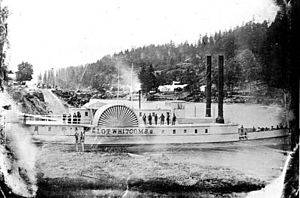

Launched in 1850, Lot Whitcomb, later known as Annie Abernathy, was the first steam-powered craft built on the Willamette River in the U.S. state of Oregon.[1] She was one of the first steam-driven vessels to run on the inland waters of Oregon, and contributed to the rapid economic development of the region.

Lot Whitcomb

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Lot Whitcomb |

| Route | Columbia River, Willamette River, San Francisco Bay, Sacramento River |

| Launched | December 25, 1850 |

| In service | 1851 |

| Out of service | 1868 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | inland steamship |

| Tonnage | 600 |

| Length | 160 ft (49 m) |

| Beam | 24 ft (7 m) |

| Draught | 3 ft (0.91 m) |

| Depth | 5.8 ft (2 m) depth of hold |

| Decks | three (boiler (or cargo), passenger, hurricane) |

| Installed power | single-cylinder walking beam steam engine, 17" bore, 84" stroke, 140 horsepower. |

| Propulsion | sidewheels |

| Speed | about 12 miles an hour |

She later served for many years on the Sacramento River.

Plan for economic development

editLot Whitcomb was built at Milwaukie, Oregon, on the Willamette River. Her initial owners were S.S. White, Berryman Jennings, and Lot Whitcomb, who conceived the steamer as a way to establish Milwaukie, then engaged in rivalry with Portland and other towns along the river, as the premier city in the region. As construction continued, the original owners sold shares in the vessel to various people in the area, and some of the stock was paid for in livestock or produce, which was in turn consumed by the workmen building the vessel, whose wages were mostly in arrears. Lot Whitcomb himself had mortgaged just about everything he had to raise the funds to build the ship.[1]

Construction

editDesign

editLot Whitcomb was built in the tradition of Hudson River steamboats, with some influence from the Mississippi style. (The distinctive Columbia River type of boat would not emerge for about another 8 years.) She had twin boilers set well forward, with twin stacks. Her pilot house was set aft of the stacks. Her sidewheels were set well aft, with large wheel housings extending well above the hurricane deck. Unlike many of the Mississippi boats, Lot Whitcomb was plain without much ornament, and painted completely white, with her name in large letters on the paddlewheel housings. She had a ladies cabin and dining hall, two things which her rival Columbia lacked. The vessel's pilot house was set above the Texas, and was nearly in the middle of the vessel.[2]

Dimensions and machinery

editThe vessel was 160 ft (49 m) long, 24 ft (7 m) on the beam, with 5.7 ft (2 m) depth of hold. Her paddlewheels were 18 ft (5 m) in diameter. She had a single cylinder walking-beam steam engine, with a 17" bore and an 84" stroke.[3] The engine generated 140 horsepower, which could drive the vessel at a rate of about 12 miles per hour.[2] The machinery was brought out to the west coast from New Orleans and was originally intended to power a steamboat on the Sacramento River.

When the equipment arrived in San Francisco, White and his associates bought (paying $15,000[1]) before it was unloaded and arranged to have it shipped to Oregon. The boiler also was built on the east coast, and was shipped west in 21 pieces. When it arrived in Oregon, Jacob Kamm and his assistant not only had to put the boiler together, but they had to make the tools to do the assembly.[3] Gross tonnage of the vessel was 600 tons.[2]

Ainsworth chosen as captain

editJohn C. Ainsworth, a steamboat captain from St. Louis, had also come out west. Lot Whitcomb met Ainsworth and persuaded him to come up to Oregon to take charge of the new steamboat he was planning to build. Jacob Kamm was the engineer.[3]

Launch at Milwaukie, Oregon

editBy act of the Territorial Legislature, the vessel's official name was to be Lot Whitcomb of Oregon.[2] She was launched on December 25, 1850 with a general celebration. Present for speeches and vote-getting were Oregon's territorial governor, John P. Gaines and Mayor Kilbourne of Milwaukie. The U.S. Army brass band from Fort Vancouver played patriotic tunes, and at 3:00 p.m. that day, the props were knocked out and she slid down the ways into the Willamette River. Unfortunately a tragic accident marred the celebration. Frederick Morse, captain of the schooner Merchantman, then loading lumber from Whitcomb's sawmill, had unloaded an old saluting cannon from his vessel, and was in the process of firing it when it burst. Shrapnel from the destroyed barrel flew through the air and hit Captain Morse in the neck, killing him instantly. No one else was hurt, and the celebration continued unabated for several days.[1]

Lot Whitcomb was hailed as the advent of modernity in Oregon. She flew a big pennant from her bow that read "Independence." Elizabeth Markham, mother of the poet Edwin Markham watched Lot Whitcomb ascending the Clackamas Rapids, then a significant obstacle on the route to Oregon City and wrote her own poem in the style of the times that was promptly published in the Oregon Spectator:

Lot Whitcomb is coming!

