In statistics and business, a long tail of some distributions of numbers is the portion of the distribution having many occurrences far from the "head" or central part of the distribution. The distribution could involve popularities, random numbers of occurrences of events with various probabilities, etc.[1] The term is often used loosely, with no definition or an arbitrary definition, but precise definitions are possible.

In statistics, the term long-tailed distribution has a narrow technical meaning, and is a subtype of heavy-tailed distribution.[2][3][4] Intuitively, a distribution is (right) long-tailed if, for any fixed amount, when a quantity exceeds a high level, it almost certainly exceeds it by at least that amount: large quantities are probably even larger.[a] Note that there is no sense of the "long tail" of a distribution, but only the property of a distribution being long-tailed.

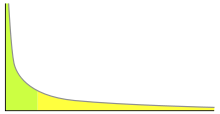

In business, the term long tail is applied to rank-size distributions or rank-frequency distributions (primarily of popularity), which often form power laws and are thus long-tailed distributions in the statistical sense. This is used to describe the retailing strategy of selling many unique items with relatively small quantities sold of each (the "long tail")—usually in addition to selling fewer popular items in large quantities (the "head"). Sometimes an intermediate category is also included, variously called the body, belly, torso, or middle. The specific cutoff of what part of a distribution is the "long tail" is often arbitrary, but in some cases may be specified objectively; see segmentation of rank-size distributions.

The long tail concept has found some ground for application, research, and experimentation. It is a term used in online business, mass media, micro-finance (Grameen Bank, for example), user-driven innovation (Eric von Hippel), knowledge management, and social network mechanisms (e.g. crowdsourcing, crowdcasting, peer-to-peer), economic models, marketing (viral marketing), and IT Security threat hunting within a SOC (Information security operations center).

History

editFrequency distributions with long tails have been studied by statisticians since at least 1946.[5] The term has also been used in the finance[6] and insurance business[7] for many years. The work of Benoît Mandelbrot in the 1950s and later has led to him being referred to as "the father of long tails".[8]

The long tail was popularized by Chris Anderson in an October 2004 Wired magazine article, in which he mentioned Amazon.com, Apple and Yahoo! as examples of businesses applying this strategy.[7][9] Anderson elaborated the concept in his book The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More.

Anderson cites research published in 2003 by Erik Brynjolfsson, Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, and Michael D. Smith, who first used a log-linear curve on an XY graph to describe the relationship between Amazon.com sales and sales ranking. They showed that the primary value of the internet to consumers comes from releasing new sources of value by providing access to products in the long tail.[10]

Business

editThe distribution and inventory costs of businesses successfully applying a long tail strategy allow them to realize significant profit out of selling small volumes of hard-to-find items to many customers instead of only selling large volumes of a reduced number of popular items. The total sales of this large number of "non-hit items" is called "the long tail".

Given enough choice, a large population of customers, and negligible stocking and distribution costs, the selection and buying pattern of the population results in the demand across products having a power law distribution or Pareto distribution. It is important to understand why some distributions are normal vs. long tail (power) distributions. Chris Anderson argues that while quantities such as human height or IQ follow a normal distribution, in scale-free networks with preferential attachments, power law distributions are created, i.e. because some nodes are more connected than others (like Malcolm Gladwell's “mavens” in The Tipping Point).[11][12]

Statistical meaning

editThe long tail is the name for a long-known feature of some statistical distributions (such as Zipf, power laws, Pareto distributions and general Lévy distributions). In "long-tailed" distributions a high-frequency or high-amplitude population is followed by a low-frequency or low-amplitude population which gradually "tails off" asymptotically. The events at the far end of the tail have a very low probability of occurrence.

As a rule of thumb, for such population distributions the majority of occurrences (more than half, and where the Pareto principle applies, 80%) are accounted for by the first 20% of items in the distribution.

