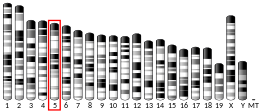

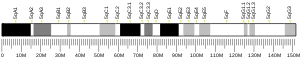

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP, α-fetoprotein; also sometimes called alpha-1-fetoprotein, alpha-fetoglobulin, or alpha fetal protein) is a protein[5][6] that in humans is encoded by the AFP gene.[7][8] The AFP gene is located on the q arm of chromosome 4 (4q13.3).[9] Maternal AFP serum level is used to screen for Down syndrome, neural tube defects, and other chromosomal abnormalities.[10]

| AFP | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Aliases | AFP, AFPD, FETA, HPalpha fetoprotein | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| External IDs | OMIM: 104150; MGI: 87951; HomoloGene: 36278; GeneCards: AFP; OMA:AFP - orthologs | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Wikidata | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

AFP is a major plasma protein produced by the yolk sac and the fetal liver during fetal development. It is thought to be the fetal analog of serum albumin. AFP binds to copper, nickel, fatty acids and bilirubin[8] and is found in monomeric, dimeric and trimeric forms.

Structure

editAFP is a glycoprotein of 591 amino acids[11] and a carbohydrate moiety.[12]

Function

editThe function of AFP in adult humans is unknown. AFP is the most abundant plasma protein found in the human fetus. In the fetus, AFP is produced by both the liver and the yolk sac. It is believed to function as a carrier protein (similar to albumin) that transports materials such as fatty acids to cells.[13] Maternal plasma levels peak near the end of the first trimester, and begin decreasing prenatally at that time, then decrease rapidly after birth. Normal adult levels in the newborn are usually reached by the age of 8 to 12 months. While the function in humans is unknown, in rodents it binds estradiol to prevent the transport of this hormone across the placenta to the fetus. The main function of this is to prevent the virilization of female fetuses. As human AFP does not bind estrogen, its function in humans is less clear.[14] In human liver cancer, AFP is found to bind glypican-3 (GPC3), another oncofetal antigen.[15]

The rodent AFP system can be overridden with massive injections of estrogen, which overwhelm the AFP system and will masculinize the fetus. The masculinizing effect of estrogens may seem counter-intuitive since estrogens are critical for the proper development of female secondary characteristics during puberty. However, this is not the case prenatally. Gonadal hormones from the testes, such as testosterone and anti-Müllerian hormone, are required to cause development of a phenotypic male. Without these hormones, the fetus will develop into a phenotypic female even if genetically XY. The conversion of testosterone into estradiol by aromatase in many tissues may be an important step in masculinization of that tissue.[16][17] Masculinization of the brain is thought to occur both by conversion of testosterone into estradiol by aromatase, but also by de novo synthesis of estrogens within the brain.[18][19] Thus, AFP may protect the fetus from maternal estradiol that would otherwise have a masculinizing effect on the fetus, but its exact role is still controversial.

Serum levels

editMaternal

editIn pregnant women, fetal AFP levels can be monitored in the urine of the pregnant woman. Since AFP is quickly cleared from the mother's serum via her kidneys, maternal urine AFP correlates with fetal serum levels, although the maternal urine level is much lower than the fetal serum level. AFP levels rise until about week 32. Maternal serum alpha-fetoprotein (MSAFP) screening is performed at 16 to 18 weeks of gestation.[20] If MSAFP levels indicate an anomaly, amniocentesis may be offered to the patient.

Infants

editThe normal range of AFP for adults and children is variously reported as under 50, under 10, or under 5 ng/mL.[21][22] At birth, normal infants have AFP levels four or more orders of magnitude above this normal range, that decreases to a normal range over the first year of life.[23][24][25][26][27][28]

During this time, the normal range of AFP levels spans approximately two orders of magnitude.[25] Correct evaluation of abnormal AFP levels in infants must take into account these normal patterns.[25]

Very high AFP levels may be subject to hooking (see Tumor marker), which results in the level being reported significantly lower than the actual concentration.[29] This is important for analysis of a series of AFP tumor marker tests, e.g. in the context of post-treatment early surveillance of cancer survivors, where the rate of decrease of AFP has diagnostic value.

