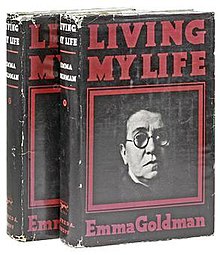

Living My Life is the autobiography of Lithuanian-born anarchist Emma Goldman, who became internationally renowned as an activist based in the United States. It was published in two volumes in 1931 (Alfred A. Knopf) and 1934 (Garden City Publishing Company). Goldman wrote it while living in Saint-Tropez, France, following her disillusionment with the Bolshevik role in the Russian Revolution.

first edition | |

| Author | Emma Goldman |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Subject | Autobiography, anarchism |

| Publisher | Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. (volume 1) Garden City Publishing Co.(volume 2) |

Publication date | 1931 (volume 1) 1934 (volume 2) |

| Publication place | United States |

| Pages | 993 |

| OCLC | 42598818 |

The text thoroughly covers her personal and political life from early childhood through to 1927. The book has constantly remained in print since, in original and abridged editions. Since the autobiography was published nine years before Goldman died in 1940, it does not record her role in the Spanish Civil War.

Background

editEmma Goldman was born in 1869 in Kovno, Lithuania (then Russian Empire). Her parents Abraham and Taube owned a modest inn but were generally impoverished. Throughout her childhood and early adolescence, Goldman traveled between her parents' home in Lithuania and her grandmother's home in Königsberg, Prussia before the family relocated to St. Petersburg. Though much of her childhood was unhappy, as her father was often abusive, Goldman was close with her older half-sister Helena and valued the modest schooling she received.

In 1885, Goldman immigrated with Helena to Rochester, New York to join their sister Lena and escape the influence of her father; he wanted to make an arranged marriage for her. Despite finding work in a clothing factory, Goldman did not stay in Rochester long. Enraged by the execution of the Haymarket bombers in 1887, she moved to New York and became one of the nation's most renowned anarchists.[1][2]

Summary

editGoldman begins Living My Life with her arrival in New York City on August 8, 1889—the day she said she began her life as an anarchist. She does not express her autobiography chronologically, as she considered her first twenty years to be something of a previous life. As Goldman recalls, "All that had happened in my life until that time was now left behind me, cast off like a worn-out garment."[3] Living My Life reflects upon Goldman's time prior to New York as a means of explaining her principles and conversion to anarchy. For instance, she describes her employment in a Rochester clothing factory as an introduction to her antagonism toward industrial labor. Goldman claimed to work ten and a half hours a day and earned $2.50 a week, not unusual for the time. After she asked the owner for a raise, she was rebuffed; she left to find work elsewhere.[4] Feeling alone in America, in 1887 Goldman "consented" to marry Jacob Kershner, a fellow Jewish immigrant. This marriage, however, would not survive long. While Goldman attributes her husband's disinterest in books and his growing interest in gambling toward their antagonism, the realization of his impotence was the breaking point for Goldman. She recalled being left in "utter bewilderment" on her wedding night. Goldman recalls being "saved from utter despair" in Rochester only by her fascination with the events at Haymarket and her subsequent move to New York City.[5]

Goldman's memoir describes her first months in New York City fondly. The book vividly describes her efforts to meet Johann Most, the notorious German anarchist and editor of the newspaper Die Freiheit. Most, after the first meeting, became her mentor. Goldman's recollections heavily imply that Most was determined to craft her into a "great speaker," one that could take his place as a leader for "the Cause." It was during her unofficial tutelage that Goldman began public speaking. Beginning first by stumping in New York City, Goldman expanded her skills and departed shortly thereafter on a lecture tour of Cleveland, Buffalo, and her family's home of Rochester.[6]

One of the key moments of Living my Life was Goldman's fateful encounter with a young Jewish anarchist named Alexander "Sasha" Berkman. The two met on Goldman's first day in New York and quickly became close friends and lovers. While Goldman credits both Most and Berkman with influencing her belief in anarchism, Living My Life positions Berkman and Most as rivals for Goldman's personal affections. Goldman recalls being courted by both men and being drawn to both in different ways:

"The charm of Most was upon me. His eagerness for life, for friendship, moved me deeply. And Berkman, too, appealed to me profoundly. His earnestness, his self-confidence, his youth—everything about him drew me with irresistible force."[7]

These thoughts were indicative of Goldman's ruminations regarding "free love--" a persistent theme throughout the memoir. Maintaining that "binding people for life was wrong," Goldman carried on romantic affairs with Berkman, but rejected the advances of Most. In reflection, Goldman determines that Most "cared for women only as females" and ultimately "broke" with her because he wanted women "who have no other interest in life but the man they love and the children they bear him."[8]

