Los Caprichos (The Caprices) is a set of 80 prints in aquatint and etching created by the Spanish artist Francisco Goya in 1797–1798 and published as an album in 1799. The prints were an artistic experiment: a medium for Goya's satirizing Spanish society at the end of the 18th century, particularly the nobility and the clergy. Goya in his plates humorously and mercilessly criticized society while aspiring to more just laws and a new educational system. Closely associated with the Enlightenment, the criticisms are far-ranging and acidic. The images expose the predominance of superstition, religious fanaticism, the Inquisition, religious orders, the ignorance and inabilities of the various members of the ruling class, pedagogical shortcomings, marital mistakes, and the decline of rationality.[1]

Goya added brief explanations of each image to a manuscript, now in the Museo del Prado, which help explain his often cryptic intentions, as do the titles printed below each image. Aware of the risk he was taking, to protect himself, he gave many of his prints imprecise labels, especially the satires of the aristocracy and the clergy. He also diluted the messaging by illogically arranging the engravings. Goya explained in an announcement that he chose subjects "from the multitude of faults and vices common in every civil society, as well as from the vulgar prejudices and lies authorized by custom, ignorance or self-interest, those that he has thought most suitable matter for ridicule".

Despite the relatively vague language of Goya's captions in the Caprichos, Goya’s contemporaries understood the engravings, even the most ambiguous ones, as a direct satire of their society, even alluding to specific individuals, though the artist always denied the associations.

The series was published in February 1799; however, just 14 days after going on sale, when Manuel Godoy and his affiliates lost power, the painter hastily withdrew the copies still available for fear of the Inquisition. In 1807, to save the Caprichos, Goya decided to offer the king the plates and the 240 unsold copies, destined for the Royal Calcography, in exchange for a lifetime pension of twelve thousand reales per year for his son Javier.[2]

The work was a tour-de-force critique of 18th-century Spain, and humanity in general, from the point of view of the Enlightenment. The informal style, as well as the depiction of contemporary society found in Caprichos, makes them (and Goya himself) a precursor to the modernist movement almost a century later. Capricho No. 43, The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters in particular has attained an iconic status.

Goya's series, and the last group of prints in his series The Disasters of War, which he called "caprichos enfáticos" ("emphatic caprices"), are far from the spirit of light-hearted fantasy the term "caprice" usually suggests in art.

Thirteen official editions are known: one from 1799, five in the 19th century, and seven in the 20th century, with the last one in 1970 being carried out by the Royal Academy of Fine Arts of San Fernando.

Los Caprichos have influenced generations of artists from movements as diverse as French Romanticism, Impressionism, German Expressionism or Surrealism. Ewan MacColl and André Malraux considered Goya one of the precursors of modern art, citing the innovations and ruptures of the Caprichos.

History

editIn 1799, a collection of eighty prints of whimsical subjects etched by the painter Francisco de Goya, who was 53 years old, was put up for sale. Through ridicule, extravagance, and fantasy, these engravings criticized the society of Spain at the time.

To understand the genesis of the Caprichos, it is necessary to consider the years preceding them. In the 1780s, Goya began to interact with some of the most important intellectuals in the country, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, Juan Meléndez Valdés, Leandro Fernández de Moratín and Juan Agustín Ceán Bermúdez, who introduced him to the ideals of the Enlightenment. He shared their opposition to religious fanaticism, superstition, the Inquisition and religious orders. They aspired to fairer laws and an educational system based on the individual.[3]

In 1788 Charles IV came to the throne. After the coronation of Charles IV, Goya portrayed the king with his wife, Queen María Luisa, subsequently being named Court Painter.[4]

The period of the French Revolution had repercussions in Spain. Charles IV suppressed Enlightenment ideas and removed the most advanced thinkers from public life. Goya's enlightened friends were persecuted, and the threat of the prison of Cabarrús, as well as the exile of Jovellanos must have worried Goya.[5]

On a trip from Madrid to Seville in January 1793, Goya fell ill, perhaps from an attack of apoplexy. To convalesce, he was taken to Cádiz to the home of his enlightened friend Sebastián Martínez, availing of the good doctors of the Faculty and the benevolent climate of the city. Though it is unclear what illness Goya had, several hypotheses have been suggested: venereal disease, thrombosis, Meniere's syndrome, Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada syndrome and, lately, lead poisoning. Goya became deaf; at first he couldn't see well; and he walked maintaining balance with difficulty. Illness kept him in Cádiz for almost half a year. After Goya returned to Madrid, he was unable to resume his normal activities for a long time. Thus, in March 1794, the director of the Fábrica de Tapices (Tapestry Factory) believed that Goya was unable to paint because of his illness. In April 1797, Goya resigned as Director of the Academy due to prolonged convalescence from his ailments.[6]

Serious illness caused a great crisis in Goya’s life. The shock of being one step away from death and permanent deafness engendered a crucial change in his life. His work after 1793 has a new depth and seriousness.[7] His attitude became more critical, and his deafness had sharpened his inner consciousness. His language became rich and enigmatic. The Enlightenment ideology became a constant reference.[8] This was recognized by Francisco Zapater, his friend and biographer, who stated that Goya in the last decade of the 18th century, "was agitated by the new ideas that were sweeping Europe."[9] However, his ideology evolved towards skepticism. He went from trusting in enlightened thought that sought to improve society by showing its faults and vices to becoming a precursor of the current world that lost confidence in the intellectual capacity of men to regenerate their society and only found a dark world without ideals. This transition and evolution in his thinking occurred during the creation of the Caprichos and can be clearly seen in plates depicting satire with clearly illustrated inspiration and others depicting his skepticism in the possibilities of man.[10]

Critics of Goya's art distinguish between his work before and after his illness, considering the latter the most valuable and authentic style of the painter. In a letter that he wrote to his friend from the Academy, Bernardo Iriarte, on January 4, 1794, Goya gives important testimony that while convalescing from his serious illness, his works depicted observations and revelations that would not have been possible in his commissioned works. He referred to innovative small paintings of themes related to the Inquisition or the asylum where he had developed a personal and intense vision with an extremely expressive style. Thus, Goya's illness establishes not only a chronological division of his art, it also establishes a division between commissioned works, subject to inevitable restrictions by the conventions of the time, and other more personal works for himself and friends where he expressed himself with total freedom.[11]

In 1796 Goya visited Andalusia and made a series of sketches, some of which anticipate Los Caprichos.

Drawing from Album A of the Duchess combing her hair. Chinese ink wash.

