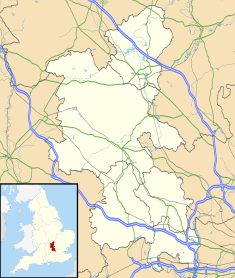

Marlow Town Hall is a municipal building in the Market Square, Marlow, Buckinghamshire, England. The structure, which was used as a public events venue, is a Grade II* listed building.[1]

| Marlow Town Hall | |

|---|---|

Marlow Town Hall | |

| Location | Market Square, Marlow |

| Coordinates | 51°34′19″N 0°46′38″W / 51.5719°N 0.7771°W |

| Built | 1807 |

| Architect | Samuel Wyatt |

| Architectural style(s) | Neoclassical style |

Listed Building – Grade II* | |

| Official name | Crown Hotel |

| Designated | 16 July 1949 |

| Reference no. | 1159570 |

History

editThe first municipal building in Marlow was a medieval market hall described as "a very old miserably heavy building of timber".[2] In the late 18th century the local member of parliament, Thomas Williams, offered to pay for the demolition of the old market hall and the erection of a more substantial building on the same site.[3] After Williams died in 1802, the initiative was implemented by Williams's son, Owen.[1]

The new building was designed by Samuel Wyatt in the neoclassical style, built by Benjamin Gray in coarse stone and was completed in 1807.[1][4] It was arcaded on the ground floor, so that markets could be held, with a large assembly room on the first floor.[3] The design involved a symmetrical main frontage with three bays facing onto the Market Square; on the first floor there were three sash windows with blind panels above flanked by Doric order pilasters supporting an entablature.[1] At roof level, there was a short central clock tower surmounted by a turret with a weather vane.[1] The clock was presented by Pascoe Grenfell who was elected to Williams's former seat at Westminster after he died;[3] manufactured by W. & J. Lawson of Newton-le-Willows, the clock struck the hours on the larger of the two bells in the turret (the other bell was used to raise the alarm in event of a fire).[5] A lock-up for petty criminals was established behind the left-hand arch.[3]

The town hall was attacked by rioters after Williams's grandson, Lieutenant General Owen Williams, who had used the town hall as his campaign headquarters, was elected the Conservative member of parliament in the 1880 general election.[6] In 1886, the Crown Hotel, which was located to the immediate northeast of the town hall, took over the management of the building and allowed the assembly room to remain available as a venue for public events.[3] A horse-drawn fire engine was installed in the area behind the left hand arch in the late 19th century.[3]

After significant population growth, largely associated with the status of Marlow as a market town, the area became an urban district in 1896.[7] Marlow Urban District Council chose not to meet at the town hall, but instead held its meetings at the Marlow Institute at 7 Institute Road, with administrative functions based at the firm of solicitors where the council's clerk worked at 41 High Street, just 200 yards (180 m) to the southeast of the town hall.[8][9] The council subsequently moved to Court Garden in 1934, which continues to serve as the offices and meeting place of its successor, Marlow Town Council.[10][11]

In the 1930s, the original Crown Hotel building was closed and the hotel moved permanently into the old town hall which was extended to the rear.[3] The assembly room continued to host major public events until the 1960s.[3][12] In the early 21st century, the Crown Hotel was rebranded "R Home", but it eventually closed in 2008,[13] and the building was subsequently converted for retail use.[14][15] Work was undertaken to refurbish the clock and to replace its mechanism:[16] the original mechanism was dismantled and initially discarded, but was later restored and placed on display in the foyer of the assembly room in 2013.[17]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e Historic England. "Crown Hotel (1159570)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Page, William (1925). "'Parishes: Great Marlow', in A History of the County of Buckingham". London: British History Online. pp. 65–77. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "The History of Marlow's Market House" (PDF). Marlow Society. 9 September 2006. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Pevsner, Elizabeth; Pevsner, Nikolaus (1994). Buckinghamshire (Buildings of England Series). Yale University Press. p. 68. ISBN 978-0300095845.

- ^ "Marlow Town Clock". Riley Park Trust. Retrieved 17 April 2023.

- ^ "The day the riots came to town". Bucks Free Press. 16 November 2005. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Marlow UD". Vision of Britain. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "No. 33940". The London Gazette. 16 May 1933. p. 3286.

- ^ Historic England. "41 and 41a, High Street (1332404)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ Historic England. "Court Garden (1125078)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Council minutes, 10 May 2022" (PDF). Marlow Town Council. Retrieved 31 May 2022.

- ^ "Public Halls". Kelly's Directory of Berkshire, Buckinghamshire and Oxfordshire. 1915. p. 329. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Farewell party for Marlow hotel". Bucks Free Press. 15 June 2008. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Steamer Trading Cookshop set to close in Marlow – but plans to relocate". Housewares Live. 25 January 2018. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "One Market Place, Marlow SL7 3HH" (PDF). Jackson Criss. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Town Tour". Marlow Society. Retrieved 12 August 2021.

- ^ "Two-hundred-year-old-clock to be restored by volunteers". Maidenhead Advertiser. 13 February 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2021.