Power law distributions or functions characterize an important number of behaviors from nature and human endeavor. This fact has given rise to a keen scientific and social interest in such distributions, and the relationships that create them. The observation of such a distribution often points to specific kinds of mechanisms, and can often indicate a deep connection with other, seemingly unrelated systems. Examples of behaviors that exhibit long-tailed distribution are the occurrence of certain words in a given language, the income distribution of a business or the intensity of earthquakes (see: Gutenberg–Richter law).

Chris Anderson's and Clay Shirky's articles highlight special cases in which we are able to modify the underlying relationships and evaluate the impact on the frequency of events. In those cases the infrequent, low-amplitude (or low-revenue) events – the long tail, represented here by the portion of the curve to the right of the 20th percentile – can become the largest area under the line. This suggests that a variation of one mechanism (internet access) or relationship (the cost of storage) can significantly shift the frequency of occurrence of certain events in the distribution. The shift has a crucial effect in probability and in the customer demographics of businesses like mass media and online sellers.

However, the long tails characterizing distributions such as the Gutenberg–Richter law or the words-occurrence Zipf's law, and those highlighted by Anderson and Shirky are of very different, if not opposite, nature: Anderson and Shirky refer to frequency-rank relations, whereas the Gutenberg–Richter law and the Zipf's law are probability distributions. Therefore, in these latter cases "tails" correspond to large-intensity events such as large earthquakes and most popular words, which dominate the distributions. By contrast, the long tails in the frequency-rank plots highlighted by Anderson and Shirky would rather correspond to short tails in the associated probability distributions, and therefore illustrate an opposite phenomenon compared to the Gutenberg–Richter and the Zipf's laws.

Chris Anderson and Clay Shirky

editUse of the phrase the long tail in business as "the notion of looking at the tail itself as a new market" of consumers was first coined by Chris Anderson.[13] The concept drew in part from a February 2003 essay by Clay Shirky, "Power Laws, Weblogs and Inequality",[14] which noted that a relative handful of weblogs have many links going into them but "the long tail" of millions of weblogs may have only a handful of links going into them. Anderson described the effects of the long tail on current and future business models beginning with a series of speeches in early 2004 and with the publication of a Wired magazine article in October 2004. Anderson later extended it into the book The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business is Selling Less of More (2006).

Anderson argues that products in low demand or that have a low sales volume can collectively make up a market share that rivals or exceeds the relatively few current bestsellers and blockbusters, if the store or distribution channel is large enough. Anderson cites earlier research by Erik Brynjolfsson, Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, and Michael D. Smith, that showed that a significant portion of Amazon.com's sales come from obscure books that are not available in brick-and-mortar stores. The long tail is a potential market and, as the examples illustrate, the distribution and sales channel opportunities created by the Internet often enable businesses to tap that market successfully.

In his Wired article Anderson opens with an anecdote about creating a niche market for books on Amazon. He writes about a book titled Touching the Void about a near-death mountain climbing accident that took place in the Peruvian Andes. Anderson states the book got good reviews, but didn't have much commercial success. However, ten years later a book titled Into Thin Air by Jon Krakauer was published and Touching the Void began to sell again. Anderson realized that this was due to Amazon's recommendations. This created a niche market for those who enjoy books about mountain climbing even though it is not considered a popular genre supporting the long tail theory.

An Amazon employee described the long tail as follows: "We sold more books today that didn't sell at all yesterday than we sold today of all the books that did sell yesterday."[15]

Anderson has explained the term as a reference to the tail of a demand curve.[16] The term has since been rederived from an XY graph that is created when charting popularity to inventory. In the graph shown above, Amazon's book sales would be represented along the vertical axis, while the book or movie ranks are along the horizontal axis. The total volume of low popularity items exceeds the volume of high popularity items.

