Meridian is the eighth most populous city in the U.S. state of Mississippi,[2] with a population of 35,052 at the 2020 census.[3] It is the county seat of Lauderdale County and the principal city of the Meridian, Mississippi Micropolitan Statistical Area. Along major highways, the city is 93 mi (150 km) east of Jackson; 154 mi (248 km) southwest of Birmingham, Alabama; 202 mi (325 km) northeast of New Orleans, Louisiana; and 231 mi (372 km) southeast of Memphis, Tennessee.

Meridian, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

A view of downtown from the third floor of Meridian City Hall; the 16-story Threefoot Building dominates the skyline | |

| Nickname: Queen City | |

| Motto: "A Better Longitude On Life" | |

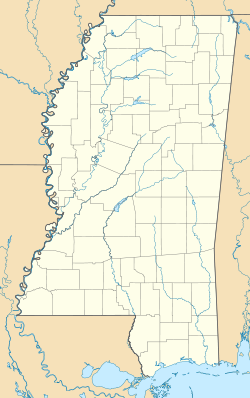

Location of Meridian in Lauderdale County | |

| Coordinates: 32°22′29″N 88°42′15″W / 32.37472°N 88.70417°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| County | Lauderdale |

| Incorporated | February 10, 1860 |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor-council government |

| • Mayor | Jimmie Smith (D) |

| Area | |

• City | 54.51 sq mi (141.17 km2) |

| • Land | 53.74 sq mi (139.19 km2) |

| • Water | 0.76 sq mi (1.98 km2) |

| Elevation | 344 ft (105 m) |

| Population (2020) | |

• City | 35,052 |

| • Density | 652.24/sq mi (251.83/km2) |

| • Metro | 107,449 |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (CST) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code(s) | 39301-39307 |

| Area code | 601 |

| FIPS code | 28-46640 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0673491 |

| Website | www |

Established in 1860, at the junction of the Mobile and Ohio Railroad and Southern Railway of Mississippi, Meridian built an economy based on the railways and goods transported on them, and it became a strategic trading center. During the Civil War, General William Tecumseh Sherman burned much of the city to the ground in the Battle of Meridian (February 1864). Rebuilt after the war, the city entered a "Golden Age". It became the largest city in Mississippi between 1890 and 1930, and a leading center for manufacturing in the South, with 44 trains arriving and departing daily. Union Station, built in 1906, is now a multi-modal center, with access to Amtrak and Greyhound Buses averaging 242,360 passengers per year. Although the economy slowed with the decline of the railroad industry, the city has diversified, with healthcare, military, and manufacturing employing the most people in 2010. The population within the city limits, according to 2008 census estimates, is 38,232, but a population of 232,900 in a 45-mile (72 km) radius and 526,500 in a 65-mile (105 km) radius, of which 104,600 and 234,200 people respectively are in the labor force, feeds the economy of the city.

The area is served by two military facilities, Naval Air Station Meridian and Key Field, which employ over 4,000 people. NAS Meridian is home to the Regional Counter-Drug Training Academy (RCTA) and the first local Department of Homeland Security in the state. Students in Training Air Wing ONE (Strike Flight Training) train in the T-45C Goshawk training jet. Key Field is named after brothers Fred and Al Key, who set a world endurance flight record in 1935. The field is now home to the 186th Air Refueling Wing of the Air National Guard and a support facility for the 185th Aviation Brigade of the Army National Guard. Rush Foundation Hospital is the largest non-military employer in the region, employing 2,610 people. Among the city's many arts organizations and historic buildings are the Riley Center, the Meridian Museum of Art, Meridian Little Theatre, and the Meridian Symphony Orchestra. Meridian was home to two Carnegie libraries, one for whites and one for African Americans. The Carnegie Branch Library, now demolished, was one of a number of Carnegie libraries built for blacks in the Southern United States during the segregation era.

The Mississippi Arts and Entertainment Experience (the MAX) is located in downtown Meridian. Jimmie Rodgers, the "Father of Country Music", was born in Meridian. Highland Park houses a museum which displays memorabilia of his life and career, as well as railroad equipment from the steam-engine era. The park is also home to the Highland Park Dentzel Carousel, a National Historic Landmark. It is the world's only two-row stationary Dentzel menagerie in existence.

Other notable natives include Miss America 1986 Susan Akin; James Chaney, an activist who was one of three civil rights workers murdered in 1964; singer Paul Davis; and Hartley Peavey, founder of Peavey Electronics headquartered in Meridian. The federal courthouse was the site of the 1966–1967 trial of suspects in the murder of Chaney and two other activists. For the first time, an all-white jury convicted a white official of a civil rights killing.[4]

History

editEarly History

editPreviously inhabited by the Choctaw Native Americans, the area now called Meridian was obtained by the United States under the terms of the Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek in 1830 during the period of Indian removal.[5] After the treaty was ratified, European-American settlers began to move into the area.

After receiving a federal land grant of about 2,000 acres (810 ha),[6] Richard McLemore, the first settler of Meridian,[5] began offering free land to newcomers to attract more settlers to the region and develop the area.[7] Most of McLemore's land was bought in 1853 by Lewis A. Ragsdale, a lawyer from Alabama. John T. Ball, a merchant from Kemper County, bought the remaining 80 acres (0.32 km2).[8] Ragsdale and Ball, now known as the founders of the city,[9] began laying out lots for new development on their respective land sections.[8]

There was much competition over the proposed name of the settlement. Ball and the more industrial residents of the city supported the name "Meridian," believing the term to be synonymous with "junction"; the more agrarian residents of the city preferred "Sowashee" (meaning "mad river" in Choctaw, from the name of a nearby creek); and Ragsdale proposed "Ragsdale City."[10][11] Ball erected a station house on the Mobile and Ohio Railroad – the sign on which would alternate between "Meridian" and "Sowashee" each day. Eventually the continued development of the railroads led to an influx of railroad workers who overruled the others in the city and left "Meridian" on the station permanently.[10] The town was officially incorporated as Meridian on February 10, 1860.[8]

Civil War and Reconstruction era

editAt the start of the American Civil War in 1861, Meridian was still a small village. But the Confederates made use of its strategic position at the railroad junction and constructed several military installations there to support the war.[8] During the Battle of Meridian in 1864, Union General William Tecumseh Sherman led troops into the city, destroying the railroads in every direction, as well as an arsenal and immense storehouses;[12] his forces burned many of the buildings to the ground.[13] Sherman is reported to have said afterwards, "Meridian, with its depots, store-houses, arsenal, hospitals, offices, hotels, and cantonments no longer exists."[13] Despite the destruction, workers rapidly repaired the railroad lines and they were back in operation 26 working days after the battle.[5]

Race relations were tense during the Reconstruction era, as whites resisted freedmen being allowed to choose their labor, vote, and have freedom of movement. Following a fire that damaged many businesses, the riot of 1871 erupted, with whites attacking blacks in the community. The black community had expanded after the war, as people moved to the city for more opportunity and to create community away from white supervision.

Golden Age and the Great Depression

editThe town boomed in the aftermath of the Civil War, and experienced its "Golden Age" from 1880 to 1910.[7] The railroads in the area provided for both passenger transportation and industrial needs, stimulating industry, businesses and a population boom.[7] Related commercial activity increased in the downtown area. Between 1890 and 1930, Meridian was the largest city in Mississippi and a leading center for manufacturing in the South.[5]

The wealth generated by this strong economy resulted in residents constructing many fine buildings, now preserved as historic structures, including the Grand Opera House in 1890,[14] the Wechsler School in 1894,[15] two Carnegie libraries in 1913,[16] and the Threefoot Building, Meridian's tallest skyscraper, in 1929.[17]

The city continued to grow thanks to a commission government's efforts to bring in 90 new industrial plants in 1913 and a booming automobile industry in the 1920s. Even through the stock market crash of 1929 and the following Great Depression, the city continued to attract new businesses. With escapism becoming popular in the culture during the depth of the Depression, the S. H. Kress & Co. building, built to "provide luxury to the common man,"[18] opened in downtown Meridian, as did the Temple Theater, which was first used as a movie house.[18] The federal courthouse was built in 1933 as a WPA project.[4]

After a brief slowdown of the economy at the end of the Depression, the country entered World War II, which renewed the importance of railroads. The rails were essential to transport gasoline and scrap metal to build military vehicles, so Meridian became the region's rail center again. This renewed prosperity continued until the 1950s, when the affordability of automobiles and the subsidized Interstate Highway System drew off passengers from the trains.[18] The decline of the railroad industry, which went through considerable restructuring among freight lines as well, caused significant job losses. The city's population declined as workers left for other areas.[7]

Civil Rights movement

editthe American Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, Meridian was home to a Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) office and several other activist organizations.[18] James Chaney and other local residents, along with Michael Schwerner, his wife Rita, and Andrew Goodman, volunteers from New York City, worked to create a community center. They held classes during Freedom Summer to help prepare African Americans in the area to prepare to regain their constitutional franchise, after having been excluded from politics since disenfranchisement in 1890.[19] Whites in the area resented the activism, and physically attacked civil rights workers.[20] In June 1964, Chaney, Schwerner, and Goodman went to Neshoba County, Mississippi, to meet with members of a black church that had been bombed and burned. The three disappeared that night on their way back to Meridian.[19] Following a massive FBI investigation, their murdered bodies were found two months later, buried in an earthen dam.

