The Liancourt Rocks,[2] also known by their Korean name of Dokdo (Korean: 독도)[a] or their Japanese name of Takeshima,[b] are a group of islets in the Sea of Japan between the Korean peninsula and the Japanese archipelago administered by South Korea. The Liancourt Rocks comprise two main islets and 35 smaller rocks; the total surface area of the islets is 0.187554 square kilometres (46.346 acres) and the highest elevation of 168.5 metres (553 ft) is on the West Islet.[4][dead link] The Liancourt Rocks lie in rich fishing grounds that may contain large deposits of natural gas.[5] The English name Liancourt Rocks is derived from Le Liancourt,[c] the name of a French whaling ship that came close to being wrecked on the rocks in 1849.[6]

| Disputed islands | |

|---|---|

| |

The two main islets | |

| Other names | Liancourt Islets, Liancourt Islands, Takeshima, Dokdo, Tok Islets, Hornet Islands, Kajido, Sambongdo |

| Geography | |

| Location | Sea of Japan |

| Coordinates | 37°14′30″N 131°52′0″E / 37.24167°N 131.86667°E |

| Total islands | 91 (37 permanent land) |

| Major islands | East Islet, West Islet |

| Area | 18.745 ha (46.32 acres) East Islet: 7.33 hectares (18.1 acres) West Islet: 8.864 hectares (21.90 acres) |

| Highest elevation | 169 m (554 ft) |

| Highest point | West Islet |

| Administration | |

| County | Ulleung County, North Gyeongsang |

| Claimed by | |

| Town | Okinoshima, Shimane (Japan) |

| County | Ulleung County, North Gyeongsang |

| Demographics | |

| Population | Approximately 26[1] |

While South Korea controls the islets, its sovereignty over them is contested by Japan. North Korea also claims the territory. South Korea classifies the islets as Dokdo-ri, Ulleung-eup, Ulleung County, North Gyeongsang Province,[7] while Japan classifies the islands as part of Okinoshima, Oki District, Shimane Prefecture.

Geography

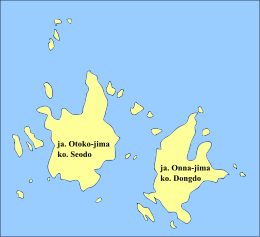

The Liancourt Rocks consist of two main islets and numerous surrounding rocks. The two main islets, called Seodo (서도; 西島; lit. western island) and Dongdo (동도; 東島; lit. eastern island) in Korean and Ojima (男島; "Male Island") and Mejima (女島; "Female Island") in Japanese, are 151 metres (495 ft) apart.[4] The Western Island is the larger of the two, with a wider base and higher peak, while the Eastern Island offers more usable surface area.

Altogether, there are about 90 islets and reefs,[4][dead link] volcanic rocks formed in the Cenozoic era, more specifically 4.6 to 2.5 million years ago. A total of 37 of these islets are recognized as permanent land.[verification needed]

The total area of the islets is about 187,554 square metres (46.346 acres), with their highest point at 168.5 metres (553 ft) on the West Islet.[4] The western islet is about 88,740 square metres (21.93 acres); the eastern islet is about 73,300 square metres (18.1 acres).[4] The western islet consists of a single peak and features many caves along the coastline. The cliffs of the eastern islet are about 10 to 20 metres (33 to 66 ft) high. There are two large caves giving access to the sea, as well as a crater.[verification needed]

In 2006, a geologist reported that the islets formed 4.5 million years ago and are (in a geological sense) quickly eroding.[8]

Tourism

Restricted public access to the rocks for a variety of purposes is provided by ferry from Ulleng Island.[9] In 2022, 280,312 tourists visited the islands, averaging 500 visitors per day.[1]

Distances

The Liancourt Rocks are located at about 37°14′N 131°52′E / 37.233°N 131.867°E.[10] The western islet is located at 37°14′31″N 131°51′55″E / 37.24194°N 131.86528°E and the Eastern Islet is located at 37°14′27″N 131°52′10″E / 37.24083°N 131.86944°E.