Clinical significance

editMeasurement of AFP is generally used in two clinical contexts. First, it is measured in pregnant women through the analysis of maternal blood or amniotic fluid as a screening test for certain developmental abnormalities, such as aneuploidy. Second, serum AFP level is elevated in people with certain tumors, and so it is used as a biomarker to follow these diseases. Some of these diseases are listed below:

- Developmental birth defects associated with elevated AFP

- Omphalocele[30][31]

- Gastroschisis

- Neural tube defects: ↑ α-fetoprotein in amniotic fluid and maternal serum[32][33]

- Tumors associated with elevated AFP

- Hepatocellular carcinoma[32][34]

- Metastatic disease affecting the liver

- Nonseminomatous germ cell tumors

- Yolk sac tumor[32]

- Other conditions associated with elevated AFP

- Ataxia telangiectasia: elevated AFP is used as one factor in diagnosis[35]

A peptide derived from AFP that is referred to as AFPep is claimed to possess anti-cancer properties.[36]

In the treatment of testicular cancer it is paramount to differentiate seminomatous and nonseminomatous tumors. This is typically done pathologically after removal of the testicle and confirmed by tumor markers. However, if the pathology is pure seminoma, if the AFP is elevated, the tumor is treated as a nonseminomatous tumor because it contains yolk sac (nonseminomatous) components.[37]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000081051 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000054932 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Tomasi TB (1977). "Structure and function of alpha-fetoprotein". Annual Review of Medicine. 28: 453–65. doi:10.1146/annurev.me.28.020177.002321. PMID 67821.

- ^ Mizejewski GJ (May 2001). "Alpha-fetoprotein structure and function: relevance to isoforms, epitopes, and conformational variants". Experimental Biology and Medicine. 226 (5): 377–408. doi:10.1177/153537020122600503. PMID 11393167. S2CID 23763069.

- ^ Harper ME, Dugaiczyk A (July 1983). "Linkage of the evolutionarily-related serum albumin and alpha-fetoprotein genes within q11-22 of human chromosome 4". American Journal of Human Genetics. 35 (4): 565–72. PMC 1685723. PMID 6192711.

- ^ a b "Entrez Gene: Alpha-fetoprotein".

- ^ "Entry - *104150 - ALPHA-FETOPROTEIN; AFP - OMIM". omim.org. Retrieved 2023-06-12.

- ^ Perry SE, Hockenberry MJ, Lowdermilk DL, Wilson D (2014). "8: Nursing Care of the Family During Pregnancy". Maternal Child Nursing Care (Fifth ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-09610-2. OCLC 858005418.

- ^ Pucci P, Siciliano R, Malorni A, Marino G, Tecce MF, Ceccarini C, Terrana B (May 1991). "Human alpha-fetoprotein primary structure: a mass spectrometric study". Biochemistry. 30 (20): 5061–6. doi:10.1021/bi00234a032. PMID 1709810.

- ^ Seregni E, Botti C, Bombardieri E (1995). "Biochemical characteristics and clinical applications of alpha-fetoprotein isoforms". Anticancer Research. 15 (4): 1491–9. PMID 7544570.

- ^ Chen H (1997). "Regulation and activities of alpha-fetoprotein". Crit Rev Eukaryot Gene Expr. 7 (1–2): 11–41. doi:10.1615/critreveukargeneexpr.v7.i1-2.20. PMID 9034713.

- ^ Carter CS (2002). "Neuroendocrinology of sexual behavior in the female". In Becker JB (ed.). Behavioral Endocrinology. Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press. pp. 88–89. ISBN 978-0-262-52321-9.

- ^ Zhang YF, Lin S, Xiao Z, Ho M (October 2024). "A proteomic atlas of glypican-3 interacting partners: Identification of alpha-fetoprotein and other extracellular proteins as potential immunotherapy targets in liver cancer". Proteoglycan Research. 2 (4). doi:10.1002/pgr2.70004. ISSN 2832-3556.

- ^ Nef S, Parada LF (December 2000). "Hormones in male sexual development". Genes & Development. 14 (24): 3075–86. doi:10.1101/gad.843800. PMID 11124800.

- ^ Elbrecht A, Smith RG (1992). "Aromatase enzyme activity and sex determination in chickens". Science. 255 (5043): 467–70. Bibcode:1992Sci...255..467E. doi:10.1126/science.1734525. PMID 1734525.

- ^ Bakker J, Baum MJ (2008). "Role for estradiol in female-typical brain and behavioral sexual differentiation". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 29 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2007.06.001. PMC 2373265. PMID 17720235.

- ^ Harding CF (2004). "Hormonal modulation of singing: hormonal modulation of the songbird brain and singing behavior". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 1016 (1): 524–39. Bibcode:2004NYASA1016..524H. doi:10.1196/annals.1298.030. PMID 15313793. S2CID 12457330.

- ^ Perry SE, et al. (2018). "Chapter 10: Assessment of High Risk Pregnancy". Maternal child nursing care : maternity pediatric (Sixth ed.). St. Louis, Missouri: Elsevier. ISBN 978-0-323-54938-7. OCLC 999441854.

- ^ Ball D, Rose E, Alpert E (March 1992). "Alpha-fetoprotein levels in normal adults". The American Journal of the Medical Sciences. 303 (3): 157–9. doi:10.1097/00000441-199203000-00004. PMID 1375809.