Seven Klansmen, including a deputy sheriff, were convicted by an all-white jury in the federal courthouse in Meridian of "depriving the victims of their civil rights".[4] Three defendants were acquitted in the trial for the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner.[21] This was the first time that a white jury had convicted "a white official in a civil rights killing."[4]

In 2005, the state brought charges in the case for the first time. Edgar Ray Killen was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to 60 years in prison.[22] Meridian later honored Chaney by renaming a portion of 49th Avenue after him and holding an annual memorial service.[23]

Modern history

editStarting in the 1960s and following the construction of highways that made commuting easier, residents began to move away from downtown in favor of new housing subdivisions to the north. After strip commercial interests began to move downtown, the city worked to designate several areas as historic districts in the 1970s and 80s to preserve the architectural character of the city.[7] The Meridian Historic Districts and Landmarks Commission was created in 1979, and the Meridian Main Street program was founded in 1985.[7]

Meridian Main Street organized several projects to revitalize downtown. This included construction of a new Amtrak Station in 1997, based on the design of the historic train station used during Meridian's Golden Age; it had been demolished.[24] Other projects included renovation of the Rosenbaum Building in 2001 and Weidmann's Restaurant in 2002, as well as support for integrated urban design.[25] Meridian Main Street, along with The Riley Foundation, helped renovate and adapt the historic Grand Opera House in 2006 for use as the "Mississippi State University Riley Center for Education and the Performing Arts."[25][26]

After ownership of the Meridian Main Street was transferred to the Alliance for Downtown Meridian in late 2007,[27] the two organizations, along with the Meridian Downtown Association, spearheaded the downtown revitalization effort.[28] The Alliance serves as an umbrella organization, allowing the other two organizations to use its support staff and housing, and in turn the Alliance serves as a liaison between the organizations.[28] Plans were underway to renovate the Threefoot Building, but newly elected Mayor Cheri Barry killed the plans in early 2010.[29] Today, the Alliance helps to promote further development and restoration downtown; its goal is to assist businesses such as specialty shops, restaurants, and bars because these help downtown become more active during the day and at night. The Meridian Downtown Association is primarily focused on increasing foot traffic downtown by organizing special events, and the Meridian Main Street program supports existing businesses downtown.[28]

Hotels

edit| Great Southern Hotel (1890) | Hotel Meridian (1907) |

| Union Hotel (1908) | Lamar Hotel (1927) |

Given Meridian's site as a railroad junction, its travelers have attracted the development of many hotels. Even before Meridian reached its "Golden Age," several large hotels, including the Great Southern and the Grand Avenue hotels, were built before the start of the 20th century.[30] With the growth of the railroads and the construction of the original Union Station in 1906, many hotels were constructed for passengers and workers.[18] The Elmira Hotel was constructed in 1905,[31] and the Terminal Hotel was constructed in 1910.[32] Hotel Meridian was constructed in 1907, and Union Hotel was built in 1908.[30] Union Hotel was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979,[33] and both Hotel Meridian and Grand Avenue Hotel were listed as contributing properties to the Meridian Urban Center Historic District.[18]

As the city grew, the hotels reflected ambitions of the strong economy, as evidenced by the 11-story skyscraper Lamar Hotel built in 1927.[30] Listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1979, the Lamar Hotel was adapted for use as a county annex building.[33] In 1988 it was listed as a Mississippi Landmark.[34] The E.F. Young Hotel was built in 1931.[35] A staple in the African-American business district that developed west of the city's core, the hotel was one of the only places in the city during the years of segregation where a traveling African American could find a room.[18]

As the city suburbs developed in the 1960s and '70s, most hotels moved outside of downtown. Rehabilitation of the Riley Center in 2006 has increased demand and a push for a new downtown hotel.[36][37] The Threefoot Building has been proposed for redevelopment for this purpose, but restoration efforts stalled with a change in city administrations.[38] The Threefoot Preservation Society was formed in 2013 to raise public awareness and support for the building's renovation, featuring tours of the first floor and anniversary events.

Historic districts

editMeridian has nine historic districts that are listed on the National Register of Historic Places. The Meridian Downtown Historic District is a combination of two older districts, the Meridian Urban Center Historic District and the Union Station Historic District. Many architectural styles are present in the districts, most from the late 19th and early 20th centuries, including Queen Anne, Colonial Revival, Italianate, Art Deco, Late Victorian, and bungalow. The districts are:[33][39]

1 East End Historic District – roughly bounded by 18th St, 11th Ave, 14th St, 14th Ave, 5th St, and 17th Ave.

2 Highlands Historic District – roughly bounded by 15th St, 34th Ave, 19th St, and 36th Ave.

3 Meridian Downtown Historic District – runs from the former Gulf, Mobile and Ohio Railroad north to 6th St between 18th and 26th Ave, excluding Ragsdale Survey Block 71.

- 4 Meridian Urban Center Historic District – roughly bounded by 21st and 25th Aves, 6th St, and the railroad.

- 5 Union Station Historic District – roughly bounded by 18th and 19th Aves, 5th St, and the railroad.

6 Merrehope Historic District – roughly bounded by 33rd Ave, 30th Ave, 14th St, and 8th St.

7 Mid-Town Historic District – roughly bounded by 23rd Ave, 15th St, 28th Ave, and 22nd St.

8 Poplar Springs Road Historic District – roughly bounded by 29th St, 23rd Ave, 22nd St, and 29th Ave.

9 West End Historic District – roughly bounded by 7th St, 28th Ave, Shearer's Branch, and 5th St.

Geography

editMeridian is located in the East Central Hills region of Mississippi in Lauderdale County. According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 54.50 square miles (141.2 km2), of which 53.74 square miles (139.2 km2) are land and 0.76 square miles (2.0 km2), or 1.40%, are water.[40] Along major highways, the city is 93 mi (150 km) east of Jackson, Mississippi; 154 mi (248 km) west of Birmingham, Alabama; 202 mi (325 km) northeast of New Orleans, Louisiana; 231 mi (372 km) southeast of Memphis, Tennessee; and 297 mi (478 km) west of Atlanta, Georgia.[41] The area surrounding the city is covered with oak and pine forests, and its topography consists of clay hills and the bottom lands of the head waters of the Chickasawhay River.[8]

The natural terrain of the area has been modified in the urban core of the city by grading, but maintains its gentle rolling character in the outlying areas. Numerous small creeks are found throughout the city, and small lakes and woodlands lie in the northern and southern portions of the city. Sowashee Creek runs through the southern portion of the city and is fed by Gallagher's Creek, which flows through the center of the city. Loper's Creek runs through the far-western part of the city, while smaller creeks including Shearer's Branch, Magnolia Creek, and Robbins Creek are dispersed throughout the city.[7]

Climate

editMeridian is in the humid subtropical climate zone. The average high temperature during summer (June through August) is around 90 °F (32 °C) and the average low is around 70 °F (21 °C). In winter (December through February) the average maximum is around 60 °F (16 °C) and minimum 35 °F (2 °C). The warmest month is July, with an average high of 92.9 °F (33.8 °C), and the coldest month of the year is January with an average low of 34.7 °F (1.5 °C).