Following her break with Most, Goldman continues her work by describing her complicity in an attempt to murder Henry Clay Frick, chairman of Carnegie Steel Company, in 1892. Goldman lived with Berkman in New England when they heard news of the Homestead Strike, which had erupted at one of Carnegie's Pittsburg area steel mills. Frick's attempts to violently repress the strikers enraged Berkman and Goldman who quickly devised a plan for Frick's assassination. Living My Life describes how Goldman was motivated by the doctrine of "Propaganda by Deed" in Most's Science of Revolutionary Warfare, which supported political violence as a tool of the anarchist. She recounted her belief that Frick's death would "re-echo in the poorest hovel, would call the attention of the whole world to the real cause behind the Homestead struggle."[9] In her account, the couple agreed that Berkman would travel to Homestead and sacrifice himself for the Cause, while Goldman would remain in New York to raise funds and deliver speeches in the wake of the assassination. To demonstrate her devotion to conspiracy, Goldman details how she had even considered prostitution to raise $15 needed for Berkman's travels before agreeing to accept a loan from her sister with the pretense of her being ill.[10]

Living My Life describes the aftermath of the attempted assassination as a difficult time in Goldman's life. Berkman failed in his attempt to assassinate Frick, who survived his wounds. In fact, Berkman was not, as expected, killed after the attack but was sentenced to twenty-two years in prison. Furthermore, rather than receiving praise from her anarchist comrades, Most condemned Berkman and reversed his opinion on "Propaganda by Deed." Goldman writes that she was so infuriated by the "betrayal" of Most that she publicly horsewhipped her former mentor at a public rally. The failed assassination attempt deeply divided the anarchist movement and Goldman found herself labelled a "pariah" by supporters of Most.[11] Goldman's penchant for radicalism and inspired speaking grew in the wake of the Homestead strike and subsequently resulted in increased police attention, resulting in her arrest in Philadelphia under charges of inciting to riot in August 1893.[12]

Following a description of her year in prison and her later travels in Western Europe, the memoir examines Goldman's return to lecturing for the anarchist cause in the late 1890s. Lecturing in Cleveland in 1900, Goldman recalls being approached by a young man who gave the name "Nieman." Responding to the young man's interest in anarchist literature, she gladly gave him a reading list and thought nothing strange of the event. It was soon discovered that Nieman was the alias of Leon Czolgosz, the assassin who fatally shot President McKinley in September 1901. Goldman, implicated as an accomplice in the assassination, was arrested in Chicago. Though held in contempt by the American public and badly beaten during a prison transfer, Goldman was released due to lack of evidence.[13]

Goldman's autobiography depicts the repercussions of McKinley's assassination as long lasting and severe. Despite being acquitted of all charges, Goldman's association with Czolgosz made her a pariah to anarchist and non-anarchist alike. Despite her wrongful imprisonment, Goldman stood by Czolgosz and sought to discover his justification for the assassination. Goldman reflects that although Czolgosz's action was misguided, she "was not willing to swear away the reason, character, or life of a defenseless human being."[14] Goldman attempted to enlist anarchist support in a campaign to hire Czolgosz an attorney—in order to give him a chance to "explain his act to the world."[15] Few, however, showed willingness to associate with the assassin. Her belief in the movement was shaken. As Goldman suggests, many of her comrades had "been flaunting anarchism like a red cloth before a bull, but they had [run] to cover at its first charge."[16]

Despite these difficulties, Goldman established her own radical newspaper, Mother Earth in 1907. Throughout the following decade, Goldman describes her political associations with the recently released Alexander Berkman to protest US preparedness, political repression, restrictions on homosexuality and birth control. The memoir devotes particular attention to Goldman's view of homosexuality. Goldman writes, recalling an interaction with a woman who confessed to her feelings of "homosexuality," "To me anarchism was not a mere theory for a distant future; it was a living influence to free us from inhibitions… and from the destructive barriers that separate man from man."[17] Her increased attention as the result of these speaking engagements led to greater attention from law enforcement. Goldman was arrested under the Comstock Act following a speech on birth control in 1915, but was shortly thereafter released.[18]

Living My Life continues by discussing Goldman's efforts to counter-act military preparedness and the draft—especially the 1917 arrest of both Goldman and Berkman. The two were arrested on charges of encouraging men to avoid conscription into the army. inspired by anti-War sentiment in the United States, Goldman and Berkman focused significant attention to anti-conscription articles in Mother Earth and held several anti-preparedness rallies. Following an unsuccessful appeal to the Supreme Court, the couple was sentenced to two years in prison and forced to pay a ten thousand dollar fine.[19]

The autobiography concludes with Goldman's exile in the Soviet Union. After serving their full sentences, both Goldman and Berkman were released in the midst of the first Red Scare and were subsequently deported to the newly formed Soviet Union. Although Goldman writes that she "longed" to return to her "native land" and aid in its reconstruction after the 1917 Revolutions, she "denied the right of the government" to force her.[20] While Goldman was optimistic of the revolutionary workers state, upon arrival her optimism was shaken by the Bolshevik dictatorship and their means of violent repression and coercion. As stated in Living My Life: "[The dictatorship’s] role was somewhat different from the one proclaimed in public. It was forcible tax collection at the point of guns, with its devastating effect on villages and towns. It was the elimination … of everyone who dared think aloud, and the spiritual death of the most militant elements whose intelligence, faith, and courage had really enabled the Bolsheviki to achieve their power."[21]

These feelings were compounded by the brutal repression of the Kronstadt sailors, who had rebelled under the pretense of anarchist principles.[22]

Goldman concludes her memoir by describing her flight from Soviet Russia and her subsequent travels abroad. Securing a visa to leave the Soviet Union, Goldman and Berkman arrived in Latvia on December 1, 1921. The couple traveled between Germany, France, England, Sweden, and Canada on temporary visas. However, after being commissioned by the New York World, Goldman published a series of articles describing her experiences in Russia—these articles would later be compiled into My Disillusionment in Russia.[23]

Critical reception

editLiving My Life received a positive review from the New York Times, and generally a positive reception from members of radical circles.

