Lynn is the eighth-largest municipality in Massachusetts, United States,[8] and the largest city in Essex County. Situated on the Atlantic Ocean, 3.7 miles (6.0 km) north of the Boston city line at Suffolk Downs, Lynn is part of Greater Boston's urban inner core.[9]

Lynn | |

|---|---|

City | |

Downtown Lynn | |

| Nicknames: "City of Sin" and "City of Firsts" | |

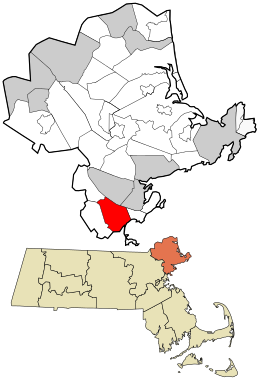

Location in Essex County and Massachusetts. | |

| Coordinates: 42°28′N 70°57′W / 42.467°N 70.950°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Massachusetts |

| County | Essex |

| Settled | 1629 |

| Incorporated (Town) | 1629 |

| Named | 1637[1] |

| Incorporated (City) | May 14, 1850[2][3] |

| Named for | King's Lynn, Norfolk, England[1] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council city |

| • Body | Executive Branch (Mayor) and Legislative Branch (City Council)[4] |

| • Mayor[5] | Jared C. Nicholson (D) |

| • Council[6] | John M. Walsh Jr (President, Ward 7) (D) Dianna Chakoutis (Vice President, Ward 5) (D) Brian M. Field (at-large) (D) Brian P. LaPierre (at-large) (D) Hong L. Net (at-large) (D) Nicole McClain (at-large) (D) Peter Meany (Ward 1) (D) Obed Matul (Ward 2) (D) Constantino “Coco” Alinsug (Ward 3) (D) Natasha Megie-Maddrey (Ward 4) (D) Frederick W. Hogan (Ward 6) (D) |

| Area | |

• Total | 13.52 sq mi (35.02 km2) |

| • Land | 10.74 sq mi (27.81 km2) |

| • Water | 2.78 sq mi (7.20 km2) |

| Elevation | 30 ft (9 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• Total | 101,253 |

| • Density | 9,428.53/sq mi (3,640.41/km2) |

| Demonym | Lynner |

| Time zone | UTC−5 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−4 (Eastern) |

| ZIP Codes | 01901–01905 |

| Area codes | 339/781 |

| FIPS code | 25-37490 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0613376 |

| Website | www |

Settled by Europeans in 1629, Lynn is the 5th oldest colonial settlement in the Commonwealth.[10] An early industrial center, Lynn was long colloquially referred to as the "City of Sin", owing to its historical reputation for crime and vice. Today, however, the city is known for its contemporary public art,[11][12][13][14] immigrant population, historic architecture, downtown cultural district, loft-style apartments, and public parks and open spaces,[15] which include the oceanfront Lynn Shore Reservation; the 2,200-acre, Frederick Law Olmsted-designed Lynn Woods Reservation; and the High Rock Reservation and Park designed by Olmsted's sons.[16] Lynn also is home to Lynn Heritage State Park,[17] the southernmost portion of the Essex Coastal Scenic Byway,[18] and the seaside, National Register-listed Diamond Historic District.[19] The population was 101,253 at the 2020 United States census.[20]

History

editPre-contact

editThe area that is now known as Lynn was inhabited for thousands of years by Native Americans prior to English colonization in the 1600s. At the time of European contact, the area today known as Lynn was primarily inhabited by the Naumkeag people[21] under the powerful sachem Nanepashemet who controlled territory from the Mystic to the Merrimack Rivers. Colonists would not establish a legal agreement with the Naumkeag over the use of their land in Lynn until 1686 after a smallpox epidemic in 1633, King Philip's War, and missionary efforts significantly reduced their numbers and confined them to the Praying Town of Natick.[21]

17th century

editEnglish colonists settled Lynn not long after the 1607 establishment of Jamestown, Virginia and the 1620 arrival of the Mayflower at Plymouth.[22] European settlement of the area was begun in 1629 by Edmund Ingalls, followed by John Tarbox of Lancashire in 1631. The area today encompassing Lynn was originally incorporated in 1629 as Saugus, the Massachusett name for the area. Three years after the settlement in Salem, five families moved onto Naumkeag lands in the interior of Lynn, then known as Saugus, and the Tomlin family constructed a large mill between today's Sluice and Flax Ponds. The mill not only supplied grains and sustenance for the settlers and trade with the Naumkeag people, but was used to create brews and many fermented casks of hops and wines to send back to King George in England.[citation needed]

Lynn takes its name from King's Lynn, Norfolk, England, in honor of Reverend Samuel Whiting (Senior), Lynn's first official minister who arrived from King's Lynn in 1637.[1][23]

A noteworthy early Lynn colonist, Thomas Halsey, left Lynn to settle the East End of Long Island, where he and several others founded the Town of Southampton, New York. The resulting Halsey House—the oldest extant frame house in New York State (1648)—is now open to the public, under the aegis of the Southampton Colonial Society.[24]

As English settlement pushed deeper into Naumkeag territories, disease, missionary efforts, and loss of access to seasonal hunting, farming, and fishing grounds caused significant disruption to Naumkeag lifeways. In 1675, Naumkeag sachem Wenepoykin joined Metacomet in resisting English colonization in King Philip's War, for which he was enslaved and sent to Barbados.[21] In 1686, under pressure to demonstrate legal title for lands they occupied during the administrative restructuring of the Dominion of New England, the selectmen of Lynn and Reading purchased a deed from Wenopoykin's heirs Kunkshamooshaw and Quonopohit for 16 pounds of sterling silver,[21] though by this time they and most surviving Naumkeag were residents of the Natick Praying Town.

Further European settlement of Lynn led to several independent towns being formed, with Reading created in 1644; Lynnfield in 1782; Saugus in 1815; Swampscott in 1852; and Nahant in 1853. The City of Lynn was incorporated on May 14, 1850.[2][3]

Colonial Lynn was an early center of tannery and shoe-making, which began in 1635. The boots worn by Continental Army soldiers during the Revolutionary War were made in Lynn, and the shoe-making industry drove the city's growth into the early nineteenth century.[23] This legacy is reflected in the city's seal, which features a colonial boot.[25]

19th century

editIn 1816, a mail stage coach was operating through Lynn. By 1836, 23 stage coaches left the Lynn Hotel for Boston each day. The Eastern Railroad Line between Salem and East Boston opened on August 28, 1838. This was later merged with the Boston and Maine Railroad and called the Eastern Division. In 1847 telegraph wires passed through Lynn, but no telegraph service station was built until 1858.[26]

During the middle of the nineteenth century, estates and beach cottages were constructed along Lynn's shoreline, and the city's Atlantic coastline became a fashionable summer resort.[27] Many of the structures built during this period are today situated within the National Register-listed Diamond Historic District.