The average annual precipitation in the city is 58.65 in (1,490 mm). Rainfall is fairly evenly distributed throughout the year, and the wettest month of the year is March, in which an average of 6.93 in (176 mm) of rain falls.[42] Much rainfall is delivered by thunderstorms which are common during the summer months but occur throughout the year. Severe thunderstorms – which can produce damaging winds and/or large hail in addition to the usual hazards of lightning and heavy rain – occasionally occur. These are most common during the spring months with a secondary peak during the fall months. These storms also bring the risk of tornadoes.

| Climate data for Meridian (Meridian Regional Airport), Mississippi (1991–2020 normals,[43] extremes 1889–present) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 83 (28) |

86 (30) |

93 (34) |

95 (35) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

107 (42) |

106 (41) |

105 (41) |

102 (39) |

89 (32) |

84 (29) |

107 (42) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 74.7 (23.7) |

78.3 (25.7) |

83.9 (28.8) |

87.0 (30.6) |

92.5 (33.6) |

95.7 (35.4) |

98.3 (36.8) |

98.1 (36.7) |

95.3 (35.2) |

89.8 (32.1) |

81.3 (27.4) |

76.2 (24.6) |

99.5 (37.5) |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 59.0 (15.0) |

63.8 (17.7) |

71.2 (21.8) |

78.2 (25.7) |

85.3 (29.6) |

91.0 (32.8) |

93.3 (34.1) |

93.1 (33.9) |

88.9 (31.6) |

79.5 (26.4) |

68.7 (20.4) |

61.1 (16.2) |

77.8 (25.4) |

| Daily mean °F (°C) | 47.7 (8.7) |

51.7 (10.9) |

58.5 (14.7) |

65.4 (18.6) |

73.3 (22.9) |

80.0 (26.7) |

82.7 (28.2) |

82.2 (27.9) |

77.3 (25.2) |

66.6 (19.2) |

55.8 (13.2) |

49.9 (9.9) |

65.9 (18.8) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 36.4 (2.4) |

39.7 (4.3) |

45.9 (7.7) |

52.6 (11.4) |

61.3 (16.3) |

68.9 (20.5) |

72.0 (22.2) |

71.3 (21.8) |

65.6 (18.7) |

53.7 (12.1) |

42.9 (6.1) |

38.6 (3.7) |

54.1 (12.3) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | 18.2 (−7.7) |

22.6 (−5.2) |

27.4 (−2.6) |

35.1 (1.7) |

45.3 (7.4) |

57.9 (14.4) |

64.1 (17.8) |

62.4 (16.9) |

50.5 (10.3) |

35.3 (1.8) |

26.3 (−3.2) |

22.6 (−5.2) |

16.0 (−8.9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 0 (−18) |

−6 (−21) |

15 (−9) |

28 (−2) |

38 (3) |

42 (6) |

54 (12) |

49 (9) |

34 (1) |

24 (−4) |

16 (−9) |

2 (−17) |

−6 (−21) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.61 (142) |

5.35 (136) |

5.66 (144) |

5.56 (141) |

4.20 (107) |

4.64 (118) |

5.11 (130) |

4.36 (111) |

3.17 (81) |

3.86 (98) |

4.21 (107) |

5.27 (134) |

57.00 (1,448) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 0.2 (0.51) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.3 (0.76) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.0 (0.0) |

0.1 (0.25) |

0.6 (1.5) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 in) | 9.9 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 8.7 | 9.1 | 10.7 | 11.9 | 9.9 | 7.0 | 6.8 | 8.3 | 10.4 | 113.1 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 in) | 0.2 | 0.1 | 0.1 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.0 | 0.1 | 0.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.4 | 71.1 | 69.4 | 70.4 | 73.1 | 73.9 | 76.7 | 76.7 | 76.3 | 74.7 | 74.8 | 74.8 | 73.9 |

| Source 1: NOAA[44][45] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (relative humidity 1961–1990)[46] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

edit| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1870 | 2,709 | — | |

| 1880 | 4,008 | 48.0% | |

| 1890 | 10,624 | 165.1% | |

| 1900 | 14,050 | 32.2% | |

| 1910 | 23,285 | 65.7% | |

| 1920 | 23,339 | 0.2% | |

| 1930 | 31,954 | 36.9% | |

| 1940 | 35,481 | 11.0% | |

| 1950 | 41,893 | 18.1% | |

| 1960 | 49,374 | 17.9% | |

| 1970 | 45,083 | −8.7% | |

| 1980 | 46,577 | 3.3% | |

| 1990 | 41,036 | −11.9% | |

| 2000 | 39,968 | −2.6% | |

| 2010 | 41,148 | 3.0% | |

| 2020 | 35,052 | −14.8% | |

| Source: US Census data | |||

2020 census

edit| Race | Num. | Perc. |

|---|---|---|

| White | 9,949 | 28.38% |

| Black or African American | 22,967 | 65.52% |

| Native American | 49 | 0.14% |

| Asian | 354 | 1.01% |

| Pacific Islander | 17 | 0.05% |

| Other/Mixed | 922 | 2.63% |

| Hispanic or Latino | 794 | 2.27% |

As of the 2020 United States Census, there were 35,052 people, 15,947 households, and 9,285 families residing in the city.

The city's growth has reflected the push and pull of many social and economic factors. The total population increased in each census from the city's founding until 1970, although varying from rates as high as 165% to as low as 0.2%. In the 1970 census the population decreased, then slightly increased by 1980, after which the population slowly declined, increasing again since the turn of the 21st century. Between 1980 and 2000, the population declined more than 14%.[48] As of the census of 2000, the city's population was 39,968, and the population density was 885.9 inhabitants per square mile (342.0/km2).[49] In 2008, the city was the sixth largest in the state.[50] The population increased as of 2010.

Meridian is the principal city in the Meridian micropolitan area, which as of 2009 consisted of three counties – Clarke, Kemper, and Lauderdale – and had a population of 106,139.[51] There is a population of 232,900 in a 45-mile (72 km) radius and 526,500 in a 65-mile (105 km) radius.[52]

While the overall population growth of the city has varied, there has been a steady growth in the number and percentage of non-white residents.[citation needed] The only decline in this group was between 1960 and 1970, when the city's overall population declined markedly. In the 2010 Census, the racial makeup of the city was 61.55% African American, 35.71% White, 0.9% Asian, 0.2% Native American, <0.02% Pacific Islander, 0.59% from other races, and 0.89% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.75% of the population.[49]

According to the 2000 Census, of the 17,890 housing units inside city limits, 15,966 were occupied, 10,033 of them by families. 31.1% of occupied households had children under the age of 18, 36.2% were married couples living together, 23.3% consisted of a female householder with no husband present, and 37.2% were non-families. 33.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 14.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.39 and the average family size was 3.06.[49] The average household size has steadily decreased since 1970, when it was 3.04. Meridian's median age has increased from 30.4 in 1970 to 34.6 in 2000.[48]

The median income for a household in the city was $25,085, and the median income for a family was $31,062. Males had a median income of $29,404 versus $19,702 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,255. About 24.6% of families and 28.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 40.8% of those under age 18 and 22.0% of those age 65 or over.[49]

Religion

editThe population of Meridian and its surrounds is fairly observant, with 65.2% of Lauderdale County affiliated with some type of religious congregation, compared to the national average of 50.2%.[53] Of the affiliated in 2000, 30,068 (59.0%) were in the Southern Baptist Convention, 9,469 (18.6%) were with the United Methodist Church, and 1,872 (3.7%) were associated with the Catholic Church.[53][54]

Immigrant Jews from Germany and eastern Europe were influential in commercial development of the city, building businesses and services.[55] Congregation Beth Israel was founded in 1868, just before the city's "Golden Age."[56] Meridian once had the largest Jewish community in the state, with 575 Jewish people living in the city in 1927.[55] Today, fewer than 40 Jews live in Meridian, most of whom are elderly.[57] Romani people also call Meridian home, including Kelly Mitchell, Queen of the Gipsy Nation, from whom the city may have derived the nickname "Queen City".[58][59]

Economy

edit| Employer | Industry type | Employees |

|---|---|---|

| NAS Meridian | Military | 3,000 |

| Rush Health Systems | Healthcare | 2,465 |

| Anderson Regional Health System | Healthcare | 1,343 |

| Mississippi Air National Guard | Military | 1,200 |

| Meridian Public School District | Education | 1,000 |

| East Mississippi State Hospital | Healthcare | 943 |

| Lauderdale County School District | Education | 938 |

| Walmart | Retail | 695 |

| City of Meridian | Government | 530 |

| iQor | Customer Service | 420 |

| Alliance Health Center | Healthcare | 350 |

| Meridian Community College | Education | 325 |

| Avery Dennison | Manufacturing | 250 |

| Peavey Electronics | Manufacturing | 250 |

| Van Zyverden, Inc. | Flower Bulb Distribution | 250 |

| Structural Steel Services | Manufacturing | 236 |

| Atlas Roofing | Manufacturing | 220 |

| Newell Paper | Wholesale | 215 |

| Lockheed Martin | Manufacturing | 200 |

| Tower Automotive | Automotive | 200 |

| Bimbo Bakeries USA | Food | 185 |

| Mitchell Distributing | Distribution | 120 |

| Magnolia Steel | Manufacturing | 107 |

| Southern Pipe and Supply | Distribution | 102 |

| Southern Cast Products | Manufacturing | 81 |

Early on, the economy depended greatly upon the railroads in the area. The city was the largest in Mississippi around the start of the 20th century, with five major rail lines and 44 trains coming in and out daily.[24] The city's economy not only depended on the rails but the goods, such as timber and cotton, transported on them. With these rail-based industries, the city was a great economic power in the state and region from about 1890 through 1930.[5] Though its economy slowed with the decline of the railroading industry in the 1950s,[7] the city has adapted, moving from a largely rail-based economy to a more diversified one, with healthcare, military, and manufacturing employing the most people.[52]

