Pregabalin, sold under the brand name Lyrica among others, is an anticonvulsant, analgesic, and anxiolytic amino acid medication used to treat epilepsy, neuropathic pain, fibromyalgia, restless legs syndrome, opioid withdrawal, and generalized anxiety disorder (GAD).[13][17][18] Pregabalin also has antiallodynic properties.[19][20][21] Its use in epilepsy is as an add-on therapy for partial seizures.[13] It is a gabapentinoid medication (GABA analogue) which are drugs that are derivatives of γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter.[22][23][24][25] Pregabalin acts by inhibiting certain calcium channels.[13][26][27] When used before surgery, it reduces pain but results in greater sedation and visual disturbances.[28] It is taken by mouth.[13]

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /priˈɡæbəlɪn/ |

| Trade names | Lyrica, others[1] |

| Other names | 3-Isobutyl-GABA; (S)-3-Isobutyl-γ-aminobutyric acid; Isobutylgaba; CI-1008; PD-144723 |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a605045 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Dependence liability | Physical: High[4] Psychological: Moderate[4] |

| Addiction liability | Low[4] (but varying with dosage and route of administration) |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Oral: ≥90%[11] |

| Protein binding | <1%[12] |

| Metabolites | N-methylpregabalin[11] |

| Onset of action | May occur within a week (pain)[13] |

| Elimination half-life | 4.5–7 hours[14] (mean 6.3 hours)[14][15] |

| Duration of action | 8–12 hours [16] |

| Excretion | Kidney |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.119.513 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C8H17NO2 |

| Molar mass | 159.229 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Common side effects include headache, dizziness, sleepiness, confusion, trouble with memory, poor coordination, dry mouth, problems with vision, and weight gain.[13][29] Serious side effects may include angioedema, drug misuse, and an increased suicide risk.[13] When pregabalin is taken at high doses over a long period of time, addiction may occur, but if taken at usual doses the risk is low.[4] Use during pregnancy or breastfeeding is of unclear safety.[30]

Pregabalin was approved for medical use in the United States in 2004.[13] It was developed as a successor to the related gabapentin.[31] It is available as a generic medication.[29][32][33][34][35] In 2022, it was the 91st most commonly prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 7 million prescriptions.[36][37] In the US, pregabalin is a Schedule V controlled substance under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970,[13] which means that the drug has low abuse potential compared to substances in Schedules I-IV, however, there is still a potential for misuse.[38] Despite the low abuse potential, there have been reports of euphoria, improved happiness, excitement, calmness, and a "high" similar to marijuana with the use of pregabalin; there is a potential for developing dependence on these substances, and withdrawal symptoms may occur if the medication is abruptly discontinued.[39][40] It is a Class C controlled substance in the UK.[41] Therefore, pregabalin requires a prescription.[42][43] Furthermore, the prescription must clearly set forth the dose.[44] Pregabalin has potential for misuse. It can bring about an elevated mood in users. It can also have serious side effects, particularly when used in combination with other drugs.[44][45]

Medical uses

editSeizures

editFor drug-resistant focal epilepsy, pregabalin is useful as an add-on therapy to other treatments.[46] Its use alone is less effective than some other seizure medications.[47] It is unclear how it compares to gabapentin for this use.[47]

Neuropathic pain

editThe European Federation of Neurological Societies recommends pregabalin as a first line agent for the treatment of pain associated with diabetic neuropathy, post-herpetic neuralgia, and central neuropathic pain.[48] A minority obtain substantial benefit, and a larger number obtain moderate benefit.[49] It is given equal weight as gabapentin and tricyclic antidepressants as a first-line agent, however the latter are less expensive as of 2010.[50] Pregabalin is as effective at relieving pain as duloxetine and amitriptyline. Combination treatment of pregabalin and amitriptyline or duloxetine offers additional pain relief for people whose pain is not adequately controlled with one medication, and is safe.[51][52]

Studies have shown that higher doses of pregabalin are associated with greater efficacy.[53]

Pregabalin's use in cancer-associated neuropathic pain is controversial,[54] though such use is common.[55] It has been examined for the prevention of post-surgical chronic pain, but its utility for this purpose is controversial.[56][57]

Pregabalin is generally not regarded as efficacious in the treatment of acute pain.[49] In trials examining the utility of pregabalin for the treatment of acute post-surgical pain, no effect on overall pain levels was observed, but people did require less morphine and had fewer opioid-related side effects.[56][58] Several possible mechanisms for pain improvement have been discussed.[59]

Anxiety disorders

editPregabalin is effective for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder.[60] It is also effective for the short- and long-term treatment of social anxiety disorder and in reducing preoperative anxiety.[61][62] However, there is concern regarding pregabalin's off-label use due to the lack of strong scientific evidence for its efficacy in multiple conditions and its proven side effects.[63]

The World Federation of Biological Psychiatry recommends pregabalin as one of several first line agents for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder, but recommends other agents such as those of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) class as first line treatment for obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD) and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[64][65] For PTSD, pregabalin as complementary treatment seems to be effective.[62]

Generalized anxiety disorder

editPregabalin has anxiolytic effects similar to benzodiazepines with less risk of dependence.[66] The effects of pregabalin appear within one week of use,[67] and are similar in effectiveness to lorazepam, alprazolam, and venlafaxine, but pregabalin has demonstrated superiority by producing more consistent therapeutic effects for psychosomatic anxiety symptoms.[68] Long-term trials have shown continued effectiveness without the development of tolerance, and, in addition, unlike benzodiazepines, it has a beneficial effect on sleep and sleep architecture, characterized by the enhancement of slow-wave sleep.[68] It produces less severe cognitive and psychomotor impairment compared to benzodiazepines.[68][66]

A 2019 review found that pregabalin reduces symptoms, and was generally well tolerated.[60]

Other uses

editAlthough pregabalin is sometimes prescribed for people with bipolar disorder, there is no evidence showing that it is effective.[62][69]

There is no evidence and significant risk in using pregabalin for sciatica and low back pain.[70][71][72] Evidence of benefit in alcohol withdrawal as well as withdrawal from certain other drugs is limited as of 2016.[73]

There is no evidence for its use in the prevention of migraines and gabapentin has also been found not to be useful.[74]

Adverse effects

editExposure to pregabalin is associated with weight gain, drowsiness, fatigue, dizziness, vertigo, leg swelling, disturbed vision, loss of coordination, and euphoria.[75] It has an adverse effect profile similar to other central nervous system (CNS) depressants.[76] Even though pregabalin is a depressant and anticonvulsant, it can sometimes paradoxically induce seizures, particularly in large overdoses.[77] Adverse drug reactions associated with the use of pregabalin include:[78][79]

- Very common (>10% of people with pregabalin): dizziness, drowsiness.

- Common (1–10% of people with pregabalin): blurred vision, diplopia, increased appetite and subsequent weight gain, euphoria, confusion, vivid dreams, changes in libido (increase or decrease), irritability, ataxia, attention changes, feeling high, memory impairment, tremor, dysarthria, paresthesia, vertigo, dry mouth, constipation, nausea, vomiting, flatulence, erectile dysfunction, fatigue, peripheral edema, feelings of drunkenness, abnormal walking, asthenia, nasopharyngitis, increased creatine kinase level.

