This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

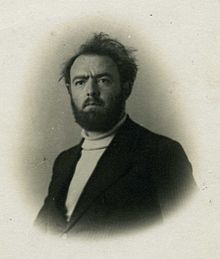

Matthijs Vermeulen (born Matheas Christianus Franciscus van der Meulen) (8 February 1888 – 26 July 1967), was a Dutch composer and music journalist.

Early life

editMatthijs Vermeulen was born in Helmond. After primary school he initially wanted to follow in the footsteps of his father, who was a blacksmith. During a serious illness his inclination towards the spiritual gained the upper hand. Inspired by a thoroughly Catholic environment, he decided to become a priest. However, at the seminary, where he learned about the principles of counterpoint of the sixteenth-century polyphonic masters, his true calling – music – came to light. On his eighteenth he abandoned his initial ideas and left school. In the spring of 1907 he moved to Amsterdam, the country's musical capital. There he approached Daniël de Lange, the director of the conservatory, who recognized his talent and gave him free lessons for two years. In 1909 Vermeulen began to write for the Catholic daily newspaper De Tijd, where he soon distinguished himself by a personal, resolute tone which stood out in stark contrast to the usually long-winded music journalism of the day. The quality of his reviews also struck Alphons Diepenbrock. He warmly recommended Vermeulen with the progressive weekly De Amsterdammer. There Vermeulen revealed himself as an advocate of the music of Claude Debussy, Gustav Mahler and Alphons Diepenbrock, whom he later used to call his "maître spirituel".

In the years 1912-1914 Vermeulen composed his actual opus 1, the First Symphony, which he called Symphonia carminum. In this work, expressing the joys of summer and youth, he already employed the technique he would remain loyal to for the rest of his life: polymelodicism. The four songs which Vermeulen wrote in 1917 display, each in its own special manner, the composer's preoccupation with war. In the reviews for 'De Telegraaf', a daily newspaper he worked for since 1915 as head of the Art and Literature department, he also showed just how much in his view politics and culture were inseparable.

Vermeulen's polemic against the unidirectional German orientation of Dutch musical life got him into trouble. After having presented his First Symphony to Willem Mengelberg, whom he much admired, he was disdainfully rejected after a one-year period of keen anticipation. Consequently, Vermeulen's orchestral work did not stand a chance in Amsterdam. The first performance, given by the Arnhem Orchestral Society in March 1919, took place under abominable circumstances and was a traumatic experience. Yet, Vermeulen started to work on his Second Symphony, Prélude à la nouvelle journée, shortly after that, and a year later he gave up journalism in order to fully dedicate himself to composing, while financially backed by some friends. After a last, fruitless appeal to Mengelberg, Vermeulen moved to France with his family in 1921 in the hope of finding a more favorable climate for his music. There he completed work on his Third Symphony Thrène et Péan, and composed the String Trio and the Violin Sonata.

However, Vermeulen's symphonic works did not find their way into the French concert halls either. From sheer necessity Vermeulen returned to journalism. In 1926 he became the Paris correspondent for the Soerabaiasch Handelsblad, a daily paper in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). For fourteen years he wrote two weekly extensive articles on every possible topic. The commission, in 1930, to compose the incidental music to the play De Vliegende Hollander [The flying Dutchman] by Martinus Nijhoff was encouraging. Nine years later he received a new impetus with the first performance of his Third Symphony by the Concertgebouw Orchestra conducted by Eduard van Beinum. The long-awaited confrontation with the resounding notes confirmed the effectiveness of his concepts. In the years 1940-1944 he composed his Fourth and Fifth Symphonies, bearing the titles of Les victoires and Les lendemains chantants, which symbolize Vermeulen's faith in the good outcome of World War II.

During the fall of 1944 Vermeulen had to take severe blows. In a short space of time he lost his wife and his most cherished son, who was killed while serving in the French liberation army. The diary Het enige hart [The singular heart] gives a deeply moving account of his mourning process. Seeking the meaning of this loss, Vermeulen drew up a philosophical construction, which he further developed in his book Het avontuur van den geest [The adventure of the mind].