In 1796 Goya returned to Andalusia with Ceán Bermúdez, and after July he was in Sanlúcar de Barrameda with the Duchess of Alba, who had been widowed the previous month. The meeting with her represented a period of sensuality that was reflected in a series of masterful drawings where the duchess appears: Album A, or Album de Sanlúcar, that would inspire some of the themes of the Caprichos.[12] Also, the bitter ending and separation inspired other prints of the series.[13]

Later he made the drawings for the so-called Album B, or Sanlúcar-Madrid, where he criticized vices of his time through caricatures. In this album, he increased the effect of chiaroscuro, making use of light to emphasize visual areas of ideological importance. This expressionist and nonrealistic use of light, previously used in the paintings of the Charterhouse of Aula Dei (Cartuja de Aula Dei), Goya used profusely in the Caprichos. Also in this notebook, Goya began to write titles or phrases in the compositions. These stinging comments often have double meaning in the best Spanish literary tradition. Likewise, Goya began to fill his images with ambiguous visual meanings; the images and the texts enable several different interpretations of the drawings. The Caprichos innovated this characteristic in depth.[14]

In principle, Goya planned this Capricho to be the cover of his engravings. Here he portrayed himself in a very different way than he finally decided to present himself at the beginning of Los Caprichos: abstracted, half asleep, and surrounded by his obsessions. An owl hands him his drawing supplies, clearly indicating the origin of his inventions. He intended the cover title as: "Dreams, the First Universal Language. Drawn and engraved by Francisco de Goya. Year 1797. The Author Dreaming." His aim is to banish harmful vulgarities, and with this work of Caprichos promulgate the solid testimony of the truth."[16]

Goya initially conceived this series of prints as "Sueños" (Dreams) (and not as Caprichos), making at least 28 preparatory drawings, 11 of them from Album B (in the Prado Museum except for some that have disappeared). [16]

Los Sueños (Dreams) would be a graphic version of the literary dreams of the satirical writer Francisco de Quevedo, who wrote between 1607 and 1635 a series where he dreamed that he was conversing in Hell both with demons and the damned. In Quevedo's dreams, as later in the Caprichos, sinners retain their human form, or take on animal attributes that symbolize their vices, or are depicted as witches as in Dream No. 3. [17] The project for this edition consisted of 72 prints. A sales advertisement was published in 1797 specifying that the subscription period was going to last two months, since the plates had yet to be printed. The price set was 288 reales, payable in two months.[18]

Other precedents may have inspired Goya. For instance, the royal collections contained the works of Hieronymus Bosch, whose strange creatures were surely men and women whose vices had turned them into animals that represented their defects.[17] In Arriaga's satires (1784), men are seen converted into donkeys, monkeys or dogs; the ministers and thieves are wolves; and the clerks are cats (same as in Caprichos No. 21 and 24).[19]

At one point, Goya changed the name of his engravings to “Caprichos” and planned to use all but three of the Dreams as Caprichos. This has been determined because the drawings show signs of having been moistened for transfer to plates.[17] The word "Capricci" had been used in the well-known prints of Jacques Callot from 1617 and in the Capricci of Giambatista Tiepolo to refer to imaginations of reality.[20]

As an engraver Goya reached maturity in this series. He had previously made another series with engravings of paintings by Velázquez.[21] Goya had needed to learn to engrave because at that time painters did not know the engraving technique, which was considered a craftsman's work. The usual technique in Spain, engraving with a burin, required ten years to master. Goya learned a different technique, etching, which is similar to drawing. He also learned a second, more complicated technique, aquatint, which allowed him gradations of stains from white to black, similar to making washes in paint. Using both techniques simultaneously, which was something new, Goya obtained engravings that are very like paintings.[22] It is unknown where the coppers were stamped; Glendinning points out a printing press as possible, but according to Carderera, it was the painter's house or workshop.[23]

The definitive form of the Caprichos series of 80 prints was finished on January 17, 1799, as there is a receipt from the Osuna Archive that on that date they paid for 4 series purchased by the Duchess of Osuna. [24] [25]

In the Diario de Madrid of February 6, 1799, the sale of the collection was announced, along with the painter's motivation. A total of 300 copies was put up for sale.[26] The advertisement indicates that they were sold at the perfumery on the Calle del Desengaño No. 1 (ironically, Disillusion Street No. 1), the same building where Goya lived.[25]

According to the advertisement in Diario Madrid, Goya intended to imitate literature on censorship and human vices; an entire aesthetic, sociological, and moral program is reflected in the motives of his work.[27] Given the literary style of the advertisement, it is speculated that one of Goya's friends authored the text.[25] Another inference from the announcement is that the artist never intended to ridicule any specific individual. However, Goya’s contemporaries did see specific allusions, a very dangerous inference in that turbulent time. In general, the advertisement is reserved and cautious regarding possible accusations regarding its content.[28]

As has been noted, Goya associated with people committed to the fight for the reformation of Spanish life and embraced the Enlightenment program of renewal. The Diario Madrid coincided with the reflections of the enlightened about forces hostile to the development of reason.[29] Aware of the risk of criticism, and to protect himself, Goya gave his prints labels that were sometimes precise, but other times imprecise, especially for prints that criticized the aristocracy and the clergy.[13] Also, Goya softened the message by giving an illogical arrangement and numbering of the engravings. If he had followed a more logical sequence, his work would have undergone more stringent censorship and received explosive criticism, exposing him to greater consequences.[30]

Although Goya took risks, at the time of its publication, the Caprichos had the support of his enlightened friends who were once again in power since November 1797.[12] However, Godoy's fall from power and the absence of Jovellanos and Saavedra in the Government precipitated events. Perhaps wary of possible intervention by the Inquisition, Goya withdrew the Caprichos from sale.[31] Although in a later letter in 1803 to Miguel Cayetano Soler, Goya incorrectly stated that the series was on sale for two days; in actuality, they were on sale for fourteen days. It is assumed that Goya wanted to mitigate details that could harm him.[18]

The fear of the Inquisition, which then enforced public morality and sustained the existing society, was real, since these engravings attacked the clergy and the high nobility.[25]

The specific origins of the conflict between the Caprichos and the Inquisition is well documented in the book La Inquisición sin máscara (The Inquisition without a Mask), published in Cádiz in 1811 by the enlightened Antonio Puigblanch (under the pseudonym Nataniel Jomtob):

"In the famous collection of satirical prints known as Caprichos, by D. Francisco Goya y Lucientes, Court Painter of Charles IV, two are intended to mock the Inquisition. In the first, number 23, which presents an owl, the author rebukes the greed of the inquisitors in the following way. He paints a prisoner sitting on a stand or bench on top of a platform with a sambenito [A garment worn by the penitents of the Inquisition court. The sambenito was used to humiliate heretics and the condemned. The sambenito varied depending on the crime and the sentence. Penitents condemned to death wore a sambenito with flames, while penitents who repented wore a yellow sambenito.] and a coroza [An elongated paper cone placed on the head of certain condemned people as humiliation, painted with figures alluding to the crime or its punishment.], his head fallen on his chest with an embarrassed gesture, and the secretary reading the sentence from the pulpit in the presence of a large gathering of ecclesiastics, with this motto at the foot: 'Those powders.' The second part of the saying must be applied, which is: 'they brought this sludge.' The handwritten explanation states: the scops owls are the pastime and entertainment of a certain class of people. The motto must be applied not to the prisoner, as it seems at first sight, but to the court... This work, despite the veil in which its author covered it, whether depicting the objects in caricature or applying indirect or vague inscriptions to them, was directed at the Inquisition. Nevertheless, the sheets or plates were not lost because Mr. Goya hastened to offer them to the king, and the king ordered them to be deposited in the Chalcography Institute."[32]

The Inquisition understood that the caption referred, not to the prisoner as it seems at first glance, but to the court. For this reason, the work was denounced to the Inquisition.