- Infrequent (0.1–1% of people with pregabalin): depression, lethargy, agitation, anorgasmia, hallucinations, myoclonus, hypoaesthesia, hyperaesthesia, tachycardia, hypersalivation, hypoglycaemia, excessive sweating, flushing, rash, muscle cramp, myalgia, arthralgia, urinary incontinence, dysuria, thrombocytopenia, kidney calculus.

- Rare (<0.1% of people with pregabalin): neutropenia, first-degree heart block, hypotension, hypertension, pancreatitis, dysphagia, oliguria, rhabdomyolysis, suicidal thoughts or behavior.[80]

Cases of recreational use, with associated adverse effects have been reported.[81]

Withdrawal symptoms

editFollowing abrupt or rapid discontinuation of pregabalin, some people reported symptoms suggestive of physical dependence. The FDA determined that the substance dependence profile of pregabalin, as measured by a personal physical withdrawal checklist, was quantitatively less than benzodiazepines.[76] Even people who have discontinued short term use of pregabalin have experienced withdrawal symptoms including insomnia, headache, nausea, anxiety, diarrhea, flu-like symptoms, major depression, pain, seizures, excessive sweating, and dizziness.[82]

Pregnancy

editIt is unclear if it is safe for use in pregnancy with some studies showing potential harm.[83]

Breathing

editIn December 2019, the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned about serious breathing issues for those taking gabapentin or pregabalin when used with central nervous system (CNS) depressants or for those with lung problems.[84][85]

The FDA required new warnings about the risk of respiratory depression to be added to the prescribing information of the gabapentinoids.[84] The FDA also required the drug manufacturers to conduct clinical trials to further evaluate their abuse potential, particularly in combination with opioids, because misuse and abuse of these products together is increasing, and co-use may increase the risk of respiratory depression.[84]

Among 49 case reports submitted to the FDA over the five-year period from 2012 to 2017, twelve people died from respiratory depression with gabapentinoids, all of whom had at least one risk factor.[84]

The FDA reviewed the results of two randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials in healthy people, three observational studies, and several studies in animals.[84] One trial showed that using pregabalin alone and using it with an opioid pain reliever can depress breathing function.[84] The other trial showed gabapentin alone increased pauses in breathing during sleep.[84] The three observational studies at one academic medical center showed a relationship between gabapentinoids given before surgery and respiratory depression occurring after different kinds of surgeries.[84] The FDA also reviewed several animal studies that showed pregabalin alone and pregabalin plus opioids can depress respiratory function.[84]

Overdose

editAn overdose of pregabalin usually consists of severe drowsiness, severe ataxia, blurred vision, macular detachment,[86] slurred speech, severe uncontrollable jerking motions (myoclonus), tonic–clonic seizures, and anxiety.[87] Despite these symptoms an overdose is not usually fatal unless mixed with another CNS depressant. Several people with kidney failure developed myoclonus while receiving pregabalin, apparently as a result of gradual accumulation of the drug. Acute overdosage may be manifested by drowsiness, tachycardia, and hypertonia. Plasma, serum, or blood concentrations of pregabalin may be measured to monitor therapy or to confirm a diagnosis of poisoning in hospitalized people.[88][89][90]

Interactions

editNo interactions have been demonstrated in vivo. The manufacturer notes some potential pharmacological interactions with opioids, benzodiazepines, barbiturates, ethanol (alcohol), and other drugs that depress the central nervous system. ACE inhibitors may enhance the adverse/toxic effect of pregabalin. Pregabalin may enhance the fluid-retaining effect of certain anti-diabetic agents (thiazolidinediones).[91]

Pharmacology

editMechanism of action

editPregabalin is a gabapentinoid medication, which are drugs that are derivatives of the γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA), an inhibitory neurotransmitter.[22][23][24][25]

Pregabalin inhibits certain calcium channels, namely, it blocks α2δ subunit-containing voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs).[13][26]

While the exact mechanism of action of pregabalin is not definitively characterized, is believed that the main action is exhibited specifically by its binding to the α2δ subunit of VDCCs, so that this binding modulates calcium influx at the nerve terminals, thereby inhibiting the release of excitatory neurotransmitters. These excitatory neurotransmitters include glutamate, norepinephrine (noradrenaline), serotonin, dopamine, substance P, and calcitonin gene-related peptide. By inhibiting the release of these neurotransmitters, pregabalin can reduce the transmission of pain signals, which helps alleviate symptoms and provides relief for patients experiencing pain, seizures, or other related symptoms.[92]

Whereas pregabalin is structurally similar to GABA, pregabalin it does not bind directly to GABA receptors, which supports the notion that its therapeutic effects are achieved through its action on the α2δ subunit of VDCCs.[92]

Pharmacodynamics

editPregabalin is a gabapentinoid and acts by inhibiting certain calcium channels.[26][27] Specifically it is a ligand of the auxiliary α2δ subunit site of certain voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs), and thereby acts as an inhibitor of α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs.[26][93] There are two drug-binding α2δ subunits, α2δ-1 and α2δ-2, and pregabalin shows similar affinity for (and hence lack of selectivity between) these two sites.[26] Pregabalin is selective in its binding to the α2δ VDCC subunit.[93][25] Despite the fact that pregabalin is a GABA analogue,[94] it does not bind to the GABA receptors, does not convert into GABA or another GABA receptor agonist in vivo, and does not directly modulate GABA transport or metabolism.[27][93] However, pregabalin has been found to produce a dose-dependent increase in the brain expression of L-glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD), the enzyme responsible for synthesizing GABA, and hence may have some indirect GABAergic effects by increasing GABA levels in the brain.[95][96][97] There is currently no evidence that the effects of pregabalin are mediated by any mechanism other than inhibition of α2δ-containing VDCCs.[93][98] In accordance, inhibition of α2δ-1-containing VDCCs by pregabalin appears to be responsible for its anticonvulsant, analgesic, and anxiolytic effects.[93][98]

The endogenous α-amino acids L-leucine and L-isoleucine, which closely resemble pregabalin and the other gabapentinoids in chemical structure, are apparent ligands of the α2δ VDCC subunit with similar affinity as the gabapentinoids (e.g., IC50=71 nM for L-isoleucine), and are present in human cerebrospinal fluid at micromolar concentrations (e.g., 12.9 μM for L-leucine, 4.8 μM for L-isoleucine).[23] It has been theorized that they may be the endogenous ligands of the subunit and that they may competitively antagonize the effects of gabapentinoids.[23][99] In accordance, while gabapentinoids like pregabalin and gabapentin have nanomolar affinities for the α2δ subunit, their potencies in vivo are in the low micromolar range, and competition for binding by endogenous L-amino acids has been said to likely be responsible for this discrepancy.[98]

Pregabalin was found to possess 6-fold higher affinity than gabapentin for α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs in one study.[100][101] However, another study found that pregabalin and gabapentin had similar affinities for the human recombinant α2δ-1 subunit (Ki=32 nM and 40 nM, respectively).[102] In any case, pregabalin is 2 to 4 times more potent than gabapentin as an analgesic[94][103] and, in animals, appears to be 3 to 10 times more potent than gabapentin as an anticonvulsant.[94][103]

