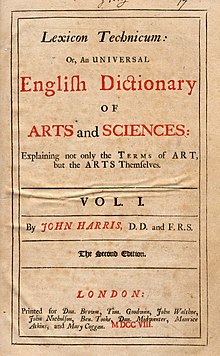

Lexicon Technicum: or, An Universal English Dictionary of Arts and Sciences: Explaining not only the Terms of Art, but the Arts Themselves was in many respects the first alphabetical encyclopedia written in English, compiled by John Harris, with the first volume published in 1704 and the second in 1710.[1] Although the emphasis of the Lexicon Technicum was on mathematical subjects, its contents go beyond what would be called science or technology today, in conformity with the broad eighteenth century understanding of the terms "arts" and "science," and it includes entries on the humanities and fine arts, notably on law, commerce, music, and heraldry. However, the Lexicon Technicum neglects theology, antiquity, biography, and poetry.

Overview

editThe Lexicon Technicum was the work of a London clergyman, John Harris (1666-1719). Its professed advantage over French dictionaries of the arts and sciences was that it contained explanation not only of the terms used in the arts and sciences, but also of the arts and sciences themselves. Harris issued a three-page proposal for this work in 1702, and the first edition of the first volume was published in London in 1704. The first volume contains 1220 pages, 4 plates, and many additional diagrams and figures within the text. Like many early English encyclopedias, the pages are not numbered; numbering may have been thought unnecessary as readers could search by its alphabetical arrangement.

Volume 2, which was also alphabetized from A through Z, was first published in 1710. The second volume contains 1419 pages and 4 plates, with a list of about 1300 subscribers. A previously unpublished treatise on acids by Sir Isaac Newton was included in its original Latin[2] along with Harris's English translation,[3] perhaps without the latter's permission or encouragement.[4] A large part of the volume consists of mathematical and astronomical tables, since Harris intended his work to serve as a small mathematical library. He provided tables of logarithms, sines, tangents, and secants, a two-page list of books, and an index of the articles in both volumes under 26 heads, filling 50 pages. The longest lists are for law (1700 articles), surgery, anatomy, geometry, fortification, botany, and music.

In his preface, Harris stated that he got less help from previous dictionaries than one would expect. While acknowledging some borrowing, Harris insisted that "much the greater part of what [the reader] will find here is collected from no Dictionaries, but from the best Original Authors I could procure." Harris's preface touted his coverage of mathematical subjects. He admitted the imperfection of his data on stars, noting that Flamsteed had refused to assist him, but he vaunted his coverage of astronomy, especially his full coverage of Newton's theories of the moon and of comets. In botany he claimed to have given "a pretty exact botanick lexicon, which was what we really wanted before," using Dr John Ray's method. To describe the parts of a ship accurately, he supposedly "often" went on board himself. In law, he wrote, he abridged from the best writers and had the result "carefully examined and corrected by a Gentleman of known Ability in that Profession."

The specified aims of the book did not prevent Harris from including some highly opinionated asides, for example this definition conveying the poor view he took of lawyers: "Sollicitor, is a Man imploy'd to take care of, and follow Suits depending in Courts of Law, or Equity, formerly allowed only to Nobility, whose Menial Servants they were; but now too frequently used by others, to the damage of the People, and the increase of Champerty and Maintenance".

Harris wrote that he had wished to supply an index for each art and science as well as more plates on anatomy and ships, but the underwriters could not afford it, "the Book having swelled so very much beyond the Expectation."

A review of this work, extending to the unusual length of four pages, appeared in the Philosophical Transactions for 1704.[5]

The Lexicon Technicum was long very popular, enduring through at least 1744 as the main rival of Ephraim Chambers's Cyclopaedia. The final publication of the two volumes of the Lexicum Technicum was in 1736. An anonymous one-volume supplement did appear in 1744, with 996 pages and 6 plates, but this work was allegedly "not well received," being perceived by contemporaries as a mere "booksellers speculation."[6] In any case, no new editions of the Lexicon Technicum were published thereafter.

Publication History

editUnlike most multi-volume works, the several editions of volumes 1 and 2 were not synchronized until 1736. The first volume appeared in five editions, while the second volume appeared only in three editions. The first edition of volume 1 appeared in 1704; the second edition in 1708, the third edition in 1716, and the fourth edition in 1725. In contrast, the first edition of volume 2 appeared in 1710, and the second edition did not appear until 1723. The two volumes were not published together until 1736, constituting the fifth edition of the first volume and the third edition of the second volume. The supplement of 1744 was billed as volume 3.

We do not know the names of the editors who carried on Harris's work after his death in 1719.

Notes

edit- ^ Robert Collison, Encyclopaedias: Their History throughout the Ages (New York: Hafner, 1966), p. 99.

- ^ "De Natura acidorum" (1692)

- ^ "Some Thoughts about the Nature of Acids; by Sir Isaac Newton"

- ^ Lael Ely Bradshaw, “John Harris’s Lexicon Technicum,” in Notable Encyclopedias of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: Nine Predecessors of the Encyclopédie, ed. Frank A. Kafker (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1981), p.110.

- ^ Harris, J. (July 1704). "An Account of a Book: Lexicon Technicum; [...]". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London. 24 (292): 1699.

- ^ "Encyclopaedia," in Encyclopædia Britannica, 13th edition, vol. 19, p. 373.

References

edit- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Encyclopaedia". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 369–382. (See p. 373.)

- Bradshaw, Lael Ely, “John Harris’s Lexicon technicum,” in Notable Encyclopedias of the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries: Nine Predecessors of the Encyclopédie, ed. Frank A. Kafker (Oxford: Voltaire Foundation, 1981), pp. 107–21.

- Collison, Robert, Encyclopaedias: Their History throughout the Ages (New York: Hafner, 1966).

External links

edit- Sample page from the 1708 edition

- Lexicon technicum, or, An universal English dictionary of arts and sciences : explaining not only the terms of art, but the arts themselves Vol. 1 (2nd ed)

- Lexicon technicum, or, An universal English dictionary of arts and sciences : explaining not only the terms of art, but the arts themselves Vol. 2 (2nd ed)