Announcement for the sale of “Los Caprichos”

Diario «Madrid» Wednesday, February 6, 1799 "Collection of prints of whimsical matters, invented and etched by D. Francisco de Goya”

"The artist being convinced that condemnation of human faults and vices can also be the object of painting (although seemingly particular to eloquence and poetry), he has chosen as appropriate subjects for his work―among the multitude of extravagances and mistakes common in all civil society and among vulgar concerns and lies, inspired by custom, ignorance, or self-interest― those he believes most apt to provide material for ridicule while exciting the fantasy of the artist.

"Since most of the objects represented in this work are idealized, it may not be audacious to believe their defects perhaps will find justification among the intelligent. Considering that the artist has neither followed the examples of others nor copied directly from nature, and if imitation is as difficult as it is admirable when achieved; he should be admired who has exposed to the viewer's eyes forms and attitudes that completely deviate from what until now has only existed in the human mind, obscured and confused by lack of enlightenment or heated by the untethering of passions. It would be assuming too much in the fine arts to warn the public that in none of the compositions that make up this collection did the author intend to ridicule defects particular to one or another individual; which would really serve to narrow the limits of talent too much and to mistake the means by which the imitative arts produce perfect works. Painting (like poetry) chooses from the universal what it judges most appropriate for its purposes; it brings together, in a single fantastic portrayal, circumstances and characters that nature represents scattered among many, and ingeniously arranged; from this combination results that happy imitation by which a good craftsman acquires the title of innovator and not of servile copyist.”

"To be sold at Calle del Desengaño No. 1, a perfume and liquor store, payment of 320 reales for each collection of 80 prints."[33]

Los Caprichos were withdrawn from public sale very shortly after their release in 1799, after only 27 copies of the set had been purchased. In 1803, to save the Caprichos, Goya decided to offer the plates and all the available series (240) to the king, destined for the Royal Chalcography, in exchange for a pension for his son. In 1825 he would write that he had been denounced to the Inquisition.

Possibly Goya kept some of the series, which he sold in Cádiz during the War of Independence. According to the Prado Museum manuscript, the last page indicates that the bookseller Ranza took 37 copies. According to this, either Goya or the Royal Chalcography released copies for sale in Cádiz in 1811.[34] Considering that in the donation document to the king it was said that 27 copies were sold to the public,[35] this first series had a total of about 300 copies.

Therefore, it must have been the denunciation to the Inquisition that motivated the opportunistic transfer to the King’s Chalcography of this first edition, made in reddish or sepia ink.[18] It is significant that Goya held an ambivalent position, close to the enlightened, but strongly related to the traditional power as painter of the king and his aristocracy, which allowed him to request the king's help and obtain his protection.

As the work was enigmatic, aspiring to make sense of the plates, contemporary handwritten comments soon emerged that have been preserved. The manuscript conserved in the Prado Museum is the best known, as well as the most cautious and ambiguous. It avoids dangerous comments by giving a general and unspecific nature to the most compromising prints, especially those referring to religious and political matters. Two others, one that belonged to the playwright López de Ayala and the other in the National Library of Madrid, contain language that freely criticizes the clergy, politics, and even specific people.[36]

The second edition would have been made between 1821 and 1836, previously printed like all the following ones by the Royal National Chalcography. The last one is from 1936-1939 during the Spanish Civil War. Due to so many editions, the plates are deteriorated, and some can no longer reproduce the effects initially planned.[35] Tomás Harris considered that from print No. 1, the most used, a total of around two thousand prints must have been made.[37]

Goya devised more prints for the Caprichos that for unknown reasons he did not include in the series. Thus, three proofs of three different engravings are preserved in the National Library of Madrid and two proofs of two other engravings in the National Library of Paris. Furthermore, the Prado Museum has five drawings with signs of having been recorded on plates.[37]

Theme

editLos Caprichos lack an organized and coherent structure, but they have important thematic nuclei. The most prevalent themes are: the superstition around witches, which predominates after Capricho No. 43 and that serves to express ideas about evil in a tragicomic way; the life and behavior of friars; erotic satire relating to prostitution and the role of the matchmaker; and to a lesser extent social satire of unequal marriages, the education of children, and the Inquisition.[20]

Goya criticized these and other evils without following a rigorous order. In a radically new way, he showed a materialist and dispassionate vision, in contrast to the paternalistic social criticism carried out in the 18th century that directed its efforts to reform the erroneous behavior of man. Goya limited himself to showing apparently everyday dark scenes conceived in strange and unreal settings.[38]

In the first half he presented his most realistic and satirical engravings, criticizing the behavior of human beings from the perspective of reason. In the second part he shows fantastic engravings where he abandoned the rational point of view, and following the logic of the absurd, he painted delirious visions with strange beings.[39]

In the first part, one of the largest and most autobiographical groups is dedicated to erotic satire. The bitter disappointment in love with the Duchess of Alba is presented in several prints where he mainly criticizes women's inconstancy in love and impiety towards their lovers. Femininity is presented as a lure where the woman seduces without compromising her heart. Furthermore, and as a counterpoint, the confidante and guide of female lovers, the old matchmaker, appears in the background.[40]

Capricho No. 17: Bien tirada está (It is nicely stretched);

Capricho No. 27: ¿Quién más rendido? (Who surrendered more? (Details))

A second group criticizes social conventions, which Goya does by deforming to the point of exaggeration traits that embody human vices and blunders. Contemplation of these individuals leaves no room for doubt; the ferocity with which they are presented inevitably leads us to condemn them out of hand.[41] Marriages of convenience and male lasciviousness are criticized in the images presented below.[41]

Capricho No. 14: ¡Qué sacrificio! (What a sacrifice!);

Capricho No. 72: No te escaparás. (You will not escape.) (Details)

There are also several cases where two prints are related to each other, either because one is a chronological continuation of the other or because they present the same topic in a different way.

The images below show two related prints. At the same time, Capricho No. 42, "You who cannot" is also included in another group, that of the Asnerias (a Medieval Latin word meaning "donkey farm") (six plates from Caprichos Nos. 37 to 42), where imitating the fabulists, the stupidity of the donkey in criticizing the intellectual professions is represented.[42]

Capricho No. 63: ¡Miren que graves! (Look how solemn they are!)