Pharmacokinetics

editAbsorption

editPregabalin is absorbed from the intestines by an active transport process mediated via the large neutral amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1, SLC7A5), a transporter for amino acids such as L-leucine and L-phenylalanine.[26][93][104] Very few (less than 10 drugs) are known to be transported by this transporter.[105] Unlike gabapentin, which is transported solely by the LAT1,[104][12] pregabalin seems to be transported not only by the LAT1 but also by other carriers.[26] The LAT1 is easily saturable, so the pharmacokinetics of gabapentin are dose-dependent, with diminished bioavailability and delayed peak levels at higher doses.[26] In contrast, this is not the case for pregabalin, which shows linear pharmacokinetics and no saturation of absorption.[26]

The oral bioavailability of pregabalin is greater than or equal to 90% across and beyond its entire clinical dose range (75 to 600 mg/day).[12] Food does not significantly influence the oral bioavailability of pregabalin.[12] Pregabalin is rapidly absorbed when administered on an empty stomach, with a Tmax (time to peak levels) of generally less than or equal to 1 hour at doses of 300 mg or less.[26][11] However, food has been found to substantially delay the absorption of pregabalin and to significantly reduce peak levels without affecting the bioavailability of the drug; Tmax values for pregabalin of 0.6 hours in a fasted state and 3.2 hours in a fed state (5-fold difference), and the Cmax is reduced by 25–31% in a fed versus fasted state.[12]

Distribution

editPregabalin crosses the blood–brain barrier and enters the central nervous system.[93] However, due to its low lipophilicity,[12] pregabalin requires active transport across the blood–brain barrier.[104][93][106][107] The LAT1 is highly expressed at the blood–brain barrier[108] and transports pregabalin across into the brain.[104][93][106][107] Pregabalin has been shown to cross the placenta in rats and is present in the milk of lactating rats.[11] In humans, the volume of distribution of an orally administered dose of pregabalin is approximately 0.56 L/kg.[11] Pregabalin is not significantly bound to plasma proteins (<1%).[12]

Metabolism

editPregabalin undergoes little or no metabolism.[12][26][109] In experiments using nuclear medicine techniques, it was revealed that approximately 98% of the radioactivity recovered in the urine was unchanged pregabalin.[11] The main metabolite is N-methylpregabalin.[11]

Pregabalin is generally safe in patients with liver cirrhosis.[110]

Elimination

editPregabalin is eliminated by the kidneys in the urine, mainly in its unchanged form.[12][11] It has a relatively short elimination half-life, with a reported value of 6.3 hours.[12] Because of its short elimination half-life, pregabalin is administered 2 to 3 times per day to maintain therapeutic levels.[12] The kidney clearance of pregabalin is 73 mL/minute.[9]

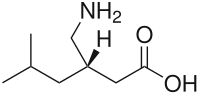

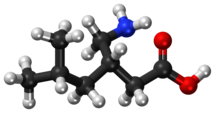

Chemistry

editPregabalin is a GABA analogue that is a 3-substituted derivative as well as a γ-amino acid.[19][25] Specifically, pregabalin is (S)-(+)-3-isobutyl-GABA.[111][112][113] Pregabalin also closely resembles the α-amino acids L-leucine and L-isoleucine, and this may be of greater relevance in relation to its pharmacodynamics than its structural similarity to GABA.[23][99][111]

Synthesis

editChemical syntheses of pregabalin have been described.[114][115]

History

edit| External videos | |

|---|---|

| "Richard B. Silverman, Basic Science to Blockbuster Drug", National Academy of Inventors |

Pregabalin was synthesized in 1990 as an anticonvulsant. It was invented by medicinal chemist Richard Bruce Silverman at Northwestern University in Evanston, Illinois.[116] Silverman is best known for identifying the drug pregabalin as a possible treatment for epileptic seizures.[117] During 1988 to 1990, Ryszard Andruszkiewicz, a visiting research fellow, synthesized a series of molecules requested by Silverman.[118] One looked particularly promising.[119] The molecule was effectively shaped for transportation into the brain, where it activated L-glutamic acid decarboxylase, an enzyme. Silverman hoped that the enzyme would increase production of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA and block convulsions.[117] Eventually, the set of molecules were sent to Parke-Davis Pharmaceuticals for testing. The drug was approved in the European Union in 2004. The US received FDA approval for use in treating epilepsy, diabetic neuropathic pain, and postherpetic neuralgia in December 2004. Pregabalin then appeared on the US market under the brand name Lyrica in fall of 2005.[120] In 2017, the FDA approved pregabalin extended-release Lyrica CR for the management of neuropathic pain associated with diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and postherpetic neuralgia.[121] However, unlike the immediate release formulation, Lyrica CR was not approved for the management of fibromyalgia or as add-on therapy for adults with partial onset seizures.[122][9]

Society and culture

editLegal status

edit- United States: During clinical trials a small number of users (~4%) reported euphoria after use, which led to its control in the US.[123] The Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) classified pregabalin as a depressant and placed pregabalin, including its salts, and all products containing pregabalin into Schedule V of the Controlled Substances Act.[124][76][125]

- Norway: Pregabalin is in prescription Schedule B, alongside benzodiazepines.[126][127]

- United Kingdom: On January 14, 2016, the Advisory Council on the Misuse of Drugs (ACMD) wrote a letter to Home Office ministers recommending that pregabalin alongside gabapentin should be controlled under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971.[128][129] It was announced in October 2018, that Pregabalin would become reclassified as a class C controlled substance from April 2019.[130][41][131]

In the United States, the FDA has approved pregabalin for adjunctive therapy for adults with partial onset seizures, management of postherpetic neuralgia and neuropathic pain associated with spinal cord injury and diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and the treatment of fibromyalgia.[132] Pregabalin has also been approved in the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Russia for treatment of generalized anxiety disorder.[133][68][134]

Economics

editPregabalin is available as a generic medication in a number of countries, including the United States as of July 2019.[29][32][133] In the United States as of July 2019 the wholesale/pharmacy cost for generic pregabalin is US$0.17–0.22 per 150 mg capsule.[135]

Since 2008, Pfizer has engaged in extensive direct-to-consumer advertising campaigns to promote its branded product Lyrica for fibromyalgia and diabetic nerve pain indications. In January 2016, the company spent a record amount, $24.6 million for a single drug on TV ads, reaching global revenues of $14 billion, more than half in the United States.[136]

Up until 2009, Pfizer promoted Lyrica for other uses which had not been approved by medical regulators. For Lyrica and three other drugs, Pfizer was fined a record amount of US$2.3 billion by the Department of Justice,[137][138][139] after pleading guilty to advertising and branding "with the intent to defraud or mislead". Pfizer illegally promoted the drugs, with doctors "invited to consultant meetings, many in resort locations; attendees expenses were paid; they received a fee just for being there", according to prosecutor Michael Loucks.[137][138]

Intellectual property

editProfessor Richard "Rick" Silverman of Northwestern University developed pregabalin there. The university holds a patent on it, exclusively licensed to Pfizer.[140][141] That patent, along with others, was challenged by generic manufacturers and was upheld in 2014, giving Pfizer exclusivity for Lyrica in the US until 2018.[142][143]