Academic research

editEffects of online access

editErik Brynjolfsson, Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, and Michael D. Smith found that a large proportion of Amazon.com's book sales come from obscure books that were not available in brick-and-mortar stores. They then quantified the potential value of the long tail to consumers. In an article published in 2003, these authors showed that, while most of the discussion about the value of the Internet to consumers has revolved around lower prices, consumer benefit (a.k.a. consumer surplus) from access to increased product variety in online book stores is ten times larger than their benefit from access to lower prices online.[17]

The longer tail over time

editA subsequent study by Erik Brynjolfsson, Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, and Michael D. Smith[18] found that the long tail has grown longer over time, with niche books accounting for a larger share of total sales. Their analyses suggested that by 2008, niche books accounted for 36.7% of Amazon's sales while the consumer surplus generated by niche books has increased at least fivefold from 2000 to 2008. In addition, their new methodology finds that, while the widely used power laws are a good first approximation for the rank-sales relationship, the slope may not be constant for all book ranks, with the slope becoming progressively steeper for more obscure books.

In support of their findings, Wenqi Zhou and Wenjing Duan not only find a longer tail but also a fatter tail by an in-depth analysis on consumer software downloading pattern in their paper "Online user reviews, product variety, and the long tail".[19] The demand for all products decreases, but the decrease for the hits is more pronounced, indicating the demand shifting from the hits to the niches over time. In addition, they also observe a superstar effect in the presence of the long tail. A small number of very popular products still dominates the demand.

"Goodbye Pareto Principle"

editIn a 2006 working paper titled "Goodbye Pareto Principle, Hello Long Tail",[20] Erik Brynjolfsson, Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, and Duncan Simester found that, by greatly lowering search costs, information technology in general and Internet markets in particular could substantially increase the collective share of hard-to-find products, thereby creating a longer tail in the distribution of sales.

They used a theoretical model to show how a reduction in search costs will affect the concentration in product sales. By analyzing data collected from a multi-channel retailing company, they showed empirical evidence that the Internet channel exhibits a significantly less concentrated sales distribution, when compared with traditional channels. An 80/20 rule fits the distribution of product sales in the catalog channel quite well, but in the Internet channel, this rule needs to be modified to a 72/28 rule in order to fit the distribution of product sales in that channel. The difference in the sales distribution is highly significant, even after controlling for consumer differences.

Demand-side and supply-side drivers

editThe key supply-side factor that determines whether a sales distribution has a long tail is the cost of inventory storage and distribution. Where inventory storage and distribution costs are insignificant, it becomes economically viable to sell relatively unpopular products; however, when storage and distribution costs are high, only the most popular products can be sold. For example, a traditional movie rental store has limited shelf space, which it pays for in the form of building overhead; to maximize its profits, it must stock only the most popular movies to ensure that no shelf space is wasted. Because online video rental provider (such as Amazon.com or Netflix) stocks movies in centralized warehouses, its storage costs are far lower and its distribution costs are the same for a popular or unpopular movie. It is therefore able to build a viable business stocking a far wider range of movies than a traditional movie rental store. Those economics of storage and distribution then enable the advantageous use of the long tail: for example, Netflix finds that in aggregate, "unpopular" movies are rented more than popular movies.

An MIT Sloan Management Review article titled "From Niches to Riches: Anatomy of the Long Tail"[21] examined the long tail from both the supply side and the demand side and identifies several key drivers. On the supply side, the authors point out how e-tailers' expanded, centralized warehousing allows for more offerings, thus making it possible for them to cater to more varied tastes.[22]

On the demand side, tools such as search engines, recommendation software, and sampling tools are allowing customers to find products outside their geographic area. The authors also look toward the future to discuss second-order, amplified effects of Long Tail, including the growth of markets serving smaller niches.

Not all recommender systems are equal, however, when it comes to expanding the long tail. Some recommenders (i.e. certain collaborative filters) can exhibit a bias toward popular products, creating positive feedback, and actually reduce the long tail. A Wharton study details this phenomenon along with several ideas that may promote the long tail and greater diversity.[23]

A 2010 study conducted by Wenqi Zhou and Wenjing Duan[19] further points out that the demand side factor (online user reviews) and the supply side factor (product variety) interplay to influence the long tail formation of user choices. Consumers' reliance on online user reviews to choose products is significantly influenced by the quantity of products available. Specifically, they find that the impacts of both positive and negative user reviews are weakened as product variety goes up. In addition, the increase in product variety reduces the impact of user reviews on popular products more than it does on niche products.