Further inland, industrial activity contemporaneously expanded in Lynn. Shoe manufacturers, led by Charles A. Coffin and Silas Abbott Barton, invested in the early electric industry, specifically in 1883 with Elihu Thomson, Edwin J. Houston, and their Thomson-Houston Electric Company.[28] That company merged with Edison Electric Company of Schenectady, New York, forming General Electric in 1892, with the two original GE plants being in Lynn and Schenectady. Coffin served as the first president of General Electric.[29]

Initially the General Electric plant specialized in arc lights, electric motors, and meters. Later it specialized in aircraft electrical systems and components, and aircraft engines were built in Lynn during WWII. That engine plant evolved into the current jet engine plant during WWII because of research contacts at MIT in Cambridge.[30] Gerhard Neumann was a key player in jet engine group at GE in Lynn. The continuous interaction of material science research at MIT and the resulting improvements in jet engine efficiency and power have kept the jet engine plant in Lynn ever since.[citation needed]

One of the largest strikes of the early labor movement began in the shoe factories of Lynn on February 22, 1860, when Lynn shoemakers marched through the streets to their workplaces and handed in their tools, protesting reduced wages.[31] Known as the 1860 New England Shoemakers Strike, it was one of the earliest strikes of its kind in the United States.[citation needed]

In 1841, abolitionist Frederick Douglass, moved to Lynn as a fugitive slave. Douglass wrote his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave, while living in Lynn. The publication would become Douglass's best-known work. Douglass, his wife, and their five children lived in Lynn until 1848.[32]

In 1870, Esther Hill Hawks, a renowned a female physician, and activist during the American Civil War, moved to Lynn becoming one of the three first female physicians in Lynn, providing her gynecology services to many women. Later on in 1874, opening her own practice.

On February 1, 1866, Mary Baker Eddy experienced the "fall in Lynn", often referred to by Christian Scientists as significant to the birth of their religion.[33]

In 1889 a massive fire swept through the downtown of Lynn, and would not be matched in size until nearly 100 years later.[34] At the time the loss was the third largest from fire in New England history. A total of 296 building were destroyed, including 142 homes, 25 stores, the Central Square railroad depot, four banks and four newspaper buildings. It was estimated that 200 families were made homeless and 10,000 jobs were lost. Estimates put the total loss as high as $6,000,000 (equivalent to about $203,470,000 in 2023).[35]

20th century

editLynn experienced a wave of immigration during the late 1800s and early 1900s. During the 30 years between 1885 and 1915, Lynn's immigrant population increased from 9,800 to 29,500, representing nearly one-third of the city's total population.[36] Polish and Russian Jews were the largest single group, numbering more than 6,000.[36] The first Jewish settlers in Lynn, a group of twenty Hasidic European families, mostly from Russia, formed the Congregation Anshai Sfard, a Hasidic, conservative Jewish synagogue in 1888.[37]

Catholic churches catering to the needs of specific language and ethnic groups also testify to the waves of immigrants. St. Jean Baptiste parish, eventually including a grammar school and high school, was founded in 1886, primarily for French-Canadians. Holy Family Church conducted services in Italian beginning in 1922, and St. Michael's church also provided church services and a grammar school for the Polish-speaking community, beginning in 1906.[38] St. Patrick's church and school was a focus of the Irish-American community in Lynn.[39] St. George's Greek Orthodox Church was founded in Lynn in 1905.[40] Later in the 20th century, the city became an important center of greater Boston's Latino community.[41] Additionally, several thousand Cambodians settled in Lynn between 1975 and 1979 and in the early 1980s.[42]

At the beginning of the 20th century, Lynn was the world-leader in the production of shoes. 234 factories produced more than a million pairs of shoes each day, thanks in part to mechanization of the process by an African-American immigrant named Jan Ernst Matzeliger.[43] From 1924 until 1974, the Lynn Independent Industrial Shoemaking School operated in the city.[44][45] However, production declined throughout the 20th century, and the last shoe factory closed in 1981.[46]

In the early 1900s, the Metropolitan District Commission acquired several coastal properties in Lynn and Nahant, in order to create Lynn Shore and Nahant Beach Reservations, and to construct adjoining Lynn Shore Drive.[47] When it opened to the public in 1910, Lynn Shore Drive catalyzed new development along Lynn's coastline, yielding many of the early 20th century structures that constitute a majority of the contributing resources found in the National Register-listed Diamond Historic District.[3]

In 1970, Massachusetts authorized rent control in municipalities with more than 50,000 residents.[48] Voters in Lynn, Somerville, Brookline, and Cambridge subsequently adopted rent control.[48] Voters in Lynn approved a measure to continue rent control measures, which had been in place since February 1972, on November 7, 1972, by a 22,229 to 15,568 margin.[49] On June 4, 1974, the city council, led by mayor David L. Phillips, voted 7–4 in favor of abolishing the existing rent control measures, replacing them with a "Rent Grievance and Elderly Assistance Board."[50][51]

During the late 1970s and early 1980s, Lynn suffered several large fires. On November 28, 1981, a devastating inferno engulfed several former shoe factories, located at Broad and Washington Streets. Seventeen downtown buildings were destroyed in less than twelve hours, with property losses estimated to be totaling at least $35,000,000 (equivalent to about $117,300,000 in 2023). At least 18 businesses were affected, resulting in the estimated loss of 1,500 jobs.[52] The Lynn campus of the North Shore Community College, planning for which was already underway at the time of the fire, now occupies much of the burned area.[53]

Some data suggest a reputation for crime and vice in Lynn.[54][55]

In order to counter its reputation as "the city of sin", Lynn launched a "City Of Firsts" advertising campaign in the early 1990s, which promoted Lynn as having:[citation needed]

- First iron works (1643)[56]

- First fire engine (1654)

- First electric streetcar to operate in Massachusetts[57][56] (November 19, 1888[58][59])

- First American jet engine[56]

- First woman in advertising & mass-marketing – Lydia Pinkham[56]

- First baseball game under artificial light[citation needed]

- First dance academy in the U.S.[citation needed]

- First tannery in the U.S.[60]

- First air mail transport in New England, from Saugus, MA to Lynn, MA[56]

- First roast beef sandwich[citation needed]

- First tulip in the United States, at the Fay Estate near Spring Pond[citation needed]

In a further effort to rebrand the municipality, city solicitor Michael Barry proposed renaming the city Ocean Park in 1997, but the initiative was unsuccessful.[61]

Despite losing much of its industrial base during the 20th century, Lynn remained home to many companies, such as:

- A division of General Electric Aviation, focused on manufacturing jet engines[62]

- West Lynn Creamery (now part of Dean Foods's Garelick Farms unit)

- C. L. Hauthaway & Sons, a polymer producer

- Old Neighborhood Foods, a meat packer

- Lynn Manufacturing, a maker of combustion chambers for the oil and gas heating industry

- Sterling Machine Co.

- Durkee-Mower, makers of "Marshmallow Fluff"[63]

21st century

editIn the early 2000s, the renovation and adaptive re-use of downtown historic structures, together with new construction, launched a revitalization of Lynn, which remains ongoing.[64] Arts, culture, and entertainment have been at the forefront of this revitalization, with new arts organizations, cultural venues, public art projects,[65] and restaurants emerging in the downtown area.[66] In 2012, the Massachusetts Cultural Council named downtown Lynn one of the first state-recognized arts and culture districts in Massachusetts.[67]

In 2015, Massachusetts Governor Charlie Baker established a task force, composed of representatives of multiple state and municipal public agencies, to further Lynn's revitalization.[68]

Formerly vacant industrial buildings continue to be converted into loft spaces,[69] and historic homes, particularly Lynn's Diamond Historic District, are being restored.[70] In 2016, several large land parcels in Lynn were acquired by major developers.[71] In November 2018, construction began on downtown Lynn's first luxury midrise—a 259-unit, 10-story building on Monroe Street.[72][73] in December 2019, ground was broken on a 331-unit waterfront development on Carroll Parkway.[74] Many of the recent and pending large real estate projects in Lynn are Transit-oriented developments, sited within a half-mile of Lynn station, which provides 20-minute train service to North Station.[75]