Pfizer's main patent for Lyrica, for seizure disorders, in the UK expired in 2013. In November 2018, the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom ruled that Pfizer's second patent on the drug, for treatment of pain, was invalid because there was a lack of evidence for the conditions it covered – central and peripheral neuropathic pain. From October 2015, GPs were forced to change people from generic pregabalin to branded until the second patent ran out in July 2017. This cost the NHS £502 million.[144]

Brand names

editAs of October 2017, pregabalin is marketed under many brand names: Algerika, Alivax, Alyse, Alzain, Andogablin, Aprion, Averopreg, Axual, Balifibro, Brieka, Clasica, Convugabalin, Dapapalin, Dismedox, Dolgenal, Dolica, Dragonor, Ecubalin, Epica, Epiron, Gaba-P, Gabanext, Gabarol, Gabica, Gablin, Gablovac, Gabrika, Gavin, Gialtyn, Glonervya, Helimon, Hexgabalin, Irenypathic, Kabian, Kemirica, Kineptia, Lecaent, Lingabat, Linprel, Lyribastad, Lyric, Lyrica, Lyrineur, Lyrolin, Lyzalon, Martesia, Maxgalin, Mystika, Neuragabalin, Neugaba, Neurega, Neurica, Neuristan, Neurolin, Neurovan, Neurum, Newrica, Nuramed, Paden, Pagadin, Pagamax, Painica, Pevesca, PG, Plenica, Pragiola, Prebalin, Prebanal, Prebel, Prebictal, Prebien, Prefaxil, Pregaba, Pregabalin, Pregabalina, Pregabaline, Prégabaline, Pregabalinum, Pregabateg, Pregaben, Pregabid, Pregabin, Pregacent, Pregadel, Pregagamma, Pregalex, Pregalin, Pregalodos, Pregamid, Pregan, Preganerve, Pregastar, Pregatrend, Pregavalex, Pregdin Apex, Pregeb, Pregobin, Prejunate, Prelin, Preludyo, Prelyx, Premilin, Preneurolin, Prestat, Pretor, Priga, Provelyn, Regapen, Resenz, Rewisca, Serigabtin, Symra, Vronogabic, Xablin, and Xil.[145]

It is marketed as a combination drug with mecobalamin under the brand names Agemax-P, Alphamix-PG, Freenerve-P, Gaben, Macraberin-P, Mecoblend-P, Mecozen-PG, Meex-PG, Methylnuron-P, Nervolin, Nervopreg, Neurica-M, Neuroprime-PG, Neutron-OD, Nuroday-P, Nurodon-PG, Nuwin-P, Pecomin-PG, Prebel-M, Predic-GM, Pregacent-M, Pregamet, Preganerv-M, Pregeb-M OD, Pregmic, Prejunate Plus, Preneurolin Plus, Pretek-GM, Rejusite, Renerve-P, Safyvit-PR, Vitcobin-P, and Voltanerv with Methylcobalamin and ALA by Cogentrix Pharma.[145]

In the US, Lyrica is marketed by Viatris after Upjohn was spun off from Pfizer.[146][147][148]

References

edit- ^ "Pregabalin". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ^ "Avoid prescribing pregabalin in pregnancy if possible". Australian Department of Health and Aged Care. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ "Product Information safety updates - January 2023". Australian Department of Health and Aged Care. Archived from the original on February 13, 2023. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Schifano F (June 2014). "Misuse and abuse of pregabalin and gabapentin: cause for concern?". CNS Drugs. 28 (6): 491–496. doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0164-4. PMID 24760436.

- ^ "Prescription medicines: registration of new generic medicines and biosimilar medicines, 2017". Therapeutic Goods Administration (TGA). June 21, 2022. Archived from the original on July 6, 2023. Retrieved March 30, 2024.

- ^ Anvisa (March 31, 2023). "RDC Nº 784 - Listas de Substâncias Entorpecentes, Psicotrópicas, Precursoras e Outras sob Controle Especial" [Collegiate Board Resolution No. 784 - Lists of Narcotic, Psychotropic, Precursor, and Other Substances under Special Control] (in Brazilian Portuguese). Diário Oficial da União (published April 4, 2023). Archived from the original on August 3, 2023. Retrieved August 16, 2023.

- ^ "Lyrica Consumer Medicine Information" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on December 4, 2023. Retrieved December 4, 2023.

- ^ "Lyrica Summary of Product Characteristics (SmPC)". (emc). February 27, 2023. Archived from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c "Lyrica- pregabalin capsule Lyrica- pregabalin solution". DailyMed. June 15, 2020. Archived from the original on September 25, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ "Lyrica EPAR". European Medicines Agency (EMA). July 6, 2004. Archived from the original on December 21, 2023. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Summary of product characteristics" (PDF). European Medicines Agency (EMA). March 6, 2013. Archived (PDF) from the original on September 16, 2018. Retrieved May 6, 2013.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Bockbrader HN, Radulovic LL, Posvar EL, Strand JC, Alvey CW, Busch JA, et al. (August 2010). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of pregabalin in healthy volunteers". Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 50 (8): 941–950. doi:10.1177/0091270009352087. PMID 20147618. S2CID 9905501.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Pregabalin". The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists. Archived from the original on December 2, 2019. Retrieved February 3, 2019.

- ^ a b Expert Committee on Drug Dependence Forty-first Meeting (November 2018). Critical Review Report: Pregabalin (PDF) (Report). Geneva: World Health Organization. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 26, 2020.

- ^ Cross AL, Viswanath O, Sherman AI (July 19, 2022). "Pregabalin". StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. PMID 29261857. Archived from the original on August 3, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022 – via NCBI Bookshelf.

- ^ "BNF Pregabalin". NICE. November 16, 2018. Retrieved June 19, 2024.

- ^ Frampton JE (September 2014). "Pregabalin: a review of its use in adults with generalized anxiety disorder". CNS Drugs. 28 (9): 835–854. doi:10.1007/s40263-014-0192-0. PMID 25149863. S2CID 5349255.

- ^ Iftikhar IH, Alghothani L, Trotti LM (December 2017). "Gabapentin enacarbil, pregabalin and rotigotine are equally effective in restless legs syndrome: a comparative meta-analysis". European Journal of Neurology. 24 (12): 1446–1456. doi:10.1111/ene.13449. PMID 28888061. S2CID 22262972.

- ^ a b Wyllie E, Cascino GD, Gidal BE, Goodkin HP (February 17, 2012). Wyllie's Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 423. ISBN 978-1-4511-5348-4.

- ^ Kirsch D (October 10, 2013). Sleep Medicine in Neurology. John Wiley & Sons. p. 241. ISBN 978-1-118-76417-6.

- ^ Frye M, Moore K (2009). "Gabapentin and Pregabalin". In Schatzberg AF, Nemeroff CB (eds.). The American Psychiatric Publishing Textbook of Psychopharmacology. pp. 767–77. doi:10.1176/appi.books.9781585623860.as38. ISBN 978-1-58562-309-9. Archived from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved September 1, 2022.

- ^ a b Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M (2016). "Alpha2delta ligands, gabapentin, pregabalin and mirogabalin: a review of their clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use". Expert Rev Neurother. 16 (11): 1263–1277. doi:10.1080/14737175.2016.1202764. PMID 27345098. S2CID 33200190.