In Capricho No. 42, two peasants carry the nobility and the idle friars on their backs like beasts of burden, represented as two happy donkeys. The peasants suffer from carrying the extreme burden. The title "You who cannot" is the first part of a popular saying that concludes "carry me on your back", and highlights what the enlightened people of the late 18th century were already beginning to think about the incapacity and impotence of the people. Goya also adds the usual metaphor of the people carrying the idle classes; however, he represents the leisure classes as donkeys while he represents the peasants with the dignity of men. The image shows us that the world is upside down and that the social system is totally inadequate.[43]

Capricho No. 63 deals with the same topic, but the failure of agrarian reform has provoked the author's pessimism and has led to his radicalization. Thus, the peasants have become beings like donkeys, while the horsemen now are represented as two monsters, the first with the head, hands, and feet of a bird of prey and the second with the face of a fool and the ears of a donkey, engaged in prayer. Earlier there might have been hope that men would get rid of the burden of the stupid donkeys, but in the second picture there is no hope, the oppressed have become brutalized and one of the monsters that dominates them is a voracious bird.[44]

The most original group, known as “Witchcraft” or “Dreams,” is where Goyesque fantasy reached its maximum expression with the most elaborate inventions. It is surprising to notice how radically the Goyesque inspiration changes here. José Ortega y Gasset said that in this Goya Romanticism suddenly springs up for the first time a world of mysterious and demonic beings that man carries in the recesses of his being. Azorín spoke of the demonic reality of the Caprichos compared to the realistic vision of the other masters. López Rey believed that in this part the evil in Los Caprichos is reduced to the absurd, drawing the demonic as the result of man's error in separating himself from the ways of reason.[45]

According to Edith Helman, who studied the literary references of the Caprichos, the most direct inspiration for the Witchcrafts was found by Goya in his friend Moratín and in the latter's reprint of the Auto de Fe on witchcraft that the Inquisition held in Logroño in 1610. Although Inquisition proceedings were rare at the end of the 18th century, the most important trials of the 17th century were available. Moratín, who saw in these trials a monstrous farce for the supposed witches, decided to republish the most famous of all the witchcraft trials from Logroño in 1610, adding his burlesque comments.[46] Specialists have doubted this hypothesis by Helman, since Moratín's reissue is well after the Caprichos. In one way or another, however, Goya had access to this or other similar material because the coincidences are pronounced.

Goya in the Witchcrafts satirizes his personal conclusions over feminine inconstancy and the censorship of social vices, now believing in the existence of evil that he expresses in beings of repulsive ugliness. Through an overflowing fantasy, he deforms the features of the faces and bodies of these tragicomic witches, suggesting new forms of malignancy.[45]

Capricho No. 45, Mucho hay que chupar. (There is plenty to suck.);

Capricho No. 44, Hilan delgado. (They spin finely.);

Capricho No. 62, ¡Quién lo creyera! (Who would have thought it!) (Details)

Capricho No. 59, ¡Y aún no se van! (And still they don't go!);

Capricho No. 68, Linda maestra (Pretty teacher);

Capricho No. 71, Si amanece, nos vamos. (When day breaks we will be off.);

Capricho No. 65, ¿Dónde va mamá? (Where is mommy going?) (Details)

A group Goya developed in parallel to that of Witches is that of Elves. The belief in goblins was a minor superstition; goblins did not inspire terror and were seen in a familiar, festive and mocking way. Furthermore, in the second half of the 18th century the word “duende” often meant “friar,” which explains why Goya's duendes are dressed in religious habits. Goya initially seems to treat friars just as the goblins who were perceived as harmless characters. But as the pictures progress, friars transform into sinister beings whose activities are far from harmless.

According to the Ayala and National Library manuscripts that interpret the Caprichos, Goya's intention would be to point out that the true goblins are the priests and friars who eat and drink at our expense and who outstretch their hands to take.[47]

Capricho No. 74, No grites, tonta. (Don't scream, stupid.);

Capricho No. 79, Nadie nos ha visto. (No one has seen us.);

Capricho No. 80, Ya es hora. (It is time.) (Details)

Capricho No. 70, Devota profesión (Devout profession);

Capricho No. 46, Corrección (Correction);

Capricho No. 49, Duendecitos (Hobgoblins);

Capricho No. 52, ¡Lo que puede un sastre! (What a tailor can do!) (Details)

Chronologically, according to Camón Aznar, are three stages in the development of these Caprichos. The earliest is the least consequential, within the aesthetic climate of Goya's latest cartoons with a predominance of majas and love affairs. They are the result of personal experiences, marked by the obsessive memory of the Duchess of Alba. In the second stage the surfaces are lightened, sharply highlighting the figures; the world is viewed with skepticism and the satire becomes merciless with more bestial characters. The third stage of execution, coinciding with the plates starting with Capricho No. 43, corresponds to the world of delusions with monstrous beings.[48]

Technique

editThe engravings of Goya and Rembrandt have been compared; it is known that the Aragonese painter had prints by the Dutchman. The differences between the two are pointed out by M. Paul-André Lemoisne: Rembrandt mastered the craft of an engraver, usually beginning his sketches directly on the plate, just as painter-engravers do. Goya, on the other hand, first drew the subject on paper. Goya's drawings are generally meticulous; when he engraved them, he simplified and lightened them, thus his etchings are brighter than the drawings. Goya seems to have limited his engraving technique without trying to develop it. He did not use the cross carving of the etching, and used a single type of aquatint to uniformly fill the entire background of the print[49]

This is how Félix Boix characterized Goya's style: the peculiar and original effect of the Caprichos plates is achieved by associating the etching with flat and uniform aquatints, often very intense, especially in the backgrounds and with degraded aquatints to achieve different tones in the modeling of clothing, figures and accessories. The highlights in the washes were achieved with the burnisher, achieving stain and chiaroscuro effects more quickly than with etching alone.[50]

To transfer the drawing to the plate and avoid making it inverted, Goya placed the moistened drawing on the copper and pressed it, leaving on the copper the main lines marked and leaving on the paper the ink slightly smudged around its contour, an appearance perceptible today.[51]

The form of lighting is totally arbitrary in these prints. Goya used light effects to highlight areas of maximum expressiveness, resulting in totally artificial and inaccurate lighting. Using aquatints he achieved very strong contrasts in the composition, since his blacks violently highlight the lights, producing highly dramatic effects. He also used aquatints to give each figure different emotional effects through different intonations of gray, thus grading the emotional effects of each character in the group.[52]

The drawing

editPreparatory drawings were created in a three-phase process, though some drawings did not involve all three phases and others used all three phases on the same drawing. The first phase, the idea or inspiration, was developed with a wash brush, either in black or red. In the second phase, the expressions and details were specified and intensified with red pencil. The third phase consisted of a detailed sketch with pen, with all the precise shading and features.[53]

The transition to engraving does not have a uniform method either, but Goya systematically retouched, seeking to highlight his message. To do this, he sometimes deleted characters and accessories from the drawing; other times he augmented and elaborated them. With respect to drawing, he always intensified the expressions of the figures and the effects of chiaroscuro and tried to transform the anecdotal and occasional nature of the initial drawing into a general and universal theme.[53]