Lynn's revitalization has been bolstered by the city's emergence as a center of creative placemaking.[76]

In 2017, swaths of the city's downtown were transformed by a series of large-scale murals, painted on buildings by local, national, and international artists, as part of the city's inaugural Beyond Walls festival.[65] Light-based interventions, including projections onto High Rock Tower,[77] the installation of vintage neon signs on downtown buildings, and large-scale LED-illuminations of the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority rail underpasses bisecting Lynn's Downtown,[78] also have been deployed.[14] In 2017, Mount Vernon Street, in the core of the downtown Central Square area, began to host block parties, food trucks, and other special events.[79][80]

In recent years, Lynn has attracted a substantial and growing LGBT population.[81]

In April 2018, The Boston Globe named Lynn one of the "Top spots to live in Greater Boston in 2018."[82]

On August 18, 2021, the new Frederick Douglass Park on Exchange Street was dedicated, directly across the street from the site of the Central Square railroad depot where Douglass was forcibly removed from the train in 1841. The park features a bronze bas-relief sculpture of Douglass.[83] The park had been in the works since at least 2019 when a bill was filed in the Massachusetts Senate to designate the park area and its management by the Massachusetts DCR.[84]

On September 16, 2021, Mayor McGee introduced Vision Lynn, a 20-year comprehensive planning project to expand Lynn's diversity and improve infrastructure further.[85] In the following year and a half, Lynn's Planning Department held many opportunities for Lynners to discuss what they see for the future of the city. On April 10, 2023,[86] a draft of the plan was shared on the planning departments website to allow for greater public comment. After May 15, 2023, the public comment window will be closed and the committee will release a final draft to be endorsed and adopted by the city.

Lynn earned the moniker "Condom Capital of the USA"[87] after Global Protection, a subsidiary of Karex, the world's largest condom manufacturer, relocated to the former Garelick Farms facility.[88]

Top employers

edit| # | Employer | # of employees |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | GE Aerospace | 2,500 |

| 2 | Lynn Public Schools | 1,243 |

| 3 | North Shore Community College | 991 |

| 4 | All Care VNA | 630 |

| 5 | Eastern Bank | 500 |

| 6 | Kettle Cuisine | 500 |

Geography

editAccording to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 13.5 square miles (35 km2), of which 10.8 square miles (28 km2) is land and 2.7 square miles (7.0 km2) (19.87%) is water. Lynn is located beside Massachusetts Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. Lynn's shoreline is divided in half by the town of Nahant, which divides Lynn Harbor to the south from Nahant Bay to the north. The city lies north of the Saugus River, and is also home to several brooks, as well as several ponds, the largest being Breed's Pond and Walden Pond (which has no relation to a similarly named pond in Concord). More than one-quarter of the town's land is covered by the Lynn Woods Reservation, which takes up much of the land in the northwestern part of the city. The city is also home to two beaches, Lynn Beach and King's Beach, both of which lie along Nahant Bay, as well as a boat ramp in Lynn Harbor.

Lynn is located in the southern part of Essex County and is 10 miles (16 km) northeast of Boston and 22 miles (35 km) west-southwest of Cape Ann. The city is bordered by Nahant to the southeast, Swampscott to the east, Salem to the northeast, Peabody to the north, Lynnfield to the northwest, Saugus to the west and Revere (in Suffolk County) to the south. Lynn's water rights extend into Nahant Bay and share Lynn Harbor with Nahant. There is no land connection to Revere; the only connection is the General Edwards Bridge across the Pines River. Besides its downtown district, Lynn is also divided into East Lynn and West Lynn, which are further divided into even smaller areas.

Lynn is loosely segmented into the following neighborhoods:

Central:

- Downtown / Business District

- Central Square

West Lynn:

- Pine Hill

- McDonough Sq./ Barry Park

- Tower Hill / Austin Sq. – Saugus River

- The Commons

- The Brickyard

- Walnut St./Lynnhurst

- Veteran's Village

East Lynn:

- Diamond District / Lynn Shore

- Wyoma Sq.

- The Highlands

- The Fay Estates

- Ward 1 / Lynnfield St.

- Goldfish Pond

- The Meadow / Keaney Park

Climate

editLynn experiences cold, snowy winters and warm, humid summers. The climate is similar to that of Boston.

According to the Köppen climate classification, Lynn has either a hot-summer humid continental climate (abbreviated Dfa), or a hot-summer humid sub-tropical climate (abbreviated Cfa), depending on the isotherm used.

| Climate data for Lynn, 1991–2020 simulated normals (59 ft elevation) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 36.7 (2.6) |

38.7 (3.7) |

45.1 (7.3) |

55.4 (13.0) |

64.9 (18.3) |

74.1 (23.4) |

80.1 (26.7) |

79.3 (26.3) |

73.0 (22.8) |

61.9 (16.6) |

51.6 (10.9) |

42.1 (5.6) |

58.6 (14.8) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 28.8 (−1.8) |

30.6 (−0.8) |

37.0 (2.8) |

47.1 (8.4) |

56.7 (13.7) |

66.0 (18.9) |

72.1 (22.3) |

71.1 (21.7) |

64.6 (18.1) |

53.6 (12.0) |

43.7 (6.5) |

34.5 (1.4) |

50.5 (10.3) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 20.8 (−6.2) |

22.5 (−5.3) |

29.1 (−1.6) |

38.8 (3.8) |

48.6 (9.2) |

58.1 (14.5) |

64.0 (17.8) |

63.0 (17.2) |

55.9 (13.3) |

45.1 (7.3) |

35.8 (2.1) |

27.1 (−2.7) |

42.4 (5.8) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.70 (93.96) |

3.49 (88.76) |

4.66 (118.45) |

4.24 (107.58) |

3.50 (88.79) |

4.03 (102.48) |

3.57 (90.76) |

3.45 (87.61) |

3.63 (92.08) |

4.82 (122.46) |

4.01 (101.79) |

4.74 (120.37) |

47.84 (1,215.09) |

| Average dew point °F (°C) | 18.9 (−7.3) |

19.4 (−7.0) |

24.8 (−4.0) |

34.2 (1.2) |

45.5 (7.5) |

56.1 (13.4) |

62.1 (16.7) |

61.5 (16.4) |

55.6 (13.1) |

44.6 (7.0) |

34.0 (1.1) |

25.2 (−3.8) |

40.2 (4.5) |

| Source: PRISM Climate Group[89] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Year | Pop. | ±% |

|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 2,291 | — |

| 1800 | 2,837 | +23.8% |

| 1810 | 4,087 | +44.1% |

| 1820 | 4,515 | +10.5% |

| 1830 | 6,138 | +35.9% |

| 1840 | 9,367 | +52.6% |

| 1850 | 14,257 | +52.2% |

| 1860 | 19,083 | +33.9% |

| 1870 | 28,233 | +47.9% |

| 1880 | 38,274 | +35.6% |

| 1890 | 55,727 | +45.6% |

| 1900 | 68,513 | +22.9% |

| 1910 | 89,336 | +30.4% |

| 1920 | 99,148 | +11.0% |

| 1930 | 102,320 | +3.2% |

| 1940 | 98,123 | −4.1% |

| 1950 | 99,738 | +1.6% |

| 1960 | 94,478 | −5.3% |

| 1970 | 90,294 | −4.4% |

| 1980 | 78,471 | −13.1% |

| 1990 | 81,245 | +3.5% |

| 2000 | 89,050 | +9.6% |

| 2010 | 90,329 | +1.4% |

| 2020 | 101,253 | +12.1% |

| 2022* | 100,891 | −0.4% |

| * = population estimate. Source: United States census records and Population Estimates Program data.[90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101] Source: U.S. Decennial Census[102] | ||