Along with Lauderdale County and the city of Marion, Meridian is served by the East Mississippi Business Development Corporation, which was formed in 1996 by a group of business leaders from the area.[60] While as of April 2010, the city's civilian labor force was only 15,420 people,[61] there is a population of 232,900 in a 45-mile (72 km) radius and 526,500 in a 65-mile (105 km) radius, of which 104,600 and 234,200 people respectively are in the labor force.[52] The city thus serves as a hub of employment, retail, health care, and culture activities.[62] Eighty percent of Lauderdale County's workers reside in the county while 90% live within 45 miles.[52]

In April 2020, there were 5,101 people employed in the healthcare field in Lauderdale County.[52] Rush Health Systems is the largest healthcare organization in the region, employing 2,465 people, followed by Anderson Regional Health System with 1,343 and East Mississippi State Hospital with 943.[52] There are two hospitals in Meridian, as well as many other healthcare-related facilities. Anderson Regional Medical Center provides cardiovascular surgery, a Level II newborn intensive-care unit, and a health and fitness center. In December 2010, Anderson bought Riley Hospital and absorbed its employees and stroke treatment center and rehabilitation services.[63] Rush Foundation Hospital and the related Rush Health Systems operate a Specialty Hospital of Meridian, which offers long-term care for non-permanent patients who require more recovery time in a hospital setting. Other healthcare facilities in Meridian include the Alliance Health Center and East Mississippi State Hospital, the latter of which has been in operation since 1882.[64]

Retail is another major employer in the county, with 5,280 people employed in April 2010.[61] Nearly $2 billion annually is spent on retail purchases in the city.[65] The 633,685-square-foot (58,871 m2) Uptown Meridian offers over one hundred shopping venues, including department stores, specialty shops, restaurants, eateries, and United Artists Theatres.[66] Phase I of the construction of Meridian Crossroads, a 375,000-square-foot (34,800 m2) shopping center in the Bonita Lakes area, was completed in November 2007, providing a major boost to retail in the area.[65] Also, the shopping district on North Hills Street has continued to expand, and in March 2007, additional retail and office space was opened near the Highway 19 Walmart Supercenter.[67]

The area is also served by two military facilities, Naval Air Station Meridian and Key Field, which supply over 4,000 jobs to residents of the surrounding area.[68] NAS Meridian provides training for naval carrier pilots and other enlisted personnel. Also housed at the base is the Regional Counter-Drug Training Academy (RCTA), which provides narcotics training for law enforcement in many southeastern states. Containing the first local Department of Homeland Security in the state, the city is the leader in a nine county regional response team and a twenty-nine county regional response task force.[69] Key Field is the site of the famous flight by brothers Fred and Al Key, who set a world endurance flight record in 1935.[70] Key Field is now home to the 186th Air Refueling Wing of the Air National Guard and a support facility for the 185th Aviation Brigade of the Army National Guard.[71] The site also contains an exhibit reviewing the history of aviation, and is the home of Meridian's Aviation Museum.[9]

The total manufacturing employment of Lauderdale County in April 2010 was 2,850 people.[61] Peavey Electronics Corporation, which has manufactured guitars, amplifiers, and sound equipment since 1965, operates its headquarters in the city. Other businesses in the area include Avery Dennison, Structural Steel Services, Bimbo Bakeries USA, Tower Automotive, and Teikuro Corporation. The city is also home to four industrial parks.[68]

In downtown, the MSU Riley Center provides revenue from tourism, arts, and entertainment sales.[72] The Riley Center attracts more than 60,000 visitors to downtown Meridian annually for conferences, meetings, and performances.[69] Loeb's Department Store on Front St has remained a Mississippi clothing landmark, having passed through four generations of family ownership. The store has been selling fine men's and women's clothing since 1887, when the store was first opened by Alex Loeb.[73]

Culture

editOne of the first art organizations in the city, The Meridian Art League, was established in February 1933. Art exhibitions were originally held in Lamar Hotel in downtown Meridian, but after a name change to Meridian Art Association in 1949, exhibitions were held at various locations around the city. After the Carnegie library at 25th Ave and 7th St was closed, the Art Association remodeled the building into the Meridian Museum of Art to serve as a permanent home for exhibits.[74] The museum was opened in 1970 and has since featured rotating exhibitions as well as many educational programs for both students and adults. Over thirty exhibitions are held annually, ranging from traditional decorative arts to ethnographic and tribal materials, photography, crafts, and many other works of art. The collection also includes 18th and 19th century portraits, 20th century photography, and several sculptures.[75]

The Meridian Council for the Arts (MCA) was founded as Meridian's and Lauderdale County's official arts agency in 1978. MCA operates its Community Art Grants program, the annual Threefoot Festival, several workshops, and other special events each year.[76] MCA is partnered with many arts organizations in the city and county including the Meridian Museum of Art, the Meridian Little Theatre, and the Meridian Symphony Orchestra.[77] Meridian Little Theatre, one of the South's oldest subscription-based community theatres, was built in 1932 and currently provides entertainment to residents of and visitors to Meridian and Lauderdale County, entertaining over 22,000 guests each season, making it Mississippi's most-attended community theatre.[78] The Meridian Symphony Orchestra (MSO) – founded in 1961 – played its first concert in 1962 and its first full season in 1963. In 1965 the MSO booked its first international soloist, Elena Nikolaidi, to perform with the orchestra. The Orchestra helped the Meridian Public School District develop its own orchestra and strings programs and also helped develop the Meridian Symphony Chorus. The current conductor is Dr. Claire Fox Hillard, who has been with the orchestra since 1991.[79] The MSO celebrated its 50th anniversary in February 2011 with a performance from Itzhak Perlman.[80]

The city's former Grand Opera House was built in 1889 by two half brothers, Israel Marks and Levi Rothenberg. During its operation the opera house hosted many famous artists and works, the first being a German company's rendition of Johann Strauss II's "The Gypsy Baron".[81][82] After closing in the late 1920s due to the Great Depression, the opera house was abandoned for nearly 70 years. A $10 million grant in 2000 by the Riley Foundation, a local foundation chartered in 1998, sparked the building's restoration while $15 million came from a combination of city, county, and federal grants.[81] The opera house's renovation was completed in September 2006 under the new name "Mississippi State University Riley Center for Education and Performing Arts." The Riley Center, which includes a 950-seat auditorium for live performances, a 200-seat studio theater, and 30,000 sq ft (2,787 m2) of meeting space,[83] attracts more than 60,000 visitors to downtown Meridian annually for conferences, meetings, and performances.[69]

Meridian is considered an architectural treasure trove being one of the USA's most intact cities from the end of the nineteenth and start of the twentieth centuries. Architecture students from around the nation and Canada are known to visit Meridian in groups as part of their coursework due to numerous structures in the city having been designed by noted architects. The only home in the US south designed by noted Canadian born architect Louis S. Curtiss, famous for inventing the glass curtain wall skyscraper, is extant on Highland Park. The Frank Fort-designed Threefoot Building is generally considered one of the best Art Deco skyscrapers in the US and is often compared to Detroit's famed Fisher Building. Noted California architect Wallace Neff designed a number of homes in Meridian as well as in the Alabama Black Belt which adjoins the city across the nearby Alabama State line. He had relatives in Meridian and Selma who were executives in the then thriving railroad industry and would take commissions in the area when commissions in California were lean. His work is mostly concentrated in the lower numbered blocks of Poplar Springs Drive where his 2516 Poplar Springs Drive is often compared to the similarly designed Falcon Lair, the Beverly Hills home in Benedict Canyon of Rudolph Valentino. One Neff work was lost to an expansion of Anderson Hospital in 1990 and another in Marion Park burned in the 1950s. The Meridian Post Office with its interior done entirely of bronze and Verde marble is also noteworthy as a very fine example of the type of post office built in thriving and well to do cities in the 1920s and originally had Lalique lighting which was removed during a 1960s remodeling, and which are now in private residences on Poplar Springs Drive and in North Hills.