In 1946 Vermeulen married Thea Diepenbrock, daughter of his former mentor, and went to work again for the weekly De Groene Amsterdammer, in the Netherlands. His articles on music rank among the most compelling in that area. In 1949 his Fourth and Fifth Symphonies were performed.

Politics and society kept on occupying Vermeulen passionately. He found the stifling atmosphere of the cold war increasingly depressing. Fearing a nuclear confrontation he spoke out against the arms race in several periodicals. During the first large-scale peace demonstration of 1955 he said: "The atomic bomb is an anti-life, anti-God, anti-man weapon."

The performance of the Second Symphony (which was awarded a prize at the 1953 Queen Elisabeth Music Competition in Brussels) during the 1956 Holland Festival instigated a new period of creativity. Vermeulen moved to rural Laren with his wife and child, where he composed the Sixth Symphony Les minutes heureuses, followed by various songs and the String Quartet. His last work, the Seventh Symphony, carrying the title Dithyrambes pour les temps à venir, reveals unflagging optimism. The composer died after a wasting disease, on 26 July 1967.

The 'Vermeulen Incident'

editVermeulen's dissatisfaction with the artistic policies of the Royal Concertgebouw Orchestra and its leader Willem Mengelberg came to a head in November 1918. After a performance of the Seventh Symphony of Cornelis Dopper, conducted by the composer, Vermeulen stood up and shouted Long live Sousa! from the stands of the Concertgebouw. A part of the audience thought that the socialist leader Troelstra, who had attempted a revolution days earlier, was meant and therefore interpreted Vermeulen's words as incitement, leading to great turmoil and a flurry of publications. The orchestra considered whether or not they could ban specific journalists from the hall. The incident also highlighted the already lumbering conflict between traditionalists (represented by Cornelis Dopper and chief conductor Willem Mengelberg) and avant-garde figures such as assistant conductor Evert Cornelis.

Even though the Concertgebouw's board would admit Vermeulen again after a while, his relations with the orchestra were tainted forever. As a consequence, Vermeulen's Second Symphony, written 1919–20 and entitled Prelude à la nouvelle journée, had to wait until the 1950s for its premiere; Mengelberg publicly stated that he would not even look at it (though see also this link [1]). As a result of numerous conflicts, Vermeulen decided to settle and work abroad for many years, particularly in France where he became a Paris correspondent for a journal in the then Dutch East Indies (Indonesia). He died in Laren.

Works

editHis symphonies, especially the last six of his seven, are atonal but also extremely contrapuntal, involving many musical lines combining simultaneously. In this he resembles Charles Ives in some ways. In his compositional work Vermeulen always focused his attention on melody. In his music a flow of melodies can be heard from beginning to end, quite diverse in form and character. The majority of the material is asymmetrical, based on the principle of 'free declamation', that is to say: the melodic curve and length of two consecutive sentences usually vary. Frequently Vermeulen spins long melismas into ever continuous melodies, in which every memory of period structure is absent. Particularly striking is the free rhythm of flowing lines, which have become disengaged from a fixed classification of metre by antimetric figures and ties. Yet elsewhere we come across short and pithy melodies, with a clear pulsation. A characteristic feature of his music is the sophisticated climactic activity and the alternation of tension and relief, mostly supported by harmony.

In his writings Vermeulen draws a parallel between melody and the individual: "The melody is a frame of mind expressed in tones." Seen in the light of Vermeulen's line of reasoning, a multi-voiced, polymelodic composition takes on the meaning of an aural representation of society. By combining several individual melodies, he reveals the wish he cherishes for society, namely that of every individual being able to freely express and develop himself, without infringing upon other people's freedom to develop their abilities. Although Vermeulen's writings on music give the impression that he was completely consistent in applying his polymelodic concept from the beginning until the end of a piece, most of his compositions contain several passages with only one or two voices, embedded in marvellous harmonies. Open, simple textures alternate with very complex ones, as does quasi-tonality with atonal constellations.