2020 census

edit| Race / Ethnicity (NH = Non-Hispanic) | Pop 2000[103] | Pop 2010[104] | Pop 2020[105] | % 2000 | % 2010 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 55,630 | 42,969 | 34,536 | 62.47% | 47.57% | 34.11% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 8,165 | 9,494 | 10,735 | 9.17% | 10.51% | 10.60% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 168 | 178 | 115 | 0.19% | 0.20% | 0.11% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 5,686 | 6,210 | 6,822 | 6.39% | 6.87% | 6.74% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 39 | 37 | 28 | 0.04% | 0.04% | 0.03% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 349 | 407 | 1,077 | 0.39% | 0.45% | 1.06% |

| Mixed Race or Multi-Racial (NH) | 2,630 | 2,021 | 3,380 | 2.95% | 2.24% | 3.34% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 16,383 | 29,013 | 44,560 | 18.40% | 32.12% | 44.01% |

| Total | 89,050 | 90,329 | 101,253 | 100.00% | 100.00% | 100.00% |

2010 census

editAs of the census of 2010, there were 90,329 people, 33,310 households, and 20,988 families residing in the city.[106]

The racial makeup of the city was:

- 57.6% White

- 12.8% African American

- 0.7% Native American

- 7.0% Asian

- 0.1% Pacific Islander

- 16.8% from other races

- 5.0% from two or more races

Hispanic or Latino of any race were 32.1% of the population (10.5% Dominican, 6.3% Guatemalan, 5.4% Puerto Rican, 2.8% Salvadoran, 1.7% Mexican, 0.6% Honduran, 0.4% Colombian, 0.4% Spanish, 0.2% Peruvian, 0.2% Cuban).[106]

Cambodians form the largest Asian origin group in Lynn, with 3.9% of Lynn's total population of Cambodian ancestry. Other large Asian groups are those of Vietnamese (1.0%), Indian (0.4%), Chinese (0.3%), and Laotian (0.2%) ancestry.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 24.9% under the age of 18 and 75.1% over 18. Males accounted for 49% and females 51%.[106]

Between 2009 and 2013, the median household income in Lynn was $44,849. The per capita income was $22,982. About 21.0% of the population was considered below the poverty line.[107]

Asian population

editIn 1990 Lynn had 2,993 persons of Asian origin. In 2000 Lynn had 5,730 Asians, an increase of over 91%, making it one of ten Massachusetts cities with the largest Asian populations. In 2000 the city had 3,050 persons of Cambodian origin, making them the largest Asian subgroup in Lynn. That year the city had 1,112 persons of Vietnamese origin and 353 persons of Indian origin. From 1990 to 2000 the Vietnamese and Indian populations increased by 192% and 264%, respectively.[108]

By 2004 the Cambodian community in Lynn was establishing the Khmer Association of the North Shore.[108]

Income

editData is from the 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.[109][110][111]

| Rank | ZIP Code (ZCTA) | Per capita income |

Median household income |

Median family income |

Population | Number of households |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Massachusetts | $35,763 | $66,866 | $84,900 | 6,605,058 | 2,530,147 | |

| Essex County | $35,167 | $67,311 | $84,185 | 750,808 | 286,008 | |

| 1 | 01904 | $33,409 | $80,903 | $91,409 | 18,803 | 6,833 |

| United States | $28,155 | $53,046 | $64,719 | 311,536,594 | 115,610,216 | |

| Lynn | $22,982 | $44,849 | $53,557 | 90,788 | 33,122 | |

| 2 | 01901 | $20,625 | $23,467 | $24,125 | 2,023 | 1,096 |

| 3 | 01902 | $20,391 | $37,275 | $45,276 | 44,827 | 16,528 |

| 4 | 01905 | $19,934 | $42,490 | $42,163 | 25,090 | 8,642 |

Government

editLynn is represented in the state legislature by officials elected from the following districts:[112]

- Massachusetts Senate's 3rd Essex district

- Massachusetts House of Representatives' 8th Essex district

- Massachusetts House of Representatives' 9th Essex district

- Massachusetts House of Representatives' 10th Essex district

- Massachusetts House of Representatives' 11th Essex district

| Year | Democratic | Republican | Third parties | Total Votes | Margin |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2020 | 68.93% 24,662 | 29.14% 10,425 | 1.93% 690 | 35,777 | 39.79% |

| 2016 | 67.51% 22,164 | 28.36% 9,311 | 4.13% 1,355 | 32,830 | 39.15% |

| 2012 | 72.09% 23,124 | 26.54% 8,512 | 1.37% 440 | 32,076 | 45.55% |

| 2008 | 68.18% 20,276 | 29.32% 8,719 | 2.50% 744 | 29,739 | 38.86% |

| 2004 | 69.17% 19,372 | 29.90% 8,373 | 0.94% 262 | 28,007 | 39.27% |

| 2000 | 68.87% 18,836 | 24.78% 6,776 | 6.35% 1,738 | 27,350 | 44.10% |

| 1996 | 67.84% 18,370 | 20.81% 5,634 | 11.36% 3,075 | 27,079 | 47.03% |

| 1992 | 50.43% 15,275 | 24.27% 7,350 | 25.31% 7,665 | 30,290 | 25.12% |

| 1988 | 59.30% 18,540 | 38.96% 12,182 | 1.73% 542 | 31,264 | 20.34% |

| 1984 | 53.90% 17,103 | 45.52% 14,445 | 0.57% 182 | 31,730 | 8.38% |

| 1980 | 49.20% 15,777 | 37.32% 11,966 | 13.48% 4,323 | 32,066 | 11.88% |

| 1976 | 62.24% 21,430 | 33.63% 11,580 | 4.13% 1,422 | 34,432 | 28.61% |

| 1972 | 62.06% 24,124 | 37.28% 14,490 | 0.66% 255 | 38,869 | 24.79% |

| 1968 | 71.93% 28,740 | 23.77% 9,500 | 4.30% 1,718 | 39,958 | 48.15% |

| 1964 | 84.07% 36,671 | 15.54% 6,779 | 0.39% 169 | 43,619 | 68.53% |

| 1960 | 64.73% 31,001 | 34.96% 16,746 | 0.31% 149 | 47,896 | 29.76% |

| 1956 | 49.68% 24,191 | 50.05% 24,368 | 0.27% 131 | 48,690 | 0.36% |

| 1952 | 52.19% 27,460 | 47.24% 24,856 | 0.56% 297 | 52,613 | 4.95% |

| 1948 | 59.36% 27,954 | 37.70% 17,753 | 2.93% 1,382 | 47,089 | 21.66% |

| 1944 | 57.10% 26,578 | 42.60% 19,826 | 0.30% 140 | 46,544 | 14.51% |

| 1940 | 55.84% 26,509 | 43.43% 20,617 | 0.73% 346 | 47,472 | 12.41% |

Arts and culture

editNotable locations

edit- Lynn as of 2022 is home to the Massachusetts Monarchs a minor league basketball team competing in The Basketball League.

