There have been a variety of ethnic groups in Baltimore, Maryland and its surrounding area for 12,000 years. Prior to European colonization, various Native American nations have lived in the Baltimore area for nearly 3 millennia, with the earliest known Native inhabitants dating to the 10th millennium BCE. Following Baltimore's foundation as a subdivision of the Province of Maryland by British colonial authorities in 1661, the city became home to numerous European settlers and immigrants and their African slaves. Since the first English settlers arrived, substantial immigration from all over Europe, the presence of a deeply rooted community of free black people that was the largest in the pre-Civil War United States, out-migration of African-Americans from the Deep South, out-migration of White Southerners from Appalachia, out-migration of Native Americans from the Southeast such as the Lumbee and the Cherokee, and new waves of more recent immigrants from Latin America, the Caribbean, Asia and Africa have added layers of complexity to the workforce and culture of Baltimore, as well as the religious and ethnic fabric of the city. Baltimore's culture has been described as "the blending of Southern culture and [African-American] migration, Northern industry, and the influx of European immigrants—first mixing at the port and its neighborhoods...Baltimore’s character, it’s uniqueness, the dialect, all of it, is a kind of amalgamation of these very different things coming together—with a little Appalachia thrown in...It’s all threaded through these neighborhoods", according to the American studies academic Mary Rizzo.[1]

Early history

editThe Baltimore area has been inhabited by Native Americans since at least the 10th millennium BC, when Paleo-Indians first settled in the region. One Paleo-Indian site and several Archaic period and Woodland period archaeological sites have been identified in Baltimore, including four from the Late Woodland period.[2] During the Late Woodland period, the archaeological culture that is called the "Potomac Creek complex" resided in the area from Baltimore to the Rappahannock River in Virginia.[3]

Prior to the establishment of Baltimore as a city, the Piscataway tribe of Algonquians inhabited the Baltimore area. In 1608, Captain John Smith traveled 170 miles from Jamestown to the upper Chesapeake Bay, leading the first European expedition to the Patapsco River, named after the native Algonquians who fished shellfish and hunted.[4] The name "Patapsco" is derived from pota-psk-ut, which translates to "backwater" or "tide covered with froth" in Algonquian dialect.[5] The Chesapeake Bay was named after the Chesapeake tribe of Virginia. "Chesapeake" is derived from the Algonquian word Chesepiooc referring to a village "at a big river." It is the seventh oldest surviving English place-name in the U.S., first applied as "Chesepiook" by explorers heading north from the Roanoke Colony into a Chesapeake tributary in 1585 or 1586.[6]

In 2005, Algonquian linguist Blair Rudes "helped to dispel one of the area's most widely held beliefs: that 'Chesapeake' means something like 'Great Shellfish Bay.' It does not, Rudes said. The name might actually mean something like 'Great Water,' or it might have been just a village at the bay's mouth."[7] Soon after John Smith's voyage, English colonists began to settle in Maryland. The English were initially frightened by the Piscataway because of their body paint and war regalia, even though they were a peaceful tribe. The chief of the Piscataway was quick to grant the English permission to settle within Piscataway territory and cordial relations were thereafter established between the English and the Piscataway.[8]

Beginning in the 1620s, English settlers from the Colony of Virginia began to trade with the Algonquians, in particular the Piscataway tribe. Since the northern part of the Chesapeake Bay area had more trees, there were also more beavers. The colonists from Virginia traded English cloth and metal tools in exchange for beaver pelts. This trade was supported by Lord Baltimore, who felt that more revenue could be gained from taxation of the fur trade than from tobacco farming. Lord Baltimore also wanted to maintain friendly relations with the native Algonquians in order to create a buffer from the Susquehannock, an Iroquoian-speaking tribe to the north that was hostile to the English presence. In exchange for cooperation with the English colonists, tribes on the Eastern Shore of the United States were given grants from English proprietors that protected their lands. The tribes paid for the grants by exchanging beaver belts.

A number of English fur traders helped pay the rents for Native Americans in order to prevent tobacco farmers from driving the Native Americans off of their lands. Nonetheless, English tobacco farmers gradually acquired more and more land from Native Americans, which hindered Native Americans from moving around freely in search of food. While the English had established treaties with the Native Americans that protected their rights to "hunting, fowling, crabbing, and fishing", in practice the English did not respect the treaties and the Native Americans were eventually moved to reservations.

In 1642, the Province of Maryland declared war on several Native American groups, including the Susquehannocks. The Susquehannocks were armed with guns they had received from Swedish colonists in the settlement of New Sweden. The Swedes were friendly with the Susquehannock and wanted to maintain a trading relationship, in addition to wanting to prevent the English from expanding their presence further into Delaware. With the assistance of the Swedes, the Susquehannock defeated the English in 1644. In 1652, the Susquehannock made peace with Maryland and ceded large tracts of land to colony. The tribe had incurred a loss in a war with the Iroquois, and could not maintain two wars at once. Because both the Susquehannock and the English considered the Iroquois to be their enemy, they decided to cooperate to prevent Iroquois expansion into their territories. This alliance between the Susquehannock and the English lasted for 20 years. However, the English badly treated their Susquehannock allies. In 1674, the English forced the Susquehannock to relocate to the shores of the Potomac River.[9]

Ethnic groups

editAfrican Americans

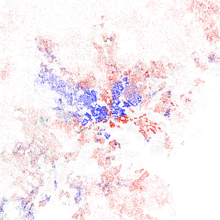

editAfrican Americans are the majority racial and cultural group in Baltimore. The history of the African Americans in Baltimore dates back to the 17th century when the first African slaves were being brought to the Province of Maryland. Majority white for most of its history, Baltimore transitioned to having a black majority in the 1970s.[10] As of the 2010 Census, African Americans are the majority population of Baltimore at 63% of the population, with a total population of 417,009 people.[11] As a majority black city for the last several decades with the 5th largest population of African Americans of any city in the United States, African Americans have had an enormous impact on the culture, dialect, history, politics, and music of the city. Unlike many other Northern cities whose African-American populations first became well-established during the Great Migration, Baltimore has a deeply rooted African-American heritage, being home to the largest population of free black people half a century before the Emancipation Proclamation. The migrations of Southern and Appalachian African-Americans between 1910 and 1970 brought thousands of African-Americans to Baltimore, transforming the city into the second northernmost majority-black city in the United States after Detroit. The city's African-American community is centered in West Baltimore and East Baltimore. The distribution of African Americans on both the West and the East sides of Baltimore is sometimes called "The Black Butterfly", while the distribution of white Americans in Central and Southeast Baltimore is called "The White L."[12]

African immigrants

editAs of 2010, there were 28,834 immigrants from Sub-Saharan Africa in Baltimore.[13]

An annual festival called FestAfrica is held in Patterson Park in order to teach non-Africans about various African cultures and histories. The event is typically attended by 4,000 people and features a picnic, food vendors, and entertainment.[14]

In 2011, speakers of various languages of Africa were the third largest group of language speakers in Baltimore among those who spoke English "less than very well", after speakers of Spanish or Spanish Creole and speakers of Chinese. Additionally, 6,862 African immigrants lived in Baltimore, making Africa the third largest region of origin for immigrants after Latin America and Asia.[15]

Cape Verdeans

editIn 2011, immigrants from Cape Verde were the one-hundredth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Cameroonians

editIn 2011, immigrants from Cameroon were the forty-fourth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Eritreans

editThere is a small Eritrean immigrant community in Baltimore. Most are refugees and have settled in the northeastern part of the city.[16]

In 2011, immigrants from Eritrea were the fiftieth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Ethiopians

editAround 75,000 Ethiopian Americans reside in Maryland. Of those, between 30,000 and 50,000 live in Greater Baltimore. The population generally works as small business owners, cab drivers, beauticians and medical technicians.[17] It is represented by the Ethiopian Community Center in Baltimore Inc. (ECCB), which provides educational and support services to the city's Ethiopian residents.[18]

In the area where Baltimore's historic Chinatown is located, there is an increasing Ethiopian population. There are multiple Ethiopian businesses, including restaurants, a café, and a market. This enclave, located on the 300 block of Park Avenue, is sometimes referred to as Little Ethiopia.[19]

