The Standard Alphabet is a Latin-script alphabet developed by Karl Richard Lepsius. Lepsius initially used it to transcribe Egyptian hieroglyphs in his Denkmäler aus Ägypten und Äthiopien[1] and extended it to write African languages, published in 1853,[citation needed] 1854[2] and 1855,[3] and in a revised edition in 1863.[4] The alphabet was comprehensive but was not used much as it contained a lot of diacritic marks and was difficult to read and typeset at that time. It was, however, influential in later projects such as Ellis's Paleotype, and diacritics such as the acute accent for palatalization, under-dot for retroflex, underline for Arabic emphatics, and the click letters continue in modern use.

| Lepsius Standard Alphabet | |

|---|---|

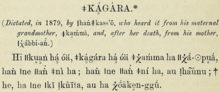

First line of [[ǂKá̦gára|ǂKá̦gára]] in ǀXam language in W.H.I. Bleek and L. Lloyd, Specimens of Bushman folklore, 1911 | |

| Script type | alphabet

|

| Creator | Karl Richard Lepsius |

| Published | 1849

|

Time period | late 19th century |

| Languages | Egyptian language, languages of Africa |

| Related scripts | |

Parent systems | |

Child systems | Paleotype |

Vowels

editVowel length is indicated by a macron (ā) or a breve (ă) for long and short vowels, respectively. Open vowels are marked by a line under the letter (e̱), while a dot below the letter makes it a close vowel (ẹ). Rounded front vowels are written with an umlaut (ö [ø] and ü [y]), either on top or below, when the space above the letter is needed for vowel length marks (thus ṳ̄ or ṳ̆). Unrounded back vowels are indicated by a 'hook' (ogonek) on ę or į. Central vowels may be written as one of these series, or as reduced vowels.

As in the International Phonetic Alphabet, nasal vowels get a tilde (ã).

A small circle below a letter is used to mark both the schwa (e̥, also ḁ etc. for other reduced vowels) and syllabic consonants (r̥ or l̥, for instance).

Diphthongs do not receive any special marking, they are simply juxtaposed (ai [ai̯]). A short sign can be used to distinguish which element of the diphthong is the on- or off-glide (uĭ, ŭi) Vowels in hiatus can be indicated with a diaeresis when necessary (aï [a.i]).

Other vowels are a with a subscript e for [æ]; a with a subscript o for [ɒ], and o̩ for [ʌ] or maybe [ɐ]. The English syllabic [ɝ] is ṙ̥.

Word stress is marked with an acute accent on a long vowel (á) and with a grave accent on a short vowel (à).

Klemp (p. 56*-58*) interprets the values of Lepsius's vowels as follows:

| a [a ~ ɑ] |

| ą [æ] o̗ [ʌ] ḁ [ɒ] |

| e̠ [ɛ] o̤̠ [œ] o̠ [ɔ] |

| e [e̞] ę [ɜ] o̤ [ø̞] o [o̞] |

| ẹ [e] o̤̣ [ø] ọ [o] |

| i [i] į [ɨ ~ ɯ] ṳ [y] u [u] |

Consonants

editThe Lepsius letters without predictable diacritics are as follows:

Other consonant sounds may be derived from these. For example, palatal and palatalized consonants are marked with an acute accent: ḱ [c], ǵ [ɟ], ń [ɲ], χ́ [ç], š́ [ɕ], γ́ [ʝ], ž́ [ʑ], ĺ [ʎ], ‘ĺ [ʎ̝̊], ı́ [ǂ], ṕ [pʲ], etc. These can also be written ky, py etc.

Labialized velars are written with an over-dot: ġ [ɡʷ], n̈ [ŋʷ], etc. (A dot on a non-velar letter, as in ṅ and ṙ in the table above, indicates a guttural articulation.)

Retroflex consonants are marked with an under-dot: ṭ [ʈ], ḍ [ɖ], ṇ [ɳ], ṣ̌ [ʂ], ẓ̌ [ʐ], ṛ [ɽ], ḷ [ɭ], and ı̣ [ǃ].

The Semitic "emphatic" consonants are marked with an underline: ṯ [tˤ], ḏ [dˤ], s̱ [sˤ], ẕ [zˤ], δ̱ [ðˤ], ḻ [lˤ].

Aspiration is typically marked by h: kh [kʰ], but a turned apostrophe (Greek spiritus asper) is also used: k̒ [kʰ], ģ [ɡʱ]. Either convention may be used for voiceless sonorants: m̒ [m̥], ‘l [ɬ].[7]

Affricates are generally written as sequences, e.g. tš for [t͡ʃ]. But the single letters č [t͡ʃ], ǰ [d͡ʒ], c̀ [t͡ɕ], j̀ [d͡ʑ], ț [t͡s], and d̦ [d͡z] are also used.