Networks, crowds, and the long tail

editThe "crowds" of customers, users and small companies that inhabit the long-tail distribution can perform collaborative and assignment work. Some relevant forms of these new production models are:

- The peer-to-peer collaboration groups that produce open-source software or create wikis such as Wikipedia.

- The crowdsourcing model, in which a company outsources work to a large group of market players using a collaborative online platform.

- The model of crowdcasting, is the process of building a network of users and then delivering challenges or tasks to be solved with the purpose of gaining insights or innovative ideas.

- Work performed by individuals in commons-like, non-market networks, described in the work of Yochai Benkler.[24]

The demand-side factors that lead to the long tail can be amplified by the "networks of products" which are created by hyperlinked recommendations across products. An MIS Quarterly article by Gal Oestreicher-Singer and Arun Sundararajan shows that categories of books on Amazon.com which are more central and thus influenced more by their recommendation network have significantly more pronounced long-tail distributions. Their data across 200 subject areas shows that a doubling of this influence leads to a 50% increase in revenues from the least popular one-fifth of books.[25]

Turnover within the long tail

editThe long-tail distribution applies at a given point in time, but over time the relative popularity of the sales of the individual products will change.[26] Although the distribution of sales may appear to be similar over time, the positions of the individual items within it will vary. For example, new items constantly enter most fashion markets. A recent fashion-based model [27] of consumer choice, which is capable of generating power law distributions of sales similar to those observed in practice,[28] takes into account turnover in the relative sales of a given set of items, as well as innovation, in the sense that entirely new items become offered for sale.

There may be an optimal inventory size, given the balance between sales and the cost of keeping up with the turnover. An analysis based on this pure fashion model[29] indicates that, even for digital retailers, the optimal inventory may in many cases be less than the millions of items that they can potentially offer. In other words, by proceeding further and further into the long tail, sales may become so small that the marginal cost of tracking them in rank order, even at a digital scale, might be optimised well before a million titles, and certainly before infinite titles. This model can provide further predictions into markets with long-tail distribution, such as the basis for a model for optimizing the number of each individual item ordered, given its current sales rank and the total number of different titles stocked.

Long-tailed distributions in diplomacy

editFrom a given country's viewpoint, diplomatic interactions with other countries likewise exhibit a long tail.[30] Strategic partners receive the largest amount of diplomatic attention, while a long tail of remote states obtains just an occasional signal of peace. The fact that even allegedly "irrelevant" countries obtain at least rare amicable interactions by virtually all other states was argued to create a societal surplus of peace, a reservoir that can be mobilized in case a state needs it. The long tail thus functionally resembles "weak ties" in interpersonal networks.

Business models

editCompetitive impact

editBefore a long tail works, only the most popular products are generally offered. When the cost of inventory storage and distribution fall, a wide range of products become available. This can, in turn, have the effect of reducing demand for the most popular products. For example, a small website that focuses on niches of content can be threatened by a larger website which has a variety of information (such as Yahoo) Web content. The big website covers more variety while the small website has only a few niches to choose from.

The competitive threat from these niche sites is reduced by the cost of establishing and maintaining them and the effort required for readers to track multiple small web sites. These factors have been transformed by easy and cheap web site software and the spread of RSS. Similarly, mass-market distributors like Blockbuster may be threatened by distributors like LoveFilm, which supply the titles that Blockbuster doesn't offer because they are not already very popular.