In 2011, immigrants from Ethiopia were the twenty-third largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Ghanaians

editIn 2011, immigrants from Ghana were the twenty-second largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Kenyans

editThere is a Kenyan American population living in Baltimore, many of whom have relatives living in Kenya.[20]

In 2011, immigrants from Kenya were the thirty-third largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Liberians

editThere were over 2,500 Liberian Americans living in Baltimore as of 2014.[21]

In 2011, immigrants from Liberia were the thirty-second largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Nigerians

editAn annual Nigerian festival is held in Baltimore called the Naija Fest. It is sponsored by the Nigerian Youth Association of Maryland and features art, dance, music, and a feast.[22]

In 2011, immigrants from Nigeria were the sixth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore, making Nigerians the largest foreign-born African population in the city.[15]

The third most spoken language in Baltimore after English and Spanish is Yoruba, a language spoken in Nigeria, and 1.72 percent of Baltimore County residents speak Yoruba.[23] Yoruba is also the second most spoken foreign language in Baltimore schools.[24][25]

Sierra Leoneans

editIn 2011, immigrants from Sierra Leone were the forty-sixth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Sudanese

editIn February 2011, the Sudanese community of Baltimore numbered only 185 people. Due to South Sudan's independence from Sudan, many South Sudanese have returned to their homeland. Prior to independence, Baltimore's Sudanese community numbered 300 people.[26]

In 2011, immigrants from Sudan were the twenty-ninth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Asian Americans

editThe largest Asian ethnic groups are Koreans and Indians. Smaller numbers of Filipinos, Chinese, Japanese, and Vietnamese also exist. The Asian population is concentrated near Johns Hopkins' Homewood Campus of Johns Hopkins University, as well as in Downtown and Midtown Baltimore.[15]

There were 9,824 Asian Americans living in Baltimore city in 2000. This is 1.51% of the population.[11] In the same year, 7,879 Asian-born immigrants lived in Baltimore, comprising 26.6% of all foreign-born residents of the city. This made Asia the second largest region of origin for immigrants after Latin America.[27]

Per data published in September 2014, 10,678 Asian immigrants lived in Baltimore, making Asia the second largest region of origin for immigrants after Latin America. In 2011, Asian languages spoken among those who spoke English "less than very well" included Chinese, Korean, Tagalog, Vietnamese, Urdu, Japanese, Laotian, Hindi, and Thai.[15]

Bhutanese

editThere is a community of Bhutanese refugees in Baltimore.[28]

Burmese

editThere is a community of Burmese refugees in Baltimore.[28] Other Burmese refugees have settled in nearby Howard County.[29]

In 2011, immigrants from Burma were the twenty-fifth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Chinese

editChinese Americans number 13,877 people, 0.5% of Baltimore.[13] In 2000, the Chinese language was spoken at home by 4,110 people in Baltimore.[30] During the 1990s the Chinese were the second-largest Asian group in the city, after Koreans.[31]

There existed two Chinatowns in Baltimore; the first one existed on the 200 block of Marion Street during the 1880s. A second location was on Park Avenue, which was dominated by laundries and restaurants. The Chinese population initially came because of the transcontinental railroad, however, the Chinese population never exceeded 400 as of 1941 and there were even fewer in the 1930 census.[32] During segregation, Chinese children were classified as "White" and went to the White schools. The Chinatown was largely gone by the First World War due to urban renewal.[33] By the 1970s, hardly any Chinese people lived in the city.[34] There are now debates about whether Baltimore should revitalize the old Chinatown in the location of Park Avenue or build a new one about a mile north at Charles Street and North Avenue.[35]

In 2011, immigrants from China (excluding Hong Kong and Taiwan) were the fifth-largest foreign-born population in Baltimore, making mainland Chinese immigrants the largest foreign-born Asian population in the city. Immigrants from Taiwan were the sixteenth-largest foreign-born population and immigrants from Hong Kong were sixty-fifth. The Chinese language was the second most commonly spoken language, after Spanish, among people who spoke English "less than very well".[15]

During the 2015 Baltimore protests, the Bloods gang allegedly protected Black-owned stores by directing rioters to loot and vandalize Chinese-owned stores instead.[36]

Filipinos

editFilipino Americans numbered 8,509 people in 2000, 0.3% of the Baltimore metropolitan area.[13]

In 2000, the Tagalog language is spoken at home by 2,180 people in Baltimore.[30]

An annual Philippine-American Festival is held in Towson, a suburb of Baltimore. The festival includes Filipino cuisine, dances, and a parade.[37]

In 2011, immigrants from the Philippines were the eighth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore and the Tagalog language was the tenth most commonly spoken language among those who spoke English "less than very well".[15]

Indians

editIndian Americans numbered 15,908 people in 2000, 0.6% of the Baltimore metropolitan area.[13]

Indian-Americans in the Baltimore area number roughly 39,000, making up the largest Asian group in Metro Baltimore at 1.4 percent of the population.[38]

The Rathayatra Parade, India's ancient Festival of Chariots, is held once a year in Baltimore. The parade begins outside Oriole Park at Camden Yards and ends at the Inner Harbor, where the Festival of India is held. The festival is sponsored by the Hare Krishna Temple of Catonsville and features live classical Indian music and dancing, arts and theater, literature, and a vegetarian feast.[39]

In 2011, immigrants from India were the tenth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore. In the same year, among immigrants who spoke English "less than very well", Urdu and Hindi were the thirteenth and twenty-fourth most commonly spoken languages in the city respectively; speakers of other Indic languages were the eighth largest group.[15] Telugu, a language native to Southern India, is the second most spoken South Asian language in the Baltimore metro area, with roughly 6,000 speakers of Telugu.[citation needed]

Indonesians

editIn 2011, immigrants from Indonesia were the seventy-second largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Japanese

editJapanese Americans are a small community in Baltimore. They numbered 2,185 people in 2000, 0.1% of the Baltimore metropolitan area.[13] During the 1990s, the Japanese were the third largest Asian group in the city after Koreans and the Chinese.[31]

In the 1930 United States Census, there were fewer than 1,000 Japanese-born people in Baltimore.[32]

There is a Japanese-American Fellowship Society, founded during the 1970s, which is meant to bring the Japanese culture to the people of Baltimore.[31] There were hardly any Japanese people living in the city at the time the society was formed.[34]

In 2011, immigrants from Japan were the thirtieth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore and the Japanese language was the fifteenth most commonly spoken language among those who spoke English "less than very well".[15]

Koreans

editThe Korean population in Baltimore dates back to the mid-20th century. The Korean American community in numbered 1,990 in 2010, making up 0.3% of the city's population.[13] At 93,000 people, the Baltimore–Washington metropolitan area has the third largest Korean American population in the United States.[40] The Baltimore metropolitan area is home to 35,000 Koreans making up roughly 1.2 percent of the population, many of whom live in suburban Howard County. In 2000, the Korean language is spoken at home by 3,970 people in Baltimore.[30]

In 2011, immigrants from Korea were the seventh largest foreign-born population in Baltimore, making Koreans the second largest foreign-born Asian population after mainland Chinese.[15]

Laotians

editIn 2011, immigrants from Laos were the sixty-second largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Nepali

editIn 2011, immigrants from Nepal were the forty-third largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15] Nepalis are the fifth largest Asian ethnic group in Baltimore,[41] numbering roughly 0.2 percent of the population.