It should be noted, however, that the fidelity of the etching to the drawing is great. All the advantages of drawing of forming physiognomies, twisting gestures, and distorting features that are easy to do with the pencil are systematically repeated in engraving with the burin.[53]

Preparatory drawings and Capricho No. 10, El amor y la muerte (Love and death) and Capricho No. 12, A caza de dientes (Out hunting for teeth) (Details)

Preparatory drawings and Capricho No. 17, Bien tirada está. (It is nicely stretched.) and Capricho No. 8, ¡Que se la llevaron! (So they carried her off!) (Details)

Throughout the series, we can see how Goya acquired mastery in transferring drawing to engraving. As Goya grew skilled in the engraving technique, drawing precision was abandoned and became increasingly free and spontaneous, no longer a conscientious initial work that would serve as a basis for later works. Progressively, Goya acquired great freedom of execution.[54]

For the Caprichos Goya was inspired by many themes and compositions from the drawings in Albums A and B (Album A, or Small Notebook from Sanlúcar, was made in the residence of the Duchess of Alba in 1796. Album B, from Sanlúcar-Madrid, was also made in 1796, though other authors believe it made in 1794). [55]

The engraving

editAs described previously, Goya made considerable progress from his prior experience engraving Velázquez's paintings. While he masterfully used etching, he used aquatint for the backgrounds.[13]

Etching consists of spreading a small layer of varnish on the copper plate, then using a chisel or a steel tip like a pencil to lift the varnish from the areas where the tip passes. Then the acid, or etching is spread, attacking only the areas not protected by the varnish that were lifted with the tip. Then the plate is inked, with ink only penetrating the acid-burned areas; a damp paper is placed on the plate; and the paper is passed through the rollers, leaving the stamp engraved.[22]

Aquatint is a different technique, consisting of spreading a layer of resin powder on the copper plate. As more or less resin is dropped, lighter or darker tones emerge. When heated, the resin adheres to the copper, and when introduced into the acid, the thinner part is burned by the acid with greater intensity, while the rest is attacked more weakly.[22]

The Aquatint technique allowed Goya to treat the engraving as if it were a painting, transferring the colors to the entire range from white to black through all the intermediate shades of gray (or red if the engraving is done with red or sepia ink).

Goya did many tests on the condition of the engravings, and when the result did not satisfy him, he retouched the etching or aquatint again and again until he found it satisfactory.[22] Tomás Harris, artist and critic, contributed his specialized knowledge to describe how Goya made his engravings:

"...first he engraved the copper plate, and when he took it out of the acid bath, he took one or two samples of the freshly burned plate. He sometimes retouched these tests with a pen, pencil, or charcoal to guide him in the additions he intended to make on the plate...he took condition tests before and during the aquatint burnishing...he retouched with the drypoint or the burin during each of the steps... Goya used the burnisher and the scraper with extraordinary ease, removing (if it did not please him) from a plate such large areas of aquatint that their original existence is only known to us by an artist's proof... Few test prints have survived, although it is evident that when he used mixed media, he must have taken state tests in the course of engraving."[56]

The legends

editIn the Caprichos, the visual conveys the basic concept the prints are intended to depict; however, the images contain texts greatly relevant for understanding the visual messages. In addition to the suggestive titles of the prints, Goya and his contemporaries left numerous annotations and comments written in proofs and first editions. We also know that in the beginning of the 18th century it was common in gatherings to comment on collections of satirical prints. Some of these opinions have been preserved in the form of handwritten explanations. Thanks to these comments, we know Goya's contemporaries’ opinions about the prints, and therefore the interpretation of them at the time. Almost a dozen handwritten comments are known.[57]

The most important, personal, and defining comment on the engravings, shown below, reflect Goya's thinking. In a comprehensive, yet concise and energetic way, the comments summarize a situation or a topic. Goya's aphorisms follow Gracián's style; they are cutting and abrasive with a foundation of cruel mockery.[58] Sometimes these titles are as ambiguous as the themes, offering first a literal interpretation and second a violent criticism through word games extracted from the jargon of the picaresque.[39]

As to contemporary manuscripts, the most popular ones are referenced below. The manuscript called “Ayala,” owned by that playwright, is perhaps the oldest and least discreet because it does not hesitate to point out professional groups or specific people, such as the queen or Godoy, as objects of the satire. In the Prado manuscript, an unknown hand wrote on the first page: this "explanation of Goya's Caprichos is written in his own hand." However, the literary style of the Prado manuscript does not match the lively and sharp character of Goya's letters, so its authorship is doubted. Cardedera, the first collector of his graphic work, thought that the Royal Calcography was considering printing the Prado’s explanation along with the engravings, but did not do so because the commentary openly criticized the vices of the Court. There is a relationship between the Ayala and Prado manuscripts, since thirty explanations share phrases or expressions verbatim or with small variations. In all probability, one version derives from the other and it may be that Ayala's is the one derived from the Prado's. Both series have been copied and altered over time, resulting in other versions. The manuscript from the National Library that Edith Helman published for the first time in her book Trasmundo de Goya seems to incorporate in parentheses material from the addendums to the Prado manuscript.[59] According to Camón Aznar, the Prado manuscript distorts the Goyaesque intention and serves as a smoke screen that hides the transcendence of the prints, and Ayala's manuscript is markedly anticlerical.[58]

Although Goya emphasized his interest in the universal and the absence of specific criticism, since publication of the Caprichos an attempt has been made to place the satire in the political climate of his time, resulting in speculation personalizing the figures to Queen María Luisa; Godoy; Carlos IV; Urquijo; Morla; the duchesses of Alba, Osuna and Benavente; etc.[58]

Two examples are shown where the impact of titles and contemporary comments can be seen.

In Capricho No. 55, Until Death, an ugly, thin and toothless old woman is getting ready in front of the mirror; deceived by her vanity, she appears happy with what she sees. Next to her and in contrast, a healthy and massive young servant observes her. To highlight the action more, two young people make fun of the farce. The artist reinforces the satire with the hammer blow of the title "Hasta la muerte" (Until death), a devastating sarcasm that completes the scenario.[60]

The commentary on the Prado manuscript says: “She does well to make herself pretty; these are her days; She is seventy-five years old and her friends will come to see her." Ayala’s adds: "The old Duchess of Osuna." Other manuscripts see Queen María Luisa in the vain old woman. It is unlikely that she is the Duchess of Osuna, since this family favored Goya with repeated commissions; as for the queen, it does not seem possible either, since she was 47 years old at the time.[60]

In Capricho No. 51, They spruce themselves up, a monstrous being cuts the nails of a companion, while a third covers the others with his wings. It is difficult with a modern mentality to understand this satire. If we analyze the faces, we may decide that they are plotting something; the one with the stretched neck seems vigilant, little more. Even the title describes the scene contemplated, "They spruce themselves up", they are really polishing themselves, beautifying themselves.