Meridian has been selected as the future location of the Mississippi Arts and Entertainment Center (MAEC). The Mississippi Legislature approved the idea in 2001[84] and in 2006 promised $4 million in funding if private contributors could raise $8 million.[85] The city donated $50,000 to the cause in September 2007.[86] The MAEC, as proposed, would be located on 175 acres (71 ha) at Bonita Lakes and consist of an outdoor amphitheatre, an indoor concert hall, and a Hall of Fame honoring Mississippi artists.[9] The Hall of Fame will be located downtown in the old Montana's building. That property and the adjacent Meridian Hotel building were acquired in July 2010 for $300,000.[87] In February 2009, the MAEC revealed its Walk of Fame outside of the Riley Center in an attempt to promote the planned Hall of Fame. The first star on the walk was dedicated to Jimmie Rodgers, a Meridian native.[88] In September of the same year, the second star was revealed, recognizing B.B. King, a famous blues musician from Mississippi.[89] On June 1, 2010, authors Tennessee Williams, Eudora Welty, and William Faulkner were added to the walk.[90] Sela Ward was added to the walk on June 24, 2010.[91] The MAEC plans to add many more Mississippi-born stars to the Walk of Fame; names mentioned include Morgan Freeman, Jimmy Buffett, Elvis Presley, Conway Twitty, and others.[89]

Another location in the city used for large productions is the Hamasa Shrine Temple Theater. The Temple Theater houses a 778-pipe Robert Morgan organ, one of two Theater Organs still in their original installations in the state.[92] With seating for 1800 persons, the silent movie era was a prosperous time for the Temple. At the time, it was one of the largest stages in the United States, second only to the Roxy Theater in New York City.[93] Today, seating 1576 persons, the Temple is used year-round for area events, live stage shows, plays, concerts, Hamasa Shrine functions, and public screenings of classic movies.[94]

Highland Park houses a Jimmie Rodgers museum which displays the original guitar of "The Singing Brakeman" and other memorabilia of his life and career, as well as railroad equipment from the steam-engine era. In addition to the museum building itself, there are outside memorials, and a vintage steam locomotive on display.[95] A Mississippi Blues Trail historic marker has been placed in Meridian to honor the city as the birthplace of Jimmie Rodgers and emphasizes his importance to the development of the blues style of music in Mississippi. The city was the first site to receive this designation outside the Mississippi Delta.[96] Also, a Mississippi Country Music Trail marker was placed in Oak Grove Cemetery in honor of Rodgers on June 1, 2010.[97] Each year since 1953, the city has held a festival during May to honor the anniversary of his death.[98]

The park is home to a 19th-century carousel manufactured around 1895 by Gustav Dentzel of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Highland Park Dentzel Carousel has been in operation since 1909, is a National Historic Landmark, and is the world's only two-row stationary Dentzel menagerie in existence. Its house is the only remaining original carousel building built from a Dentzel blueprint.[99] Around Town Carousels Abound is a public arts project of 62 carousel horses, representing the historic carousel. Sixty-two pieces have been sponsored by local businesses and citizens, and design of the horses was conceived and painted by local artists. They are placed throughout the city and county.[100]

Recreation

editThe city contains several recreational parks, including Highland Park, Bonita Lakes, and Okatibbee Lake. Highland Park contains picnic shelters, swimming pools, tennis courts, a baseball field, softball fields, and a playground,[101] all open year-round to visitors.[9] Bonita Lakes is a city-owned, 3,300-acre (13 km2) park including three lakes. The park also includes the Long Creek Reservoir and Lakeview Municipal Golf Course, along with nature trails, a jogging and walking track, biking paths, horseback riding trails, pavilions, picnic facilities, boat ramps, paddle boats, concessions, and fishing.[102] Along with the lakes, the Bonita Lakes area includes Uptown Meridian, Bonita Lakes Crossing, and Bonita Lakes Plaza.[66] Okatibbee Lake is a 7,150-acre (28.9 km2) establishment containing a 4,144-acre (16.77 km2) lake which offers boating, fishing, swimming, water skiing, picnicking, hunting, hiking and camping.[103] Splashdown Country Water Park, a 25-room motel, and cabins are located on the lake.[102]

Since 1992, Meridian has been a host of the State Games of Mississippi, a statewide annual multi-sport event modeled after the Olympic Games.[104] The organization is a member of the National Congress of State Games, which is affiliated with the U.S. Olympic Committee.[105] In its first year 1,200 athletes competed in twelve sports, and since then over 70,000 athletes have participated in the Games. In 2009, more than 4500 athletes participated in 27 sports.[104] All competitors in the games can compete in the Southeast Sports Festival, while medalists may move up to the bi-annual State Games of America.[105]

Originally the games were held in one weekend in June, but as more sports were added, the event was expanded to two weekends.[106] Opening ceremonies always begin on the third Friday in June in downtown Meridian.[104] The games are held at several sports parks, including Northeast Park, Sammie Davidson Complex, and other various fields throughout the city. Northeast Park is an 85-acre (34 ha) park on Highway 39 that contains 10 tennis courts, four softball fields, three soccer fields, an asphalt track, and a large picnic pavilion.[107] The Sammie Davidson Sports Complex includes six tennis courts, four softball fields, and a half-mile track. Other sports fields include the Meridian Jaycee Soccer Complex, Sykes Park, and Phil Hardin Park.[108]

There are several golf courses in the city, including the aforementioned Lakeview Municipal Golf Course, an 18-hole course open to the public daily.[102] Briarwood County Club, located on Highway 39 North, is a private club with golf, swimming, fishing, and dining facilities.[109] Other golf courses serving the city include Northwood Country Club, Okatibbee Creek Golf Center, and Ponta Creek Golf Course.[102]

Government and infrastructure

editMeridian has operated under the mayor-council or "strong mayor" form of government since 1985.[110] A mayor is elected every four years by the population at-large. The five members of the city council are elected every four years from each of the city's five wards, considered single-member districts. The mayor, the chief executive officer of the city, is responsible for administering and leading the day-to-day operations of city government. The city council is the legislative arm of the government, setting policy and annually adopting the city's operating budget.[111]

City Hall, which has been listed on the National Register of Historic Places,[33] is located at 601 23rd Avenue. The current mayor is Jimmie Smith. Members of the city council include Dr. George M. Thomas, representative from Ward 1, Dwayne Davis, representative from Ward 2, Joseph Norwood, representative from Ward 3, Romande Gail Walker, representative from Ward 4, and Tyeasha "Ty" Bell Lindsey, representative from Ward 5. The council clerk is Jo Ann Clark.[111] In total, the city employs 570 people.[52]

The city has a Department of Homeland Security (DHS), becoming the only local DHS in the state. The team oversees an area of nine counties. Upon receiving $2.5 million in grants from the Mississippi Emergency Management Agency and other organizations, the department began training law enforcement offices from other Southern states in passenger rail rescue as well as offering civilian classes in basic handguns, Boy Scout first aid and hunting, and firearms training. The DHS helps during times of crisis such as Hurricane Ivan in September 2004, when the department helped establish and support shelters for 700 evacuees.[112] The city now serves as the leader of one of the task forces in the Mississippi DHS, a combination of three nine-county teams.[113]

Headed by police chief Lee Shelbourn since 2009, the Meridian Police Department consists of 115 full-time officers as well as part-time and reserve staff available.[114] In 2009, the department's Criminal Investigations Division responded to 4000 cases, 2000 of which were felonies.[113] In 2000, 2094 crimes were reported, up slightly from 2008 crimes the preceding year. Meridian has been described as "the safest city in Mississippi with more than 30,000 people."[115] The East Mississippi Correctional Facility is located in unincorporated Lauderdale County, near Meridian. It is operated by the GEO Group on behalf of the Mississippi Department of Corrections.[116] The chief of the Meridian Fire Department is Anthony Clayton.[117] The fire department responded to more than 1600 calls in 2009, including 123 structural fires and 609 emergency service calls.[113] The Mississippi Department of Mental Health operates the East Mississippi State Hospital in Meridian.[118][119][120] The United States Postal Service operates the Meridian,[121] North Meridian,[122] and the West Meridian Station post offices.[123]