- Fraser Field, municipal baseball stadium constructed in the 1940s under the Works Progress Administration. It has housed many minor league baseball teams and a few major league exhibition games for the Boston Red Sox. Currently, it is the home of the North Shore Navigators of the Futures Collegiate Baseball League.

- Manning Field, the municipal football stadium. It is the former site of Manning Bowl (c. 1936 – August 2005).

- Lynn Memorial Auditorium

- Mary Baker Eddy House

- Lucian Newhall House

- Grand Army of the Republic Hall (Lynn, Massachusetts)

- Lynn Museum & Historical Society

- Lynn Community Television

- Capitol Diner

- Lynn Masonic Hall

- St. Stephen's Memorial Episcopal Church

Parks and recreation

editLynn was among the first communities in America to set aside a significant portion of its total land areas for open space—initially to secure a common public wood source. In 1693, Lynn restricted use of areas today encompassed by the Lynn Woods Reservation, and imposed fines for removing young trees. Although this land area was subsequently divided, in 1706, rights of public access were maintained, and, during the 19th century, recreational use of the woods increased.[114]

In 1850, the first hiking club in New England—the Lynn Exploring Circle—was established. In 1881, a group of Lynn residents organized the Trustees of the Free Public Forest to protect Lynn Woods by acquiring land and gifting it to the city.[115] Frederick Law Olmsted was hired as a design consultant for Lynn Woods, in 1889, whereupon he recommended keeping the land wild, adding only limited public access improvements.[114]

Lynn Woods was among the natural resources that inspired landscape architect Charles Eliot and others to create Boston's Metropolitan Park System. In 1893, Eliot noted that Lynn Woods "constitute the largest and most interesting, because the wildest, public domain in all New England."[114]

Today, Lynn has 49 parks encompassing 1,540 aggregate acres, representing about 22% of the city's total 6,874-acre land area. Consequently, 96% of all Lynn residents live within a 10-minute walk of a park or open space.[116][117] The city's parks and open spaces include:

- Lynn Shore Reservation

- Lynn Woods Reservation, the largest municipal park in New England, at 2,200 acres (8.9 km2). The bulk of the Reservation's land area is situated in the City of Lynn, but portions fall within the boundaries of adjoining municipalities. Several historical sites such as Stone Tower, Steel Tower, the Wolf Pits, and Dungeon Rock, believed to be the site of still-unrecovered pirate treasure, are located here. Many schools have cross-country track meets in Lynn Woods.

- Lynn Commons, an area between North and South Common Streets.

- Lynn Heritage State Park

- High Rock Tower, a stone observation tower with a view of Nahant, Boston, Downtown Lynn, Egg Rock, and the ocean. The top of the structure houses a telescope, which is open for the public to use.[118]

- Pine Grove Cemetery, an intact rural cemetery, and one of the largest cemeteries in the country. Ripley's Believe It or Not once claimed the fieldstone wall around the cemetery was the "second longest contiguous stone wall in the world", after the Great Wall of China.[119]

- Spring Pond, historic retreat of wild woodlands.

- Goldfish Pond/Lafayette Park

- Northern Strand Community Trail connects[120] Lynn with Revere, Saugus, Malden, and Everett, Massachusetts.[121]

Education

editLynn has three public high schools (Lynn English, Lynn Classical, and Lynn Vocational Technical High School), four middle/junior high schools, two alternative schools, and, as of Autumn 2015, 18 elementary schools.[122] They are served by the Lynn Public Schools district.

KIPP: the Knowledge Is Power Program operates the KIPP Academy Lynn, a 5–8 charter middle school, and a charter high school called KIPP Academy Lynn Collegiate.

There is also an independent Catholic high school located in the city, St. Mary's High School. There are two Catholic primary schools, St. Pius V School and Sacred Heart School. There is also one interdenominational Christian school, North Shore Christian School.[123]

North Shore Community College has a campus in downtown Lynn (with its other campuses located in Danvers and Beverly).

Infrastructure

editTransportation

editLynn has no Interstate or controlled-access highways, the nearest being U.S. Route 1 in Saugus and Lynnfield, and the combined Interstate 95 and Route 128 in Lynnfield. (The original design of Interstate 95 called for a route that would have paralleled Route 107 and crossed Lynn—including Lynn Woods—but the project was cancelled in 1972.[124][125]) However, Massachusetts State Route 1A, Route 107, Route 129 and Route 129A all pass through Lynn. Route 107 passes from southwest to northeast along a relatively straight right-of-way through the city. It shares a 0.5 miles (0.80 km) concurrency with Route 129A, which follows Route 129's old route through the city between its parent route and Route 1A. Route 129 passes from the north of the city before turning south and passing through the downtown area and becoming concurrent with Route 1A for 1 mile (1.6 km). Route 1A passes from Revere along the western portion of the Lynnway, a divided highway within the city, before passing further inland into Swampscott. The Lynnway itself runs along the coastline, leading to a rotary, which links the road to Nahant Road and Lynn Shore Drive, which follows the coast into Swampscott.

Lynn is served by Lynn station on the Newburyport/Rockport Line of the MBTA Commuter Rail system, as well as River Works station (which is for GE Aviation employees only). A number of other stations were open until the mid 20th century. Numerous MBTA bus routes also connect Lynn with Boston and the neighboring communities. An extension of the Blue Line to downtown Lynn has been proposed, but not funded. A ferry service to downtown Boston was operated in 2014, 2015, and 2017.[126][127] The nearest airport is Boston's Logan International Airport, about 5 miles (8.0 km) south.

Notable people

edit- Harry Agganis, All-American quarterback at Boston University and Boston Red Sox player

- Corinne Alphen, model and actress

- Stan Andrews, major league baseball player

- Julie Archoska, football player

- Paul Barresi, pornographic actor

- Louis P. Bénézet, educator and writer

- Verna Bloom, American actress (Animal House, High Plains Drifter, The Last Temptation of Christ)

- Ben Bowden, pitcher on 2014 Vanderbilt Commodores baseball team; currently pitches for the Atlanta Braves and has pitched for the Colorado Rockies

- Estelle Parsons, actress, singer and stage director, Best Supporting Actress 1967 Academy Awards, was born at Lynn in 1927.

- Walter Brennan, actor, winner of three Academy Awards, was born in Lynn

- Les Burke, major league baseball player

- Marion Cowan Burrows, physician and pharmacist, state legislator (1928–1932) representing Lynn

- John Deering, major league baseball player

- Joe Dixon, jazz clarinet player

- Frederick Douglass, abolitionist[32]

- Charles Remond Douglass, soldier

- Mary Baker Eddy, founder of Christian Science

- Zari Elmassian, singer, born in Lynn

- Derek Falvey, Major League Baseball executive, was raised in Lynn

- Josh Fogg, major league baseball player

- James Durrell Greene, famous inventor and US Civil War Brevet Brigadier General, was born in Lynn

- Bump Hadley, major league baseball player

- Neil Hamilton, actor, played "Commissioner Gordon" on TV's Batman

- George E. Harney, architect

- Jim Hegan, major league baseball player

- Frederick Herzberg, psychologist, most famous for introducing job enrichment and the Motivator-Hygiene theory, was born in Lynn

- Ken Hill, professional baseball player

- Mary Sargent Hopkins, women's health advocate and bicycle enthusiast

- Chris Howard, professional baseball pitcher

- Ruth Bancroft Law, aviator, was born in Lynn

- Jerry Maren, longtime character actor who played the middle "Lollipop Guild" member in 1939's "The Wizard Of Oz" film

- Jan Ernst Matzeliger, Surinamese inventor of shoe-manufacturing equipment, lived in Lynn

- Linda McCarriston, poet, was born and raised in Lynn

- Thomas M. McGee, attorney, State Representative, State Senator, Mayor of Lynn

- Thomas W. McGee, City Councillor, State Representative, Speaker of the Massachusetts House of Representatives

- Ralph McLane, clarinetist

- Walter Mears, journalist

- Ralph Merry, founder of Magog, Quebec, was born in Lynn in 1753.