Internet companies

editSome of the most successful Internet businesses have used the long tail as part of their business strategy. Examples include eBay (auctions), Yahoo! and Google (web search), Amazon (retail), and iTunes Store (music and podcasts), amongst the major companies, along with smaller Internet companies like Audible (audio books) and LoveFilm (video rental). These purely digital retailers also have almost no marginal cost, which is benefiting the online services, unlike physical retailers that have fixed limits on their products. The internet can still sell physical goods, but at an unlimited selection and with reviews and recommendations.[31] The internet has opened up larger territories to sell and provide its products without being confined to just the "local Markets" such as physical retailers like Target or even Walmart. With the digital and hybrid retailers there is no longer a perimeter on market demands.[32]

Video and multiplayer online games

editThe adoption of video games and massively multiplayer online games such as Second Life as tools for education and training is starting to show a long-tailed pattern. It costs significantly less to modify a game than it has been to create unique training applications, such as those for training in business, commercial flight, and military missions. This has led some[who?] to envision a time in which game-based training devices or simulations will be available for thousands of different job descriptions. [citation needed]

Microfinance and microcredit

editThe banking business has used internet technology to reach an increasing number of customers. The most important shift in business model due to the long tail has come from the various forms of microfinance developed.[citation needed]

As opposed to e-tailers, micro-finance is a distinctly low technology business. Its aim is to offer very small credits to lower-middle to lower class and poor people, that would otherwise be ignored by the traditional banking business. The banks that have followed this strategy of selling services to the low-frequency long tail of the sector have found out that it can be an important niche, long ignored by consumer banks.[33] The recipients of small credits tend to be very good payers of loans, despite their non-existent credit history. They are also willing to pay higher interest rates than the standard bank or credit card customer. It also is a business model that fills an important developmental role in an economy.[34]

Grameen Bank in Bangladesh has successfully followed this business model. In Mexico the banks Compartamos and Banco Azteca also service this customer demographic, with an emphasis on consumer credit. Kiva.org is an organization that provides micro credits to people worldwide, by using intermediaries called small microfinance organizations (S.M.O.'s)to distribute crowd sourced donations made by Kiva.org lenders.

User-driven innovation

editAccording to the user-driven innovation model, companies can rely on users of their products and services to do a significant part of the innovation work. Users want products that are customized to their needs. They are willing to tell the manufacturer what they really want and how it should work. Companies can make use of a series of tools, such as interactive and internet based technologies, to give their users a voice and to enable them to do innovation work that is useful to the company.

Given the diminishing cost of communication and information sharing (by analogy to the low cost of storage and distribution, in the case of e-tailers), long-tailed user driven innovation will gain importance for businesses.

In following a long-tailed innovation strategy, the company is using the model to tap into a large group of users that are in the low-intensity area of the distribution. It is their collaboration and aggregated work that results in an innovation effort. Social innovation communities formed by groups of users can perform rapidly the trial and error process of innovation, share information, test and diffuse the results.

Eric von Hippel of MIT's Sloan School of Management defined the user-led innovation model in his book Democratizing Innovation.[35] Among his conclusions is the insight that as innovation becomes more user-centered the information needs to flow freely, in a more democratic way, creating a "rich intellectual commons" and "attacking a major structure of the social division of labor".

In today's world, customers are eager to voice their opinions and shape the products and services they use. This presents a unique opportunity for companies to leverage interactive and internet-based technologies to give their users a voice and enable them to participate in the innovation process. By doing so, companies can gain valuable insights into their customer's needs and preferences, which can help drive product development and innovation. By creating a platform for their users to share their ideas and feedback, companies can harness the power of collaborative innovation and stay ahead of the competition. Ultimately, involving users in the innovation process is a win-win for both companies and their customers, as it leads to more tailored, effective products and services that better meet the needs of the end user.

Marketing

editThe drive to build a market and obtain revenue from the consumer demographic of the long tail has led businesses to implement a series of long-tail marketing techniques, most of them based on extensive use of internet technologies. Among the most representative are:

- New media marketing: The building and managing of social networks and online or virtual communities to extend the reach of marketing to the low-frequency, low-intensity consumer in a cost-effective way, often through blogs, RSS feeds and podcasts.[citation needed]

- Buzz marketing: The strategic use of word of mouth and transmission of commercial information from person to person in an online or real-world environment.