Her banners are flying--

She walks up the rapids with speed.

She ploughs through the water.

Her steps never falter.

Oh that's independence indeed![2]

Operations on Willamette and Columbia

editThe first outing of the Lot Whitcomb was a pleasure expedition to Astoria. There was a problem running her on the Columbia River, and that was that she still had creditors that hadn't been paid who had an interest in the vessel. American law did not then allow a vessel to operate without a certificate and a certificate could not be lawfully issued if creditors had unpaid claims against the vessel. Worse yet, the official in charge of enforcing this law was the Astoria customs inspector, General Adair, who was a co-owner the Columbia, the only other steamboat on the Columbia River at the time, and as such the chief rival of Lot Whitcomb. More stock was sold to pay off the ship's debts, and regularized operations were finally able to begin.[1]

Lot Whitcomb ran twice weekly on the route from Milwaukie to Astoria, making the run in 10 hours, a substantial improvement over the previous time set by the Columbia which was 24 hours.[2] Columbia charged $25 fare for the run from Portland to Astoria, but under pressure from Lot Whitcomb was forced to drop this first to $15 per person, and later to $12. For a while, the owners of Lot Whitcomb as Milwaukie boosters, refused to stop at Portland. Portland's city founders retaliated by raising $60,000 and then buying the Gold Hunter, an actual ocean-going vessel, to come north to the Columbia River, where she ran for about a year against the Whitcomb. Shortly after launching, Lot Whitcomb struck a rock near Milwaukie, sustained damage to her paddle wheel and a hole in her hull. The vessel was hung up for a week until her owners and the resourceful Captain Ainsworth were able to pull her off and repair her. She also functioned well as a tow boat, escorting many oceangoing ships from Astoria up the Columbia and Willamette rivers to Portland.[3]

Lot Whitcomb's agent in Oregon City was George Abernethy a former territorial governor of Oregon and a prominent early pioneer businessman.

Transfer to California

editLot Whitcomb proved expensive to operate, so a decision was made to sell her to the California Steam Navigation Company. On August 12, 1854 the famous Columbia Bar pilot Captain George Flavel took her out into the Pacific Ocean. The steamship Peytonia towed her down to San Francisco. Captain Ainsworth went along on the trip, which encountered rough weather. By the time they reached San Francisco, Lot Whitcomb had three feet of water in her hold. Once in California, Lot Whitcomb was pumped out, renamed Annie Abernathy and ran until 1868 on the Sacramento River.[4]

Notes

edit- ^ a b c d e Corning, Howard McKinley (1973). Willamette Landings -- Ghost Towns of the River (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society. pgs. 24-27. ISBN 0875950426.

- ^ a b c d e f Mills, Randall V. (1947). Sternwheelers up Columbia -- A Century of Steamboating in the Oregon Country. Lincoln NE: University of Nebraska. 17–23, 121. ISBN 0-8032-5874-7. LCCN 77007161.

- ^ a b c d Wright, E.W., ed. (1895). Lewis & Dryden's Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Portland, OR: Lewis and Dryden Printing Co. 29–31. LCCN 28001147.

- ^ MacMullen, Jerry (1944). Paddlewheel Days in California. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. pgs. 120, 135. ISBN 9780804703826.

References

editBooks

edit- Corning, Howard McKinley (1973). Willamette Landings -- Ghost Towns of the River (2nd ed.). Portland, OR: Oregon Historical Society. ISBN 0875950426.

- MacMullen, Jerry (1944). Paddlewheel Days in California. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press. ISBN 9780804703826.

- Mills, Randall V. (1947). Sternwheelers up Columbia -- A Century of Steamboating in the Oregon Country. Lincoln NE: University of Nebraska. ISBN 0-8032-5874-7. LCCN 77007161.

- Wright, E.W., ed. (1895). Lewis & Dryden's Marine History of the Pacific Northwest. Portland, OR: Lewis and Dryden Printing Co. LCCN 28001147.

On line historic newspaper collections

editExternal links

edit- Media related to Lot Whitcomb (ship, 1850) at Wikimedia Commons