The Liancourt Rocks are situated at a distance of 211 kilometres (114 nmi) from the main island of Japan (Honshu) and 216.8 kilometres (117.1 nmi) from mainland South Korea. The nearest Japanese island, Oki Islands, is at a distance of 157 kilometres (85 nmi),[11] and the nearest Korean island, Ulleungdo, is 87.4 kilometres (47.2 nmi).[12][11]

Climate

Owing to their location and small size, the Liancourt Rocks can have harsh weather. If the swell is greater than 3 to 5 metres, then landing is not possible, so on average ferries can only dock about once in forty days.[13] Overall, the climate is warm and humid, and heavily influenced by warm sea currents. Precipitation is high throughout the year (annual average—1,383.4 millimetres or 54.46 inches), with occasional snowfall.[14] Fog is common. In summer, southerly winds dominate. The water around the islets is about 10 °C (50 °F) in early spring, when the water is coldest, warming to about 24 °C (75 °F) in late summer.

Ecology

The islets are volcanic rocks, with only a thin layer of soil and moss.[15] About 49 plant species, 107 bird species, and 93 insect species have been found to inhabit the islets, in addition to local marine life with 160 algal and 368 invertebrate species identified.[16] Although between 1,100 and 1,200 litres of fresh water flow daily, desalinization plants have been installed on the islets for human consumption because existing spring water suffers from guano contamination.[citation needed] Since the early 1970s trees and some types of flowers were planted.[citation needed] According to historical records, there used to be trees indigenous to Liancourt Rocks, which have supposedly been wiped out by overharvesting and fires caused by bombing drills over the islets.[d] A recent investigation, however, identified ten spindle trees aged 100–120 years.[17][18] Cetaceans such as Minke whales, orcas, and dolphins are known to migrate through these areas.[19][20][21]

Pollution and environmental destruction

Records of the human impact on the Liancourt Rocks before the late 20th century are scarce, although both Japanese and Koreans claim to have felled trees and killed Japanese sea lions there for many decades.[22][23]

There are serious pollution concerns in the seas surrounding the Liancourt Rocks. In 2004, a malfunction in the sewage water treatment system established on the islets caused sewage produced by inhabitants of the Liancourt Rocks, such as South Korean Coast Guards and lighthouse staff, to be dumped directly into the ocean. Significant water pollution was observed; sea water turned milky white, sea vegetation died, and coral reefs were calcified. The pollution also caused loss of biodiversity in the surrounding seas. In November 2004, eight tons of malodorous sludge was being dumped into the ocean every day.[24] Efforts have since been made by both public[25] and private[26] organizations to reduce the level of pollution surrounding the Rocks.

Construction

South Korea has carried out construction work on the Liancourt Rocks; by 2009, the islands had a lighthouse, helicopter pad,[27] and a police barracks.[28] In 2007, two desalination plants were built capable of producing 28 tons of clean water every day.[29] Both of the major South Korean telecommunications companies have installed cellular telephone towers on the islets.[30]

History

Whaling

U.S. and French whaleships cruised for right whales off the rocks between 1849 and 1892.[31]

Demographics and economy

In February 2017, there were two civilian residents, two government officials, six lighthouse managers, and 40 members of the coast guard living on the islets.[1] Since the South Korean coast guard was sent to the islets, civilian travel has been subject to South Korean government approval; they have stated that the reason for this is that the islet group is designated as a nature reserve.[32]

In March 1965, Choi Jong-duk moved from the nearby Ulleungdo to the islets to make a living from octopus fishing. He also helped install facilities from May 1968. In 1981, Choi Jong-duk changed his administrative address to the Liancourt Rocks, making himself the first person to officially live there. He died there in September 1987. His son-in-law, Cho Jun-ki, and his wife also resided there from 1985 until they moved out in 1992. Meanwhile, in 1991, Kim Sung-do and Kim Shin-yeol transferred to the islets as permanent residents, still continuing to live there. In October 2018, Kim Sung-do died, thus Kim Shin-yeol is the last civilian resident still living on the islands.[33][34][35][36]

The South Korean government gave its approval to allow 1,597 visitors to visit the islets in 2004. Since March 2005, more tourists have received approval to visit. The South Korean government lets up to 70 tourists land at any given time; one ferry provides rides to the islets every day.[37] Tour companies charge around 350,000 Korean won per person (about US$310 as of 2019[update]).[38]

Sovereignty dispute

Sovereignty over the islands has been an ongoing point of contention in Japan–South Korea relations. There are conflicting interpretations about the historical state of sovereignty over the islets.