- Mike Ness, musician, founder of the rock band, Social Distortion. Born in Lynn

- Alex Newell, actor and singer, notably from the hit TV series Glee

- Jack Noseworthy, actor

- Mike Pazik, major league baseball player

- William Dudley Pelley, founder of the Silver Legion of America

- Lotta S. Rand, social worker, Red Cross worker in WWI France

- Ruth Roman, actress, notably from Strangers on a Train, was born in Lynn

- Tom Rowe, professional hockey player

- Blondy Ryan, major league baseball player

- Harold Shapero, Composer and educator, was born in Lynn

- Todd Smith, pro wrestler

- Louise Spizizen, composer, musician, and author

- Susan Stafford, original hostess of Wheel of Fortune

- Lesley Stahl, television journalist, 60 Minutes, was born in Lynn

- Gasper Urban, football player

- Holman K. Wheeler, architect of more than 400 structures in Lynn[128]

- Frances Hodges White, children's author

- Tom Whelan, major league baseball player

- John Yau, poet and art critic

In popular culture

edit- Many versions of the Mother Goose nursery rhyme "Trot, trot to Boston" include Lynn as the second destination.[129]

- Scenes from the movie Surrogates (2009), especially the chase scene, were filmed in downtown Lynn.[130] Lynn native Jack Noseworthy starred in the film, and has said he pushes Lynn as a location whenever involved in a project.

- The character of Freddie Quell in The Master (2012) is from Lynn and returns there for a scene, though it was filmed in California.[131]

- The movie Black Mass (2015) starring Johnny Depp feature several scenes shot in Lynn.[132][133][134][135]

- The high school scene in Central Intelligence (2016) was filmed at Lynn Classical and Lynn English high schools.[136]

- Several scenes in Sound of Metal (2019) were filmed in Lynn.[137]

See also

edit- List of mill towns in Massachusetts

- Timeline of Lynn, Massachusetts

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Lynn, Massachusetts

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Essex County, Massachusetts

- List of museums in Massachusetts

- Lynn and Boston Railroad

- Lynn Belt Line Street Railway

- Boston, Revere Beach and Lynn Railroad

- Belden Bly Bridge

References

edit- ^ a b c "A BRIEF HISTORY OF LYNN". About Lynn. City of Lynn. Archived from the original on October 5, 2019. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

When the first official minister, Samuel Whiting, arrived from King's Lynn, England, the new settlers were so excited that they changed the name of their community to Lynn in 1637 in honor of him.

- ^ a b City of Lynn Massachusetts Semi-Centennial of Incorporation. Celebration Committee / Whitten & Cass, Printers. 1900. p. 63. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ a b c "Brief History of Lynn". www.cityoflynn.net. Archived from the original on July 7, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ City of Lynn Charter (PDF). Lynn, Massachusetts: City of Lynn. December 4, 2018. p. 1. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 11, 2022. Retrieved December 2, 2021.

The administration of the fiscal, prudential, and municipal affairs of the city, with the government thereof, shall be vested in an executive branch, to consist of the mayor, and a legislative branch, to consist of the city council.

- ^ "Welcome to the Mayor's Office". City of Lynn. Archived from the original on November 18, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ "The Lynn City Council 2020 - 2021". City of Lynn. Archived from the original on December 8, 2021. Retrieved December 1, 2021.

- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 21, 2022.

- ^ "Population and Housing Occupancy Status: 2010 - State -- County Subdivision, 2010 Census Redistricting Data (Public Law 94-171) Summary File". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved March 23, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ http://www.mapc.org/icc Archived June 24, 2016, at the Wayback Machine . Metropolitan Area Planning Commission. Retrieved on 2016-06-06.

- ^ "Massachusetts City and Town Incorporation and Settlement Dates". Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on June 6, 2009. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- ^ "Murals enliven downtown Lynn". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved May 10, 2018.

- ^ "Let's build Massachusetts by building the arts". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "IT'S HAPPENING HERE: Public art lifts the Lynn community". Gateways. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ a b "Group wants to cast Lynn in a whole new light". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ https://www.bostonglobe.com/metro/2012/08/08/lynn-sin-label-outdated-residents-insist/YhFRQtTGjftW7APTZsLdQL/story.html Archived June 1, 2016, at the Wayback Machine . Boston Globe. Retrieved on 2016-06-06.

- ^ "MACRIS inventory record for High Rock Reservation". Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on November 23, 2021. Retrieved November 22, 2021.

- ^ "Lynn Heritage State Park". Mass.gov. Archived from the original on May 15, 2018. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ^ http://www.essexheritage.org/aboutbyway Archived June 9, 2016, at the Wayback Machine . Essex National Heritage Area. Retrieved on 2016-06-07.

- ^ "Asset Detail". npgallery.nps.gov. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved May 13, 2018.

- ^ "Census - Geography Profile: Lynn city, Massachusetts". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 19, 2021. Retrieved September 18, 2021.

- ^ a b c d Perley, Sidney (1912). The Indian land titles of Essex County, Massachusetts. The Library of Congress. Salem, Mass. : Essex Book and Print Club.

- ^ https://archive.org/details/historyoflynn02lewi History of Lynn (1829). Retrieved on 2016-03-16

- ^ a b Brief History of Lynn Archived August 29, 2012, at the Wayback Machine at City of Lynn website

- ^ "Full text of "Thomas Halsey of Hertfordshire, England, and Southampton, Long Island, 1591-1679 : with his American descendants to the eighth and ninth generations"". archive.org. 1895. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ City of Lynn Archived July 23, 2001, at the Wayback Machine official website

- ^ USigs.org Archived March 23, 2004, at the Wayback Machine, History of Lynn Ch2-1814–1864 pub1890.

- ^ "Brief History of Lynn". www.cityoflynn.net. Archived from the original on October 20, 2016. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ^ Gifford, Jonathan (September 15, 2013). 100 Great Business Leaders: Of the world's most admired companies. Marshall Cavendish International Asia Pte Ltd. pp. 34–35. ISBN 9789814484688.

- ^ Amphilsoc.org Archived March 5, 2008, at the Wayback Machine, Elihu Thomson Papers at the American Philosophical Society

- ^ "G.E. Engineers Test Jet Engine". April 18, 2008. Archived from the original on December 11, 2021. Retrieved December 11, 2021.

- ^ "1860 Showmakers Strike in Lynn | Massachusetts AFL-CIO". Archived from the original on August 16, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ a b "Re-Examining Frederick Douglass's Time in Lynn". itemlive.org. February 2, 2018. Archived from the original on February 4, 2018. Retrieved February 3, 2018.

- ^ "The Life of Mary Baker Eddy". Marybakereddylibrary.org. December 3, 1910. Archived from the original on April 17, 2016. Retrieved June 5, 2016.