Pakistanis

editIn 2011, immigrants from Pakistan were the thirty-fifth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15] Urdu is the most spoken South Asian language in the Baltimore metro area, with over 9,000 speakers.[citation needed]

Thais

editIn 2011, immigrants from Thailand were the fifty-fourth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Vietnamese

editVietnamese Americans numbered 3,616 people in 2000, 0.1% of the Baltimore metropolitan area.[13]

A Vietnamese pho restaurant exists in Hollins Market.[42]

In 2011, immigrants from Vietnam were the twenty-eighth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore and the Vietnamese language was the twelfth most commonly spoken language among those who spoke English "less than very well".[15]

Hispanics and Latinos

editBaltimore's Hispanic population is relatively new. Hispanics made up about 4.2% of Baltimore's population in 2010, which is lower than many other cities of similar sizes in the Mid-Atlantic region. Unlike Philadelphia, where Puerto Ricans make up the majority of Hispanics, or Washington, DC, where Salvadorans form a slight plurality over other Hispanic groups, in Baltimore, the Hispanic population is fairly diverse for its size. The city has near equal populations of Mexicans, Puerto Ricans, and Salvadorans, with a smaller number of Hispanics coming from countries like the Dominican Republic, Honduras, Guatemala, Cuba, and Colombia. However, Hispanic populations originating from Mexico and Central America have been growing at a faster rate. Most of Baltimore's Hispanic population is in the Southeast section of the city, in areas around Patterson Park and north of Eastern Avenue, especially Highlandtown. Significant Hispanic presence can be seen going in a southeast-ward direction towards Dundalk. Hispanics are starting to act as a medium creating a diverse community wedged between the predominantly Black community north of Orleans Street and the predominantly White community south of Eastern Avenue. Another noticeable pattern is that neighborhoods west of Linwood Avenue such as Upper Fell's Point and Butchers Hill, Hispanics are mostly made up of first and second generation immigrants from Mexico and Central America, while neighborhoods east of Haven Street such as Greektown and Joseph Lee, more "American-ized" Hispanics such as Puerto Ricans and Dominican Americans are more prevalent, moving to Baltimore from other US states. Though, all previously mentioned Hispanic groups can be found throughout Southeast Baltimore, with Highlandtown starting to act as the center of Baltimore's Hispanic community.

Argentines

editArgentines began to immigrate to Baltimore during the 1960s, most of whom were middle class.[43]

In 2011, immigrants from Argentina were the fifty-second largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Brazilians

editIn 2011, immigrants from Brazil were the thirty-fourth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

In 2019, a Brazilian cafe and grocery store opened on Eastern Avenue in Fell's Point.[44]

Chileans

editBaltimore has a small Chilean American population.[45]

In 2011, immigrants from Chile were the seventy-ninth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Colombians

editIn 2011, immigrants from Colombia were the fifty-third largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Cubans

editAt 824 people, Cuban Americans make up 0.1% of Baltimore's population, as of 2010.[46]

Cubans began arriving in Baltimore in the 1960s and were among the first Latino immigrants to the city. These early Cuban immigrants were predominantly middle-class and anti-Castro.[43]

1980 saw a second wave of immigration from Cuba. Most were outcasts, mainly poor and uneducated and many being former prisoners.[43]

In 2011, immigrants from Cuba were the sixty-third largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Dominicans

editAt, 1,111 people, Dominican Americans made up 0.2% of Baltimore's population.[47]

In 2011, immigrants from the Dominican Republic were the thirteenth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Ecuadorians

editThere are approximately 1,000 Ecuadorian Americans living in Baltimore.[48]

In 2011, immigrants from Ecuador were the twelfth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Guatemalans

editDuring the mid-1980s, many Guatemalans fled to Baltimore in order to escape the Guatemalan Civil War.[43] Most are settling in the inner neighborhoods of Southeast Baltimore.

In 2011, immigrants from Guatemala were the eleventh largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Mexicans

editAt 7,855 people, Mexican Americans made up 1.3% of Baltimore's total population and 26.7% of Baltimore's Hispanic/Latino population, as of 2010.[46][49]

Baltimore had a Mexican population of 2,999 in 2000.[50] Between 2000 and 2010, the Mexican population grew very rapidly, with an increase of over 5,000 within the decade. However, between 2010 and 2013, the Mexican population grew at a slower rate.

Recent 2013 estimates put the number of Mexicans in Baltimore at 8,012, an increase of 200 since 2010.[51] In 2011, immigrants from Mexico were the largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Peruvians

editPeruvians first began to immigrate to Baltimore during the 1960s. Most of the immigrants from Peru were middle class.[43]

In East Baltimore there exists a chapter of the Brotherhood of the Lord of Miracles. The organization holds an annual procession which honors the Lord of Miracles, a painting of Jesus Christ from Lima, Peru. This image is venerated by Peru's Roman Catholics.[52]

In 2011, immigrants from Peru were the forty-first largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Puerto Ricans

editAs of the 2010 Census, there were 3,137 Puerto Rican Americans, up from 2,207 in 2000.[50][53] They make up 0.6% of Baltimore's total population and 16.7% of Baltimore's Hispanic/Latino population, as of 2010, and are the second-largest Hispanic group in the city.[46][49] Recent 2013 estimates, put the number of Puerto Ricans in Baltimore at 4,746.[51] Baltimore has had a small and relatively stagnant Puerto Rican population since the late 20th century. However, the city's Puerto Rican community is starting to grow at a faster rate, with an increase of 900 between 2000 and 2010, and an increase of 1,600 between 2010 and 2013. With increasing crime and unemployment in Puerto Rico, Puerto Rican migration to the US mainland has picked up significantly, with Maryland being one of the top 10 destinations.[54] Some Puerto Ricans are moving to the Baltimore area from other US states, including states like New York and New Jersey. Most are settling in the outer neighborhoods of Southeast Baltimore.

Salvadorans

editSalvadorans make up 15.9% of Baltimore's Latino population.[49]

During the mid-1980s, many Salvadorans fled to Baltimore in order to escape the Salvadoran Civil War.[43] Some Salvadorans and other Hispanics are moving to Baltimore from Virginia and the DC Metropolitan area because of looser immigration restrictions.[55] Most are settling in the inner neighborhoods of Southeast Baltimore.

In 2011, immigrants from El Salvador were the fourth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore, after Mexicans, Jamaicans, and Trinidadians and Tobagonians, making Salvadorans the third-largest Hispanic/Latino immigrant population in the city, after Mexicans and Puerto Ricans.[15]

Spaniards

editDuring the 1920s many Spanish Americans settled in Highlandtown, alongside many Greek Americans.[56]

In 2011, immigrants from Spain were the seventy-fourth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Jews

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2012) |

Northern Americans

editNorthern Americans in Baltimore are residents who were born in or have ancestors from Bermuda, Canada, Greenland, Saint Pierre and Miquelon, or the United States.

In 2000, 525 Northern American-born immigrants lived in Baltimore, comprising 1.8% of all foreign-born residents of the city. This made Northern America the second smallest region of origin for immigrants after Oceania.[27]

Per data published in September 2014, 751 Northern American immigrants lived in Baltimore, making Northern America the second smallest region of origin for immigrants after Oceania.[15]

Americans

editIn the 2000 United States Census 129,568 Baltimoreans, 5.1% of the city, identify with the census category "United States or American".[13]

Appalachians

editBaltimore has a significant Appalachian population. The Appalachian community has historically been centered in the neighborhoods of Hampden, Pigtown, Remington, Woodberry, and Druid Hill Park. The culture of Baltimore has been profoundly influenced by Appalachian culture, dialect, folk traditions, and music. People of Appalachian heritage may be of any race or religion. Most Appalachian people in Baltimore are white or African-American, though some are Native American or from other ethnic backgrounds. A migration of White Southerners from Appalachia occurred from the 1920s to the 1960s, alongside a large-scale migration of African-Americans from the Deep South and migration of Native Americans from the Southeast such as the Lumbee and the Cherokee. These out-migrations caused the heritage of Baltimore to be deeply influenced by Appalachian and Southern cultures.[57]

Native Americans

editIn the 2000 United States Census, there were 6,976 Native Americans in the Baltimore metropolitan area, making up 0.3% of the area's population.[13] The majority of the Native Americans living in Baltimore belong to the Lumbee, Piscataway tribe, and Cherokee tribes. The Lumbee are originally from North Carolina, where they are concentrated in Robeson County. During the early and mid-20th century, the same wave of migration that brought large numbers of African Americans from the Deep South and poor White people from Appalachia also brought many people from the Lumbee tribe. The Baltimore American Indian Center was established in 1968 in order to serve the needs of this community. In 2011 the center established a Native American heritage museum, including exhibits on Lumbee art and culture.[58] The urban Lumbee and other Native Americans in Baltimore are concentrated in the 6 blocks around Baltimore Street in East Baltimore.[59]

Canadians

editIn 1880, Canadians made up a small portion of the foreign-born population of Baltimore at 3.6% of all foreign born residents. 16.9% (56,354) of Baltimore was foreign born, 20,287 of them Canadian.[60]