- ^ a b c d e Dooley DJ, Taylor CP, Donevan S, Feltner D (2007). "Ca2+ channel alpha2delta ligands: novel modulators of neurotransmission". Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 28 (2): 75–82. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2006.12.006. PMID 17222465.

- ^ a b Elaine Wyllie, Gregory D. Cascino, Barry E. Gidal, Howard P. Goodkin (February 17, 2012). Wyllie's Treatment of Epilepsy: Principles and Practice. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 423. ISBN 978-1-4511-5348-4.

- ^ a b c d Honorio Benzon, James P. Rathmell, Christopher L. Wu, Dennis C. Turk, Charles E. Argoff, Robert W Hurley (September 11, 2013). Practical Management of Pain. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 1006. ISBN 978-0-323-17080-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Calandre EP, Rico-Villademoros F, Slim M (November 2016). "Alpha2delta ligands, gabapentin, pregabalin and mirogabalin: a review of their clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 16 (11): 1263–1277. doi:10.1080/14737175.2016.1202764. PMID 27345098. S2CID 33200190.

- ^ a b c Uchitel OD, Di Guilmi MN, Urbano FJ, Gonzalez-Inchauspe C (2010). "Acute modulation of calcium currents and synaptic transmission by gabapentinoids". Channels. 4 (6): 490–496. doi:10.4161/chan.4.6.12864. hdl:11336/20897. PMID 21150315.

- ^ Mishriky BM, Waldron NH, Habib AS (January 2015). "Impact of pregabalin on acute and persistent postoperative pain: a systematic review and meta-analysis". British Journal of Anaesthesia. 114 (1): 10–31. doi:10.1093/bja/aeu293. PMID 25209095.

- ^ a b c British National Formulary: BNF 76 (76 ed.). Pharmaceutical Press. 2018. p. 323. ISBN 9780857113382.

- ^ "Pregabalin Use During Pregnancy". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ Kaye AD, Vadivelu N, Urman RD (2014). Substance Abuse: Inpatient and Outpatient Management for Every Clinician. Springer. p. 324. ISBN 9781493919512. Archived from the original on March 1, 2022. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ a b "Generic Lyrica Availability". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on March 27, 2019. Retrieved February 4, 2019.

- ^ "FDA approves first generics of Lyrica". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) (Press release). September 11, 2019. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved October 27, 2019.

- ^ "Pregabalin ER: FDA-Approved Drugs". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Archived from the original on June 24, 2021. Retrieved June 19, 2021.

- ^ "Competitive Generic Therapy Approvals". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). June 29, 2023. Archived from the original on June 29, 2023. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- ^ "The Top 300 of 2022". ClinCalc. Archived from the original on August 30, 2024. Retrieved August 30, 2024.

- ^ "Pregabalin Drug Usage Statistics, United States, 2013 - 2022". ClinCalc. Retrieved August 30, 2024.

- ^ "Is Lyrica a Controlled Substance?". Archived from the original on May 6, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ "Is Lyrica a controlled substance / Narcotic?". Archived from the original on February 4, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ Preuss CV, Kalava A, King KC (2024). Prescription of Controlled Substances: Benefits and Risks. PMID 30726003.

- ^ a b "Pregabalin and gabapentin to be controlled as Class C drugs". GOV.UK. October 15, 2018. Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ "Controlled Drug Classes". August 12, 2013. Archived from the original on March 28, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ "What are Class C Drugs?". October 31, 2022. Archived from the original on May 6, 2024. Retrieved May 6, 2024.

- ^ a b "Control of pregabalin and gabapentin under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971". Archived from the original on February 21, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Pregabalin and gabapentin to be controlled as class C drugs". Archived from the original on November 12, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Panebianco M, Bresnahan R, Marson AG (March 2022). "Pregabalin add-on for drug-resistant focal epilepsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 3 (3): CD005612. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005612.pub5. PMC 8962962. PMID 35349176.

- ^ a b Zhou Q, Zheng J, Yu L, Jia X (October 2012). "Pregabalin monotherapy for epilepsy". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10: CD009429. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009429.pub2. PMID 23076957.

- ^ Attal N, Cruccu G, Baron R, Haanpää M, Hansson P, Jensen TS, et al. (September 2010). "EFNS guidelines on the pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain: 2010 revision". European Journal of Neurology. 17 (9): 1113–1e88. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.02999.x. PMID 20402746. S2CID 14236933.

- ^ a b Derry S, Bell RF, Straube S, Wiffen PJ, Aldington D, Moore RA (January 2019). "Pregabalin for neuropathic pain in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 1 (1): CD007076. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007076.pub3. PMC 6353204. PMID 30673120.

- ^ Finnerup NB, Sindrup SH, Jensen TS (September 2010). "The evidence for pharmacological treatment of neuropathic pain". Pain. 150 (3): 573–581. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.019. PMID 20705215. S2CID 29830155.

- ^ "Combination therapy for painful diabetic neuropathy is safe and effective". NIHR Evidence. April 6, 2023. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_57470. S2CID 258013544. Archived from the original on April 28, 2023. Retrieved April 28, 2023.

- ^ Tesfaye S, Sloan G, Petrie J, White D, Bradburn M, Julious S, et al. (August 2022). "Comparison of amitriptyline supplemented with pregabalin, pregabalin supplemented with amitriptyline, and duloxetine supplemented with pregabalin for the treatment of diabetic peripheral neuropathic pain (OPTION-DM): a multicentre, double-blind, randomised crossover trial". Lancet. 400 (10353): 680–690. doi:10.1016/s0140-6736(22)01472-6. PMC 9418415. PMID 36007534.

- ^ Freynhagen R, Baron R, Kawaguchi Y, Malik RA, Martire DL, Parsons B, et al. (January 2021). "Pregabalin for neuropathic pain in primary care settings: recommendations for dosing and titration" (PDF). Postgraduate Medicine. 133 (1). Informa UK Limited: 1–9. doi:10.1080/00325481.2020.1857992. PMID 33423590. S2CID 231574963. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 27, 2024. Retrieved February 19, 2024.

- ^ Bennett MI, Laird B, van Litsenburg C, Nimour M (November 2013). "Pregabalin for the management of neuropathic pain in adults with cancer: a systematic review of the literature". Pain Medicine. 14 (11): 1681–1688. doi:10.1111/pme.12212. PMID 23915361.

- ^ Howard P (2017). Palliative care formulary (6 ed.). Pharmaceutical press. p. Chapter 4 Central Nervous System. ISBN 978-0-85711-348-1.

- ^ a b Clarke H, Bonin RP, Orser BA, Englesakis M, Wijeysundera DN, Katz J (August 2012). "The prevention of chronic postsurgical pain using gabapentin and pregabalin: a combined systematic review and meta-analysis". Anesthesia and Analgesia. 115 (2): 428–442. doi:10.1213/ANE.0b013e318249d36e. hdl:10315/27968. PMID 22415535. S2CID 18933131.

- ^ Chaparro LE, Smith SA, Moore RA, Wiffen PJ, Gilron I (July 2013). "Pharmacotherapy for the prevention of chronic pain after surgery in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (7): CD008307. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008307.pub2. PMC 6481826. PMID 23881791.