- ^ "Great Lynn Fire of 1889". www.celebrateboston.com. Archived from the original on May 21, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ "Lynn's Conflagration". Fall River Daily Evening News. November 27, 1889. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "The Jewish Heritage Center of the North Shore (Swampscott, Mass.)". jhcns.org. Archived from the original on June 19, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "Guide to the Congregation Anshai Sfard (Lynn, Massachusetts) Records, undated, 1899–2001 [Bulk 1952–2001], I-556". cjh.org. Archived from the original on September 18, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "Archdiocese of Boston Ethnic Parishes". bostoncatholic.org. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "Archdiocese of Boston Sacramental Record Inventory – Parishes by City, H-Z". bostoncatholic.org. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "St. George Greek Orthodox Church – Our Parish". stgeorgelynn.org. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ Vasquez, Daniel W. (January 2003). "Latinos in Lynn, Massachusetts". ScholarWorks at University of Massachusetts Boston. Archived from the original on August 19, 2016.

- ^ "Sanghikaram Wat Khmer – The Pluralism Project". pluralism.org. Retrieved July 3, 2016.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Jan Matzeliger". Biography. Archived from the original on December 12, 2019. Retrieved October 23, 2019.

- ^ "MACRIS Details". Massachusetts Historical Commission. Archived from the original on December 13, 2021. Retrieved December 13, 2021.

- ^ "Merrell Footlab". merrellfootlab.com. Archived from the original on June 18, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "How Lynn Became The Shoe Capitol of the World". wgbh.org. May 30, 2014. Archived from the original on August 28, 2016. Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ^ "Lynn Shore & Nahant Beach Reservation". Energy and Environmental Affairs. April 5, 2013. Archived from the original on July 4, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- ^ a b "Rent control was enacted in 1920". Mass Landlords, Inc. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ Gerstel, Steve (November 8, 1972). "Nixon Waltzes But Party Out Of Step". The Daily Item. Vol. 181, no. 128 Daily Evening Item. United Press International. pp. 1, 35. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ Taglakis, Tom (June 5, 1974). "Rent Control Scuttled 7-4". The Daily Item. Vol. 184, no. 222 Daily Evening Item. pp. 1, 12. Retrieved September 1, 2024.

- ^ 331 N.E.2d 529, 368 Mass. 311 (Mass. 1975).

- ^ Langer, Paul (November 29, 1981). "Day of the fire storm in Lynn". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on January 25, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ Yarin, Sophie (November 28, 2021). "40 Years Later: The Second Great Lynn Fire Revisited". Lynn Daily Item. Archived from the original on October 1, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

Today, North Shore Community College stands where a massive portion of the fire's damage was done.

- ^ Méras, Phyllis (2007). The Historic Shops & Restaurants of Boston. p. 56.

- ^ Kerry, John (November 27, 2007). "Don't Leave New England Families Out in the Cold". United States Senate. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e "A BRIEF HISTORY OF LYNN". About Lynn. City of Lynn. Archived from the original on October 5, 2019. Retrieved October 19, 2019.

The first Electric Trolley in the state ran from Lynn in 1888

- ^ "Famous Firsts in Massachusetts". History of Massachusetts. Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

1888 The first electric trolley in the state runs in Lynn.

- ^ The Thomson-Houston Road at Lynn, Mass. Archived February 15, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, The Electrical World, December 8, 1888, page 303

- ^ Electric Railway at Lynn, Mass. Archived February 15, 2023, at the Wayback Machine, Electric Power, January 1889, page 21

- ^ "Famous Firsts in Massachusetts". History of Massachusetts. Secretary of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on July 28, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2019.

1629 The first tannery in the U.S. began operations in Lynn.

- ^ Daley, Beth (March 6, 1997). "Rhyme may be reason to change Lynn's name". Boston Globe. Retrieved January 13, 2010.

- ^ Leyes, Richard A. (1999). The history of North American small gas turbine aircraft engines. William A. Fleming, National Air and Space Museum. Reston, Va.: AIAA. p. 238. ISBN 1-56347-332-1. OCLC 42296510.

- ^ "Behind the Marshmallow Curtain: A Look Inside Lynn's Marshmallow Fluff Factory". Boston Magazine. September 24, 2014. Archived from the original on January 27, 2022. Retrieved April 26, 2022.

- ^ "Lynn's sin label outdated, residents insist". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved June 12, 2016.

- ^ a b "Murals enliven downtown Lynn". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "DOWNTOWN LYNN CULTURAL DISTRICT | you won't go out the way you came in". dtlcd.org. Archived from the original on February 12, 2015. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ "Mass Cultural Council | Services | Cultural Districts". www.massculturalcouncil.org. Archived from the original on June 16, 2016. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ^ "Governor launches task force to revive Lynn's fortunes". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ^ "Work to resume on Lynn lofts | Itemlive". www.itemlive.com. Archived from the original on June 29, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ^ "Flip This House – Lynn House is Being Renovated for A&E Network Series | Lynn Journal". Archived from the original on April 6, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ^ "Lynn is at the Center of Development, North of Boston | Lynn Journal". Archived from the original on June 25, 2016. Retrieved June 9, 2016.

- ^ "Developers Have Discovered Lynn. What Comes Next?". www.wbur.org. October 11, 2019. Archived from the original on December 13, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ "Monday marked the groundbreaking of the luxury apartment development on Munroe Street". Itemlive. November 6, 2018. Archived from the original on December 13, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ "Lynn breaks ground on $100M waterfront development". Itemlive. December 12, 2019. Archived from the original on December 13, 2019. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ "Transit Oriented Development Comes To Lynn". News. June 1, 2018. Archived from the original on December 15, 2019. Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- ^ "Beyond Walls meant business - Itemlive". Itemlive. July 24, 2017. Archived from the original on April 2, 2018. Retrieved April 1, 2018.

- ^ "The Lights Will Stay On At Lynn's High Rock Tower Thanks To A Crowdfunding Campaign". Lynn Item. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ "Beyond Walls Lights Up Downtown Lynn 'Like Times Square On New Year's Eve'". Lynn Item. Archived from the original on August 15, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2018.

- ^ "What You Need To Know Before Lynn's 'Rock The Block' Celebration - Itemlive". Itemlive. July 21, 2017. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ "Strong Response To Ironbound's Food Truck Emporium In Lynn - Itemlive". Itemlive. April 22, 2018. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

- ^ Rosenberg, Steven A. (January 17, 2013). "Gay meccas in Mass". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on August 6, 2016. Retrieved June 18, 2016.

- ^ "Best places to live in Massachusetts". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on May 18, 2018. Retrieved May 18, 2018.

- ^ Kuzub, Alena (August 18, 2021). "Frederick Douglass Park Dedicated". Lynn Daily Item. Archived from the original on August 20, 2021. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ "An Act designating a certain park in the city of Lynn as the Frederick Douglass Park". The General Court of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts. Archived from the original on July 28, 2021. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ^ "210916 Launch of Vision Lynn" (PDF) (Press release). City of Lynn. September 21, 2016. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Public Comment Period: Opportunities to Engage". Lynn In Common. Retrieved April 25, 2023.

- ^ "Global Protection Corp". Greater Lynn Chamber of Commerce. Retrieved July 22, 2024.

- ^ "Lynnway Park". www.lynnwaypark.com. Retrieved June 14, 2024.

- ^ "PRISM Climate Group at Oregon State University". Northwest Alliance for Computational Science & Engineering (NACSE), based at Oregon State University. Retrieved March 16, 2023.

- ^ "Total Population (P1), 2010 Census Summary File 1". American FactFinder, All County Subdivisions within Massachusetts. United States Census Bureau. 2010.