South Korean claims are partly based on references to an island called Usando (우산도; 于山島; 亐山島) in various medieval historical records, maps, and encyclopedia such as Samguk Sagi, Annals of Joseon Dynasty, Dongguk Yeoji Seungnam, and Dongguk munhon bigo. According to the South Korean view, these refer to today's Liancourt Rocks.[citation needed] Japanese researchers of these documents have claimed the various references to Usan-do refer at different times to Jukdo, its neighboring island Ulleungdo, or a non-existent island between Ulleungdo and Korea.[e] The first printed usage of the name Dokdo was in a Japanese log book in 1904.[39]

North Korea also regards the islands as Korean, and as it claims the entirety of Korea, North Korea claims the islands as its own and contests Japan's claim to the islands alongside South Korea.[40]

-

South Korean stamps depicting the Liancourt Rocks from 1954

-

A South Korean police boat approaches the dock on the Liancourt Rocks' East Islet.

Natural Monument of South Korea

The Liancourt Rocks were designated as a breeding ground for band-rumped storm petrels, streaked shearwaters, and black-tailed gulls as Natural Monument #336 of South Korea on November 29, 1982.[41]

See also

Notes

- ^ Korean: 독도; Hanja: 獨島; IPA: [tok̚t͈o]; lit. 'solitary island[s]' or 'lonely island[s]'.

- ^ Japanese: 竹島; IPA: [takeɕima]; lit. 'bamboo island[s]'.[3]

- ^ Pronounced [lə ljɑ̃kuʁ]; named in honor of François Alexandre Frédéric, Duke of La Rochefoucauld and Liancourt.

- ^ "There are records attesting to the existence of trees [on Liancourt Rocks] in the past" (BAEK In-ki, SHIM Mun-bo & Korea Maritime Institute 2006, p. 48)

- ^ "Such description ... rather reminds us of Utsuryo Island" (para. 2); "A study ... criticizes ... that Usan Island and Utsuryo Island are two names for one island." (para. 3); and "that island does not exist at all in reality" (para. 4 – "10 Issues of Takeshima, MOFA (Article 2)" (PDF). Ministry of Foreign Affairs (Japan). February 2008. p. 4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2008.

Inline citations

- ^ a b c "Dokdo Residents". Gyeongsangbuk-do Province. Retrieved 17 February 2021.

- ^ Fern 2005, p. 78: "Since the end of World War II, Japan and Korea have contested ownership of these islets, given the name Liancourt Rocks by French whalers in the mid-1800s and called that by neutral observers to this day".

- ^ BBC staff 2006.

- ^ a b c d e Gyeongsangbuk-do Province 2017b.

- ^ BBC staff 2008.

- ^ Kirk 2008.

- ^ 울릉군리의명칭과구역에관한조례 [개정 2000. 4. 7 조례 제1395호] [Act 1395 amending Chapter 14-2, Ri-Administration under Ulleung County, Local Autonomy Law, Ulleung County] (in Korean). "2000년 4월 7일 울릉군조례 제1395호로 독도리가 신설됨에 따라 독도의 행정구역이 종전의 경상북도 울릉군 울릉읍 도동리 산42~76번지에서 경상북도 울릉군 울릉읍 독도리 산1~37번지로 변경 됨."

