The Mariposa War (December 1850 – June 1851), also known as the Yosemite Indian War, was a conflict between the United States and the indigenous people of California's Sierra Nevada in the 1850s. The war was fought primarily in Mariposa County and surrounding areas, and was sparked by the discovery of gold in the region. As a result of the military expedition, the Mariposa Battalion became the first non-indigenous group to enter Yosemite Valley and the Nelder Grove.[1]

| Mariposa War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of California Genocide | |||||||

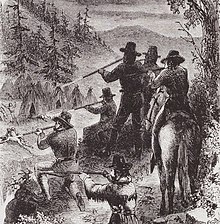

Members of the Mariposa Battalion firing into an indigenous people encampment during a campaign in the Mariposa War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Combatants | |||||||

| Mariposa Battalion |

Ahwahnechee Chowchilla | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| James D. Savage |

Tenaya Jose Juarez Jose Rey | ||||||

| Units involved | |||||||

|

Company A Company B Company C | Native Americans | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~200 militia | Unknown | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| Several killed and wounded | Unknown | ||||||

Location within California | |||||||

The war began in 1850 when miners entered the area of the Sierra Nevada foothills, which was traditionally occupied by the Ahwahnechee, a band of the Southern Sierra Miwok people. The miners began to take over the Ahwahnechee's land and resources, leading to tensions between the two groups.

The Ahwahnechee, led by their chief Tenaya, fought back against the miners resulting in a series of skirmishes that escalated into a full-scale war. The California state government, under Governor John McDougall, raised the Mariposa Battalion led by Sheriff James D. Savage to subdue the indigenous people.[2][3]

The war ended in 1851 with the capture of Tenaya and the surrender of his band. The Ahwahnechee were subsequently removed from the Sierra Nevada foothills and forced to live on reservations. The war resulted in the deaths of an unknown number of Ahwahnechee and several miners, and the displacement of the indigenous people from their ancestral lands.[4]

The Mariposa War was a part of the broader historical context of the California genocide and the American Indian Wars. Many European American settlers considered Native Americans to be an "Indian Problem" which they needed to remove.[4] The United States government, California state government, and White settlers enforced deliberate policies of displacement, forced removals, and massacres that drove Native Americans from their traditional lands and onto reservations.

Background

editThe California Gold Rush was the conflict that caused the California genocide.[4] By the end of May 1849, more than 40,000 gold seekers had used the California Trail to enter northern and central California which had been up until then populated by Native Americans and Californios (the descendants of early Spanish settlers). In two decades 80 percent of Californias Native American population was wiped out. Many California natives died from their land being seized by white settlers or the diseases brought from the new settlers, and about 9,000 from 16,000 were murdered. In three years, the non-Native American population rose from 14,000 in 1848 to 200,000 in 1852. Immigrants had come from Mexico, South America, Europe, Australia, and China.[4]

Miners digging for gold forced Native Americans off their historic lands. Others were pressed into service in the mines; others had their villages raided by the army and volunteer militia. White settlers also thought it was time to get rid of Native Americans due to the fact they thought took up too much labor in the mines.[4]

Mariposa County Sheriff James Burney and Savage led a militia of seventy four men in a retaliatory attack against a Chowchilla camp on the Fresno River near present-day Oakhurst on January 11, 1851. The militia attacked with rifles at daylight but were surprised when the Chowchilla returned fire with rifles and pistols of their own. Surprised and unprepared, Savage's forces staggered and dispersed, resulting in a victory for the Native Americans who killed several and wounded militia members in what would become known as the first battle of the Mariposa War.[5]

War

editMobilization

editSheriff James Burney made an appeal to John McDougal, the second Governor of California, which led to the creation of the Mariposa Battalion. The California State Militia that was a group of men who volunteered to form the Mariposa Battalion, sanctioned by the state of California, to rid the area of the perceived threat of Indians. They entered Yosemite Valley, systematically burned villages and food supplies and forced men, women, and children away from their homes. There were no native American homes left. [6] Under "Major" James D. Savage, at least one-fifth of the volunteers were Texans and had served previously under Colonel Jack Hays during the Mexican-American War. Its commands were:

- Company A : 70 men, led by Capt. John J. Kuykendall

- Company B : 72 men led by Capt. John Boling

- Company C : 56 men led by Capt. William Dill

Besides the military, officials from the Federal Indian commission sought a peaceful solution. On March 19, 1851, the Commissioners signed a treaty at Camp Fremont aside Mariposa Creek with six tribes. However, as the Ahwahneechees and Chowchillas were absent from the talks, a military campaign was launched against them the same day.