In state politics, the Mississippi Senate district map divides the city into three sections.[124] The northern tip of the city is in the 31st State Senate District and seats Terry Clark Burton (Republican party). A strip of the city from the southwest corner up to the northeast corner comprises part of the 32nd State Senate District and seats Sampson Jackson, II (Democratic party). The western and southeastern portions of the city lie in the 33rd State Senate District and seats Videt Carmichael (Republican party).[125] In the Mississippi House of Representatives districts, the city is divided into four districts.[126] The southern and eastern portions of the city reside in House District 81 and are represented by Steven A. Horne (Republican party). The city's core makes up the entirety of House District 82 and is represented by Wilbert L. Jones (Democratic party). Surrounding House District 82 is House District 83, represented by Greg Snowden (Republican party). The western section of the city, along with a small section in the north, lie in House District 84 and are represented by Tad Campbell (Republican party).[127]

On the national level, the city is located in Mississippi's 3rd congressional district, represented by Gregg Harper (Republican party), who has been in office since 2009. Lauderdale County, home to Meridian, has voted for the Republican candidate in every United States presidential election since 1972. Before the shift to the Republican Party, white area voters supported Democratic Party candidates, as for decades since the late 19th century, it was a one-party state.[128]

Transportation

editRailroads and public transit

editAmtrak's Crescent train connects Meridian with the cities of New York, New York; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania; Baltimore, Maryland; Washington, D.C.; Charlotte, North Carolina; Atlanta, Georgia; Birmingham, Alabama; and New Orleans, Louisiana. The Union Station Multi-Modal Transportation Center (MMTC) is located at 1901 Front Street, part of the Meridian Downtown Historic District, which is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Originally built in 1906, but later demolished in 1966 then rebuilt in 1997, the station includes several modes of transportation including Amtrak, Norfolk Southern rail corridor, Greyhound buses, Trailways and other providers of transit services. The number of passengers on Amtrak trains, Greyhound buses, and Meridian Transit System buses averages 242,360 per year.[129] The Meridian Transit System ceased operations in 2012 due to lack of funding support for local match by the mayoral administration.

Air

editThe city is served by Meridian Regional Airport, located at Key Field, 2811 Airport Boulevard South, 3 mi (4.8 km) southwest of the city. At 10,004 foot (3,049 m), the airport's runway is the longest public runway in Mississippi. The airport, which has been in service since 1930, offers daily flights to Dallas/Fort Worth.[130]

During the Great Depression, residents of the city contemplated abandoning the airport because of the cost of maintenance, but in 1935 Brothers Fred and Al Key, managers of the airport, thought of a way to keep the airport operating. From June 4 until July 1, 1935, the brothers flew over the city in their plane, the "Ole Miss." The record they established in their 27 days aloft, totaling 653 hours and 34 minutes, attracted enough publicity and funds to the city to keep the airport running. Key Field is therefore named after the brothers, whose flight endurance record remains unbroken in conventional flight.[131]

Highways

edit- Interstate highways

Interstate 20

Runs west through Jackson, Mississippi, eventually terminating near Kent, Texas, and east through Tuscaloosa, Alabama, eventually terminating in Florence, South Carolina.

Interstate 59

Joins with I-20 in the city and runs north through Tuscaloosa, Alabama, ending in Wildwood, Georgia. It also runs south through Hattiesburg, Mississippi, and on to Slidell, Louisiana.

- U.S. highways

U.S. Highway 11

Runs parallel to Interstate 59 south to New Orleans, Louisiana, and north all the way to the Canada–U.S. border.

U.S. Highway 45

Transnational route which runs north through Columbus, Mississippi, to the U.S.-Canada border and south through Quitman, Mississippi, to Mobile, Alabama, and the Gulf of Mexico.

U.S. Highway 80

Runs west through Jackson, Mississippi, to Dallas, Texas, and east through Demopolis, Alabama, all the way to Tybee Island, Georgia and the Atlantic Ocean.

- State highways

Mississippi Highway 19

Runs north to West, Mississippi, and south to the Mississippi-Alabama border, where it continues as Alabama State Route 10.

Mississippi Highway 39

Begins in Meridian and runs north to Shuqualak, Mississippi.

Mississippi Highway 145

Formerly US 45, but now only exists as an alternate route in several cities.

Mississippi Highway 493

Begins in Meridian and runs north to Lynville, Mississippi.

Education

editEarly public education in Meridian was based on the 1870 Mississippi Constitution. From 1870 to 1885, trustees appointed by the City Council served on the Board of School Directors, which had authority to operate the schools.[132] Although there were several schools in the city before 1884, they were privately owned and only enrolled about 400 students. The city did not build its first publicly owned school until September 1884.[133] The first public school for blacks in the city was held in facilities rented from St. Paul Methodist Church. The Mississippi Legislature amended the city charter in January 1888 to allow the city to maintain its own municipal school district, and in March of the same year $30,000 in bonds was approved for the city to build new public schools.[132] From this bond, the Wechsler School was built in 1894, becoming the first brick public school building in the state built for blacks.[132]

From this early district and later additions, the Meridian Public School District grew to its current size, which now includes six elementary schools,[134] three middle schools,[135] and three high schools.[136] The city also contains several private schools, including Lamar School, Community Christian School, and St. Patrick's Catholic School.[137] The campus of Meridian High School, the main high school in the district, occupies 37 acres (15 ha), including six buildings and 111 classrooms. The school is made up of grades 9–12 and enrolls approximately 1,500 students.[138]

Meridian is home to two post-secondary educational institutions. Meridian Community College, founded in 1937, is located at 910 Highway 19 N and offers free tuition for four semesters to graduates from the Meridian Public and Lauderdale County School Districts as well as homeschooled children who reside inside Lauderdale County.[139] Originally known as Meridian Junior College and located at Meridian High School, the college moved to its present location in 1965. After desegregation laws were passed, MJC merged with T.J. Harris Junior College in 1970, which had previously enrolled African-American students. The name change from Meridian Junior College to Meridian Community College took place in 1987 "to more accurately reflect the diversity of opportunities it provides for a growing community area."[140] Mississippi State University also operates a campus in the city. As of the Fall 2008 semester, 763 students from 33 counties throughout the state and several in Alabama attended the college.[141]

Meridian is served by the Meridian-Lauderdale County Public Library, located at the corner of 7th Street and 26th Avenue. The city originally had two Carnegie libraries, both built in 1913 – one for blacks and one for whites. A group of women had formed the Fortnightly Book and Magazine Club in the 1880s and began raising money to build a library for the city. The books they collected and shared within the club were later the basis of the library collection for Meridian. With wide support for the library, the club enlisted Israel Marks, a city leader, to approach the national philanthropist Andrew Carnegie for funding assistance.[142] The library for blacks was built at 13th Street and 28th Avenue on land donated by St. Paul Methodist Church, and the library for whites was established in a building originally owned by members of the First Presbyterian Church of Meridian, who sold it to the city on September 25, 1911.[143] The African American library was the only library for blacks in the state until after World War I[144] and is the only Carnegie library ever built for African Americans in the country.[145] The two libraries served the city until 1967, when the institutions became integrated because of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, combined their collections, and moved all materials to their current location.[146] The former white library was renovated and converted into the Meridian Museum of Art in 1970, and the former African-American library was demolished on May 28, 2008.[147]

Media

editThe only daily newspaper printed in the city is The Meridian Star,[148] which has been in operation since 1898.[149] The paper was originally named The Evening Star but was renamed in 1915 and has been Meridian's only daily newspaper since 1921. With a daily circulation of about 12,000 in March 2010,[150] the paper serves Lauderdale County as well as adjacent portions of western Alabama and eastern Mississippi.