- ^ Hamilton TW, Strickland LH, Pandit HG (August 2016). "A Meta-Analysis on the Use of Gabapentinoids for the Treatment of Acute Postoperative Pain Following Total Knee Arthroplasty". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery. American Volume. 98 (16): 1340–1350. doi:10.2106/jbjs.15.01202. PMID 27535436. Archived from the original on September 29, 2020. Retrieved August 24, 2020.

- ^ Patel R, Dickenson AH (April 2016). "Mechanisms of the gabapentinoids and α 2 δ-1 calcium channel subunit in neuropathic pain". Pharmacology Research & Perspectives. 4 (2): e00205. doi:10.1002/prp2.205. PMC 4804325. PMID 27069626.

- ^ a b Slee A, Nazareth I, Bondaronek P, Liu Y, Cheng Z, Freemantle N (February 2019). "Pharmacological treatments for generalised anxiety disorder: a systematic review and network meta-analysis" (PDF). Lancet. 393 (10173): 768–777. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31793-8. PMID 30712879. S2CID 72332967. Archived (PDF) from the original on March 13, 2020. Retrieved September 8, 2020.; "Supplemental Appendices" (PDF). June 5, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 9, 2020.; "Authors' Reply" (PDF). June 5, 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 17, 2020.

- ^ "Review finds little evidence to support gabapentinoid use in bipolar disorder or insomnia". NIHR Evidence (Plain English summary). National Institute for Health and Care Research. October 17, 2022. doi:10.3310/nihrevidence_54173. S2CID 252983016. Archived from the original on November 27, 2022. Retrieved October 27, 2022.

- ^ a b c Hong JS, Atkinson LZ, Al-Juffali N, Awad A, Geddes JR, Tunbridge EM, et al. (March 2022). "Gabapentin and pregabalin in bipolar disorder, anxiety states, and insomnia: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and rationale". Molecular Psychiatry. 27 (3): 1339–1349. doi:10.1038/s41380-021-01386-6. PMC 9095464. PMID 34819636.

- ^ Hong JS, Atkinson LZ, Al-Juffali N, Awad A, Geddes JR, Tunbridge EM, et al. (March 2022). "Gabapentin and pregabalin in bipolar disorder, anxiety states, and insomnia: Systematic review, meta-analysis, and rationale". Molecular Psychiatry. 27 (3): 1339–1349. doi:10.1038/s41380-021-01386-6. PMC 9095464. PMID 34819636.

- ^ Bandelow B, Sher L, Bunevicius R, Hollander E, Kasper S, Zohar J, et al. (June 2012). "Guidelines for the pharmacological treatment of anxiety disorders, obsessive-compulsive disorder and posttraumatic stress disorder in primary care" (PDF). International Journal of Psychiatry in Clinical Practice. 16 (2): 77–84. doi:10.3109/13651501.2012.667114. PMID 22540422. S2CID 16253034. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 3, 2018. Retrieved October 16, 2020.

- ^ Wensel TM, Powe KW, Cates ME (March 2012). "Pregabalin for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder". The Annals of Pharmacotherapy. 46 (3): 424–429. doi:10.1345/aph.1Q405. PMID 22395254. S2CID 26320851.

- ^ a b Owen RT (September 2007). "Pregabalin: its efficacy, safety and tolerability profile in generalized anxiety". Drugs of Today. 43 (9): 601–610. doi:10.1358/dot.2007.43.9.1133188. PMID 17940637.

- ^ "How long does it take for Lyrica to work?". Drugs.com. May 25, 2021. Archived from the original on February 18, 2022. Retrieved February 18, 2022.

- ^ a b c d Bandelow B, Wedekind D, Leon T (July 2007). "Pregabalin for the treatment of generalized anxiety disorder: a novel pharmacologic intervention". Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics. 7 (7): 769–781. doi:10.1586/14737175.7.7.769. PMID 17610384. S2CID 6229344.

- ^ Ng QX, Han MX, Teoh SE, Yaow CY, Lim YL, Chee KT (August 2021). "A Systematic Review of the Clinical Use of Gabapentin and Pregabalin in Bipolar Disorder". Pharmaceuticals. 14 (9): 834. doi:10.3390/ph14090834. PMC 8469561. PMID 34577534.

- ^ Giménez-Campos MS, Pimenta-Fermisson-Ramos P, Díaz-Cambronero JI, Carbonell-Sanchís R, López-Briz E, Ruíz-García V (January 2022). "A systematic review and meta-analysis of the effectiveness and adverse events of gabapentin and pregabalin for sciatica pain". Atencion Primaria. 54 (1). Elsevier BV: 102144. doi:10.1016/j.aprim.2021.102144. PMC 8515246. PMID 34637958.

- ^ Shanthanna H, Gilron I, Rajarathinam M, AlAmri R, Kamath S, Thabane L, et al. (August 2017). "Benefits and safety of gabapentinoids in chronic low back pain: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". PLOS Medicine. 14 (8): e1002369. doi:10.1371/journal.pmed.1002369. PMC 5557428. PMID 28809936.

- ^ Mannix L (December 18, 2018). "This popular drug is linked to addiction and suicide. Why do doctors keep prescribing it?". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on December 18, 2018. Retrieved December 18, 2018.

- ^ Freynhagen R, Backonja M, Schug S, Lyndon G, Parsons B, Watt S, et al. (December 2016). "Pregabalin for the Treatment of Drug and Alcohol Withdrawal Symptoms: A Comprehensive Review". CNS Drugs. 30 (12): 1191–1200. doi:10.1007/s40263-016-0390-z. PMC 5124051. PMID 27848217.

- ^ Linde M, Mulleners WM, Chronicle EP, McCrory DC (June 2013). "Gabapentin or pregabalin for the prophylaxis of episodic migraine in adults". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD010609. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010609. PMC 6599858. PMID 23797675.

- ^ Onakpoya IJ, Thomas ET, Lee JJ, Goldacre B, Heneghan CJ (January 2019). "Benefits and harms of pregabalin in the management of neuropathic pain: a rapid review and meta-analysis of randomised clinical trials". BMJ Open. 9 (1): e023600. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-023600. PMC 6347863. PMID 30670513.

- ^ a b c "Schedules of Controlled Substances: Placement of Pregabalin Into Schedule V". Federal Register. July 28, 2005. Archived from the original on August 2, 2021. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ Slocum GW, Schult RF, Gorodetsky RM, Wiegand TJ, Kamali M, Acquisto NM (January 1, 2018). "Pregabalin and paradoxical reaction of seizures in a large overdose". Toxicology Communications. 2 (1): 19–20. doi:10.1080/24734306.2018.1458465. S2CID 79760296.

- ^ Lyrica (Australian Approved Product Information), Pfizer Australia Pty Ltd., 2006, archived from the original on March 13, 2018

- ^ Rossi S, ed. (2006). Australian Medicines Handbook, 2006. Australian Medicines Handbook. ISBN 978-0-9757919-2-9.[page needed]

- ^ "Medication Guide (Pfizer Inc.)" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). June 2011. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 8, 2011. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ Millar J, Sadasivan S, Weatherup N, Lutton S (September 7, 2013). "Lyrica Nights–Recreational Pregabalin Abuse in an Urban Emergency Department". Emergency Medicine Journal. 30 (10): 874.2–874. doi:10.1136/emermed-2013-203113.20. S2CID 73986091.