First campaign

editThe military action began when Company A — led by Captain Kuykendall — proceeded south to the Kings River and upper Kaweah Rivers and to the Tulare Valley. After arriving at the Kings River, scouts located a large Chowchilla village nearby. Company A charged into the Chowchilla camp, killing Native Americans. Some survivors were pursued, ridden down and taken prisoner. However, as Kuykendall's men had abandoned their horses for the village charge, many of the Chowchilla were able to escape on foot.

After the village attack, Kuykendall ordered his command to move onto the headwaters of the Kahweah River where they were unable to locate any more Chowchilla. A few days later, a group of Chowchilla entered their camp to sue for peace. The offer of peace was accepted and arrangements were made to transport the surviving Chowchilla to the reservation on the San Joaquin River. Following the transport, Kuykendall returned to the battalion's camp and headquarters on Mariposa Creek in early April.

Meanwhile, in their first campaign, the companies B and C of Boling and Dill had pursued Native Americans into the mountains where the units often forced to march through rain, sleet and deep snow drifts. on March 27, the companies discovered an Ahwahneechees Yosemite Valley refuge but few natives.

Second Campaign

editOn April 13, a new campaign against the Chowchilla was launched. Although units from the Mariposa Battalion destroyed the tribe's food stores, most Native Americans were able to elude the militias. However, with the death of their chief, the remaining Chowchilla surrendered and were transported onto a reservation.

Third Campaign

editAfter the Ahwahneechees refused to come to Camp Barbour, the Californian government launched a third campaign against them. The Mariposa Battalion encircled the Ahwahneechees at Lake Tenaija (named after Tenaya) on May 22. With little prospect of winning, the tribe acquiesced and surrendered Yosemite valley and the surrounding areas to the Californian government. The Battalion, acting as guards, marched the natives to the Fresno River Farm Reservation. After the Ahwahneechees were on the reservation, the militia returned to the Mariposa Creek post.

On July 1, 1852, the Mariposa Battalion was mustered out.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Eccleston, Robert (1957). C. Gregory Crampton (ed.). The Mariposa War, 1850–1851. University of Utah Press.

- ^ Beck, Warren A.; Hasse, Ynez D. "Mariposa Indian War". California State Military Museum. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "People". Yosemite National Park. National Park Service. January 14, 2023. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

The first non-native group to enter Yosemite was the Mariposa Battalion, a Euro-American militia formed to drive the native Ahwahneechee people onto reservations.

- ^ a b c d e "California's Little-Known Genocide". HISTORY. 2023-07-11.

- ^ Madera County Cemetery District (Grave marker plaque). Oakhill Cemetery, Oakhurst, California: Madera County Cemetery District and the Madera and Merced County Supervisors. 1970.

- ^ "Destruction and Disruption – Yosemite National Park (U.S. National Park Service)". www.nps.gov. Retrieved 2023-12-11.

Bibliography

edit- Bunnell, Lafayette Houghton (2003) [1880]. Discovery of the Yosemite and the Indian War of 1851 Which Led to That Event. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, National Digital Library Program. OCLC 51675913. Retrieved 2009-01-05.

- Cossley-Batt, Jill (1928). The Last of the California Rangers (First ed.). New York: Funk & Wagnalls Company. LCCN 28030766. OCLC 1600551.

- California and the Indian Wars: Mariposa Indian War, 1850–1851, by Warren A. Beck and Ynez D. Hasse

- Robert Eccleston. The Mariposa War, 1850–1851, C. Gregory Crampton, ed., Salt Lake City: University of Utah Press, 1957.

- California and the Indian Wars: The Mariposa War, By David A. Smith, Historian, The Burdick Military History Project, San Jose State University

- Map of the Mariposa War from Historical Atlas of California, published in 1975 by the University Of Oklahoma Press

- Reports from Lt. Tredwell Moore to the Pacific Division on the Mariposa Indian War of 1852.

- Mariposa History and Genealogy Research, A NOTE ON THE MARIPOSA INDIAN WAR, THE BATTLE OF HOGAN'S POTATO PATCH

- Events after the Mariposa Indian War, from Sam Ward in the Gold Rush (1861, 1949) by Samuel Ward