In 1940, 1,310 immigrants from Canada lived in Baltimore. These immigrants comprised 2.1% of the city's foreign-born White population.[61] In total, 2,972 people of Canadian birth or descent lived in the city, comprising 2.1% of the foreign-stock White population.[62]

In the 1960 United States Census, Baltimore was home to 2,972 Canadians.[63]

In 2011, immigrants from Canada were the fourteenth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

French Canadians and Acadians

editAt 10,494, French Canadian Americans made up 0.3% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population.[13]

Many Acadians in Baltimore are descendants of Acadian refugees that settled in the city.[64]

Romani

editThe Romani people (pejoratively known as "Gypsies") maintain a small community in Baltimore. The Romani began to immigrate to Baltimore in the late 1800s. Many of Baltimore's Romani families immigrated from Kosovo, Hungary, and Spain.[65]

The state of Maryland virtually outlawed the Romani in the 1920s, with Baltimore following suit in the 1930s. These laws banned fortune-telling for profit and levied a $1,000 entry fee for all nomads entering Baltimore. After the Baltimore law was passed, The Baltimore Sun published a headline titled "Gypsy horde leaves Maryland for good." The law was sparsely enforced and the Romani people returned to the city two years later. Discrimination against the Romani was justified by portraying the Romani as unsanitary, a threat to organized labor, and a police nuisance.[66]

In 1968, unsuccessful efforts were made to study and educate the Romani community in Baltimore. A Romani "forosko baro" (community leader) from Baltimore named Stanley Stevens tried to establish a school for Romani children. It was determined that a survey of the Romani population was necessary in order to gauge the number of Romani children. The survey was unsatisfactory since most Romani people refused to take part, with only members of Stevens' extended family expressed interest. The Stevens clan is the largest Romani clan in the city. Nonetheless, a decision was made to proceed with the plans for a school and $14,300 was raised for its construction. The school was built and provided bilingual instruction in both the English and Romani languages.[66]

A Maryland state law required all Romani people to register as Romani, a law which was only repealed in 1976, when The Baltimore Sun ran an article titled "Senators fear gypsy no longer." By the 1990s, Baltimore's Romani community still reported discrimination after over a hundred years of living in the city, though many Romani have largely assimilated into the dominant culture and now own property and live settled lives. The community numbered around 200 individuals in 1994. Records show that 6 generations of Romani are interred at Baltimore's Western Cemetery.[67]

Oceanians

editOceanians in Baltimore are residents of the city who were born in or have ancestors from Oceania, which includes Australia, New Zealand, and the Pacific Islands.

In 2000, 136 Oceanian-born immigrants lived in Baltimore, comprising 0.5% of all foreign-born residents of the city. This made Oceania the smallest region of origin for immigrants.[27]

Per data published in September 2014, 188 Oceanian immigrants lived in Baltimore, making Oceania the smallest region of origin for immigrants.[15]

Australians

editIn 2011, immigrants from Australia were the sixtieth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

New Zealanders

editIn 2011, immigrants from New Zealand were the sixty-first largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Pacific Islanders

editThere are few Pacific Islanders in Baltimore. In 2000 the Pacific Islander community only numbered 1,028 people, less than 1% of the city's population. In the same year speakers of Pacific Island languages were the twentieth largest group of language speakers in the city.[13]

Fijians

editIn 2011, immigrants from Fiji were the one hundred and fourteenth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Native Hawaiians

editThe Native Hawaiian community in Baltimore is small and numbers only 285 people as of the year 2000.[13]

Guamanians or Chamorro

editIn 2000, the Guamanian and Chamorro community in Baltimore is very small, numbering only 292 people.[13]

Samoans

editIn 2000, the tiny Samoan community in Baltimore numbers only 180 people.[13]

West Indians

editThere were 17,141 West Indian Americans in the Baltimore metropolitan area in 2000. This count excludes Caribbean people from Hispanic countries, such as Puerto Rico, the Dominican Republic, and Cuba, however, if included the Caribbean population would be about 23,000.[13] In the same year Baltimore's West Indian population was 6,597, 1% of the city's population.[27]

In 1994, there were 30,000 West Indians in the Greater Baltimore area.[68]

An annual Baltimore Caribbean Carnival Festival is held in Druid Hill Park. The festival attracts around 20–25,000 people and includes food, music, and a parade.[69][70] The event has been held since 1981 when it was formed by the West Indian Association of Maryland, an organization for people of West Indian or Guyanese descent.[71]

By proclamation of Baltimore Mayor Kurt L. Schmoke, September 10–12 have been designated as "West Indian/Caribbean Days".[71]

In 2011, Jamaicans, Trinidadians and Tobagonians, and Haitians were the largest non-Hispanic Caribbean populations. Immigrants from the West Indies not otherwise specified were the sixty-eighth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore. (Several specific West Indian countries of birth were separately listed.)[15]

Guyanese

editIn 2011, immigrants from Guyana were the twenty-first largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15] Guyanese Baltimore residents are predominantly of African descent with significant Indo-Guyanese of Bhojpuri and Tamil descent residing in the city as well. Guyanese heritage is often celebrated in Baltimore's numerous West Indian heritage parades.

Haitians

editDuring the time of the French Revolution, there was a slave revolt on the French colony of Saint-Domingue, in what is now Haiti. Many French-speaking Black Catholic and white French Catholic refugees from San Domingo left for Baltimore. In total, 1,500 Franco-Haitians fled the island.[32] The Haitian refugee population was multiracial and included white French-Haitians and their Afro-Haitian slaves, as well as many free people of color, some of whom were also slaveowners.[72] Along with the Sulpician Fathers, these refugees founded St. Francis Xavier Church. The church is the oldest historically Black Catholic church in the United States.[73]

During the Haitian Revolution, Baltimore passed an ordinance declaring that all slaves imported from the West Indies, including Haiti, were "dangerous to the peace and welfare of the city" and ordered slaveowners to banish them.[74]

In 2011, immigrants from Haiti were the thirty-seventh largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

The Baltimore-based Komite Ayiti (Haitian Creole for “Haiti Committee”) is a Haitian-American organization with around 200 members in Maryland. Komite Ayiti hosts monthly get-togethers where members can learn to speak Haitian Creole and can express their Haitian culture, including Haitian dance and cuisine. The committee was opposed to and joined in demonstrations against the Trump administration's decision to cancel temporary protected status for nearly 60,000 Haitians living in the United States.[75] The committee also celebrates an annual Haitian Independence Day event where traditional dishes such as soup joumou are served.[76]

Jamaicans

editJamaican Americans are the largest West Indian group in Baltimore,[77] making up 1% of the city's population in 2000.[78] Many Jamaicans have settled in the Park Heights neighborhood. The northern portion of the neighborhood is predominantly Jewish and the lower portion is predominantly African-American. The Jamaicans, the majority of whom are Black, have mostly settled in the lower portion of the neighborhood with other people of African descent.[79]

In 2011, immigrants from Jamaica were the second largest foreign-born population in Baltimore, after Mexicans.[15]

Trinidadians and Tobagonians

editBaltimore has a growing Trinidadian and Tobagonian population. They constitute the second largest West Indian population in Baltimore, after Jamaicans. The Trinidadians have established the Trinidad and Tobago Association of Baltimore and multiple Trinidadian businesses, including barbershops, groceries, and specialty stores. A newspaper called Caribbean Focus exists which caters to the community. Every year a festival is held to celebrate the culture of Trinidad and Tobago.[77]

In 2011, immigrants from Trinidad and Tobago were the third largest foreign-born population in Baltimore, after Mexicans and Jamaicans.[15]

White Americans

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2012) |

Close to a third of Baltimore is White according to the U.S. Census Bureau. At 201,566 people, they constitute 30.96% of the city's population.[11]

European Americans

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2012) |

White people in Baltimore are predominantly non-Hispanic people of European descent. Some of the larger European ethnic groups in Baltimore include Germans, the Irish, the English, Eastern Europeans, Italians, the French, and Greeks.

