Lubdu, also written as Lubda or Lubdi,[1] was a city in ancient Mesopotamia. It was a provincial center located south of Arrapḫa, modern Kirkuk.[2]

| Alternative name | Lubda, Lubdi |

|---|---|

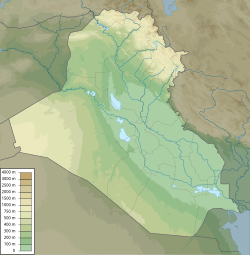

| Location | Possibly Tall Buldāgh, Kirkuk Governorate, Iraq |

| Region | Mesopotamia |

| Coordinates | 35°11′42″N 44°12′05″E / 35.19500°N 44.20139°E |

| Type | Settlement |

Location

editThe exact site is uncertain, but researchers have proposed the mound of Tall Buldāgh (Arabic: تل بلداغ, also transcribed as Tall Buldağ or Tell Buldag) as the possible location of Lubdu.[3] This archeological site is located east of the road from Kirkuk to Tikrit, roughly in the first quarter of the way from the first city to the latter.[4] The attempt of other researchers to locate Lubdu at modern Daquq is rejected by the historian Michael Astour, who argues that the name of Daquq is attested as Diquqina in the Neo-Assyrian period in the same time as Lubdu. Thus, the two were separate cities at a certain distance to each other.[2]

Records

editLubdu was mentioned in the middle of the 15th century BCE in a text on a clay tablet in Hurrian by Itḫi-Tešup, the king of Arrapḫa, where he appeals to a god called Ištar Lu-ub-tu-ḫi. In Hurrian culture, gods were frequently given epiteths of the cities their main temples were in.[2] The inscription is a testament to the importance of early Lubdu, which can be considered a cultic center during that time. Arrapḫa was a vassal kingdom of the Hurrian kingdom Mitanni, which also had chariots stationed in Lubdu.[5]

Later, the Mitanni rule in the area was being challenged by the Babylonians. At some point, Lubdu was taken by the Kassite kingdom of Babylonia, possibly under Burna-Buriaš II during the middle of the 14th century BCE, who waged a successful war against the Mitanni in this area. It then was located at the north-eastern fringes of the Babylonian zone of control and witnessed an influx of Hurrian servile workers.[6]

During the reign of the Assyrian king Adad-nīrārī I (1307–1275), he destroyed the area of Lubdu in his war against the Babylonian king Nazi-maruttaš.[6] In 911 or 910 BCE, the Assyrian king Adad-nīrārī II conquered the city of Lubdu and Arrapḫa,[7] after defeating the Babylonian king Šamaš-mudammiq.[8] Having captured these cities, which were described as fortresses of Babylonia at that time, he had secured important bridgeheads for further operations in the west and the south.[7]

In 648 BCE, Lubdu is mentioned in a record of the Assyrian king Ashurbanipal. There it is written, that Antarii̯a, a chieftain of Lubdu, had marched out at night to attack the Assyrian cities Ubbumme and Kullimmeri. However, his forces were defeated and his head reportedly brought to Ashurbanipal in Nineveh.[9] The historian A.C. Piepkorn identified Antarii̯a not as an independent chieftain but a governor of Urartu. The Assyriologist Ignace Gelb added that the name of Antarii̯a is likely of Hurrian origin.[1]

Notes

edit- ^ a b Gelb, Ignace (1944). Hurrians and Subarians (PDF). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 83. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ a b c Astour, Michael C. (1987). Studies on the Civilization and Culture of Nuzi and the Hurrians - Volume 2. Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns. p. 51f. ISBN 978-0-931464-08-9. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ Bagg, Ariel M. (2015). "Reviewed Work: Siedlungsgeschichte im mittleren Osttigrisgebiet. Vom Neolithikum bis in die neuassyrische Zeit (= Abhandlungen der Deutschen Orient-Gesellschaft 28)". Archiv für Orientforschung. 53: 431. JSTOR 44810859. Retrieved 29 February 2024.

- ^ "Location of Tall Buldagh on Wikimapia". Wikimapia. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ Qader, Asoss M. (2013). Arrapḫa (Kirkuk) von den Anfängen bis 1340 v. Chr. nach keilschriftlichen Quellen (PDF). Würzburg: Universität Würzburg. pp. 121, 124, 173. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ a b Zimmermann, Lynn-Salammbô (2024). "Knocking on Wood: Writing Boards in the Kassite Administration". Journal of Ancient Near Eastern History. 10 (2): 184–185. doi:10.1515/janeh-2023-0010. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ a b Radner, Karen; Moeller, Nadine; Potts, D.T. (2023). The Oxford History of the Ancient Near East Volume IV: The Age of Assyria. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 203. Retrieved 1 March 2024.

- ^ A. K. Grayson (1975). Assyrian and Babylonian chronicles. J. J. Augustin. pp. 208, 243.

- ^ Luckenbill, Daniel David (1927). Ancient Records of Assyria and Babylonia (PDF). Chicago: University of Chicago Press. p. 328.