Livistona mariae, also known as the central Australian or red cabbage palm, is a species of flowering plant in the family Arecaceae.

| Livistona mariae | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Tracheophytes |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Monocots |

| Clade: | Commelinids |

| Order: | Arecales |

| Family: | Arecaceae |

| Tribe: | Trachycarpeae |

| Genus: | Livistona |

| Species: | L. mariae

|

| Binomial name | |

| Livistona mariae | |

It is found only in Australia with the best-known occurrence found in Palm Valley in Finke Gorge National Park, Northern Territory. There are more than 3,000 cabbage palms in Palm Valley, many of which are several hundred years old and form a lush oasis among the rugged rocks and gorges. This region is called Central Ranges xeric scrubland.

The palms are not relics from a previous age when Central Australia was much wetter, as previously thought.

New genetic analyses find that Livistona mariae arrived only 15,000 years ago. The red cabbage palm's closest relative, the Mataranka palm L. rigida, grows in two areas 800 to 1000 kilometres to the north on either side of the Gulf of Carpentaria—too far away, it would seem, for these species to be anything but distant relations. However, a 2010 study led by Australian biologists, including Bowman, and colleagues at Kyoto University in Japan found that L. mariae was genetically identical to L. rigida.[4][5]

Aboriginal legend recorded in 1894 by Carl Strehlow describes "gods from the north" bringing the seeds to Palm Valley, which accords with the more modern research.[6]

Common names

editVernacular names which have been applied to this species include: cabbage palm, central Australian cabbage palm, and red cabbage palm.[7][2]

Taxonomy

editA species of Livistona, palm trees of the family Arecaceae found in the horn of Africa, eastern Asia and Australia. L. mariae was found by Ernest Giles on his first expedition to the arid interior of Australia. The species description was published by Ferdinand von Mueller in his Fragmenta phytographiae Australiae.[8] Mueller referred to the taxon in an earlier work describing the Giles expedition,[a] although at this time the name was published without a formal description.[2]

Mueller did not designate a holotype, but a lectotype was selected by Tony Rodd in his 1998 revision of the Australian members of the genus Livistona, from among the two specimen sheets at the Melbourne herbarium attributed to Giles. Based on morphology, Rodd provisionally considered the closely related taxa L. mariae and L. rigida to be conspecific, and thus subsumed L. rigida as a subspecies of L. mariae. Rodd also described a new third taxon from specimens collected by him in Western Australia, the subspecies occidentalis. He furthermore noted the partial misapplication of the name to L. alfredii by Mueller in the same work.[9][10]

Rodd's 1998 circumscription of the species is summarised as:[2]

- Livistona mariae F.Muell.

- Livistona mariae subsp. mariae – synonymous with Mueller's description of the population at the 'Palm Grove Oasis'.

- Livistona mariae subsp. rigida (Becc.) Rodd – previously described as a species by Odoardo Beccari.

- Livistona mariae subsp. occidentalis Rodd

In 2004 the authors preparing a treatment of Australian populations of the family Arecaceae for the Flora of Australia, published a note that they would now follow Rodd's interpretation.[10] In his 2009 monograph on the entire genus Livistona, however, John Leslie Dowe, one of the authors mentioned, once again recognised L. rigida as an independent species, rejecting Rodd's interpretation for the time being because he had stated it was provisional, and because he noted a number of morphological differences.[11]

Research that concluded a human agency introduced the plants to the area has resulted in changes to the population's taxonomic treatment and, consequently, required reappraisal of their conservation status as a species naturalised around 15,000 years ago rather than an endemic persisting since the Miocene era.[12]

Description

editA palm tree with shallow roots and large hairless fronds that are slightly waxy at the underside.[13] The height of the plant may be over twenty metres, with leaves over four metres on long petioles of a similar length. The base of the tree becomes wider and raised at an advanced age, the trunk gently tapers to a narrower width toward the crown.[14]

A description of the larger groves of this tree, which had been bypassed by the Giles expedition, was provided by a minister at Hermannsburg community.

Distribution

editThe distribution range of the nominate form is restricted to a locality known as the Palm Valley, an area where the Finke River passes through the MacDonnell Ranges.

The isolated occurrence of this palm found over one thousand kilometres away from its nearest known relative at the time – the subspecies rigida – had been supposed to be a relict population. The isolation of the population was supposed to have resulted from the increased aridity of the continent since the Miocene period, around fifteen million years before the present day, or conveyed by a river or other means of dispersal. An analysis of molecular evidence found a separation from L. rigida was strongly indicated to have occurred around fifteen thousand years ago. Exclusion of other potential means for the introduction of the palm to the region, such as fruit bats or other mechanisms of distribution, left the most parsimonious explanation that it had been subject to dispersal by humans. This accords with the myths of local peoples, which allude to its deliberate introduction, the use as a resource and food, and its maintenance.[13]

Ecology

editIn the Palm Valley a subsurface aquifer has provided constant moisture to the groves, in an area surrounded by extremes of climate, and the trees occupy niches within the landscape that insulate them from periodic flooding.[13]

Cultivation

editThe species is represented in cultivation by two of the subspecies, one from the central desert, the other from the tropical coast. Livistona mariae are slow growing palm trees that eventually attain a large height and an emblematic form.