Nor does the Prado manuscript clarify anything: "Having long nails is so harmful that even in witchcraft it is prohibited." However, Goya's contemporaries did see in this scene a fierce satire of the State. Thus, Ayala's manuscript points out that "the thieving employees apologize and cover up for each other." While the manuscript from the National Library in Madrid goes even further: “The employees who steal from the State, help and support each other. Their chief raises his neck upright and shields them with his monstrous wings."[61]

The editions

editUnderstanding of the Caprichos can only be achieved by contemplating each print as its creator intended. To this end, it is necessary to show and analyze each of them.

There are discrepancies among catalogers of Goya's graphic work regarding the number of Caprichos editions, especially those produced in the 19th century. From the second edition onwards, all were made by the Royal National Chalcography, the second according to Carderera being printed between 1821 and 1836; the third in 1853; the fourth and fifth in 1857; the sixth in 1860/1867 and the rest in the 19th century in 1868, 1872, 1873, 1874, 1876, 1877 and 1881.[31]

Two other editions cited by Vindel of 200 copies between 1881-1886 and another 230 copies between 1891-1900 cannot be confirmed, since no documentation exists either for or against.[31]

In the 20th century, an edition was made between 1903 and 1905; a second between 1905 and 1907; a third between 1908 and 1912; a fourth between 1918 and 1928; a fifth in 1929; and the sixth in 1937 during the Government of the Republic. Therefore, in total, there is evidence of twenty editions: one in the 18th century, twelve in the 19th, and seven in the 20th.[31]

The color of ink has varied: slightly reddish in the first edition, and in the following editions sepia, black, or blue was used. The quality and size of the paper varies; in the first edition the sheets were 220x320mm, while some editions of 300x425mm exist.[35]

As editions have been made, scratches and deterioration have appeared on the plates, the aquatints being especially worn.[35]

Modern technology means that it is no longer necessary to print from metal plates to reproduce the images. The copper plates themselves, on which the artist worked directly, were restored in advance of an exhibition in 2024 at the Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando.[63]

Facsimile editions of variable fidelity and quality, not from the original plates, have been made by publishers outside the National Chalcography. Three of the best known or most widespread are: those of the Artistic Editorial Center of Barcelona by M Seguí y Riera in 1884, the French publishing house Jean de Bonnot from 1970, and the Spanish publishing house Planeta from 2006.

Influence

editLos Caprichos have influenced generations of artists from movements as diverse as French Romanticism, Impressionism, German Expressionism or Surrealism.

André Malraux is among the critics who considered Goya one of the precursors of modern art, citing the innovations and ruptures of the Caprichos.

The set has been very influential, not only in the visual arts. Its influence can be seen, for example, in:

- Granados' piano suite Goyescas, a work which has entered the standard piano repertory since its two parts were premiered in 1911 and 1914 respectively. It includes a number called El amor y la muerte (a title shared with Capricho No. 10.)

- Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco's guitar work 24 caprichos de Goya, Op. 195 (1961)

In 1825 there were several copies of the Caprichos in England and France, with only Goya's engraved work known. Delacroix studied and copied many figures from one of these copies in 1824, contributing to the image of Goya as satirical and critical of the hierarchy and moral values of Spanish society that spread in the French romantic period. [64]

Baudelaire's perception of the Caprichos represented a considerable advance in the understanding of Goya. His conception of the modernity of the Spanish painter achieved great dissemination. His article on the Caprichos was published in Le Present (1857), in L'Artiste (1858) and in the collection Curiosités Esthétiques (1868):[65]

"In Spain, an extraordinary man has opened new horizons to the spirit of the comic... sometimes he allows himself to be carried away by violent satire, and sometimes, transcending it, he presents an essentially comic vision of life... Goya is always a great artist and often a terrifying artist...he contributed to that Spanish satirical spirit, fundamentally happy and humorous, which had its day in the time of Cervantes, something much more modern, a quality highly appreciated in the current era, a love for the indefinable, a sense of violent contrasts, of the terrifying nature, of human traits that have acquired animal characteristics... it is strange that this anticlerical should have dreamed so frequently of witches, covens, black magic, children cooking on a spit, and many other things: all the orgies of the world of dreams, all the exaggerations of hallucinogenic images, and in addition, all those young Spanish women, thin and white, that the inevitable witches wash and prepare for their secret pacts or for nocturnal prostitution. The coven of civilization! Light and darkness, reason and unreason, confront each other in all these grotesque horrors!

Charles Baudelaire on Goya's Caprichos in Le Present."[66]

Goya's romantic image passed from France to England, while it remained in Spain. The same thing happened in Germany. It had its peak in the last three decades of the 19th century.[67]

MacColl (1902), an English critic, highlighted Goya's influences on the Impressionists, including him among the precursors of Modern Art: the way in which he captures attention "seems to anticipate half a dozen modern styles"; his intensity and courage are decisive for Manet; his "diabolical inspiration" set the precedent for those of Félicien Rops, Toulouse-Lautrec, and Aubrey Beardsley.[68]

In the last decade of the 19th century, new generations of artists preferred their fantasies less explicit and more suggestive of dreams in the second part of the Caprichos. MacColl, already cited, highlighted the ability of engravings to provoke an emotional response. Thus, he inspired Kandinsky's generation, who had left external contemplation to become introspective. The attraction of Goya's emotional content on the artists and critics of Expressionism at the beginning of the 20th century influenced Nolde, Max Beckmann, Franz Marc, and especially Paul Klee. According to Mayer, Goya's expressionism is seen most strongly in his drawings. Therefore, Los Caprichos, which had been exalted until then for its political and moral symbolism, came to be considered, along with Los Disparates [the Nonsensical], a mysterious and emotional work by the painter.[69]

In the third decade of the 20th century, Surrealism associated the subconscious with works of art. Daniel Gascoyne, in his Brief Study of Surrealism (London, 1935), argued that it had always existed and cited, among others, Goya and El Greco as examples. Some surrealists thought that Goya, as they did, intentionally explored the world of dreams. A selection of the Caprichos was exhibited at the International Surrealist Exhibition in New York in 1936.[70]

Malraux in his essay "Voices of Silence", developed between 1936 and 1951, considered Goya as a central figure in the development of Modern Art. According to Malraux, Goya, in his first caricatures, ignored and destroyed the moralistic style of previous caricaturists. To express himself, he sought his roots in the depths of the subconscious. The artist progressively eliminated the frivolous and decorative lines with which he initially tried to please the public and became stylistically isolated. Los Caprichos, for Malraux, are torn between reality and dream, constituting a kind of imaginary theater.[56]

Gallery

editAs Sánchez Cantón points out in his book on the Caprichos, knowledge of their preparation and the environment in which they were created will enhance enjoyment, hidden or obscure aspects may be examined, and their value as historical documents noted.[71]

-

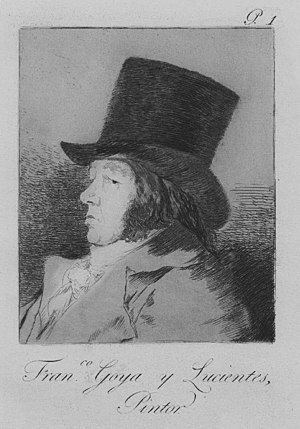

Capricho No. 1: Francisco Goya y Lucientes, pintor (Francisco Goya y Lucientes, painter)

-

Capricho No. 2: El sí pronuncian y la mano alargan al primero que llega (They say yes and give their hand to the first comer)

-

Capricho No. 3: Que viene el coco (Here comes the bogeyman)

-

Capricho No. 4: El de la Rollona (Nanny's boy)

-

Capricho No. 5: Tal para cual (Two of a kind)

-

Capricho No. 6: Nadie se conoce (Nobody knows himself)

-

Capricho No. 7: Ni así la distingue (Even thus he cannot make her out)

-

Capricho No. 8: ¡Que se la llevaron! (So they carried her off!)