In 2000, 7,214 European-born immigrants lived in Baltimore, comprising 24.3% of all foreign-born residents of the city. This made Europe the third largest region of origin for immigrants after Latin America and Asia.[27]

Per data published in September 2014, 6,262 European immigrants lived in Baltimore, making Europe the fourth largest region of origin for immigrants after Latin America, Asia, and Africa. In 2011, the European languages spoken in Baltimore by people who spoke English "less than very well" included Spanish, French, German, Greek, Russian, Polish, various Slavic languages, Portuguese, Hungarian, Yiddish, various Scandinavian languages, and Serbo-Croatian.[15]

Albanians

editIn the 1920 census, there was only one foreign-born White person in the city of Baltimore who spoke the Albanian language as their mother tongue.[80]

In 2011, immigrants from Albania were the one hundred and fifteenth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Austrians

editIt is difficult to determine how many people in Baltimore are of Austrian descent. During the 1800s, the Austrian Empire and later Austria-Hungary included many countries that are now independent, including Austria, Hungary, the Czech Republic, Slovakia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Slovenia, large portions of Serbia and Romania, and small parts of Italy, Montenegro, Poland, and Ukraine. Though many immigrants from the Austro-Hungarian Empire belonged to a wide variety of ethnic and national groups, immigrants from the Empire were classified as "Austrians" by the United States Census Bureau up until 1881. Because of this, it is also difficult to know an accurate count for immigrant groups such as Czechs and Slovaks before that time.[81] Furthermore, most Austrians who immigrated to the U.S. traveled first through Germany to reach the Port of Bremen, where they would embark on Norddeutscher Lloyd ships to Baltimore. Because of this, many Austrians were recorded as Germans in the census records.[82] Many of these Austrians settled in the immigrant neighborhood of Locust Point.[83]

In 1940, 1,984 immigrants from Austria lived in Baltimore. These immigrants comprised 3.3% of the city's foreign-born White population.[84] In total, 2,972 people of Austrian birth or descent lived in the city, comprising 2.9% of the foreign-stock White population.[85]

In the 1960 United States Census, Baltimore was home to 4,031 Austrians.[63]

In 2011, immigrants from Austria were the ninety-eighth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Belarusians

editImmigrants from Belarus established the Transfiguration of our Lord Russian Orthodox Church in 1963 in order to serve the needs of the Russian Orthodox community.[citation needed]

Kaskad (Cascade) is a Russian language newspaper founded by a Jewish immigrant from Belarus. The newspaper is aimed at the Russian-speaking community of immigrants from Russia, Belarus, and other Russian-speaking areas. Many of the readers are Jewish immigrants from the former Soviet Union.[86][87]

In 2011, immigrants from Belarus were the seventy-eighth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

British

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2012) |

The British people in Baltimore include people of English, Cornish, Scotch-Irish, Scottish, and Welsh descent.

In 1940, 3,428 immigrants from the United Kingdom lived in Baltimore. These immigrants comprised 5.6% of the city's foreign-born White population.[88] In total, 8,322 people of British birth or descent lived in the city, comprising 6% of the foreign-stock White population.[89]

In the 1960 United States Census, Baltimore was home to 8,322 Brits.[63]

In 2011, immigrants from the United Kingdom were the nineteenth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

English

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2012) |

The English were the first European settlers in Maryland.

In 1880, English and Scottish Americans made up a small portion of the foreign-born population of Baltimore at 5% of all foreign born residents. 16.9% (56,354) of Baltimore was foreign born, 2,817 of them either English or Scottish.[60]

At 235,352 people in 2000, English Americans made up 9.2% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population. This made them the third largest European ethnic group in the Baltimore area after the Germans and the Irish.[13] In the same year Baltimore's English population was 21,015, 3.2% of the city's population.[27]

In 2011, immigrants from England were the thirty-ninth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Scotch-Irish

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2014) |

At 32,755 people, Scotch-Irish Americans made up 1.3% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population.[13] In the same year Baltimore city's Scotch-Irish population was 3,274, 0.5% of the city's population.[27]

Scottish

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (October 2012) |

In 1880, Scottish and English Americans made up a small portion of the foreign-born population of Baltimore at 5% of all foreign born residents. 16.9% (56,354) of Baltimore was foreign born, 2,817 of them either Scottish or English.[60]

At 42,728 people, Scottish Americans made up 1.7% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population.[13] In the same year Baltimore city's Scottish population was 4,306, 0.7% of the city's population.[27]

Many Scots settled in the immigrant neighborhood of Locust Point.[83]

In 2011, immigrants from Scotland were the ninetieth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Welsh

editAt 19,776 people, Welsh Americans made up 0.8% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population in 2000.[13] In the same year Baltimore city's Welsh population was 2,137, 0.3% of the city's population.[27]

Welsh immigrants, primarily from workers from South Wales, began settling in Baltimore in large numbers beginning in the 1820s. Welsh and Irish migrant workers composed a large portion of Baltimore's working class during the early and mid-1800s.[90] In 1850, a large community of copper workers from Wales settled in the neighborhood of Canton.[91] These workers established a Presbyterian church in 1865, located on Toone Street in Canton.[92]

Other Welsh people who came to the city settled in the immigrant neighborhood of Locust Point.[83]

Belgians

editIn 2011, immigrants from Belgium were the fifty-first largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Bulgarians

editIn 1920, 26 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Bulgarian language as their mother tongue.[80]

Cypriots

editBaltimore has a significant Cypriot American population.[93]

Czechs

editThe Czech presence in Baltimore dates back to the mid-19th century. The Czech community numbered 17,798 in 2000, making up 0.7% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population.[13]

The history of the Czechs in Baltimore dates back to the mid-19th century. Thousands of Czechs immigrated to East Baltimore during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, becoming an important component of Baltimore's ethnic and cultural heritage. The Czech community has founded a number of cultural associations and organizations to preserve the city's Czech heritage, including a Roman Catholic church, a heritage association, a festival, a language school, and a cemetery. The population began to decline during the late 20th and early 21st centuries, as the community aged and many Czech Americans moved to the suburbs of Baltimore.

Danish

editSome of the earliest Danish settlement in the United States occurred in Baltimore, along with other Eastern Shore cities such as Boston, Philadelphia and New York City.[94]

In 1920, 236 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Danish language.[80]

The Danish American community in the Baltimore metropolitan area numbered 5,503 in 2000, making up 0.2% of the area's population.[13] In the same year Baltimore city's Danish population was 488, 0.1% of the city's population.[27]

In 2011, immigrants from Denmark were the one hundred and seventeenth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Dutch

editAt 27,754 people, Dutch Americans made up 1.1% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population in 2000.[13] In the same year Baltimore city's Dutch population was 3,024, 0.5% of the city's population.[27]

Some Baltimoreans of Dutch descent have been Dutch Jews. Dutch Jews first began to immigrate during the 1830s and 1840s. By 1850, only 2% of Baltimore's Jewish population was Dutch. Only four Dutch Jewish families and twenty-one Dutch Jewish families immigrated during the 1860s and 1870s, respectively. Although the Dutch Jewish population was small, it comprised a large portion of the city's Dutch population. In 1850, 49% of Dutch-born Baltimoreans were Jewish. However, the population of Dutch Catholics increased as they found the city to be becoming more hospitable, and so the percentage of Dutch Jews declined. By 1860, only 17% of the Dutch-born were Jewish. One-third of the Dutch Jews lived in Ward 10 in 1860 and in Ward 5 in 1870.[95]

In 1920, 181 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Dutch language or one of the Frisian languages as their mother tongue. 51 people spoke Flemish, a dialect of Dutch spoken in the Flanders region of Belgium, as their mother tongue.[80]

In 2011, immigrants from the Netherlands were the forty-seventh largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Estonians

editThe Estonian American population is small, with only around 25,000–35,000 individuals in the United States. The Baltimore–Washington Metropolitan Area has one of the largest Estonian populations in the U.S.,[96] with around 2,000 living in Maryland.[97] The Baltimore Estonian community has established a number of institutions, including St. Mark's Estonian Lutheran Church Archived 2013-02-16 at the Wayback Machine (established as the Estonian Evangelical Lutheran Church),[98] the Baltimore Estonian Society,[99] the Baltimore Estonian House, the Baltimore Estonian Supplementary School, and the Baltimore Association for the Advancement of Estonian.[100]