- ^ Sizaret P, Martel N, Tuyns A, Reynaud S (February 1977). "Mean alpha-fetoprotein values of 1,333 males over 15 years by age groups". Digestion. 15 (2): 97–103. doi:10.1159/000197990. PMID 65304.

- ^ Blohm ME, Vesterling-Hörner D, Calaminus G, Göbel U (1998). "Alpha 1-fetoprotein (AFP) reference values in infants up to 2 years of age". Pediatric Hematology and Oncology. 15 (2): 135–42. doi:10.3109/08880019809167228. PMID 9592840.

- ^ Ohama K, Nagase H, Ogino K, Tsuchida K, Tanaka M, Kubo M, Horita S, Kawakami K, Ohmori M (October 1997). "Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) levels in normal children". European Journal of Pediatric Surgery. 7 (5): 267–9. doi:10.1055/s-2008-1071168. PMID 9402482. S2CID 260137699.

- ^ a b c Lee PI, Chang MH, Chen DS, Lee CY (January 1989). "Serum alpha-fetoprotein levels in normal infants: a reappraisal of regression analysis and sex difference". Journal of Pediatric Gastroenterology and Nutrition. 8 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1097/00005176-198901000-00005. PMID 2471821. S2CID 21104946.

- ^ Blair JI, Carachi R, Gupta R, Sim FG, McAllister EJ, Weston R (April 1987). "Plasma alpha fetoprotein reference ranges in infancy: effect of prematurity". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 62 (4): 362–9. doi:10.1136/adc.62.4.362. PMC 1778344. PMID 2439023.

- ^ Bader D, Riskin A, Vafsi O, Tamir A, Peskin B, Israel N, Merksamer R, Dar H, David M (November 2004). "Alpha-fetoprotein in the early neonatal period--a large study and review of the literature". Clinica Chimica Acta. 349 (1–2): 15–23. doi:10.1016/j.cccn.2004.06.020. PMID 15469851.

- ^ Wu JT, Roan Y, Knight JA (1985). "Serum levels of AFP in normal infants: their clinical and physiological significance". In Mizejewski GJ, Porter I (eds.). Alfa-Fetoprotein and Congenital Disorders. New York: Academic Press. pp. 111–122.

- ^ Jassam N, Jones CM, Briscoe T, Horner JH (July 2006). "The hook effect: a need for constant vigilance". Annals of Clinical Biochemistry. 43 (Pt 4): 314–7. doi:10.1258/000456306777695726. PMID 16824284.

- ^ Szabó M, Veress L, Münnich A, Papp Z (September 1990). "[Alpha fetoprotein concentration in the amniotic fluid in normal pregnancy and in pregnancy complicated by fetal anomaly]". Orvosi Hetilap (in Hungarian). 131 (39): 2139–42. PMID 1699194.

- ^ Rosen T, D'Alton ME (December 2005). "Down syndrome screening in the first and second trimesters: what do the data show?". Seminars in Perinatology. 29 (6): 367–75. doi:10.1053/j.semperi.2006.01.001. PMID 16533649.

- ^ a b c Le, Tao. First Aid for the USMLE Step 1 2013. New York: McGraw-Hill Medical, 2013. Print.

- ^ Bredaki FE, Poon LC, Birdir C, Escalante D, Nicolaides KH (2012). "First-trimester screening for neural tube defects using alpha-fetoprotein". Fetal Diagnosis and Therapy. 31 (2): 109–14. doi:10.1159/000335677. PMID 22377693. S2CID 57465.

- ^ Ertle JM, Heider D, Wichert M, Keller B, Kueper R, Hilgard P, Gerken G, Schlaak JF (2013). "A combination of α-fetoprotein and des-γ-carboxy prothrombin is superior in detection of hepatocellular carcinoma". Digestion. 87 (2): 121–31. doi:10.1159/000346080. PMID 23406785. S2CID 25266129.

- ^ Taylor AM, Byrd PJ (October 2005). "Molecular pathology of ataxia telangiectasia". Journal of Clinical Pathology. 58 (10): 1009–15. doi:10.1136/jcp.2005.026062. PMC 1770730. PMID 16189143.

- ^ Mesfin FB, Bennett JA, Jacobson HI, Zhu S, Andersen TT (April 2000). "Alpha-fetoprotein-derived antiestrotrophic octapeptide". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - Molecular Basis of Disease. 1501 (1): 33–43. doi:10.1016/S0925-4439(00)00008-9. PMID 10727847.

- ^ Schmoldt A, Benthe HF, Haberland G (September 1975). "Digitoxin metabolism by rat liver microsomes". Biochem Pharmacol. 24 (17): 1639–41. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(75)90094-5. hdl:10033/333424. PMID 10.