-

Capricho No. 9: Tántalo (Tantalus)

-

Capricho No. 10: El amor y la muerte (Love and death)

-

Capricho No. 11: Muchachos al avío (Lads making ready)

-

Capricho No. 12: A caza de dientes (Out hunting for teeth)

-

Capricho No. 13: Están calientes (They are hot)

-

Capricho No. 14: ¡Qué sacrificio! (What a sacrifice!)

-

Capricho No. 15: Bellos consejos (Good advice)

-

Capricho No. 16: Dios la perdone: y era su madre (For Heaven's sake: and it was her mother)

-

Capricho No. 17: Bien tirada está (It is nicely stretched)

-

Capricho No. 18: Y se le quema la casa (And the house is on fire)

-

Capricho No. 19: Todos caerán (Everyone will fall)

-

Capricho No. 20: Ya van desplumados (There they go plucked)

-

Capricho No. 21: ¡Cual la descañonan! (How they pluck her!)

-

Capricho No. 22: ¡Pobrecitas! (Poor little girls!)

-

Capricho No. 23: Aquellos polvos (Those specks of dust)

-

Capricho No. 24: No hubo remedio (There was no help)

-

Capricho No. 25: Si quebró el cántaro (He broke the pitcher)

-

Capricho No. 26: Ya tienen asiento (Now they are sitting well)

-

Capricho No. 27: ¿Quién más rendido? (Who surrendered more?)

-

Capricho No. 28: Chitón (Hush)

-

Capricho No. 29: Esto sí que es leer (Now that's reading)

-

Capricho No. 30: ¿Por qué esconderlos? (Why hide them?)

-

Capricho No. 31: Ruega por ella (She prays for her)

-

Capricho No. 32: Porque fue sensible (Because she was susceptible)

-

Capricho No. 33: Al conde palatino (To the count palatine)

-

Capricho No. 34: Las rinde el sueño (Sleep overcomes them)

-

Capricho No. 35: Le descañona (She fleeces him)

-

Capricho No. 36: Mala noche (A bad night)

-

Capricho No. 37: ¿Si sabra más el discípulo? (Might not the pupil know more?)

-

Capricho No. 38: ¡Bravísimo! (Bravissimo!)

-

Capricho No. 39: Hasta su abuelo (And so was his grandfather)

-

Capricho No. 40: ¿De qué mal morirá? (Of what ill will he die?)

-

Capricho No. 41: Ni más ni menos (Neither more nor less)

-

Capricho No. 42: Tú que no puedes (Thou who cannot)

-

Capricho No. 43: El sueño de la razón produce monstruos (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters)

-

Capricho No. 44: Hilan delgado (They spin finely)

-

Capricho No. 45: Mucho hay que chupar (There is plenty to suck)

-

Capricho No. 46: Corrección (Correction)

-

Capricho No. 47: Obsequio al maestro (A gift for the master)

-

Capricho No. 48: Soplones (Snitches)

-

Capricho No. 49: Duendecitos (Hobgoblins)

-

Capricho No. 50: Los Chinchillas (The Chinchillas)

-

Capricho No. 51: Se repulen (They spruce themselves up)

-

Capricho No. 52: ¡Lo que puede un sastre! (What a tailor can do!)

-

Capricho No. 53: ¡Que pico de oro! (What a golden beak!)

-

Capricho No. 54: El vergonzoso (The shameful one)

-

Capricho No. 55: Hasta la muerte (Until death)

-

Capricho No. 56: Subir y bajar (To rise and to fall)

-

Capricho No. 57: La filiación (The filiation)

-

Capricho No. 58: Trágala, perro (Swallow it, dog)

-

Capricho No. 59: ¡Y aún no se van! (And still they don't go!)

-

Capricho No. 60: Ensayos (Trials)

-

Capricho No. 61: Volavérunt (They have flown)

-

Capricho No. 62: ¡Quién lo creyera! (Who would have thought it!)

-

Capricho No. 63: ¡Miren que graves! (Look how solemn they are!)

-

Capricho No. 64: Buen viaje (Bon voyage)

-

Capricho No. 65: ¿Dónde va mamá? (Where is mommy going?)

-

Capricho No. 66: Allá va eso (There it goes)

-

Capricho No. 67: Aguarda que te unten (Wait till you've been anointed)

-

Capricho No. 68: Linda maestra (Pretty teacher)

-

Capricho No. 69: Sopla (Gust the wind)

-

Capricho No. 70: Devota profesión (Devout profession)

-

Capricho No. 71: Si amanece, nos vamos (When day breaks we will be off)

-

Capricho No. 72: No te escaparás (You will not escape)

-

Capricho No. 73: Mejor es holgar (It is better to be lazy)

-

Capricho No. 74: No grites, tonta (Don't scream, stupid)

-

Capricho No. 75: ¿No hay quién nos desate? (Can't anyone unleash us?)

-

Capricho No. 76: Está vuestra merced... pues, como digo... ¡eh! ¡cuidado! si no... (You understand?... Well, as I say... eh! Look out! Otherwise...)

-

Capricho No. 77: Unos a otros (What one does to the other)

-

Capricho No. 78: Despacha, que despiertan (Be quick, they are waking up)

-

Capricho No. 79: Nadie nos ha visto (No one has seen us)

-

Capricho No. 80: Ya es hora (It is time)

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Simon, Linda, "The Sleep of Reason", The World and I

- ^ Gudiol, José (1984). Goya. Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa, S.A. p. 20. ISBN 9788434304048.

- ^ Glendinning 1982, p. 40.

- ^ Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E.; Gallego, Julián (1994). "Goya grabador". Fundación Juan March: 12.

- ^ Pérez Sánchez & Gallego 1994, p. 12.

- ^ Glendinning, Nigel (1992). La década de los Caprichos. Retratos. 1792 - 1804. Madrid: Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. pp. 24–25. ISBN 84-87181-10-4.

- ^ Licht, Fred (2001). Goya Tradición y modernidad. Madrid: Ediciones Encuentro SA. p. 14. ISBN 84-7490-610-5.