Finns

editThe Finnish community in Baltimore was originally centered in the Highlandtown neighborhood. During the 1930s the Finns operated Highlandtown's Finnish Hall as a community center. The Hall was also a center for union organizing by the workers of Bethlehem Steel.[101] By the year 1940, there was a Finnish community of 400 people living in the neighborhood.[32] Large numbers of Finnish Americans were involved in labor activism and struggles for workers' rights. Many of the Finnish immigrants were socialists, which led to Finnish Americans developing a reputation for radicalism.[102] In the early days of the Communist Party USA, Finnish immigrants made up 40% of the Party's membership. Reflecting this tradition of Finnish American radicalism, the Finnish Hall was a center for leftist activism in Baltimore.[103]

In 1920, 110 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Finnish language as their mother tongue.[80]

French

editIn the 2000 United States Census the French American community in Baltimore numbered 47,234 (1.9% of Baltimore's population) and an additional 10,494 (0.4%) identified as French Canadian American. This places Baltimore's total population of French descent at 57,728, which is 2.3% of Baltimore's population.[13] The Census also found that the French language (including French Creole) is spoken at home by 5,705 people in Baltimore.[30]

The French community in Baltimore dates back to the 18th century. The earliest wave of French immigration began in the mid-1700s, bringing many Acadian refugees from Canada's Maritime Provinces. The Acadians were exiled from Canada by the British during the French and Indian War. Later waves of French settlement in Baltimore from the 1790s to the early 1800s brought Roman Catholic refugees of the French Revolution and refugees of the Haitian Revolution from the French colony of Saint-Domingue.[citation needed]

French Canadians

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (May 2014) |

At 10,494, French Canadian Americans make up 0.3% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population.[13]

Many French-Canadians in Baltimore are descendants of Acadian refugees from Canada's Maritime Provinces that settled in the city during the mid-1700s.[64]

Germans

editThe first Germans began to immigrate to Baltimore in the 17th century. During the 1800s, the Port of Baltimore was the second-leading port of entry for immigrants, after Ellis Island in New York City. Many Germans immigrated to Baltimore during this time.[104] In 2000, the German population made up 18.7% of Baltimore's population, with 478,646 people of German descent living in Baltimore. This makes the Germans the largest European population in the city.[13]

Greeks

editThe first Greeks in Baltimore were nine young boys who arrived as refugees of the Chios Massacre, the slaughter of tens of thousands of Greeks on the island of Chios at the hands of the Ottomans during the Greek War of Independence.[32] However, Greek immigration to Baltimore did not begin in significant numbers until the 1890s. Early Greek settlers established the Greek Orthodox Church "Evangelismos" in 1906 and the Greek Orthodox Cathedral of the Annunciation in 1909.[105] By the 1920s, a vibrant yet small Greek community had been firmly established. The peak of the Greek migration to Baltimore was between the 1930s and the 1950s.[106]

The Greek population saw another smaller surge in numbers after the passage of the Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965, which allowed for the immigration of thousands of Greeks. This wave of Greek immigrants to Baltimore ended by the early 1980s. During the 1980s the Greek residents of the neighborhood that was then known simply as the Hill successfully petitioned the city government to rename the neighborhood as Greektown. By that time the Greek community was 25,000 strong.[107]

Hungarians

editAt 11,076 people, Hungarian Americans make up 0.4% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population in 2000.[13] In the same year Baltimore city's Hungarian population was 1,245, 0.2% of the city's population.[27]

Hungarians first began to immigrate to Baltimore during the 1880s, along with other Eastern Europeans.[108] They tended to embark from Bremen, Germany and then settle in the neighborhood of Locust Point, alongside other European immigrants.[83] Hungarians, alongside other Eastern European immigrants, worked in steel mills, shipyards, canneries, and garment factories.[109]

In 1920, 600 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Hungarian language as their mother tongue.[80]

In the 1930 United States Census, there were fewer than 1,000 Hungarian-born people in Baltimore.[32]

In the 1960 United States Census, Baltimore was home to 1,867 Hungarians.[63]

In 2011, immigrants from Hungary were the seventy-third largest foreign-born population in Baltimore and the Hungarian language was twenty-third most commonly spoken language among people who spoke English "less than very well".[15]

Irish

editAt 341,683 people as of 2000, Irish Americans made up 13.4% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population. This made them the second largest European ethnic group in the Baltimore area after the Germans.[13] In the same year Baltimore city's Irish population was 39,045, 6% of the city's population.[27]

In 1940, 2,159 immigrants from Ireland lived in Baltimore. These immigrants comprised 3.5% of the city's foreign-born White population.[110] In total, 4,077 people of Irish birth or descent lived in the city, comprising 4.6% of the foreign-stock White population.[111]

In 2011, immigrants from Ireland were the sixty-sixth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Italians

editItalians began to settle in Baltimore during the late 1800s. Some Italians immigrants came to the Port of Baltimore by boat. The earliest Italian settlers in Baltimore were sailors from Genoa, the capital city of the Italian region of Liguria. Later immigrants came from Naples, Abruzzo, Cefalù, and Palermo. These immigrants created the monument to Christopher Columbus in Druid Hill Park.[112] Many other Italians came by train after entering the country through New York City's Ellis Island. The Italian immigrants who arrived by train would enter the city through the President Street Station. Because of this, the Italians largely settled in a nearby neighborhood that is now known as Little Italy.

Little Italy comprises 6 blocks bounded by Pratt Street to the North, the Inner Harbor to the South, Eden Street to the East, and President Street to the West. Other neighborhoods were large numbers of Italians settled include Lexington, Belair-Edison, and Cross Street. Many settled along Lombard Street, which was named after the Italian town of Guardia Lombardi. The Italian community, overwhelmingly Roman Catholic, established a number of Italian-American parishes such as St. Leo's Church and Our Lady of Pompeii Church. The Our Lady of Pompeii Church holds the annual Highlandtown Wine Festival, which celebrates Italian-American culture and benefits the Highlandtown community association.[113]

In 1920, 7,930 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Italian language.[80]

In 2011, immigrants from Italy were the thirty-sixth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

In 2013, an estimated 16,581 Italian-Americans resided in Baltimore city, 2.7% of the population.[114]

Latvians

editThe Latvian community in Maryland in very small and makes up less than 2,000 people.[97]

In 1920, 2,554 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke either the Latvian language or the Lithuanian language as their mother tongue.[80]

In 2011, immigrants from Latvia were the eighty-ninth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Lithuanians

editThe Lithuanians began to settle in Baltimore in 1876.[32] The wave increased greatly during the 1880s and continued in large numbers until the 1920s. By 1950, the Lithuanian community numbered around 9,000.[32] The Lithuanians largely settled in a neighborhood north of Hollins Street that became known as Baltimore's Little Lithuania.[115] A few remnants of the neighborhood's Lithuanian heritage still remain, such as Lithuanian Hall located on Hollins Street.[116][117]

Three Roman Catholic churches have been designated as Lithuanian parishes: St. Alphonsus' beginning in 1917, St. John the Baptist Church from 1888 to 1917, and St. Wenceslaus beginning in 1872. St. Alphonsus' is the only remaining Lithuanian parish in Baltimore, as St. Wenceslaus was re-designated as a Bohemian parish and St. John the Baptist Church closed in 1989.[118] While most Lithuanians who settled in Baltimore were Roman Catholic, a large minority were Lithuanian Jews. The Yeshivas Ner Yisroel, a prominent yeshiva in Baltimore, was founded as a Lithuanian (Litvish)-style Talmudic college by Jews from Lithuania and Belarus.

