mart Exclusive), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ a b Full Metal Jacket Blu-ray (Special Edition with Collectible Booklet & Senitype), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ Full Metal Jacket Blu-ray (DigiBook), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket: 25th Anniversary Edition (Digibook) Blu-ray Review | High Def Digest". bluray.highdefdigest.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ Stanley Kubrick: Visionary Filmmaker Collection Blu-ray (Lolita / 2001: A Space Odyssey / A Clockwork Orange / Barry Lyndon / The Shining / Full Metal Jacket / Eyes Wide Shut / Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures / O Lucky Malcolm), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ Stanley Kubrick: Visionary Filmmaker Collection Blu-ray (Lolita / 2001: A Space Odyssey / A Clockwork Orange / Barry Lyndon / The Shining / Full Metal Jacket / Eyes Wide Shut / Stanley Kubrick: A Life in Pictures / O Lucky Malcolm), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket: Deluxe Edition [80931]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "Blu-ray Release Dates, Blu-ray Release Calendar". www.blu-ray.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ Full Metal Jacket Blu-ray, retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket: Deluxe Edition Blu-ray Review | High Def Digest". bluray.highdefdigest.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ Full Metal Jacket DVD (Deluxe Widescreen Edition), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket [Z1 80931]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket [Z1 Y18626]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket [Z5 Y18626]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Full Metal Jacket DVD (Remastered / Stanley Kubrick Collection), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket [Z11 Y18626]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ a b "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket [Z12 Y18626]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket [Z5 80931]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket Blu-ray Review | High Def Digest". bluray.highdefdigest.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ Full Metal Jacket Blu-ray, retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket Blu-ray Review | High Def Digest". bluray.highdefdigest.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket Blu-ray Review | High Def Digest". bluray.highdefdigest.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket [WBHA-80931]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket: Remastered [118626]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ a b Full Metal Jacket DVD (Limited Edition Collector's Set), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ a b Full Metal Jacket DVD (Snap case), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ a b Full Metal Jacket DVD (Snap case), retrieved January 22, 2024

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket [1176013]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket [11760]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket [NJL-11760]". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "LaserDisc Database - Full Metal Jacket [VHP47012] on VHD Victor/JVC". www.lddb.com. Retrieved January 22, 2024.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket - 4K Ultra HD Blu-ray Ultra HD Review | High Def Digest". ultrahd.highdefdigest.com. Archived from the original on September 19, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ Harlow, Casimir (September 22, 2020). "Full Metal Jacket 4K Blu-ray Review". AVForums. Archived from the original on September 25, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ Full Metal Jacket 4K Blu-ray Release Date September 22, 2020, archived from the original on September 29, 2020, retrieved September 23, 2020

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket Ultimate Collector's Edition [1987] (4K Ultra HD + Blu-ray)". shop.warnerbros.co.uk. Archived from the original on September 20, 2020. Retrieved September 23, 2020.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". Rotten Tomatoes. October 20, 2011. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ "The Undeclared War Over Full Metal Jacket". The Daily Beast. RTST, INC. Archived from the original on April 1, 2010. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket". Metacritic. October 20, 2011. Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ a b Corliss, Richard (June 29, 1987). "Cinema: Welcome To Viet Nam, the Movie: II Full Metal Jacket". Time. Archived from the original on December 13, 2012. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ a b "Full Metal Jacket". Variety. December 31, 1986. Archived from the original on July 9, 2011. Retrieved July 7, 2011.

- ^ a b Hall, Jim (January 5, 2010). "Fast & Furious 5". Film4. Archived from the original on March 1, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ a b Nathan, Ian. "Full Metal Jacket". Empire. Archived from the original on February 26, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ a b "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". Time Out London. Archived from the original on October 12, 2011. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- ^ Canby, Vincent (June 26, 1987). "Kubrick's 'Full Metal Jacket,' on Vietnam". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 26, 2008. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ "Full Metal Jacket". Archived from the original on November 6, 2018. Retrieved April 20, 2020 – via www.metacritic.com.

- ^ Duncan 2003, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Scott, A. O. (June 25, 2015). "Review: In 'Max,' a Shellshocked Dog Reverts to His Heroic Self". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 20, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2017.

- ^ "Home". CinemaScore. Retrieved November 23, 2022.

- ^ "Channel 4's 100 Greatest War Movies of All Time". Archived from the original on August 12, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2011.

- ^ "The 500 Greatest Movies of All Time". Bauer Consumer Media. Archived from the original on January 19, 2012. Retrieved July 28, 2010.

- ^ Patterson, John (October 19, 2010). "Full Metal Jacket: No 19 best action and war film of all time". The Guardian. Retrieved July 12, 2021.

- ^ "AFI list of America's most heart-pounding movies" (PDF). American Film Institute. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ^ a b "The 60th Academy Awards (1988) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ a b "Full Metal Jacket (1987)". Movies & TV Dept. The New York Times. 2008. Archived from the original on February 27, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Film Nominations 1987". bafta.org. Archived from the original on September 22, 2011. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ a b "Awards Search". goldenglobes.org. Archived from the original on September 27, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ a b "David di Donatello Awards". daviddidonatello.it. Archived from the original on April 1, 2012. Retrieved October 16, 2011.

- ^ a b "BSFC Past Award Winners". BSFC. Archived from the original on February 4, 2012. Retrieved July 13, 2014.

- ^ Jenkins 1997, p. 128.

- ^ Jenkins 1997, p. 123.

- ^ Jenkins 1997, p. 124.

- ^ a b Jenkins 1997, p. 146.

- ^ Jenkins 1997, p. 147.

- ^ Vineyard, Jennifer (July 30, 2008). "Mariah Carey, Fergie Promise To 'Love You Long Time' – But Is The Phrase Empowering Or Insensitive?". MTV News. Archived from the original on March 10, 2019.

- ^ Powers, Ann (December 8, 2010). "Love is lost on this phrase". Chicago Tribune. p. 66. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Knopper, Steve (March 14, 2003). "The Crew still has plenty of life left". Chicago Tribune. p. 8. Archived from the original on May 5, 2021. Retrieved April 3, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ McGowan, Kelly (July 19, 2017). "A restaurant named Me So Hungry: tasteless?". USA Today. Archived from the original on July 31, 2017.

Bibliography

edit- Baxter, John (1997). Stanley Kubrick: A Biography. Harper. ISBN 978-0-00-638445-8.

- Duncan, Paul (2003). Stanley Kubrick: The Complete Films. Taschen GmbH. ISBN 978-3836527750.

- Jenkins, Greg (1997). Stanley Kubrick and the Art of Adaptation: Three Novels, Three Films. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-3097-0.

- Kubrick, S.; Herr, M.; Hasford, G. (1987). Full Metal Jacket: The Screenplay. Borzoi book. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-394-75823-7.

- Kubrick, Stanley (1987). Full Metal Jacket. Knopf. ISBN 978-0394758237.

- Modine, Matthew (2005). Full Metal Jacket Diary. Rugged Land. ISBN 978-1590710470.