The Luxembourg Crisis (German: Luxemburgkrise, French: Crise luxembourgeoise) was a diplomatic dispute and confrontation in 1867 between France and Prussia over the political status of Luxembourg.

The confrontation almost led to war between the two parties, but was peacefully resolved by the Treaty of London.

Background

editLuxembourg City boasted some of the most impressive fortifications in the world, the Fortress of Luxembourg, partly designed by Marshal Vauban and improved by subsequent engineers, which gave the city the nickname "Gibraltar of the North". Since the 1815 Congress of Vienna, the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg had been in personal union with the Kingdom of the Netherlands. In a concession to neighbouring Prussia, Luxembourg became a member of the German Confederation, with several thousand Prussian soldiers stationed there.[1] The Belgian Revolution of 1830 had divided Luxembourg into two (see Third Partition of Luxembourg), threatening Dutch control of the remaining territory. As a result, William I of the Netherlands entered Luxembourg into the German customs union, the Zollverein, to dilute the French and Belgian cultural and economic influence in Luxembourg.[2]

Austro-Prussian War

editThe Second Schleswig War of 1864 had further advanced nationalist tensions in Germany, and, throughout 1865, it was clear that Prussia intended to challenge the position of the Austrian Empire within the German Confederation. Despite potentially holding the balance of power between the two, Emperor Napoleon III kept France neutral. Although he, like most of Europe, expected an Austrian victory, he could not intervene on Austria's side as that would jeopardise France's relationship with Italy post-Risorgimento.

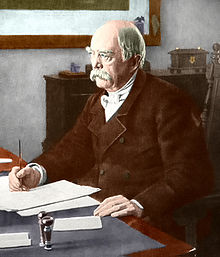

As a result, at Biarritz on 4 October 1865, Napoleon III promised Prussian Prime Minister, Otto von Bismarck, France's neutrality, hoping that such an open statement of intent would strengthen France's negotiating position regarding the western bank of the Rhine. Bismarck refused to offer any land from the Rhineland, which was Napoleon's preferred region. However, he did make suggestions of French hegemony in Belgium and Luxembourg, although not committing anything to writing.[3]

When Austria and Prussia did go to war in 1866 (the so-called Seven Weeks' War), the result was a shock to Europe. Prussia quickly defeated Austria and her allies, forcing Austria to the negotiating table. Napoleon III offered to mediate, and the result, the Treaty of Prague, dissolved the German Confederation in favour of a Prussian-dominated organisation, the North German Confederation.

French offer

editAssuming that Bismarck would honour his part of the agreement, the French government offered King William III of the Netherlands 5,000,000 guilders for Luxembourg. Being in deep financial trouble, William accepted the offer on 23 March 1867.

But the French were shocked to learn that Bismarck now objected. There was a public outcry against the deal in Germany; Bismarck's hand was forced by nationalistic newspapers in north Germany.[4] He reneged on the pledge that he had made to Napoleon at Biarritz, and threatened war. Not only had Bismarck united much of northern Germany under the Prussian crown, but he had secretly concluded agreements with the southern states on 10 October.

To avert a war that might drag their own countries into conflict, other countries rushed to offer compromise proposals. Austria's Foreign Minister, Count Beust, proposed transferring Luxembourg to neutral Belgium, in return for which France would be compensated with Belgian land. However, King Leopold II of Belgium refused to part with any of his lands, putting paid to Beust's proposal.[4]

With the German public angered and an impasse developing, Napoleon III sought to backtrack; he certainly did not want to appear to be unduly expansionist to the other Great Powers. Thus, he demanded only that Prussia withdraw its soldiers from Luxembourg City, threatening war if Prussia did not comply. To avoid this fate, Emperor Alexander II of Russia called for an international conference, to be held in London.[4] The United Kingdom was more than happy to host the talks as the British government feared that the absorption of Luxembourg by either power would weaken Belgium, its strategic ally on the continent.[5]

London Conference

editAll of the Great Powers were invited to London to hammer out a deal that would prevent war. As it was clear that no other power would accept the incorporation of Luxembourg into either France or the North German Confederation, negotiations centred upon the terms of Luxembourg's neutrality. The result was a victory for Bismarck; although Prussia would have to remove its soldiers from Luxembourg City, Luxembourg would remain in the Zollverein.

The Luxembourg Crisis showed the influence public opinion could have on the actions of governments. It also demonstrated the growing opposition between France and Prussia and foreshadowed the Franco-Prussian War which would break out in 1870.

For Luxembourg, this was an important step towards full independence, despite the fact that it remained united in a personal union with the Netherlands until 1890. Luxembourg was provided an opportunity to develop itself independently, leading to the emergence of the steel industry in the south of the country.

In the Netherlands, there was criticism from parliament against the king and government, especially against Foreign Affairs minister Jules van Zuylen van Nijevelt. The liberals found the actions from the king and cabinet had endangered Dutch neutrality and almost dragged the country into a European war. Parliament blocked the budget of the Foreign Affairs department and, when the irritated king disbanded the parliament, the new parliament confirmed this and demanded the dismissal of the government. The king and government concurred, and the unwritten rule of confidence was created in Dutch state law: a minister or government could rule only with support of (a majority in) parliament.

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Trausch 1983, p. 53.

- ^ Calmes 1989, pp. 325–7.

- ^ Fyffe 1895, ch. XXIII.

- ^ a b c Fyffe 1895, ch. XXIV.

- ^ Moose 1958, pp. 264–5.

References

edit- Moose, Werner Eugen (1958). The European Powers and the German Question, 1848-71. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Calmes, Christian (1989). The Making of a Nation From 1815 to the Present Day. Luxembourg City: Saint-Paul.

- Fyffe, Charles Alan (1895). A History of Modern Europe, 1792-1878. Retrieved 2006-06-27.

- Trausch, Gilbert (1983). "Blick in die Geschichte". Das ist Luxemburg (in German). Stuttgart: Seewald-Verlag.