- ^ "Lyrica Capsules". medicines.org.uk. Archived from the original on October 20, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ "Pregabalin Pregnancy and Breastfeeding Warnings". Archived from the original on March 21, 2019. Retrieved August 29, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "FDA warns about serious breathing problems with seizure and nerve pain medicines gabapentin (Neurontin, Gralise, Horizant) and pregabalin (Lyrica, Lyrica CR) When used with CNS depressants or in patients with lung problems". U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). December 19, 2019. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "FDA warns about serious breathing problems with seizure and nerve pain medicines gabapentin (Neurontin, Gralise, Horizant) and pregabalin (Lyrica, Lyrica CR) When used with CNS depressants or in patients with lung problems" (PDF). U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). December 19, 2019. Archived from the original on December 22, 2019. This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Tanyıldız B, Kandemir B, Mangan MS, Tangılntız A, Göktaş E, Şimşek S (October 2018). "Bilateral Serous Macular Detachment After Attempted Suicide with Pregabalin". Turkish Journal of Ophthalmology. 48 (5): 254–257. doi:10.4274/tjo.70923. PMC 6216534. PMID 30405948.

- ^ Desai A, Kherallah Y, Szabo C, Marawar R (March 2019). "Gabapentin or pregabalin induced myoclonus: A case series and literature review". Journal of Clinical Neuroscience. 61: 225–234. doi:10.1016/j.jocn.2018.09.019. PMID 30381161. S2CID 53165515.

- ^ Murphy NG, Mosher L (2008). "79. Severe myoclonus from pregabalin (Lyrica) due to chronic renal insufficiency". Clinical Toxicology. 46 (7): 604. doi:10.1080/15563650802255033. S2CID 218857181.

- ^ Yoo L, Matalon D, Hoffman RS, Goldfarb DS (December 2009). "Treatment of pregabalin toxicity by hemodialysis in a patient with kidney failure" (PDF). American Journal of Kidney Diseases. 54 (6): 1127–1130. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.955.4223. doi:10.1053/j.ajkd.2009.04.014. PMID 19493601. Archived from the original on April 12, 2022. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ Baselt RC (2008). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (8th ed.). Biomedical Publications. pp. 1296–1297. ISBN 978-0-9626523-7-0.

- ^ "Pregabalin". Lexi-Drugs [database on the Internet. Hudson (OH): Lexi-Comp, Inc. 2007. Archived from the original on October 19, 2020. Retrieved October 29, 2015..

- ^ a b Holsboer-Trachsler E, Prieto R (May 1, 2013). "Effects of pregabalin on sleep in generalized anxiety disorder". International Journal of Neuropsychopharmacology. 16 (4): 925–936. doi:10.1017/S1461145712000922. PMID 23009881.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Sills GJ (February 2006). "The mechanisms of action of gabapentin and pregabalin". Current Opinion in Pharmacology. 6 (1): 108–113. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2005.11.003. PMID 16376147.

- ^ a b c Bryans JS, Wustrow DJ (March 1999). "3-substituted GABA analogs with central nervous system activity: a review". Medicinal Research Reviews. 19 (2): 149–177. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1098-1128(199903)19:2<149::AID-MED3>3.0.CO;2-B. PMID 10189176. S2CID 38496241.

- ^ Lin GQ, You QD, Cheng JF, eds. (August 8, 2011). Chiral Drugs: Chemistry and Biological Action. John Wiley & Sons. p. 88. ISBN 9781118075630. Archived from the original on April 25, 2022. Retrieved August 17, 2016 – via Google Books.

- ^ Li Z, Taylor CP, Weber M, Piechan J, Prior F, Bian F, et al. (September 2011). "Pregabalin is a potent and selective ligand for α(2)δ-1 and α(2)δ-2 calcium channel subunits". European Journal of Pharmacology. 667 (1–3): 80–90. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2011.05.054. PMID 21651903. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 20, 2020.

- ^ Sze PY (1979). "L-Glutamate Decarboxylase". GABA—Biochemistry and CNS Functions. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Vol. 123. pp. 59–78. doi:10.1007/978-1-4899-5199-1_4 (inactive November 1, 2024). ISBN 978-1-4899-5201-1. PMID 390996.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ a b c Stahl SM, Porreca F, Taylor CP, Cheung R, Thorpe AJ, Clair A (June 2013). "The diverse therapeutic actions of pregabalin: is a single mechanism responsible for several pharmacological activities?". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 34 (6): 332–339. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2013.04.001. PMID 23642658.

- ^ a b Davies A, Hendrich J, Van Minh AT, Wratten J, Douglas L, Dolphin AC (May 2007). "Functional biology of the alpha(2)delta subunits of voltage-gated calcium channels". Trends in Pharmacological Sciences. 28 (5): 220–228. doi:10.1016/j.tips.2007.03.005. PMID 17403543. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ Baidya DK, Agarwal A, Khanna P, Arora MK (July 2011). "Pregabalin in acute and chronic pain". Journal of Anaesthesiology Clinical Pharmacology. 27 (3): 307–314. doi:10.4103/0970-9185.83672. PMC 3161452. PMID 21897498.

- ^ McMahon SB (2013). Wall and Melzack's textbook of pain (6th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. p. 515. ISBN 9780702040597.

- ^ Taylor CP, Angelotti T, Fauman E (February 2007). "Pharmacology and mechanism of action of pregabalin: the calcium channel alpha2-delta (alpha2-delta) subunit as a target for antiepileptic drug discovery". Epilepsy Research. 73 (2): 137–150. doi:10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2006.09.008. PMID 17126531. S2CID 54254671. Archived from the original on October 23, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ a b Lauria-Horner BA, Pohl RB (April 2003). "Pregabalin: a new anxiolytic". Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs. 12 (4): 663–672. doi:10.1517/13543784.12.4.663. PMID 12665421. S2CID 36137322.

- ^ a b c d Dickens D, Webb SD, Antonyuk S, Giannoudis A, Owen A, Rädisch S, et al. (June 2013). "Transport of gabapentin by LAT1 (SLC7A5)". Biochemical Pharmacology. 85 (11): 1672–1683. doi:10.1016/j.bcp.2013.03.022. PMID 23567998. Archived from the original on October 21, 2020. Retrieved October 19, 2020.

- ^ del Amo EM, Urtti A, Yliperttula M (October 2008). "Pharmacokinetic role of L-type amino acid transporters LAT1 and LAT2". European Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences. 35 (3): 161–174. doi:10.1016/j.ejps.2008.06.015. PMID 18656534.

- ^ a b Geldenhuys WJ, Mohammad AS, Adkins CE, Lockman PR (2015). "Molecular determinants of blood-brain barrier permeation". Therapeutic Delivery. 6 (8): 961–971. doi:10.4155/tde.15.32. PMC 4675962. PMID 26305616.

- ^ a b Müller CE (November 2009). "Prodrug approaches for enhancing the bioavailability of drugs with low solubility". Chemistry & Biodiversity. 6 (11): 2071–2083. doi:10.1002/cbdv.200900114. PMID 19937841. S2CID 32513471.

- ^ Boado RJ, Li JY, Nagaya M, Zhang C, Pardridge WM (October 1999). "Selective expression of the large neutral amino acid transporter at the blood-brain barrier". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 96 (21): 12079–12084. Bibcode:1999PNAS...9612079B. doi:10.1073/pnas.96.21.12079. PMC 18415. PMID 10518579.

