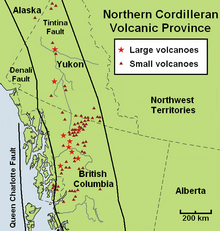

The geography of northwestern British Columbia and Yukon, Canada is dominated by volcanoes of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province formed due to continental rifting of the North American Plate. It is the most active volcanic region in Canada.[1] Some of the volcanoes are notable for their eruptions, for instance, Tseax Cone for its catastrophic eruption estimated to have occurred in the 18th century which was responsible for the death of at least 2,000 Nisga'a people from poisonous volcanic gases,[2] the Mount Edziza volcanic complex for at least 20 eruptions throughout the past 10,000 years, and The Volcano (also known as Lava Fork volcano) for the most recent eruption in Canada during 1904.[3] The majority of volcanoes in the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province lie in Canada while a very small portion of the volcanic province lies in the U.S. state of Alaska.

Volcanoes of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province are a part of the Pacific Ring of Fire. The largest and most persistent volcanoes are the Mount Edziza volcanic complex and Level Mountain in northwestern British Columbia which have had volcanic activity for millions of years. In the past 7.5 million years, the Mount Edziza volcanic complex has had five phases of volcanic activity while Level Mountain north of Edziza has had three phases of volcanic activity in the past 14.9 million years.[4] The 1,000 km2 (390 sq mi) Mount Edziza volcanic complex has been made into a provincial park since 1972 to protect its volcanic landscape. The 102 Northern Cordilleran volcanoes in the list below are grouped into their political regions in north–south order.

Scope

editThere is no single standard definition for a volcano. It can be defined from individual vents, volcanic edifices or volcanic fields. Interior of ancient volcanoes may have been eroded, creating a new subsurface magma chamber as a separate volcano. Many contemporary volcanoes rise as young parasitic cones from flank vents or at a central crater. Some volcanoes are grouped into one volcano name, for instance, the Mount Edziza volcanic complex, although individual vents are named by local people. The status of a volcano, either active, dormant or extinct, cannot be defined precisely. An indication of a volcano is determined by either its historical records, potassium-argon dating, radiocarbon dating, or geothermal activities.

The primary source of the list below is taken from the Geological Survey of Canada website, compiled by the Earth Sciences Sector of Natural Resources Canada, in which Northern Cordilleran volcanoes in the past 66.4 million years are listed.[5] The Geological Survey of Canada use a catalogue of volcanoes grouped by volcano fields, lava fields and mountain ranges.[5] The Geological Survey of Canada list is the most complete list of volcanoes in the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province, but work of understanding the frequency and eruption characteristics at volcanoes in Canada is a slow process.[6] This is because most of Canada's dormant and potentially active volcanoes are located in isolated jagged regions, very few scientists study Canadian volcanoes and the provision of money in the Canadian government is limited.[6] Because of these issues, scientists that study Canada's volcanoes have a basic understanding of Canada's volcanic heritage and how it might impact people in the future.[6] Therefore, instead of using the dates of recorded eruptions, the Geological Survey of Canada mostly uses geological epochs for estimating when a volcano last erupted. Geological epoches include the Cenozoic (66.4 million years ago to present)[7] and its subdivisions Miocene (23.7 to 5.3 million years ago),[8] Pliocene (5.3 to 1.6 million years ago),[9] Quaternary (1.6 million years ago to present),[10] Pleistocene (1.6 to 0.01 million years ago)[11] and Holocene (0.01 million years ago to present).[12]

Political groups

editAlaska

editThe northernmost portion of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province extends just across the Alaska-Yukon border into the Southeast Fairbanks Census Area of eastcentral Alaska. Here, a single cinder cone, dated at 177,000 years old occurs within the metamorphic and granitic composed upland of the Yukon–Tanana Terrane.[4][13] Prindle Volcano is approximately 31 km (19 mi) west of the Alaska-Yukon border.[4]

| Volcanoes | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Name | Type | Last eruption | Location |

| Prindle Volcano | Cinder cone | Pleistocene | 63°43′N 141°37′W / 63.72°N 141.62°W |

Yukon

editThe central portion of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province extends through Yukon where very few Northern Cordilleran volcanoes exist. Near the junction of the Yukon and Pelly rivers in central Yukon lies the Fort Selkirk Volcanic Field.[14] It is the northernmost Holocene age volcanic field in Canada, consisting of a sequence of valley-filling basalt and basanite lava flows.[14] Further south near the capital city of Whitehorse, a group of volcanoes and lava flows were constructed near Alligator Lake possibly in the past 10,000 years.[15]

British Columbia

editOver half of the Northern Cordilleran volcanoes are located in northwestern British Columbia. This portion is where the most recent eruptions in Canada and of the Northern Cordilleran Volcanic Province have occurred, including the catastrophic 18th century eruption of Tseax Cone and the 1904 eruption of The Volcano.[3][16]

The Northern Cordilleran volcanoes of British Columbia comprises shield volcanoes, stratovolcanoes, subglacial volcanoes, lava domes and a large number of small cinder cones and associated lava plains.[4] The Northern Cordilleran volcanoes of northwestern British Columbia are disposed along short, northerly trending segments which are unmistakably involved with north-trending rift structures including synvolcanic grabens and grabens with one major fault line along only one of the boundaries (half-grabens) similar to those associated with the East African Rift, which extends from the Afar Triple Junction southward across eastern Africa.[4]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Stikine volcanic belt". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Geological Survey of Canada. 2008-02-13. Archived from the original on 2009-06-08. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Tseax Cone". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Geological Survey of Canada. 2009-03-10. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ a b "Lava Forks Provincial Park". BC Parks. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ a b c d e Wood, Charles A.; Kienle, Jürgen (1990). Volcanoes of North America: United States and Canada. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 109, 114, 121, 122, 123, 124, 125. ISBN 0-521-43811-X.

- ^ a b "Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes". Geological Survey of Canada. 2008-02-13. Archived from the original on 2009-06-08. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ a b c "Volcanoes". Natural Resources Canada. 2007-09-05. Archived from the original on 2009-02-17. Retrieved 2009-06-21.

- ^ "Chikoida Mountain". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Geological Survey of Canada. 2009-03-10. Archived from the original on 2011-06-04. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Armadillo Peak". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Geological Survey of Canada. 2009-03-10. Archived from the original on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Maitland Volcano". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Geological Survey of Canada. 2009-03-10. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Cracker Creek cone". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Geological Survey of Canada. 2009-03-10. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Kawdy Mountain". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Geological Survey of Canada. 2009-03-10. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Hoodoo Mountain". Catalogue of Canadian volcanoes. Geological Survey of Canada. 2009-03-10. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ "Map of Canadian volcanoes". Volcanoes of Canada. Geological Survey of Canada. 2008-02-13. Archived from the original on 2006-07-14. Retrieved 2009-06-22.

- ^ a b "Fort Selkirk". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ "Alligator Lake". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2009-06-24.

- ^ "Tseax River Cone". Global Volcanism Program. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2009-06-24.