Implosives are written with a macron: b̄ [ɓ], d̄ [ɗ], j̄ [ʄ], ḡ [ɠ]. As with vowels, long (geminate) consonants may also be written with a macron, so this transcription can be ambiguous.

Lepsius typically characterized ejective consonants as tenuis, as they are completely unaspirated, and wrote them with the Greek spiritus lenis (p’, t’, etc.), which may be the source of the modern convention for ejectives in the IPA. However, when his sources made it clear that there was some activity in the throat, he transcribed them as emphatics.

When transcribing consonant letters which are pronounced the same but are etymologically distinct, as in Armenian, diacritics from the original alphabet or roman transliteration may be carried over. Similarly, unique sounds such as Czech ř may be carried over into Lepsius transcription. Lepsius used a diacritic r under t᷊ and d᷊ for some poorly described sounds in Dravidian languages.

Standard capitalization is used. For example, when written in all caps, γ becomes Γ (as in AFΓAN "Afghan").

Tones

editTones are marked with an acute and grave accents (backticks) to the right and near the top or the bottom of the corresponding vowel. The diacritic may be underlined for a lower pitch, distinguishing in all eight possible tones.

Tone is not written directly, but rather needs to be established separately for each language. For example, the acute accent may indicate a high tone, a rising tone, or, in the case of Chinese, any tone called "rising" (上) for historical reasons.

| S.A. | Level value | Contour value |

|---|---|---|

| ma´ [8] | [má] | [mǎ] |

| ma | [mā] | |

| ma` | [mà] | [mâ] |

Low rising and falling tones can be distinguished from high rising and falling tones by underlining the accent mark: ⟨ma´̠, ma`̠⟩. The underline also transcribes the Chinese yin tones, under the mistaken impression that these tones are actually lower. Two additional tone marks, without any defined phonetic value, are used for Chinese: "level" maˏ (平) and checked maˎ (入); these may also be underlined.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Lepsius 1849

- ^ Lepsius 1854

- ^ Lepsius 1855

- ^ Lepsius 1863

- ^ Lepsius used j for Slavic languages, y for most others.

- ^ The four click letters are based on a vertical pipe without ascender or descender (that is, the height of the letter n). In some fonts, such as that used for Krönlein's Khoekhoe grammar, they have the height of the letter t.

- ^ With the apostrophe placed before the l, presumably to avoid stacking it too high to print

- ^ In Lepsius's publications, this looks like a vertical bar ⟨ˈ⟩. However, it is repeatedly called "acute" in the text.

- Lepsius, C. R. 1849. Denkmäler aus Ägypten un Äthiopien. Full text at Münchener DigitalisierungsZentrum (MDZ).

- Lepsius, C. R. 1854. Das allgemeine linguistische Alphabet: Grundsätze der Übertragung fremder Schriftsysteme und bisher noch ungeschriebener Sprachen in europäische Buchstaben. Berlin: Verlag von Wilhelm Hertz Full text available on Google Books.

- Lepsius, C. R. 1855. Das allgemeine linguistische Alphabet: Grundsätze der Übertragung fremder Schriftsysteme und bisher noch ungeschriebener Sprachen in europäische Buchstaben. Berlin: Verlag von Wilhelm Hertz. Full text available on Internet Archive.

- Lepsius, C. R. 1863. Standard Alphabet for Reducing Unwritten Languages and Foreign Graphic Systems to a Uniform Orthography in European Letters, 2nd rev. edn. Williams & Norgate, London. Full text available on Google Books. Full text available on Internet Archive.

- Lepsius, C. R. 1863. Standard Alphabet for Reducing Unwritten Languages and Foreign Graphic Systems to a Uniform Orthography in European Letters, 2nd rev. edn. London 1863, modern reprint with introduction by J. Alan Kemp, John Benjamins Publishing, Amsterdam 1981. Preview available on Google Books.

- Faulmann, Carl 1880. Das Buch der Schrift enthaltend die Schriftzeichen und Alphabete aller Zeiten und aller Völker des Erdkreises, 2nd rev. edn. Kaiserlich-königliche Hof- und Staatsdruckerei, Wien. Full text available on Internet Archive.

- Köhler, O., Ladefoged, P., J. Snyman, Traill, A., R. Vossen: The Symbols for Clicks.