- ^ McElroy SL, Keck PE, Post RM, eds. (2008). Antiepileptic Drugs to Treat Psychiatric Disorders. INFRMA-HC. p. 370. ISBN 978-0-8493-8259-8.

- ^ Ma J, Björnsson ES, Chalasani N (February 2024). "The Safe Use of Analgesics in Patients with Cirrhosis: A Narrative Review". Am J Med. 137 (2): 99–106. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2023.10.022. PMID 37918778. S2CID 264888110.

- ^ a b Yogeeswari P, Ragavendran JV, Sriram D (January 2006). "An update on GABA analogs for CNS drug discovery". Recent Patents on CNS Drug Discovery. 1 (1): 113–118. doi:10.2174/157488906775245291. PMID 18221197.

- ^ Rose MA, Kam PC (May 2002). "Gabapentin: pharmacology and its use in pain management". Anaesthesia. 57 (5): 451–462. doi:10.1046/j.0003-2409.2001.02399.x. PMID 11966555. S2CID 27431734.

- ^ Wheless JW, Willmore J, Brumback RA (2009). Advanced Therapy in Epilepsy. PMPH-USA. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-60795-004-2.

- ^ Vardanyan R, Hruby V (January 7, 2016). Synthesis of Best-Seller Drugs. Elsevier Science. p. 158. ISBN 978-0-12-411524-8. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Andrushko V, Andrushko N (August 16, 2013). Stereoselective Synthesis of Drugs and Natural Products. John Wiley & Sons. p. 869. ISBN 978-1-118-62833-1. Archived from the original on August 29, 2021. Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- ^ Lowe D (March 25, 2008). "Getting to Lyrica". In the Pipeline. Science. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved November 21, 2015.

- ^ a b Merrill N (February 25, 2010). "Silverman's golden drug makes him NU's golden ticket". North by Northwestern. Archived from the original on June 1, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- ^ Andruszkiewicz R, Silverman RB (December 1990). "4-Amino-3-alkylbutanoic acids as substrates for gamma-aminobutyric acid aminotransferase". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 265 (36): 22288–22291. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)45702-X. PMID 2266125. Archived from the original on August 27, 2022. Retrieved August 25, 2016.

- ^ Poros J (2005). "Polish scientist is the co-author of a new anti-epileptic drug". Science and Scholarship in Poland. Archived from the original on August 20, 2016. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- ^ Dworkin RH, Kirkpatrick P (June 2005). "Pregabalin". Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery. 4 (6): 455–456. doi:10.1038/nrd1756. PMID 15959952. S2CID 265702200. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "FDA approves LYRICA CR extended-release tablets CV". Seeking Alpha. October 12, 2017. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ^ "BRIEF-FDA approves Pfizer's Lyrica CR extended-release tablets CV". Reuters. Archived from the original on October 4, 2018. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ "Lyrica: Package Insert & Prescribing Information". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on August 13, 2017. Retrieved August 18, 2016.

- ^ "2005 - Placement of Pregabalin Into Schedule V". DEA Diversion Control Division. July 28, 2005. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved August 27, 2022.

- ^ "Title 21 CFR – PART 1308 – Section 1308.15 Schedule V". usdoj.gov. Archived from the original on September 3, 2020. Retrieved September 27, 2015.

- ^ "Lyrica". Felleskatalogen (in Norwegian). May 7, 2015. Archived from the original on December 23, 2016. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ Chalabianloo F, Schjøtt J (January 2009). "Pregabalin og misbrukspotensial" [Pregabalin and its potential for abuse]. Tidsskrift for den Norske Laegeforening (in Norwegian). 129 (3): 186–187. doi:10.4045/tidsskr.08.0047. PMID 19180163. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Re: Pregabalin and Gabapentin advice" (PDF). GOV.UK. January 14, 2016. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 8, 2020. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ "Pregabalin and gabapentin: proposal to schedule under the Misuse of Drugs Regulations 2001". GOV.UK. November 10, 2017. Archived from the original on January 3, 2020. Retrieved April 2, 2020.

- ^ Mayor S (October 2018). "Pregabalin and gabapentin become controlled drugs to cut deaths from misuse". BMJ. 363: k4364. doi:10.1136/bmj.k4364. PMID 30327316. S2CID 53520780. Archived from the original on August 9, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2019.

- ^ "Control of pregabalin and gabapentin under the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971". GOV.UK. March 29, 2019. Archived from the original on February 21, 2024. Retrieved February 21, 2024.

- ^ "Pfizer to pay $2.3 billion to resolve criminal and civil health care liability relating to fraudulent marketing and the payment of kickbacks". Stop Medicare Fraud, U.S. Departments of Health & Human Services, and of Justice. Archived from the original on August 30, 2012. Retrieved July 4, 2012.

- ^ a b Levy S (July 22, 2019), "Nine generic firms get FDA approval for generic Lyrica.", Drug Store News, archived from the original on August 5, 2020

- ^ "Pfizer's Lyrica Approved for the Treatment of Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD) in Europe" (Press release). Archived from the original on September 29, 2007. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ "Generic Lyrica launches at 97% discount to brand version". 46brooklyn Research. July 23, 2019. Archived from the original on July 16, 2020. Retrieved December 25, 2019.

- ^ Bulik BS (March 2016). "AbbVie's Humira, Pfizer's Lyrica kick off 2016 with hefty TV ad spend". FiercePharma. Archived from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ^ a b Harris G (September 2, 2009). "Pfizer Pays $2.3 Billion to Settle Marketing Case". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 26, 2020. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ a b "Pfizer agrees record fraud fine". BBC News. September 2, 2009. Archived from the original on September 8, 2009. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ "Portions of the Pfizer Inc. 2010 Financial Report". U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission. 2010. Archived from the original on June 10, 2019. Retrieved December 21, 2017.

- ^ Jacoby M (2008). "Financial Windfall from Lyrica". Chemical & Engineering News. 86 (10): 56–61. doi:10.1021/cen-v086n010.p056. Archived from the original on October 26, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ US 6197819B1, Silverman RB, Andruszkiewicz R, "Gamma amino butyric acid analogs and optical isomers", issued March 6, 2001, assigned to Northwestern University Archived March 21, 2019, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Decker S (February 6, 2014). "Pfizer Wins Ruling to Block Generic Lyrica Until 2018". Bloomberg. Archived from the original on February 8, 2014. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Decision: Pfizer Inc. (PFE) v. Teva Pharmaceuticals USA Inc., 12-1576, U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (Washington)" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on October 29, 2020. Retrieved October 26, 2020.

- ^ "Pfizer's failed pregabalin patent appeal means NHS could reclaim £502m". Pulse. November 14, 2018. Archived from the original on November 15, 2018. Retrieved May 17, 2024.

- ^ a b "Pregabalin international brands". Drugs.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2019. Retrieved October 27, 2017.

- ^ "Pfizer Completes Transaction to Combine Its Upjohn Business with Mylan". Pfizer. November 16, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2024 – via Business Wire.

- ^ "Lyrica". Pfizer. Retrieved June 17, 2024.

- ^ "Brands". Viatris. November 16, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2024.