- ^ Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. (1988). Goya y la Ilustración. Goya y el espíritu de la Ilustración. Madrid: Museo del Prado. p. 23. ISBN 84-86022-28-2.

- ^ López-Rey, José (1947). Goya y el mundo a su alrededor. Buenos Aires: Editorial Sudamericana.

- ^ Licht 2001, pp. 132–133.

- ^ Helman, Edith (1970). Jovellanos y Goya. Madrid: Taurus Ediciones, S.A. p. 114. ISBN 8430620397.

- ^ a b Pérez Sánchez & Gallego 1994, p. 13.

- ^ a b c Pérez 1994, p. 55.

- ^ Sayre 1988, pp. 112–113.

- ^ "The Sleep of Reason".

- ^ a b Barrena, Clemente; Blas, Javier; Matilla, José Manuel; Villar, José Luís; Villena, Elvira (1994). «Dibujos y Estampas». Goya. Los Caprichos. Dibujos y Aguafuertes. Capricho 43. Central Hispano: Gabinete de Estudios de la Calcografía. R.A.de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. ISBN 84-604-9323-7.

- ^ a b c Sayre 1988, p. 114.

- ^ a b c Camón Aznar 1980, p. 39.

- ^ Cano 1999, p. 114.

- ^ a b Cano 1999, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Camón Aznar 1980, p. 34.

- ^ a b c d Carrete Parrondo 1996, pp. 94–97.

- ^ Cano 1999, p. 147.

- ^ Sayre1988, p. 115.

- ^ a b c d Sayre, Eleanor A. (1988). Goya y el espíritu de la Ilustración. Madrid: Museo del Prado. pp. 112–113. ISBN 84-86022-28-2.

- ^ Carrete Parrondo, Juan (1994). «Francisco de Goya. Los Caprichos». Goya. Los Caprichos. Dibujos y Aguafuertes. Madrid: Central Hispano. R.A.de Bellas Artes de San Fernando. Calcografía Nacional. p. 115. ISBN 84-604-9323-7.

- ^ Camón Aznar 1980, p. 38.

- ^ Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. (1994). «Caprichos». Goya grabador. Fundación Juan March.

- ^ Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. (1988). . «Goya y la Ilustración». Goya y el espíritu de la Ilustración. Madrid: Museo del Prado. p. 18. ISBN 84-86022-28-2.

- ^ Casariego, Rafael (1988). Francisco de Goya, Los Caprichos. Madrid: Ediciones de arte y bibliofilia. p. 1. ISBN 84-86630-11-8.

- ^ a b c d Cano 1999, p. 148.

- ^ Carrete Parrondo 1994, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Camón Aznar 1980, p. 35.

- ^ Sayre 1988, p. 116.

- ^ a b c d Casariego 1988, pp. 37–42.

- ^ Pérez 1994, p. 56-57.

- ^ a b Casariego 1988, p. 1.

- ^ Licht 2001, pp. 133–134.

- ^ a b Helman 1970, p. 175.

- ^ Camón Aznar 1980, p. 55.

- ^ a b Camón Aznar 1980, p. 63.

- ^ Camón Aznar 1980, p. 71.

- ^ Helman, Edith (1983). Trasmundo de Goya. Madrid: Alianza editorial. pp. 106–109. ISBN 84-206-7032-4.

- ^ Helman 1983, pp. 106–109.

- ^ a b Camón Aznar 1980, pp. 78–79.

- ^ Helman 1970, pp. 161–170.

- ^ Helman 1983, pp. 170–172.

- ^ Camón Aznar 1980, pp. 52–53.

- ^ Sánchez Cantón 1949, p. 51.

- ^ Sánchez Cantón 1949, pp. 50–51.

- ^ Sánchez Cantón 1949, p. 49.

- ^ Camón Aznar 1980, p. 46.

- ^ a b c Camón Aznar 1980, pp. 46–49.

- ^ Vega, Jesús (1996). Goya y el dibujo. Goya, 250 años después. Ibercaja. p. 156. ISBN 84-8324-017-3.

- ^ Cano 1999, pp. 112–115.

- ^ a b Glendinning 1982, pp. 171–173.

- ^ Carrete Parrondo, Juan; Centella Salamero, Ricardo (1999). Palabras Preliminares. Mirar y leer los Caprichos de Goya. Zaragoza: Diputación Provincial de Zaragoza, Real Academia de San Fernando, Calcografía Nacional y Museo de Pontevedra. pp. 13–14. ISBN 978-84-89721-62-3.

- ^ a b c Camón Aznar 1980, p. 50.

- ^ Sayre 1988, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Helman 1983, pp. 63–64.

- ^ Helman 1983, p. 223.

- ^ Helman 1970, p. 180.

- ^ "'Caprichos,' 'Disasters,' 'Disparates' and 'Tauromaquia': All of Goya's prints, together for the first time in one exhibition". March 2024.

- ^ Glendinning 1982, pp. 24 and 86.

- ^ Glendinning 1982, p. 99.

- ^ Glendinning 1982, pp. 302–311.

- ^ Glendinning 1982, pp. 112–116.

- ^ Glendinning 1982, p. 142.

- ^ Glendinning 1982, pp. 160–170.

- ^ Glendinning 1982, p. 168.

- ^ Sánchez Cantón 1949, p. 56.

References

editCited sources

edit- Camón Aznar, José (1980). Francisco de Goya, tomo III. Caja de Ahorros de Zaragoza, Aragón y Rioja. Instituto Camón Aznar. ISBN 84-500-5016-2.

- Cano Cuesta, Marina (1999). «Los Caprichos». Goya en la Fundación Lázaro Galdeano. Library Reference No. 84-92-32234-2-6. Madrid: Fundación Lázaro Galdeano.

- Carrete Parrondo, Juan (1996). Goya artista grabador. Creación y difusión. 250 anos despues.

- Glendinning, Nigel (1982). Goya y sus críticos. Madrid: Ediciones Taurus SA. ISBN 84-306-1217-3.

- Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso E. (1994). "«Caprichos». Goya grabador". Fundación Juan March.

- Sánchez Cantón, F.J. (1949). Goya Los Caprichos. Barcelona: Instituto Amatller de Arte Hispánico.

General references

edit- Albert Boime, A Social History of Modern Art. University of Chicago Press, 1991. ISBN 0-226-06335-6.

- John J. Ciofalo, "Quixotic Dreams of Reason." The Self-Portraits of Francisco Goya. Cambridge University Press, 2001.

- Francisco Goya, Los Caprichos. New York: Dover Publications, 1969.

Further reading

edit- Goya in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. 1995. ISBN 9780870997525.

- Stayton, Kevin L. (2014). Brooklyn Museum Highlights. Brooklyn, NY: Brooklyn Museum. p. 141. ISBN 9780872731752.

External links

edit- Caprichos (PDF in the Arno Schmidt Reference Library)

- Translation of the 1799 Advertisement for sale of the series

- Pruebas de estado

- Media related to Los caprichos at Wikimedia Commons