Translation: "Pursuant to Act 1395 amending Chapter 14-2, Ri-Administration under Ulleung County, Local Autonomy Law, Ulleung County, passed March 20, 2000, enacted April 7, 2000, the administrative designation of Dokdo addresses as 42 to 76, Dodong-ri, Ulleung-eup, Ulleung County, North Gyungsang Province, is changed to address 1 to 37, Dokdo-ri, Ulleung-eup, Ulleung County, North Gyungsang Province." 조회 (in Korean). Archived from the original on 1 March 2009. Retrieved 12 September 2008. - ^ "독도ㆍ울릉도 `침몰하고 있다'"<손영관교수>. Yonhap News Agency (in Korean). 1 December 2006. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016. Retrieved 1 January 2015.

- ^ "독도 : 독도입도안내 페이지 입니다.아름다운 신비의 섬 - 울릉군". www.ulleung.go.kr. Archived from the original on 13 October 2022. Retrieved 13 October 2022.

- ^ Gyeongsangbuk-do Province 2017c.

- ^ a b "The Issue of Takeshima". Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan. Retrieved 26 October 2012.

- ^ BAEK In-ki, SHIM Mun-bo & Korea Maritime Institute 2006, pp. 20–22.

- ^ Gyeo ngbuk Province 2001b.

- ^ Gyeongsangbuk-do Province 2017a.

- ^ Gyeo ngbuk Province 2001a.

- ^ 독도 자연생태계 정밀조사결과(요약) [A comprehensive survey of the natural ecosystems of Liancourt Rocks (synopsys)] (in Korean). Archived from the original on 22 July 2011.

- ^ 독도 자생 사철나무 군락 첫 발견 [Indigenous Spindle Tree Colony Found on Liancourt Rocks] (in Korean). [dead link]

- ^ 독도 자생 사철나무 100년 이상 된 자생식물 [Liancourt Rock Spindle Trees Over 100 Years Old] (in Korean).

- ^ 독도수비 해경, 그물걸린 범고래 구조 - 멸종위기 해양생물 보호 적극적인 조치 기대. K07011002K (in Korean): ENVIROASIA. 2007. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ 独島警備の海洋警察、網にかかったシャチ救出. K07011002J (in Japanese). Translated by Koike T.: ENVIROASIA 2007. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 10 June 2014.

- ^ "동해 고래, 한미관계 뿐 아니라 독도 역사와도 연결". 2017. Retrieved 21 August 2017.

- ^ 국민일보 (Gookmin Daily). "독도‘실효적 지배’새 근거 (New Evidence of effective control), 1890년 이전부터 독도서 강치잡이 (Sea lion hunting before 1890) [26 July 2006"]

- ^ Japan: Outline of Takeshima Issue

- ^ 독도 오수정화시설이 동해바다 오염 주범?. Imaeil (in Korean). 28 September 2007. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 15 April 2009.

- ^ 독도 바다쓰레기 청소 6월2일부터 석달간 [Three-Month Cleanup for Dokdo's Marine Garbage Starts from June 2] (in Korean).

- ^ 나무 심고 오물 줍고…아름다운 ‘독도 사랑’ (in Korean). 5 July 2010. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- ^ Vladivostok News report Archived 23 August 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Choe 2008.

- ^ KOIS staff 2007a.

- ^ KOIS staff 2007.

- ^ Cambria, of New Bedford, Apr. 29, 1849, Nicholson Whaling Collection; Cape Horn Pigeon, of New Bedford, Apr. 19, 1892, Kendall Whaling Museum.

- ^ On 13 December 1997 the "Special Act on the Preservation of Ecosystem in Island Areas Including Dokdo Island" was enacted by the South Korean parliament. The title of the Natural Monument No. 336, the Dokdo Seaweed Habitat, was changed to the Dokdo National Nature Reserve in December 1999. "Dokdo in History: Chronology". The National Assembly of the Republic of Korea.

- ^ Hong, Euny (2014). The birth of Korean cool: how one nation is conquering the world through pop culture (1st ed.). New York: Picador. ISBN 978-1-250-04511-9.

- ^ Lee Tae-hee (13 February 2019). "Widow to remain sole Dokdo resident, authorities confirm". The Korea Herald.