- ^ "Massachusetts by Place and County Subdivision - GCT-T1. Population Estimates". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1990 Census of Population, General Population Characteristics: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1990. Table 76: General Characteristics of Persons, Households, and Families: 1990. 1990 CP-1-23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1980 Census of the Population, Number of Inhabitants: Massachusetts" (PDF). US Census Bureau. December 1981. Table 4. Populations of County Subdivisions: 1960 to 1980. PC80-1-A23. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1950 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. 1952. Section 6, Pages 21-10 and 21-11, Massachusetts Table 6. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1930 to 1950. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1920 Census of Population" (PDF). Bureau of the Census. Number of Inhabitants, by Counties and Minor Civil Divisions. Pages 21-5 through 21-7. Massachusetts Table 2. Population of Counties by Minor Civil Divisions: 1920, 1910, and 1920. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1890 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. Pages 179 through 182. Massachusetts Table 5. Population of States and Territories by Minor Civil Divisions: 1880 and 1890. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1870 Census of the Population" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1872. Pages 217 through 220. Table IX. Population of Minor Civil Divisions, &c. Massachusetts. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1860 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1864. Pages 220 through 226. State of Massachusetts Table No. 3. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "1850 Census" (PDF). Department of the Interior, Census Office. 1854. Pages 338 through 393. Populations of Cities, Towns, &c. Retrieved July 12, 2011.

- ^ "Number of Inhabitants" (PDF). 1950 Census of Population. 1. Bureau of the Census. Section 6, Pages 21–7 through 21-09, Massachusetts Table 4. Population of Urban Places of 10,000 or more from Earliest Census to 1920. 1952. Archived (PDF) from the original on October 10, 2022. Retrieved January 18, 2023.

- ^ "City and Town Population Totals: 2020-2022". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved November 11, 2023.

- ^ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on July 1, 2021. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ^ "P004 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2000: DEC Summary File 1 – Lynn city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2010: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Lynn city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ "P2 Hispanic or Latino, and Not Hispanic or Latino by Race – 2020: DEC Redistricting Data (PL 94-171) – Lynn city, Massachusetts". United States Census Bureau.

- ^ a b c "Profile of General Population and Housing Characteristics Lynn, MA: 2010". American FactFinder – United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020.

- ^ "Lynn (city), Massachusetts Quick Facts". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on April 3, 2013.

- ^ a b Buote, Brenda J, "Asian population up in small cities" (Archive). Boston Globe. June 13, 2004. Retrieved on September 10, 2015.

- ^ "SELECTED ECONOMIC CHARACTERISTICS 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 17, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ "ACS DEMOGRAPHIC AND HOUSING ESTIMATES 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on January 5, 2015. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ "HOUSEHOLDS AND FAMILIES 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates". U.S. Census Bureau. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved January 12, 2015.

- ^ "Massachusetts Representative Districts". Sec.state.ma.us. Archived from the original on May 20, 2022. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- ^ "Election Results".

- ^ a b c "Lynn Woods Historic District--MA Conservation: A Discover Our Shared Heritage Travel Itinerary". www.nps.gov. Archived from the original on November 3, 2018. Retrieved November 3, 2018.

- ^ Annual Report of the Park Commissioners of the City of Lynn ... The Commissioners. 1890. Archived from the original on February 15, 2023. Retrieved October 18, 2020.

- ^ "ParkServe". ParkServe. The Trust for Public Land. Archived from the original on November 10, 2017. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ "U.S. Census Bureau Quick Facts". U.S. Census Bureau Quick Facts. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved November 9, 2017.

- ^ "High Rock Park, Tower and Observatory". Official Website. Archived from the original on October 4, 2008. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ "Pine Grove Cemetery". Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved January 17, 2023.

- ^ "Ribbon Cutting for Lynn Section of Northern Strand Path". November 20, 2021. Archived from the original on December 10, 2021. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

On Friday, November 19th, ... a ribbon cutting to officially open the newly completed paving and improvements on the Northern Strand in Lynn.

- ^ "Learn about the Community Path of Lynn". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on May 24, 2018. Retrieved December 10, 2021.

- ^ Lynn Public Schools. "School Profiles". Archived from the original on August 11, 2007. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- ^ Massachusetts Department of Education. "Lynn – Directory Information". Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved August 2, 2007.

- ^ "The Roads Not Taken". www.architects.org. Archived from the original on August 19, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ "Interstate 95-Massachusetts (North of Boston Section)". www.bostonroads.com. Archived from the original on April 30, 2017. Retrieved June 14, 2017.

- ^ Rosenberg, Steven A. (June 5, 2014). "Lynn hopes ferry boosts waterfront". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on August 8, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ^ "Baker Says No to Ferry". Lynn Daily Item. May 10, 2018. Archived from the original on May 13, 2018. Retrieved May 12, 2018.

- ^ Industries of Massachusetts: Historical and Descriptive Review of Lynn, Lowell, Lawrence, Haverhill, Salem, Beverly, Peabody, Danvers, Gloucester, Newburyport, and Amesbury, and their leading Manufacturers and Merchants. International Publishing Co. 1886. p. 52. Retrieved September 22, 2019.

- ^ Ra, Carol F. (1987). Trot, trot, to Boston: play rhymes for baby. New York: Lothrop, Lee & Shepard Books. ISBN 0688061907.. "Trot, trot, to Boston; Trot, trot, to Lynn; Trot, trot, to Salem; Home, home again."

- ^ LynnCAM TV (October 28, 2008). Hollywood Meets Lynn: The Surrogates. Lynn, Massachusetts: LynnCAM TV. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ^ Mukhopadhyay, Arka (April 13, 2021). "Where Was The Master Filmed?". The Cinemaholic. Retrieved March 21, 2024.

- ^ "The movie Black Mass is recreating the St. Patrick's Day Parade in downtown Lynn, MA on Monday, June 23". June 19, 2014. Archived from the original on June 6, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ "'Black Mass' Filming at The Porthole Pub in Lynn". June 3, 2014. Archived from the original on October 27, 2017. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ "'Black Mass', starring Johnny Depp, filming in Lynn, MA on Monday". July 18, 2014. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ "'Black Mass' takes its sets to Lynn and back to the '70s and '80s". The Boston Globe. Archived from the original on April 24, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- ^ "Lynn High Schools Are Central To Movie". Daily Item. Lynn, MA. June 17, 2016. Archived from the original on December 1, 2017. Retrieved November 18, 2017.

- ^ "Sound of Metal (2019) - Filming & production", IMDb, retrieved March 21, 2024

Bibliography

edit- Lewis, Alonzo and James Robinson Newhall. History of Lynn, Essex County, Massachusetts: Including Lynnfield, Saugus, Swampscott and Nahant. Published 1865 by John L. Shorey 13 Washington St. Lynn.

- Panoramic View of the Hutchinson Family Home on High Rock including all of Lynn, Massachusetts published 1881 by Armstrong and Co, at the LOC website.

- D'Entremont, Jeremy. Egg Rock Lighthouse History. Website.

- Carlson, W. Bernard. Innovation as a Social Process: Elihu Thomson and the Rise of General Electric, 1870–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

- Woodbury, David O. Elihu Thomson, Beloved Scientist (Boston: Museum of Science, 1944)

- Haney, John L. The Elihu Thomson Collection, American Philosophical Society Yearbook 1944.

- United Press International. "Blaze destroys urban complex in Lynn, Mass." The New York Times, November 29, 1981. Page 28.