The Matsieng Footprints are natural engravings found in southern Botswana. The site contains up to 117 engravings and three natural rock-holes,[1] dating back between 3,000 to 10,000 years.[2] Many of the footprints are human or feline-like in design.

| Matsieng Footprints | |

|---|---|

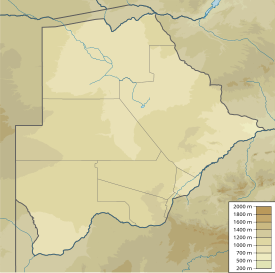

| Location | Botswana |

| Coordinates | 24°35′18″S 26°9′26″E / 24.58833°S 26.15722°E |

Archaeology

editMatsieng is a site in south east Botswana, near the city of Gaborone. It is known for its rock art, or petroglyphs, called the Matsieng Footprints. The site is littered with depressions, or holes, thought to have been formed as volcanic vents. They fill with rainwater, and are sometimes used by local peoples still today for water collection. There are two deeper cavities on the site; around the north east one is where most of the rock art is fogund.[3]

Most of the site is littered with carved footprints, both human and animal, but there are also a few profile depictions of common African animals, such as giraffes. The outlines of footprints were crafted by pecking, a form of engraving, by ancient peoples.[4] On the site, there is evidence of LSA dated artifacts, but it is more likely that the engravings were created earlier by hunter-gatherers, perhaps by ancestors of the San or the Basarwa.[3]

Matsieng is located on a flat outcrop of sandstone. The area was used as a watering hole for herders’ livestock and many of the petroglyphs suffered from the heavy foot traffic until recently. In 1918, study of the Matsieng footprints was conducted by Maria Wilman, who took rubbings of various petroglyphs onsite.[3] Human footprints on the site are distinguished by their shape, often u- or v-shaped heels with well-defined toes and an average length between 120-290 millimeters – excluding one larger footprint of 340 mm.[3] Footprints are rarely found in pairs, only a few are distinctly right or left feet; they create no clear trails to any destination and are often accompanied by big cat-like prints.[3]

Ideology

editThere are multiple origin stories about the creation of Matsieng. The legend of Matsieng is generally the same across many of the local people in the surrounding areas.[3] Oral tradition of the Tswana people depicts Matsieng as a one legged giant, who emerged from a waterhole with his animals. Other traditions depict Matsieng to be two legged, but the rest of the story is the same. He was followed by the San, the Kgalagadi and the Tswana tribes.[4]

As the giant and his followers emerged, they left footprints in the soft earth around the waterhole, which hardened over time.[3] Though there are several places that are thought to be the place of Matsieng's emergence, the archaeological site of Matsieng is most significant, given it holds that same name as the folklore character.

No one knows exactly what the Matsieng site was used for in the past, though many believe it served as a ceremonial site for ‘rain-making’.[4] Up until recently, the site was used by local peoples. They would bring their animals for a drink from the rainwater collecting holes. Today it is used as a ritual site, where local peoples conduct ceremonies to bring the seasonal rains.[4] Although no longer used as a watering hole, the petroglyphs were damaged by herding practices and are still battered by the elements.[3]

References

edit- ^ Chippindale, Christopher; Nash, George (2004). The Figured Landscapes of Rock-Art. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521524247.

- ^ "Matsieng Footprints". Botswana Tourism Organisation. Archived from the original on 25 July 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walker, Nick (1997). "In the Footsteps of the Ancestors: The Matsieng Creation Site in Botswana". South African Archaeological Bulletin. 52 (166): 95–104. doi:10.2307/3889074. JSTOR 3889074.

- ^ a b c d Van Der Ryst, Maria; Lombard, Marlize; Biemond, Wim (2004). "Rocks of Potency: Engravings and Cupules from the Dovedale Ward, Southern Tuli Block, Botswana". South African Archaeological Bulletin. 59: 1–11. doi:10.2307/3889317. JSTOR 3889317.