- Viral marketing: The intentional spreading of marketing messages using preexisting social networks, with an emphasis on the casual, non-intentional and low cost, commonly through YouTube videos, viral emails and standalone microsites.

- Pay per click and search engine optimization: The marketing of websites on search engines such as Google, Yahoo and Bing by focusing on long-tail keywords which have less competition.

- Demand-side platforms/DSPs: Similar to how search engine marketing monetizes the long tail of keywords, auction-oriented buying/selling mechanisms are also viable to help monetize the long tail of ad impressions available across niche publishers in the display advertising realm. Publishers utilize these ad exchange environments, such as Right Media or AdECN, to efficiently sell display inventory that might otherwise go unsold through direct sales force operations. As a result, by January 2011 between 20–25% of all US ad spending was derived from long tail advertisers.[36]

Cultural and political impact

editThis section possibly contains original research. (May 2015) |

The long tail has possible implications for culture and politics. Where the opportunity cost of inventory storage and distribution is high, only the most popular products are sold. But where the long tail works, minority tastes become available and individuals are presented with a wider array of choices. The long tail presents opportunities for various suppliers to introduce products in the niche category. These encourage the diversification of products. These niche products open opportunities for suppliers while concomitantly satisfying the demands of many individuals – therefore lengthening the tail portion of the long tail. In situations where popularity is currently determined by the lowest common denominator, a long-tail model may lead to improvement in a society's level of culture. The opportunities that arise because of the long tail greatly affect society's cultures because suppliers have unlimited capabilities due to infinite storage and demands that were unable to be met prior to the long tail are realized. At the end of the long tail, the conventional profit-making business model ceases to exist; instead, people tend to come up with products for varied reasons like expression rather than monetary benefit. In this way, the long tail opens up a large space for authentic works of creativity.

Cultural diversity

editTelevision is a good example of this: Chris Anderson defines long-tail TV in the context of "content that is not available through traditional distribution channels but could nevertheless find an audience."[37] Thus, the advent of services such as television on demand, pay-per-view and even premium cable subscription services such as HBO and Showtime open up the opportunity for niche content to reach the right audiences, in an otherwise mass medium. These may not always attract the highest level of viewership, but their business distribution models make that of less importance. As the opportunity cost goes down, the choice of TV programs grows and greater cultural diversity rises.

Distribution of independent content

editOften presented as a phenomenon of interest primarily to mass market retailers and web-based businesses, the long tail also has implications for the producers of content, especially those whose products could not – for economic reasons – find a place in pre-Internet information distribution channels controlled by book publishers, record companies, movie studios, and television networks. Looked at from the producers' side, the long tail has made possible a flowering of creativity across all fields of human endeavour.[citation needed] One example of this is YouTube, where thousands of diverse videos – whose content, production value or lack of popularity make them inappropriate for traditional television – are easily accessible to a wide range of viewers.

Contemporary literature

editThe intersection of viral marketing, online communities and new technologies that operate within the long tail of consumers and business is described in the novel by William Gibson, Pattern Recognition.

Military applications and security

editIn military thinking, John Robb applies the long tail to the developments in insurgency and terrorist movements, showing how technology and networking allows the long tail of disgruntled groups and criminals to take on the nation state and have a chance to win.

Criticisms

editA 2008 study by Anita Elberse, professor of business administration at Harvard Business School, calls the long tail theory into question, citing sales data which shows that the Web magnifies the importance of blockbuster hits.[38] On his blog, Chris Anderson responded to the study, praising Elberse and the academic rigor with which she explores the issue but drawing a distinction between their respective interpretations of where the "head" and "tail" begin. Elberse defined head and tail using percentages, while Anderson uses absolute numbers.[39] Similar results were published by Serguei Netessine and Tom F. Tan, who suggest that head and tail should be defined by percentages rather than absolute numbers.[40]

Also in 2008, a sales analysis of an unnamed UK digital music service by economist Will Page and high-tech entrepreneur Andrew Bud found that sales exhibited a log-normal distribution rather than a power law; they reported that 80% of the music tracks available sold no copies at all over a one-year period. Anderson responded by stating that the study's findings are difficult to assess without access to its data.[41][42]

See also

edit- Black swan theory

- Kolmogorov's zero–one law, also known as tail event.