Moldovans

editIn 2011, immigrants from Moldova were the one hundred and first largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Norwegians

editThe majority of the Norwegian immigrants to Baltimore worked in the shipping industry. The Baltimore chapter of the Sons of Norway, Lodge Nordkap, No. 215, was established in 1921 and is now located in Freeland, Maryland. These settlers also established the Norwegian American Club of Maryland.[119]

The peak of Norwegian immigration to Baltimore was in 1937, when 315 Norwegian ships arrived in the city and around 13,000 Norwegian immigrants stayed at the Norwegian Seamen's Church and lodging house that was located on South Broadway. The lodging house and church offered Norwegian language newspapers and Norwegian cuisine to the visitors. Many of the Norwegian seamen stayed in Baltimore and worked as factory engineers and ship chandlers.[120]

In 1920, 419 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Norwegian language as their mother tongue.[80]

In the 1960 United States Census, Baltimore was home to 749 Norwegians.[63]

Norwegian Americans in Baltimore numbered 12,481 in 2000, making up 0.5% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population.[13] In the same year Baltimore city's Norwegian population was 1,347, 0.2% of the city's population.[27]

In 2011, immigrants from Norway were the one hundred and fourth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Poles

editPolish Americans in Baltimore numbered 122,814 in 2000, making up 4.8% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population. They were the fifth largest European ethnic group in the city.[13]

The Polish community is largely centered in the neighborhoods of Canton, Fell's Point, Locust Point, and Highlandtown. The first Polish immigrants to Baltimore settled in the Fell's Point neighborhood in 1868. Polish mass immigration to Baltimore and other U.S. cities first started around 1870, many of whom were fleeing the Franco-Prussian War.[121]

Many of the Polish immigrants came from agricultural regions of Poland and were often considered unskilled workers. Many worked as stevedores for Baltimore's International Longshoremen's Association. Other Polish immigrants worked in the canneries, some travelling to the Gulf Coast of Louisiana and Mississippi to work in the seafood canneries during the winter months. After the abolition of slavery, farmers had lost their slaves and wanted a cheap source of labor. Following changes in U.S. immigration laws many Central and Eastern European migrants, particularly Polish and Czech, came to Maryland to fill this need.[122]

Portuguese

editAt 3,316 people, Portuguese Americans made up 0.1% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population in 2000.[13] In the same year Baltimore city's Portuguese population was 310, 0.0% of the city's population.[27]

Very few Portuguese Jews have settled in Baltimore. The city's small Portuguese-Jewish community founded the Sefardic Congregation Beth Israel in 1856, but the synagogue closed after two years due to low attendance.[123]

In 1920, 33 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Portuguese language as their mother tongue.[80]

In 2011, immigrants from Portugal were the one hundred and eleventh largest foreign-born population in Baltimore and the Portuguese language (including Portuguese Creole) was the twenty-second most commonly spoken language of people who spoke English "less than very well".[15]

Romanians

editNative-born and immigrant Romanians in the city formed communities in East Baltimore, alongside other Eastern Europeans.[124]

In 1920, 200 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Romanian language as their mother tongue.[80]

In the 1930 United States Census, there were fewer than 1,000 Romanian-born people in Baltimore.[32]

Some Romanian immigrants to Baltimore have been Romanian Jews. The Rumanian Relief Committee and the Industrial Removal Office (IRO) helped resettle Romanian Jews in the United States. As a result of this program, some of the Romanian Jews settled in Baltimore.[citation needed]

In 2011, immigrants from Romania were the fifty-seventh largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

At one time the most powerful Romani clan in Baltimore was the Stevens clan of Romanian gypsies. Hundreds of Stevenses immigrated from Romania to Baltimore during the late 1800s.[125]

Russians

editThe Russian community in the Baltimore metropolitan area numbered 35,763 in 2000, making up 1.4% of the area's population.[13] Russian-Americans are the largest foreign-born groups in Baltimore.[126] According to the 2000 Census, the Russian language is spoken at home by 1,235 people in Baltimore.[30]

While a minority of immigrants from Russia to Baltimore have been ethnic Russian Christians, the majority have been Russian Jews. In the 1930 United States Census there were 17,000 Russian immigrants living in the city, most of whom were Jewish.[32] In comparison to Baltimore's wealthy and assimilated German Jews, the Russian Jews historically were largely poor and lived in slums with other Russian Americans. Baltimore's Russian community, including the Russian Jews, was originally centered in Southeast Baltimore.[127] The largest wave of Russian-Jewish immigrants to Baltimore occurred during the 1880s. A second large wave of Russian-Jewish immigrants came during the 1990s, following the collapse of the Soviet Union.[128]

Rusyns

editWhile many immigrants from Western Ukraine identify simply as Ukrainian Americans, others identify as Rusyn American. Rusyns also sometimes describe themselves as Ruthenians. A number of the Western Ukrainians that established St. Michael the Archangel Ukrainian Catholic Church identified as Rusyns. Rusyns also helped establish Sts. Peter & Paul Ukrainian Catholic Church.[citation needed]

In 1920, 151 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Ruthenian language as their mother tongue.[80]

Serbs

editIn 1999, the Serbian American community in Baltimore was very small. At the time, only about 400 Serbian families were scattered between Baltimore and Richmond, Virginia.[129]

In 1920, 261 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Serbo-Croatian language as their mother tongue.[80]

In 2011, immigrants from Serbia were the ninety-third largest foreign-born population in Baltimore and the Serbo-Croatian language was the thirty-first most commonly spoken language in the city among people who spoke English "less than very well".[15]

Slovaks

editAt 6,077 people, Slovak Americans made up 0.2% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population in 2000.[13] In the same year Baltimore's Slovak population was 536, 0.11% of the city's population.[27]

Many Slovak immigrants to the city settled in East Baltimore along with Czechs and other Slavic ethnic groups. However, many Slovaks have since migrated to the suburbs, particularly in Anne Arundel and Harford County.[130]

Slovaks, along with Czechs, established the Bohemian National Cemetery of Baltimore and the Grand Lodge Č.S.P.S. of Baltimore.

An annual Czech and Slovak Heritage Festival exists and is held in Baltimore's suburb of Parkville.[131][132]

In 1920, 402 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Slovak language as their mother tongue.[80]

In 2011, immigrants from Slovakia were the fifty-ninth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Slovenes

editIn 1920, 134 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Slovenian language as their mother tongue.[80] Most Slovenes were documented as Austrian or Slavic once they reached Ellis Island.

Spaniards

editDuring the 1920s many Spanish Americans settled in Highlandtown, alongside many Greek Americans.[56]

In 2011, immigrants from Spain were the seventy-fourth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Swedes

editAt 14,598 people, Swedish Americans make up 0.6% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population in 2000.[13]

Many Swedes settled in the immigrant neighborhood of Locust Point.[83]

In 1920, 419 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Swedish language as their mother tongue.[80]

In the 1960 United States Census, Baltimore was home to 778 Swedes.[63]

In 2011, immigrants from Sweden were the one hundred and thirteenth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Swiss

editSwiss immigrants to Baltimore were primarily Swiss of German descent. Many of the Swiss immigrants belonged to radical Anabaptist sects such as the Amish and the Mennonites. Many of the Mennonites and Amish that settled in Baltimore were originally Pennsylvania Dutch.[32] Other German migrants from Pennsylvania were Lutheran; the Zion Lutheran Church built in 1755 had a large number of Pennsylvania Dutch members.

In 2011, immigrants from Switzerland were the eightieth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Ukrainians

editUkrainians began settling in Baltimore during the 1880s, settling mostly in East Baltimore and Southeast Baltimore, especially in the Highlandtown neighborhood.[32] Most of these immigrants came from Western Ukraine and were Catholic. By the 1890s, Ukrainian Catholic priests were traveling from Pennsylvania to Baltimore to serve the Ukrainian Catholic community. St. Michael the Archangel Ukrainian Catholic Church was founded as a parish in 1893 and the church was built in 1912, though construction took nearly a century to complete.[133]

Middle Eastern and North African people

editMost people of Middle Eastern or North African origin in Baltimore are Arabs or Iranians. There are also Turkish and Israeli populations.