Although the Meridian Star is now the only newspaper printed in the city, there have been a few other historical newspapers. One such paper is the Memo Digest, a ten to twenty page publication published during the 1970s. The Digest focused on issues relevant to the African-American population of the region, gathering a circulation of about 5,000 people.[151] Other newspapers in the city have included The Colored Messenger,[152] The State,[153] The Weekly Mercury,[154] The Blade, Weekly Echo, Fair Play, Headlight, Meridian Morning Sun, Teacher and Preacher, and Clarion.[151]

The city is the principal city in the Meridian, Mississippi Designated Market Area (DMA), which includes 72,180 households with televisions.[155] WTOK-TV broadcasts as an ABC affiliate from the city, headquartered at 815 23rd Avenue.[156] WTOK operates two digital subchannels, WTOK-DT2, a MyNetworkTV affiliate, and WTOK-DT3, Meridian's CW.[157] WMDN-TV is the market's CBS affiliate. WGBC-TV is the affiliate network carrying both FOX (WGBC-DT1) and NBC (WGBC-DT2) programming. Both stations share studios and transmitter facilities on Crestview Circle in unincorporated Lauderdale County, south of Meridian. Together, WGBC and WMDN are known as "The Meridian Family of Stations."[158] WMAW-TV is the local affiliate of Mississippi Public Broadcasting.[159]

The city is also the principal city in the Meridian Arbitron Radio Market, which includes 64,500 people over the age of 12.[160] WUCL (FM 105.7), headquartered at 3436 Highway 45 North,[161] takes the largest share of ratings in the market at 14.8% in Fall 2009. In the same period, WZKS (FM 104.1) was second with 11.1%, and WMOX (AM 1010) was third with 7.4%.[162] Other popular stations in the market include WKZB (FM 97.9), WOKK (FM 97.1), WEXR (FM 106.9), WYHL (AM 1450), and WJXM (FM 95.1).[162] Mississippi Public Broadcasting can be found on WMAW-FM (FM 88.1).[159]

Notable people

edit- John Luther Adams, composer; although more associated with Alaska, he was born in Meridian

- Susan Akin, who won the Miss America beauty pageant in 1986[163]

- John Alexander, opera singer

- Moe Bandy, country music singer

- John Besh, New Orleans cuisine chef, TV personality, philanthropist, restaurateur and author[164]

- Big K.R.I.T., musician

- Dennis Ray "Oil Can" Boyd, former Major League Baseball pitcher[165]

- Gil Carmichael, Meridian businessman, transportation specialist, and politician, was the Republican nominee for the Mississippi Senate in 1966 and 1967, U.S. Senate in 1972, governor in 1975 and 1979, and lieutenant governor in 1983[166]

- Brad Carter, engineer, Mississippi State Senator (1996–2000), owner of WMER[167]

- James Chaney, one of the victims in the murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner in 1964[168]

- Alvin Childress, actor, played the lead role on the Amos 'n' Andy Show[169]

- Austin Davis, NFL player

- Paul Davis, singer-songwriter best known for the late 1970s and early 1980s pop hits "I Go Crazy" and "'65 Love Affair", was born in Meridian in 1948; after retiring, he returned to the city where he remained until his death in 2008[170]

- Winfield Dunn, former Governor of Tennessee, lived in Meridian[171]

- Cordera Eason, NFL player

- John Fleming, U.S. Representative for Louisiana's 4th congressional district 2009–2017, was born and raised in Meridian[172]

- Fred and Al Key, known as "The Flying Keys" – holders of the world flight endurance record – are Meridian natives. Al Key is also a former mayor of the city.[173]

- Steve Forbert, folk singer best known for "Romeo's Tune"

- Paul Hardy, Negro leagues catcher[174]

- Ty Herndon, country music singer

- Rodney Hood, professional basketball player

- Pooley Hubert, college football player & coach

- Leroy Jones, former professional boxer

- Gregory Keyes, science fiction and fantasy writer[175]

- Diane Ladd, actress, actually born in Laurel, but raised in Meridian, where her parents resided[176][177]

- Lilian Lewis, zoologist.[178]

- Alex M. Loeb, artist[179]

- Derrick McKey, NBA player[180]

- Scott McQuaig, country singer and recording artist

- Kelly Mitchell, Queen of the Gypsy Nation[58]

- Gillespie V. Montgomery, former U.S. Representative, lived in Meridian[181]

- Montez Murphy, former NFL defensive tackle

- Hartley Peavey, founder of Peavey Electronics, which is headquartered in Meridian[182]

- Fred Phelps, former (now deceased) leader of the Westboro Baptist Church[183][184]

- Robert Pious (1908–1983), American painter and illustrator[185]

- Jay Powell, pitcher

- David Charles Richardson, commander and vice admiral in the United States Navy[186]

- Jimmie Rodgers, the "Father of Country Music", was born in the city in 1897. The Jimmie Rodgers Museum is located in Meridian, and the Jimmie Rodgers Festival has been an annual Meridian event since 1953.[187]

- David Ruffin, former lead singer of The Temptations, and his older brother Jimmy Ruffin were born in the surrounding area, Whynot and Collinsville, respectively.[188][189]

- Julian Rush (1936-2023), clergyman, playwright, and non-profit administrator[190]

- Joe Stringfellow, NFL player[191]

- Pat Sansone, Guitarist from Wilco

- Anne Mollegen Smith, magazine editor and writer[192]

- Elliott Street, Actor and writer[193] Former Executive Director, Grand Opera House Revitalization Project, Meridian, MS., Teaching and Touring Artist - Retired Theatre and Speech Instructor, Meridian Community College, Served as curator of the historic Meridian Opera House

- Tom Stuart, politician, from 1973 to 1977 was the first Republican to serve as mayor of Meridian in the 20th century[194]

- Joni Taylor, Texas A&M Aggies women's basketball coach

- Todd Tilghman, singer and lead pastor of Cornerstone Church in Meridian. A winner of 18th season of The Voice.

- Mary Oneida Toups, occultist known as the "Witch Queen of New Orleans"

- Alejandro Villanueva, NFL player

- Kenyatta Walker, All-American collegiate football player; Super Bowl XXXVII champion as a member of the Tampa Bay Buccaneers

- Lillian W. Walker, member of the Louisiana House of Representatives for East Baton Rouge Parish from 1964 to 1972[195]

- Sela Ward, actress[196]

- Brad Watson, writer

- James Wheaton, actor and director

- Hayley Williams, lead singer of the band Paramore[197]

- Al Wilson, singer

- George Wilson – former NBA center (1964–71)[198][199][200]

- John Louis Wilson Jr. (1898–1989), American architect[201]

- Charles Young Jr., business executive and current member of the Mississippi House of Representatives

- Charles L. Young Sr., business executive and former member of the Mississippi House of Representatives

- Ruben Alexander Sharp - former president of the United States, astronaut and current marine raider

In popular culture

editNon-fiction

editIn South and West: From a Notebook, Joan Didion recounts that she met a man while visiting Meridian in the 1970s who told her "The KKK which used to be a major factor in this community isn't a factor anymore, both the membership and the influence have diminished, and I cannot think of any place where the black is denied entrance, with the possible exception of private clubs."[202]

Fictional characters

editCullen Bohannon, the protagonist of the AMC series Hell on Wheels, hails from Meridian, Mississippi, where he is a tobacco farmer and later a Confederate soldier during the American Civil War.[203]

In the movie X-Men, the character Rogue hails from Meridian, Mississippi, and a small portion of the movie takes place there.

In the book To Kill a Mockingbird by Harper Lee, one of the characters, Dill Harris, is from Meridian.[204]

References

edit- ^ "2020 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved July 24, 2022.

- ^ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Archived from the original on May 31, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2011.

- ^ "Meridian city, Mississippi - Census Bureau Profile". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 1, 2023.

- ^ a b c d Campbell Robertson, "Last Chapter for a Courthouse Where Mississippi Faced Its Past", New York Times, September 18, 2012, p. 1, 16

- ^ a b c d e "History of Meridian, MS". Official website of Meridian, MeridianMS.org. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ Cook, Jody (December 4, 1979). "NRHP Nomination:McLemore Cemetery". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Meridian Multiple Resource Area Nomination" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. December 18, 1979. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "History of Meridian, MS". Don E. Wright. January 15, 2004. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "City of Meridian, MS – Attractions". Official Site of Meridian, MeridianMS.org. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ a b Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration (Miss.) (1938). Mississippi:A Guide to the Magnolia State. New York: Hastings House.

- ^ Nussbaum, Mick (August 5, 2007). "Meridian Railroad History". National Railway Historical Society, Queen & Crescent Chapter. Archived from the original on December 30, 2010. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ Sherman, William T. (January 21, 1875). "Memoirs of General W.T. Sherman – Meridian Campaign". St. Louis, Missouri. Archived from the original on January 12, 2013. Retrieved June 2, 2010.

- ^ a b Dougherty, Kevin (April 2007). "Sherman's Meridian Campaign: A Practice Run for the March to the Sea". Mississippi History Now. Mississippi Historical Society. Archived from the original on June 10, 2011. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ "Grand Opera House Project". Archived from the original on February 9, 2010. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ "The Wechsler Project". Archived from the original on July 13, 2009. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ McKee, Anne (January 10, 2008). "I could write a book..." The Meridian Star. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ "Intelligent Travel: The Tallest Threefoot Building in Town". Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g National Register of Historic Places nomination form for Meridian Downtown Historic District. January 16, 2007. National Park Service.