The subspecies L. mariae subsp. mariae is a desirable garden specimen referred to as the central Australian cabbage palm and presented as a feature plant. A specimen in an exhibition – along with the cycad Macrozamia macdonnellii from the MacDonnell Ranges – sought to demonstrate the horticultural potential of central Australia flora in modern gardens at the Geelong Botanic Gardens.[15] A potentially tall tree with attractive foliage and fruit, Livistona mariae subsp. mariae has a may attain a height of 15 metres in cultivation. The surface pattern of the trunk is regular and neat in appearance, a feature of the persistent leaf bases of the earlier growth, and the width gradually narrows toward the crown. The leaves are reddish during early growth, forming fronds up to 3 m in length and extended out on a long petiole. The tree generally known as L. rigida, also misnamed as L. mariae subsp. mariae in horticulture, is similar in form to the central desert subspecies but potentially larger in size. The more robust trunk of this taxon may reach a height of 20 m and the leaves, also reddish when young, reach lengths up to 4 metres.[14]

This palm is best grown in Australia in the arid central regions, when provided with adequate moisture, and the wet tropical coastal to sub-coastal regions of the north-east of the continent, with the most success in gardens north of Coffs Harbour.[14]

Propagation of the plant is from seed.[14]

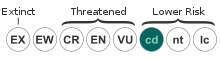

Conservation status

editThe three subspecies are listed in various regional and national conservation plans, the status and trajectory of these populations is classified separately. This recognises an arrangement by Rodd that placed Livistona rigida and L. mariae and his newly recognised taxon in a subspecific arrangement. The remote population at Finke Gorge, once listed as L. mariae, is thus amended to L. mariae subsp. mariae for conservation purposes following its taxonomic revision.[9]

The significance of these palms was recognised in a national conservation plan intended to improve the trajectory of thirty Australian plants, actions that would reduce factors that threaten the trees with extinction.[16] The classification by national EPBC legislation is vulnerable, with identified threats including an increased risk of fire as a result of invasive grasses, couch and buffel grass, alterations to availability of ground water and the impact of increased tourism.[17] A large number of the trees are protected by occurring within the Finke Gorge National Park, some fringing groves of the palm are found on pastoral land and tourist areas and are subject to separate conservation actions.

References

edit- ^ Johnson, D. (1998). "Livistona mariae". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 1998: e.T38597A10131164. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.1998.RLTS.T38597A10131164.en. Retrieved 17 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d "Livistona mariae". Australian Plant Name Index, IBIS database. Centre for Plant Biodiversity Research, Australian Government.

- ^ Mueller, F.J.H. von (1878) Fragmenta Phytographiae Australiae 11(89): 54.

- ^ Zielinski, S. (2012) Ancient Palm Not So Ancient After All Retrieved March 11, 2012.

- ^ Crisp, M.D.; Isagi, Y.; Kato, Y.; Cook, L.G.; Bowman, D.M.J.S. (2010). "Livistona palms in Australia: Ancient relics or opportunistic immigrants?". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 54 (2): 512–523. Bibcode:2010MolPE..54..512C. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2009.09.020. ISSN 1055-7903. PMID 19766198.

- ^ "Research findings back up Aboriginal legend on origin of Central Australian palm trees". ABC News. 3 April 2015. Retrieved 5 April 2015.

- ^ Department of the Environment. "Livistona mariae subsp. mariae — Central Australian Cabbage Palm, Red Cabbage Palm". Species Profile and Threats Database. Commonwealth of Australia.

- ^ Erickson, R. (1978). Ernest Giles: explorer and traveller, 1835–1897. Hesperian Press. ISBN 0859052400.

- ^ a b Rodd, A. (21 December 1998). "Revision of Livistona (Arecaceae) in Australia". Telopea. 8 (1): 49–153. doi:10.7751/telopea19982015.

- ^ a b Dowe, John Leslie; Jones, D.L. (2004). "Nomenclatural changes for two Australian species of Livistona R. Br. (Arecaceae)". Austrobaileya. 6 (4): 979–981. doi:10.5962/p.299710. ISSN 0155-4131. JSTOR 41739077.

- ^ Dowe, John Leslie (2009). "A taxonomic account of Livistona R.Br. (Arecaceae)" (PDF). Gardens' Bulletin Singapore. 60: 185–344. Retrieved 11 October 2020.

- ^ Trudgen, M.S.; Webber, B.L.; Scott, J.K. (22 August 2012). "Human-mediated introduction of Livistona palms into central Australia: conservation and management implications". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1745): 4115–4117. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.1545. PMC 3441089. PMID 22915667.

- ^ a b c Kondo, T.; Crisp, M.D.; Linde, C.; Bowman, D.M.J.S.; Kawamura, K.; Kaneko, S.; Isagi, Y. (7 March 2012). "Not an ancient relic: the endemic Livistona palms of arid central Australia could have been introduced by humans". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 279 (1738): 2652–2661. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0103. PMC 3350701. PMID 22398168.

- ^ a b c d Wrigley, J.W.; Fagg, M.A. (2003). Australian native plants : cultivation, use in landscaping and propagation (5th ed.). Sydney: Reed New Holland. pp. 565–566. ISBN 1876334908.

- ^ Arnott, J. (2003). "Geelong's Botanic Gardens". Australian Garden History: Journal of the Australian Garden History Society. 14 (4). Australian Garden History Society: 10.

- ^ Department of the Environment and Energy. "30 plants by 2020". Department of the Environment and Energy. Australian Government. Retrieved 5 April 2019.

- ^ Department of the Environment and Energy. "Central Australian cabbage palm". Threatened species intro.

Notes

edit- ^ Giles, E. Geographic Travels in Central Australia p. 222 (1875)