R.L. Duffus in the New York Times praised Goldman for the human portrayal of her "tempestuous" life. The most impressive aspect of Goldman's book, wrote Duffus, was the realization that what motivated Goldman was not "hatred" for the ruling classes, but "sympathy" for the masses. Extending this analysis to many of the other historical actors in Living My Life, Duffus concluded that perhaps the anarchists "hated authority because authority as they had known it had been neither kind nor just to them." Describing Goldman as a "vanishing" species motivated to radicalism out of pure humanity, Duffus described Living My Life as "one of the great books of its kind."[24]

In an anonymous "Letter to the Editor" published in The Washington Post, a writer compared Goldman's criticism of the Soviet Union to John Dewey's philosophy that "violence begets violence". They agreed with her insistence that progress could not be achieved through dictatorship.[25]

Some anarchists tried to settle personal issues. Helene Minkin, her former roommate and an anarchist in her own right, quickly published her memoirs in a serialized format in the Jewish daily newspaper Forverts (The Forward) in 1932. She wanted to defend her husband Johann Most, whom she had married in the 1890s, from Goldman's scathing criticism. Minkin rejected Goldman's statement that Most broke with Goldman and married Minkin because he wanted a wife who would take a domestic role. Minkin said she did not know the reason for the break between the two former friends (Most was originally a mentor to Goldman), but she said that her personal relationship with Most was neither subordinate nor traditional. Minkin described her role this way:

"Most, as I have noted once already, had the right to desire a little happiness for himself in the midst of his bitter and turbulent struggle… It would often bother me when I saw that Most wobbled a bit on his pedestal, and I supported him so that he wouldn’t be pushed down from his heights."[26]

Significance

editLiving My Life provides critical insight as to the mentality of radical immigrants in the United States during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. Goldman personally explores the often neglected topics of political violence and the nature of human sexuality in the early anarchist movement. At the beginning of Goldman's autobiography, the Haymarket bombing was a recent memory and American anarchists had already been tied to notions of violence and assassination. As historian John Higham posits, after Haymarket, the immigrant was widely stereotyped by American nativists as "a lawless creature given over to violence and disorder."[27] Goldman's early narrative emphasizes the violent tendencies of the movement, as it was only a few years following her arrival in New York City that she and Berkman attempted to assassinate Henry Frick. However, in the years following the attempt on Frick's life, Goldman and her allies turned away from the use of violence and assassination for political purposes. In the wake of McKinley's assassination, Goldman published an article that withheld direct praise for Leon Czolgosz and instead offered sympathy for those driven "by great social stress" to commit atrocities.[28]

Goldman's radicalism also influenced her personal views on sexuality. Coming from a traditional Russian Jewish family that stressed marriage and motherhood, Goldman rejected societal norms in favor of "free love."[29] As Goldman recalls in responding to critics of her open sexuality, "I insisted that our Cause could not expect me to become a nun… If it meant that, I did not want it… Even in spite of the condemnation of my own closest comrades I would live my beautiful idea."[30]

References

edit- ^ Wexler, Alice Ruth (February 2000). "Goldman, Emma". American National Biography Online.

- ^ "Emma Goldman, Anarchist Dead". New York Times. May 14, 1940.

- ^ Goldman, Emma (1970). Living My Life. New York: Dover Publications. pp. 16–17. ISBN 9780486225432.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. pp. 16–17.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. pp. 18–23.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. pp. 46–47.

- ^ Goldman, Living My Life, 36.

- ^ Goldman, Living My Life, 72–73, 77.

- ^ Goldman, Living My Life, 87.

- ^ Goldman, Living My Life, 92.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. p. 105.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. pp. 130–132.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. pp. 307–310.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. p. 303.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. p. 311.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. p. 318.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. p. 556.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. pp. 569–571.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. pp. 610, 650–651.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. p. 703.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. p. 754.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. p. 884.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. p. 953.

- ^ Duffus, R.L. (October 25, 1931). "An Anarchist Explains Herself: Emma Goldman Tells the Story of her Tempestuous Life". New York Times.

- ^ Aristotle (December 19, 1937). "Letter to the Editor". The Washington Post.

- ^ Minkin, Helene (2015). Goyens, Tom (ed.). A Storm in My Heart. Translated by Alisa Braun. Oakland: AK Press. pp. 52–53.

- ^ Higham, John (2011). Strangers in the Land. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. p. 55.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. p. 312.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. pp. 20–21.

- ^ Goldman. Living My Life. p. 56.

External links

edit- Living My Life entry at the Anarchy Archives

- Living My Life at RevoltLib