- ^ a b "Biography of Michael Schwerner". University of Missouri-Kansas City. Archived from the original on May 15, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ "Mississippi: Subversion of the Right to Vote" (PDF). Civil Rights Movement Archive. p. 5. Retrieved January 5, 2010.

- ^ Klopfer, Susan. "Civil Rights Murders". Archived from the original on May 1, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ Hart, Ariel (June 24, 2005). "41 Years Later, Ex-Klansman Gets 60 Years in Civil Rights Deaths". The New York Times. Retrieved August 22, 2009.

- ^ "43rd Annual Mississippi Civil Rights Martyrs Memorial Service and Conference and Caravan for Justice". Civil Rights Movement Archive. May 10, 2007. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010. Retrieved August 21, 2009.

- ^ a b "Union Station History". Official website of Meridian, MeridianMS.org. Archived from the original on May 9, 2008. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ a b Jeter, Lynne (July 19, 2004). "Strategic center of the South, Meridian poised for takeoff". The Mississippi Business Journal. Meridian, MS: BNET Business Network. Archived from the original on July 28, 2009. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ "MSU Riley Center – History and Renovation". Archived from the original on December 23, 2007. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ Jacob, Jennifer (December 19, 2007). "Meridian Star – Downtown Alliance Takes Over Main Street Organization". Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ a b c Brown, Jennifer Jacob (November 18, 2009). "Meridian Star – Working Together". The Meridian Star. Archived from the original on January 11, 2013. Retrieved May 25, 2010.

- ^ Jacob, Jennifer (January 2, 2010). "Barry, Smith make plans for 2010". The Meridian Star. Meridian, MS. Archived from the original on September 10, 2012. Retrieved January 26, 2010.

- ^ a b c Shank, Jack (1986). "Chapter 2: A City of Hotels". Meridian: The Queen with a Past. Vol. II. Meridian, Mississippi: Southeastern Printing Company. pp. 6–12. ISBN 0-9616123-2-0.

- ^ "Elmira Hotel". City of Meridian. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ^ "Terminal Hotel". City of Meridian. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ^ a b c d "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. January 23, 2007.

- ^ "Lamar Hotel". Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ "The Legacy". E.F. Young, Jr., Manufacturing Company. 1999. Archived from the original on July 4, 2008. Retrieved January 4, 2012.

- ^ Brown, Jennifer Jacob (June 27, 2010). "Threefoot Building: Part 1 'Looking at all our options': Development, demolition and stabilization". The Meridian Star. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ Frye, Georgia E. (August 20, 2006). "Riley Center officials get set to go". The Meridian Star. Archived from the original on July 12, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ Brown, Jennifer Jacob (June 12, 2011). "City working on downtown hotel". The Meridian Star. Archived from the original on July 10, 2012. Retrieved January 5, 2012.

- ^ "Historic Neighborhoods in Meridian". Official website of Meridian, MeridianMS.org. Archived from the original on July 6, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2006.

- ^ "U.S. Gazetteer Files: 2019: Places: Mississippi". U.S. Census Bureau Geography Division. Retrieved March 31, 2020.

- ^ "Meridian, MS". Netdoor.com. 2003. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ "Meridian, MS Weather". IDcide. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ Mean monthly maxima and minima (i.e. the expected highest and lowest temperature readings at any point during the year or given month) calculated based on data at said location from 1991 to 2020.

- ^ "NOWData – NOAA Online Weather Data". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ "Station: Meridian Key FLD, MS". U.S. Climate Normals 2020: U.S. Monthly Climate Normals (1991-2020). National Oceanic & Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved May 16, 2021.

- ^ "World Meteorological Organization Standard Normals 1961–1990". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved May 22, 2021.

- ^ "Explore Census Data". data.census.gov. Retrieved December 8, 2021.

- ^ a b "Meridian, MS, Comprehensive Revitalization Plan" (PDF). Official Website of Meridian, MS. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 11, 2008. Retrieved June 30, 2009.

- ^ a b c d "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ^ "Population Estimates for All Places: 2000–2008". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on July 4, 2009. Retrieved July 2, 2009.

- ^ "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Population of Metropolitan and Micropolitan Statistical Areas: April 1, 2000 to July 1, 2009 (CBSA-EST2009-01)". 2009 Population Estimates. United States Census Bureau, Population Division. March 23, 2010. Archived from the original (CSV) on June 15, 2010. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Meridian, Mississippi Workforce". East Mississippi Business Development Corporation. Archived from the original on July 4, 2020. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ a b "Meridian, Mississippi City Data". Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ "Association of Religion Data Archives – Lauderdale County, Mississippi". 2002. Retrieved June 17, 2010.

- ^ a b Brown, Jennifer Jacob (September 27, 2009). "Jewish Influence Shaped Meridian's History". The Meridian Star. Archived from the original on January 11, 2013. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "History of Congregations Beth Israel & Ohel Jacob, Meridian, Mississippi". Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities. Institute of Southern Jewish Life. Archived from the original on October 5, 2007. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Meridian, Mississippi". Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities. Institute of Southern Jewish Life. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ a b Jacob, Jennifer (December 25, 2007). "Queen Kelly Mitchell; a slice of Meridian's history". Meridian Star. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ Brown, Jennifer Jacob (February 13, 2011). "Fortune telling ordinance challenged". Meridian Star. Retrieved June 23, 2022.

- ^ "East Mississippi Business Development Corporation – About Us". East Mississippi Business Development Corporation. Archived from the original on August 4, 2020. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ a b c "MDES Annual Labor Force Report" (PDF). Mississippi Department of Employment Security. 2010. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 27, 2010. Retrieved June 9, 2010.

- ^ "East Mississippi Business Development Corporation". Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ "No. 3: Anderson RMC buys Riley Hospital". The Meridian Star. January 1, 2011. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ Morris, Joe. "Services, Location Top the List of Meridian's Health Care Strengths". Images East Mississippi. Archived from the original on March 25, 2011. Retrieved July 30, 2010.

- ^ a b "Trotman Company – Meridian Crossroads". The Trotman Company. Archived from the original on October 4, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ a b "Bonita Lakes Mall Fact Sheet". CBL & Associates Properties, Inc. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved June 9, 2008.

- ^ "City of Meridian, Mississippi: Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2007" (PDF). City of Meridian. March 18, 2008. Archived from the original (PDF) on August 8, 2008. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ a b "Business & Industry in Meridian, MS". Official website of Meridian, MeridianMS.org. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ a b c "City of Meridian, Mississippi: Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for the Fiscal Year Ended September 30, 2008" (PDF). City of Meridian. March 18, 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 4, 2011. Retrieved August 26, 2009.

- ^ "Key Field ANG Base Meridian RAP, Mississippi". GlobalSecurity.org. January 21, 2006. Retrieved June 7, 2008.

- ^ "General Information". Meridian Airport Authority. Archived from the original on January 6, 2010. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- ^ "Meridian, MS Annual Report 2007" (PDF). Official website of Meridian, MeridianMS.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 29, 2008. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ "Loeb's – Our Store". Loeb's Department Store. Archived from the original on August 3, 2020. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- ^ McKee, Anne (April 26, 2007). "The Little Museum that could, and did, thrives into the Twenty-First century". Meridian Star. Archived from the original on September 4, 2012. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Culture & Recreation". City of Meridian. July 12, 2008. Archived from the original on August 22, 2009. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Meridian Council for the Arts – Who We Are". Meridian Council for the Arts. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Meridian Council for the Arts – Our Partners". Meridian Council for the Arts. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved May 26, 2010.

- ^ "Meridian Little Theatre: History". Meridian Little Theatre. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Meridian Symphony Orchestry – About Us". Archived from the original on September 27, 2010. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ "Symphony's 50th Anniversary Celebration Feb. 26". WTOK-TV. January 27, 2011. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved January 27, 2011.

- ^ a b Mitchell, Dennis J. "Mississippi History Now – Grand Opera House of Mississippi". Mississippi Historical Society. Archived from the original on August 24, 2010. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- ^ "Grand Opera House Project". City of Meridian. July 12, 2008. Archived from the original on December 23, 2008. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "MSU Riley Center Overview". Mississippi State University Meridian Campus. July 8, 2008. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ^ "Mississippi Arts and Entertainment Center – About Us". Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved May 24, 2010.