Early on, a spirit of freedom and urge for innovation prompted Vermeulen to abandon tonality and reject the traditional form schemes. In the First Cello Sonata free atonality breaks through in spurts, which from his Second Symphony onwards determines melody and harmony in his oeuvre. As opposed to Arnold Schoenberg, Vermeulen did not choose to build a new regulatory system, but proceeded purely in terms of thematic information and its logical and psychological development. His symphonies and chamber works consequently differ greatly as far as construction is concerned. But he always succeeded in creating architectonic cohesion. The Third Symphony is in a large A-B-A form, in which A develops linearly and B is reminiscent of a Classical rondo. The Fourth Symphony is built on six themes, three of which return just before the end; the long epilogue is counterbalanced by the hammering prologue, both on the pedal tone C. The large-scale Violin Sonata is based on the major seventh, omnipresent both in melody and harmony.

Vermeulen's compositions share a unique combination of energy, power, lyricism, and tenderness. The vitality of his works is the result of the aim he had in mind: to compose as an ode to the beauty of the earth and in astonishment about life, creating music which appeals to the spirituality of man, bestowing feelings of happiness on him and making him acquainted with the source of life, the Creative Spirit. These ambitions, put into words in the book titled Princiepen der Europese muziek (Principles of European music) and numerous articles, were at right angles to the mainstream movements. Consequently, Vermeulen did not have followers or disciples.

Apart from the aesthetic-ethical 'message', which is also the subject of most of his songs, Vermeulen's symphonies and chamber music offer an ingenious interplay of melodies, a colorful (orchestral) sound with many felicitous instrumental ideas, fascinating sound fields, innovating parallel harmony and a captivating canon technique.

Vermeulen's work has been quoted as seminal by influential Dutch composers such as Louis Andriessen, but his direct influence is much more difficult to trace - his style, after all, is eclectic and highly personal. Moreover, his actual collaboration with other composers remained very limited. Almost all of his recognition took place well after his death.

His works also include lieder with piano (one of these he orchestrated), chamber music including two cello sonatas, a string trio (1923)[1] and a string quartet, and incidental music for The Flying Dutchman.

Symphonies

edit- Symphony Nr. 1, Symphonia Carminum (1912–1914)

- Symphony Nr. 2, Prélude à la nouvelle journée (1920)

- Symphony Nr. 3, Thrène et Péan (1921)

- Symphony Nr. 4, Les Victoires (1941)

- Symphony Nr. 5, Les lendemains chantants (1945)

- Symphony Nr. 6, Les minutes heureuses (1958)

- Symphony Nr. 7, Dithyrambes pour les temps à venir (1965)

Other works

edit- On ne passe pas, for tenor and piano (1917)

- Les filles du roi d'Espagne, for mezzo-soprano and piano (1917)

- The soldier, for baritone and piano (1917)

- La veille, for mezzo-soprano and piano (1932: version with orchestra) (1917)

- Sonate pour violoncelle et piano (1918)

- Trio à cordes (string trio) (1923)

- Sonate pour piano et violon (1925)

- De Vliegende Hollander, for declamation, choir and orchestra (1930; 1950: for orchestra only)

- Deuxième sonate pour piano et violoncelle (1938)

- Trois salutations à notre dame, for mezzo-soprano and piano (1941)

- Le balcon, for mezzo-soprano or tenor and piano (1944)

- Préludes des origines, for bariton and piano (1959)

- Quatuor : pour 2 violons, alto et violoncelle (string quartet) (1961)

- Trois chants d'amour 1962 pour voix moyenne et piano (for mezzo-soprano and piano)

See also

editReferences and notes

editExternal links

edit- "official Vermeulen website". Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- "Further biography from publisher". Retrieved 2008-12-21.