- Mass customization

- Swarm intelligence

Explanatory notes

edit- ^ Formally, equivalently

References

editCitations

edit- ^ Alpheus Bingham and Dwayne Spradlin (2011). The Long Tail of Expertise. Pearson Education. p. 5. ISBN 9780132823135.

- ^ Asmussen, S. R. (2003). "Steady-State Properties of GI/G/1". Applied Probability and Queues. Stochastic Modelling and Applied Probability. Vol. 51. pp. 266–301. doi:10.1007/0-387-21525-5_10. ISBN 978-0-387-00211-8.

- ^ Levine, David M.; Stephan, David; Krehbiel, Timothy C.; Berenson, Mark L. Statistics for Managers using Microsoft Excel. 3rd edition. Prentice Hall, 2002, p. 124.

- ^ John Verzani (2004). Using R for Introductory Statistics. CRC Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-58488450-7.

- ^ A search for the phrase "long tail" in the database MathSciNet yielded 81 hits, the earliest being a 1946 paper by Brown and Tukey in the Annals of Mathematical Statistics (volume 17, pages 1–12).

- ^ Bessis, Jöel "Risk Management in Banking". Wiley, 1995

- ^ a b Quinion, Michael (24 December 2005). "Turns of Phrase: Long Tail". World Wide Words. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ Obrist, Hans Ulrich "The Father of Long Tails. An interview with Benoît Mandelbrot", Edge.org, 2008

- ^ Anderson, Chris. "The Long Tail" Wired, October 2004.

- ^ Brynjolfsson, Erik; Hu, Yu (Jeffrey); Smith, Michael D. (2003). "Consumer Surplus in the Digital Economy: Estimating the Value of Increased Product Variety at Online Booksellers". Management Science. 49 (11): 1580–1596. doi:10.1287/mnsc.49.11.1580.20580. hdl:1721.1/3516. ISSN 0025-1909.

- ^ Carr, Nicholas "The shape of the tail.", roughtype.com, 2006

- ^ Anderson, Chris (2006). scifoo: A problem with the Long Tail. New York, NY: Hyperion. ISBN 978-1-4013-0237-5.

- ^ See The origins of "The Long Tail"

- ^ "Power Laws, Weblogs and Inequality" Archived 2004-07-07 at the Wayback Machine, by Clay Shirky. February 8, 2003.

- ^ The Long Tail: Definitions: Final Round!, comment #3 by Josh Petersen.

- ^ "The Long Tail". NPR. 5 November 2004. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ Brynjolfsson, Erik; Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, and Michael D. Smith, "Consumer Surplus in the Digital Economy: Estimating the Value of Increased Product Variety at Online Booksellers", Management Science, 49 (11), November 2003. working paper version, April 2003

- ^ Bynjolfsson, Erik; Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, and Michael D. Smith, 2010, "The Longer Tail: The Changing Shape of Amazon's Sales Distribution Curve"

- ^ a b Zhou, Wenqi; Duan, Wenjing (21 November 2010). "Online User Reviews, Product Variety, and the Long Tail: An Empirical Investigation on Online Software Downloads". Electronic Commerce Research and Applications. 11 (3): 275–289. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2011.12.002. S2CID 23070895.

- ^ Brynjolfsson, Erik; Yu (Jeffrey) Hu, and Duncan Simester, 2006, "Goodbye Pareto Principle, Hello Long Tail: The Effect of Search Costs on the Concentration of Product Sales"

- ^ Brynjolfsson, Erik; Hu, Yu "Jeffrey"; Smith, Michael D. (Summer 2006). "From Niches to Riches: Anatomy of the Long Tail". MIT Sloan Management Review. 47 (4): 67–71. SSRN 918142.