Further reading

edit- Nahon JL (1987). "The regulation of albumin and alpha-fetoprotein gene expression in mammals". Biochimie. 69 (5): 445–59. doi:10.1016/0300-9084(87)90082-4. PMID 2445387.

- Tilghman SM (1989). "The structure and regulation of the alpha-fetoprotein and albumin genes". Oxford Surveys on Eukaryotic Genes. 2: 160–206. PMID 2474300.

- Mizejewski GJ (2003). "Biological role of alpha-fetoprotein in cancer: prospects for anticancer therapy". Expert Review of Anticancer Therapy. 2 (6): 709–35. doi:10.1586/14737140.2.6.709. PMID 12503217. S2CID 8321005.

- Yachnin S, Hsu R, Heinrikson RL, Miller JB (1977). "Studies on human alpha-fetoprotein. Isolation and characterization of monomeric and polymeric forms and amino-terminal sequence analysis". Biochimica et Biophysica Acta. 493 (2): 418–28. doi:10.1016/0005-2795(77)90198-2. PMID 70228.

- Aoyagi Y, Ikenaka T, Ichida F (1977). "Comparative chemical structures of human alpha-fetoproteins from fetal serum and from ascites fluid of a patient with hepatoma". Cancer Research. 37 (10): 3663–7. PMID 71198.

- Aoyagi Y, Ikenaka T, Ichida F (1978). "Copper(II)-binding ability of human alpha-fetoprotein". Cancer Research. 38 (10): 3483–6. PMID 80265.

- Aoyagi Y, Ikenaka T, Ichida F (1979). "alpha-Fetoprotein as a carrier protein in plasma and its bilirubin-binding ability". Cancer Research. 39 (9): 3571–4. PMID 89900.

- Torres JM, Anel A, Uriel J (1992). "Alpha-fetoprotein-mediated uptake of fatty acids by human T lymphocytes". Journal of Cellular Physiology. 150 (3): 456–62. doi:10.1002/jcp.1041500305. PMID 1371512. S2CID 32015210.

- Greenberg F, Faucett A, Rose E, et al. (1992). "Congenital deficiency of alpha-fetoprotein". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 167 (2): 509–11. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(11)91441-0. PMID 1379776.

- Bansal V, Kumari K, Dixit A, Sahib MK (1991). "Interaction of human alpha fetoprotein with bilirubin". Indian Journal of Experimental Biology. 28 (7): 697–8. PMID 1703124.

- Pucci P, Siciliano R, Malorni A, et al. (1991). "Human alpha-fetoprotein primary structure: a mass spectrometric study". Biochemistry. 30 (20): 5061–6. doi:10.1021/bi00234a032. PMID 1709810.

- Liu MC, Yu S, Sy J, et al. (1985). "Tyrosine sulfation of proteins from the human hepatoma cell line HepG2". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 82 (21): 7160–4. Bibcode:1985PNAS...82.7160L. doi:10.1073/pnas.82.21.7160. PMC 390808. PMID 2414772.

- Gibbs PE, Zielinski R, Boyd C, Dugaiczyk A (1987). "Structure, polymorphism, and novel repeated DNA elements revealed by a complete sequence of the human alpha-fetoprotein gene". Biochemistry. 26 (5): 1332–43. doi:10.1021/bi00379a020. PMID 2436661.

- Sakai M, Morinaga T, Urano Y, et al. (1985). "The human alpha-fetoprotein gene. Sequence organization and the 5' flanking region". Journal of Biological Chemistry. 260 (8): 5055–60. doi:10.1016/S0021-9258(18)89178-5. PMID 2580830.

- Ruoslahti E, Pihko H, Vaheri A, et al. (1975). "Alpha fetoprotein: structure and expression in man and inbred mouse strains under normal conditions and liver injury". Johns Hopkins Med. J. Suppl. 3: 249–55. PMID 4138095.

- Urano Y, Sakai M, Watanabe K, Tamaoki T (1985). "Tandem arrangement of the albumin and alpha-fetoprotein genes in the human genome". Gene. 32 (3): 255–61. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(84)90001-5. PMID 6085063.

- Beattie WG, Dugaiczyk A (1983). "Structure and evolution of human alpha-fetoprotein deduced from partial sequence of cloned cDNA". Gene. 20 (3): 415–22. doi:10.1016/0378-1119(82)90210-4. PMID 6187626.

- Morinaga T, Sakai M, Wegmann TG, Tamaoki T (1983). "Primary structures of human alpha-fetoprotein and its mRNA". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 80 (15): 4604–8. Bibcode:1983PNAS...80.4604M. doi:10.1073/pnas.80.15.4604. PMC 384092. PMID 6192439.

External links

edit- alpha-Fetoproteins at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- Overview of all the structural information available in the PDB for UniProt: P02771 (Alpha-fetoprotein) at the PDBe-KB.

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.