- ^ McKirdy, Euan; Jeong, Sophie (15 February 2019). "Widow, 81, sole resident of remote island disputed by South Korea and Japan". CNN.

- ^ 竹島人口は7万人 4年で倍増 日本人17人も住民登録している!?. KoreaWorldTimes (in Japanese). 16 August 2021. Retrieved 6 October 2021.

- ^ Ha 2008.

- ^ "Life in Dokdo". Cyber Dokdo of Korea. Archived from the original on 11 January 2013.

- ^ ""Logbooks of the Japanese Warship Niitaka September 25th 1904"". Dokdo Takeshima The Historical Facts of the Dispute. 1 September 2008.

- ^ Agency, United States Central Intelligence; Office, Government Publications (2016). The World Factbook 2016-17. Government Printing Office. p. 406. ISBN 9780160933271.

- ^ "문화재(천연기념물)보호구역지정". 2 December 1982.

References

- BAEK In-ki; SHIM Mun-bo; Korea Maritime Institute (December 2006), A study of Distance between Ulleungdo and Dokdo and Ocean Currents (울릉도와 독도의 거리와 해류에 관한 연구), pp. 20–22, ISBN 978-89-7998-340-1, archived from the original on 12 January 2013

- BBC staff (20 April 2006), Seoul and Tokyo hold island talks, BBC

- BBC staff (27 July 2008), "Island row hits Japanese condoms", BBC News

- Fern, Sean (Winter 2005), "Tokdo or Takeshima? The International Law of Territorial Acquisition in the Japan-Korea Island Dispute", Stanford Journal of East Asian Affairs, 5 (1)

- Gyeongsangbuk-do Province (28 September 2017a), "Climate", Dokdo, Beautiful island of Korea, Korean Government

- Gyeongsangbuk-do Province (28 September 2017b), "Composition", Dokdo, Beautiful island of Korea, Korean Government

- Gyeongsangbuk-do Province (28 September 2017c), "Location", Dokdo, Beautiful island of Korea, Korean Government

- Gyeo ngbuk Province (2001a), "Natural Environment", Cyber Dokdo, Korean Government, archived from the original on 29 July 2014

- Gyeo ngbuk Province (2001b), "Visit Dokdo", Cyber Dokdo, Korean Government, archived from the original on 29 July 2014

- Ha, Michael (26 August 2008), "A Unique Trip to Dokdo—Islets in the News", The Korea Times, archived from the original on 4 March 2016

- Kirk, Donald (26 July 2008), "Seoul has desert island dreams", Asia Times Online, archived from the original on 1 March 2009

- KOIS staff (12 January 2007), Cell phones give Korean ring to Dokdo, Korea.net, archived from the original on 2 March 2009

- KOIS staff (12 June 2007a), Doosan pours big drink for Dokdo residents, Korea.net, archived from the original on 2 March 2009

- Choe, Sang-Hun (28 August 2008), "A fierce Korean pride in a lonely group of islets", International Herald Tribune, archived from the original on 28 August 2008

- Yonhap staff (20 July 2011), N. Korea denounces Japan's vow to visit island near Dokdo, Yonhap News Agency

External links

South Korea

- Dokdo Official Website

- Dokdo Research Institute (Korea)

- The Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Korea

- 대한민국외교부 (22 April 2014). "Dokdo, Beautiful Island of Korea". YouTube. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021.

Japan

- "Takeshima Archives Potal" (Cabinet Secretariat, Japan)

- "Commissioned Research Report on Archives of Takeshima" Cabinet Secretariat, Japan

- "Takeshima" (Shimane prefectural office, Japan)

- Japanese Territory / "Takeshima" (MOFA, Japan)

- "10 Issues of Takeshima" Northeast Asia Division, Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau, MOFA, Japan (February 2008)

- "TAKESHIMA: 10 points to understand the Takeshima Dispute" Northeast Asia Division, Asian and Oceanian Affairs Bureau, MOFA, Japan (March 2014)

- MOFA, Japan (31 October 2013). "Takeshima - Seeking a Solution based on Law and Dialogue". YouTube. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021.