- ^ Anderson, Chris (1 July 2006). "The Rise and Fall of the Hit". Wired. Vol. 14, no. 7.

- ^ Fleder, Daniel; Hosanagar, Kartik (May 2009). "Blockbuster Culture's Next Rise or Fall: The Impact of Recommender Systems on Sales Diversity". Management Science. 55 (5): 697–712. doi:10.1287/mnsc.1080.0974. SSRN 955984.

- ^ "Benkler, The Wealth of Networks". Benkler.org. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ Oestreicher-Singer, Gal and Arun Sundararajan (2012). "Recommendation Networks and the Long Tail of Electronic Commerce". MIS Quarterly. 36 (1): 65–83. doi:10.2307/41410406. JSTOR 41410406. SSRN 1324064.

- ^ Bentley, R. Alexander; Lipo, Carl P.; Herzog, Harold A.; Hahn, Matthew W. (2007). "Regular rates of popular culture change reflect random copying". Evolution and Human Behavior. 28 (3): 151–158. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.411.7668. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2006.10.002.

- ^ Highfield, Roger (16 June 2004). "Why are they so popular?". The Daily Telegraph. Archived from the original on 23 February 2006. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ Bentley, R.A.; Hahn, M.W.; Shennan, S.J. (2007). "Random drift and culture change". Proceedings of the Royal Society. 271 (1547): 1443–50. doi:10.1098/rspb.2004.2746. PMC 1691747. PMID 15306315.

- ^ Bentley, R. Alexander; Madsen, Mark E.; Ormerod, Paul (2009). "Physical space and long-tail markets". Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and Its Applications. 388 (5): 691–696. arXiv:0808.1655. Bibcode:2009PhyA..388..691B. doi:10.1016/j.physa.2008.11.009.

- ^ Nishikawa-Pacher, Andreas (2023). "Diplomatic complexity and long-tailed distributions: the function of non-strategic bilateral relations". International Politics. 60 (6): 1270–1293. doi:10.1057/s41311-023-00510-3.

- ^ Anderson, Chris (13 December 2004). "The Long Tail" (PDF). ChangeThis. Vol. 10, no. 1.

- ^ McDonald, Scott (September 2008). "The Long Tail and Its Implications for Media Audience Measurement". Journal of Advertising Research. 48 (3): 313–319. doi:10.2501/S0021849908080379. ISSN 0022-2437.

- ^ "Microcredit and Microfinance". The Global Development Research Center. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ "Vision and Mission Statement for Building Inclusive Financial Sectors". United Nations Capital Development Fund. Archived from the original on 31 December 2011. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ "Democratizing Innovation". MIT Press. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ "'Long Tail' Advertisers Are Back, U.S. Ad Expansion Reaches '03 Levels". MediaDailyNews. 2011-01-04. Retrieved 2014-01-20.

- ^ Chris Anderson. The Long Tail TV: Conclusion. The Long Tail Blog. January 17, 2005.

- ^ Elberse, Anita (July 2008). "Should You Invest in the Long Tail?". Harvard Business Review.

- ^ Anderson, Chris (27 June 2008). "Excellent HBR piece challenging the Long Tail". The Long Tail Blog.

- ^ "Rethinking the Long Tail Theory: How to Define 'Hits' and 'Niches'". Knowledge@Wharton. 16 September 2009.

- ^ Anderson, Chris (8 November 2008). "More Long Tail debate: mobile music no, search yes". The Long Tail. Retrieved 25 December 2011.

- ^ Foster, Patrick (22 December 2008). "Long Tail theory contradicted as study reveals 10m digital music tracks unsold". The Times. Times Online.

General and cited references

edit- Anderson, Chris (2006). The Long Tail: Why the Future of Business Is Selling Less of More. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 978-1-4013-0237-5.

- The Long Tail—a computer model by Fiona Maclachlan, The Wolfram Demonstrations Project

External links

edit- Media related to The Long Tail at Wikimedia Commons