In 2011, Middle Eastern languages spoken in Baltimore included Arabic, Persian, and Hebrew.[15]

Arabs

editAt 7,897 people, Arab Americans make up 0.3% of the Baltimore metropolitan area's population in 2000.[13] In the same year Baltimore city's Arab population was 1,298, 0.2% of the city's population.[27]

In 1920, 29 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Syriac or Arabic languages as their mother tongue.[80]

In 2011, the Arabic language was the seventh most common language in Baltimore among people who spoke English "less than very well".[15]

During the 2015 Baltimore protests, the Bloods gang allegedly protected Black-owned stores by directing rioters to loot and vandalize Arab-owned stores instead.[36]

Egyptians

editAn Egyptian American community exists in southeastern Baltimore, especially in Highlandtown. Other Egyptians live in eastern Baltimore County, mainly in Dundalk. Many Egyptians first immigrate to New York City, then resettle in the Baltimore area due to more job opportunities and a lower cost of living.[134]

In 2011, immigrants from Egypt were the thirty-eighth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Jordanians

editIn 2011, immigrants from Jordan were the one-hundred and eighth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Lebanese

editIn 2011, immigrants from Lebanon were the ninety-sixth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Moroccans

editIn 2011, immigrants from Morocco were the sixty-fourth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Syrians

editIranians

editIranian-Americans hold an annual festival, the Chaharshanbe Suri (Festival of Fire), as part of their celebration of the Iranian New Year (known as Nowruz). The event is held at Oregon Ridge Park in Cockeysville, a suburb of Baltimore.[135]

After the Iranian Revolution in 1978, many Persian Jews fled the country and immigrated to Baltimore.[136] More arrived during the 1980s.[137] In 2009, Iranian Jews established a Persian-style Sephardic synagogue in Baltimore.[138]

In 2011, immigrants from Iran were the thirty-first largest foreign-born population in Baltimore and the Persian language was the eighteenth most common language among people who spoke English "less than very well".[15]

Israelis

editIn 2011, immigrants from Israel were the forty-eighth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

In 1920, 19,320 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke either the Hebrew language or the Yiddish language as their mother tongue.[80]

In 2011, the Hebrew language was the thirty-second most common in Baltimore among people who spoke English "less than very well".[15]

Turks

editIn 1920, 8 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Turkish language as their mother tongue.[80]

In 2011, immigrants from Turkey were the eighty-seventh largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

West Asian and Central Asian people

editArmenians

editIn 1920, 29 foreign-born White people in Baltimore spoke the Armenian language as their mother tongue.[80]

In 2011, immigrants from Armenia were the one hundred and third largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Kazakhstanis

editIn 2011, immigrants from Kazakhstan were the eighty-sixth largest foreign-born population in Baltimore.[15]

Demographics

edit| Ethnic group | 2000 | Percentage | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total population | 651,154 | |||||||||

| African Americans | 417,009 | 64.04 | ||||||||

| Whites | 201,566 | 30.96 | ||||||||

| Hispanics | 11,061 | 1.70 | ||||||||

| Asian Americans | 9,824 | 1.51 | ||||||||

| Other | 11,694 | 1.80 | ||||||||

| Population by Race in Baltimore Maryland (2010) | ||

| Race | Population | % of Total |

|---|---|---|

| Total | 620,961 | 100 |

| African American | 395,781 | 63 |

| White | 183,830 | 29 |

| Asian | 14,548 | 2 |

| Two or More Races | 12,955 | 2 |

| Other | 11,303 | 1 |

| American Indian | 2,270 | < 1% |

| Three or more races | 1,402 | < 1% |

| Native Hawaiian Pacific Islander | 274 | < 1% |

| Source: 2010 Census via Maryland Department of Planning[139] | ||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Then & Now: Essay". Baltimore Magazine. 20 May 2014. Retrieved 2019-05-11.

- ^ Akerson, Louise A. (1988). American Indians in the Baltimore area. Baltimore, Maryland: Baltimore Center for Urban Archaeology (Md.). p. 15. OCLC 18473413.

- ^ Potter, Stephen R. (1993). Commoners, Tribute, and Chiefs: The Development of Algonquian Culture in the Potomac Valley. Charlottesville, Virginia: University of Virginia Press. p. 119. ISBN 0-8139-1422-1. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ^ A Point of Natural Origin Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine and Locust Point – Celebrating 300 Years of a Historic Community Archived 2007-09-29 at the Wayback Machine, Scott Sheads, Mylocustpoint.

- ^ "Ghosts of industrial heyday still haunt Baltimore's harbor, creeks". Chesapeake Bay Journal. Archived from the original on 2018-10-01. Retrieved 2012-09-08.

- ^ Also shown as "Chisupioc" (by John Smith of Jamestown) and "Chisapeack", in Algonquian "Che" means "big" or "great", "sepi" means river, and the "oc" or "ok" ending indicated something (a village, in this case) "at" that feature. "Sepi" is also found in another placename of Algonquian origin, Mississippi. The name was soon transferred by the English from the big river at that site to the big bay. Stewart, George (1945). Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States. New York: Random House. p. 23.

- ^ Farenthold, David A. (2006-12-12). "A Dead Indian Language Is Brought Back to Life". The Washington Post. p. A1. Retrieved 2007-03-19.

- ^ Murphree, Daniel Scott (2012). Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. p. 494. ISBN 978-0-313-38126-3. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ^ Wiener, Roberta; Arnold, James R. (2005). "5; Maryland's Battles - Battles with the Native Americans". Maryland: The History of Maryland Colony, 1634–1776. Chicago, Illinois: Raintree. pp. 33–5. ISBN 0-7398-6880-2. OCLC 52429938. Retrieved October 10, 2012.

- ^ Alabaster cities: urban U.S. since 1950. John R. Short (2006). Syracuse University Press. p.142. ISBN 0-8156-3105-7

- ^ a b c d "Baltimore, MD Ethnicity" ERsys.com. (Based on U.S. Census, 2000). Retrieved 12/05/14.

- ^ "Two Baltimores: The White L vs. the Black Butterfly". Baltimore City Paper. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah "Table DP-1. Profile of General Demographic Characteristics: 2000" (PDF). 2000 United States Census. Retrieved 2012-08-20.

- ^ "Rain keeps crowds at bay during annual Africa festival". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce "The Role of Immigrants in Growing Baltimore: Recommendations to Retain and Attract New Americans" (PDF). WBAL-TV. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-10-30. Retrieved 2014-10-31.

- ^ "More From Eritrea Seek Life Of Peace In Maryland". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ Medland, Mary (10 December 2013). "Ethiopian-owned businesses enliven Baltimore neighborhoods". Bmore. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "ECCB - For Ethiopians in Baltimore". Ethiopian Community Center in Baltimore. Archived from the original on 14 May 2014. Retrieved 13 May 2014.

- ^ "Little Ethiopia: What was once Baltimore's Chinatown is now home to a flurry of Ethiopian businesses". Baltimore City Paper. Retrieved 2014-05-12.

- ^ "Baltimoreans react to violence in Kenya". WBAL-TV. 23 September 2013. Retrieved 2014-11-17.

- ^ "Baltimore Liberians Mourn Loss Of Relatives To Ebola". WYPR. Retrieved 2014-10-01.

- ^ "Nigerian fest, feast beckon". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- ^ "Baltimore County, MD | Data USA". datausa.io. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ "Nigeria's Yoruba language is second most spoken foreign language in Baltimore schools". Face2Face Africa. 2019-02-12. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ Bowie, Liz. "Baltimore County schools are rapidly adding students. More than half are immigrants or speak another language". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ "Baltimore's Sudanese immigrants return to homeland to build a new nation". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Social Statistics Baltimore, Maryland". Infoplease. Retrieved 2015-05-31.

- ^ a b "Orientation program helps refugees in Baltimore". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ "Howard school system opens arms to aid Burmese refugees". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2014-05-15.

- ^ a b c d e "Immigration and the 2010 Census Governor's 2010 Census Outreach Initiatives" (PDF). Maryland State Data Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-04-07. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ^ a b c "16th-century swordplay highlights festival". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l American Guide Series (1940). Maryland: A Guide to the Old Line State. United States: Federal Writers' Project. OCLC 814094.

- ^ "Baltimore Chinatown History, University of Maryland". Archived from the original on 2011-03-12. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ^ a b Bell, Madison Smartt (2007). Charm City: A Walk Through Baltimore. New York: Crown Journeys. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-307-34206-5. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

Baltimore no Japanese.

- ^ "The 'where' of Chinatown: Rekindling its vitality has support, but site is in dispute". Archived from the original on 2014-04-24. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ^ a b Nixon, Ron (28 April 2015). "Amid Violence, Factions and Messages Converge in a Weary and Unsettled Baltimore". The New York Times. Retrieved 2015-04-30.

- ^ "Filipino festival whets appetites". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2014-05-13.

- ^ "The Demographic Statistical Atlas of the United States - Statistical Atlas". statisticalatlas.com. Retrieved 2020-10-20.

- ^ "India celebrates a deity with its 'chariot festival'". The Baltimore Sun. Retrieved 2014-05-14.

- ^ "Mappers' Delight - Northern Virginia's Korean community finally gets organized politically—about cartography". Washington City Paper. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved 2014-03-31.