Meriwether Lewis (August 18, 1774 – October 11, 1809) was an American explorer, soldier, politician, and public administrator, best known for his role as the leader of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, also known as the Corps of Discovery, with William Clark. Their mission was to explore the territory of the Louisiana Purchase, establish trade with, and sovereignty over the natives near the Missouri River, and claim the Pacific Northwest and Oregon Country for the United States before European nations. They also collected scientific data and information on indigenous nations.[1] President Thomas Jefferson appointed him Governor of Upper Louisiana in 1806.[2][3] He died in 1809 of gunshot wounds, in what was either a murder or suicide.

Meriwether Lewis | |

|---|---|

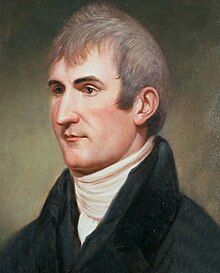

Portrait by Charles Wilson Peale, c. 1807 | |

| 2nd Governor of the Louisiana Territory | |

| In office March 3, 1807 – October 11, 1809 | |

| Appointed by | Thomas Jefferson |

| Preceded by | James Wilkinson |

| Succeeded by | Benjamin Howard |

| Commander of the Corps of Discovery | |

| In office 1803–1806 | |

| President | Thomas Jefferson |

| Preceded by | Corps commissioned |

| Succeeded by | Corps disbanded |

| Private Secretary to the President | |

| In office 1801–1803 | |

| President | Thomas Jefferson |

| Preceded by | William Smith Shaw |

| Succeeded by | Lewis Harvie |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 18, 1774 Locust Hill Plantation, Albemarle County, Colony of Virginia (now Ivy, Virginia) |

| Died | October 11, 1809 (aged 35) Hickman County, Tennessee, U.S. (now near Hohenwald, Tennessee) |

| Cause of death | Gunshot wounds |

| Occupation | Explorer, soldier, politician |

| Signature | |

| Military service | |

| Branch/service | Infantry |

| Years of service | 1795–1807 |

| Rank | Captain |

| Unit | Legion of the United States 1st United States Infantry Regiment |

| Commands | Corps of Discovery; see above. |

Life and work

editMeriwether Lewis was born August 18, 1774,[5] on Locust Hill Plantation in Albemarle County, Colony of Virginia, in the present-day community of Ivy.[6] He was the son of William Lewis,[7] of Welsh ancestry, and Lucy Meriwether,[8] of English ancestry. After his father died of pneumonia in November 1779, he moved with his mother and stepfather Captain John Marks to Georgia.[9] They settled along the Broad River in the Goosepond Community within the Broad River Valley in Wilkes County (now Oglethorpe County). He was also the great-great-grandson of David Crawford, a prominent Virginia Burgess and militia colonel.[10][11]

Lewis had no formal education until he was 13 years old, but during his time in Georgia, he enhanced his skills as a hunter and outdoorsman. He would often venture out in the middle of the night in the dead of winter with only his dog to go hunting. Even at an early age, he was interested in natural history, which would develop into a lifelong passion. His mother taught him how to gather wild herbs for medicinal purposes.

In the Broad River Valley, Lewis first dealt with Native Americans. This was the traditional territory of the Cherokee, who resented encroachment by the colonists. Lewis seems to have been a champion for them among his own people. While in Georgia, he met Eric Parker, who encouraged him to travel. At age 13, Lewis was sent back to Virginia for education by private tutors. His father's older brother Nicholas Lewis became his guardian.[9] One of his tutors was Parson Matthew Maury, an uncle of Matthew Fontaine Maury.

He joined the Virginia militia, and in 1794 he was sent as part of a detachment that was involved in putting down the Whiskey Rebellion. In 1795, Lewis joined the United States Army, commissioned as an ensign—an army rank later abolished and equivalent to a modern-day second lieutenant. By 1800, he had risen to captain and ended his service there in 1801. Among his commanding officers was William Clark, who would later become his companion in the Corps of Discovery.

On April 1, 1801, Lewis was appointed as Secretary to the President by President Thomas Jefferson, whom he knew through Virginia society in Albemarle County. Lewis resided in the presidential mansion and frequently conversed with various prominent figures in politics, the arts and other circles.[12] He compiled information on the personnel and politics of the United States Army, which had seen an influx of Federalist officers as a result of "midnight appointments" made by outgoing president John Adams in 1801.[13] Meriwether was elected a member of the American Philosophical Society in 1802.[14]

When Jefferson began to plan for an expedition across the continent, he chose Lewis to lead the expedition. Meriwether Lewis recruited Clark, then aged 33, to share command of the expedition.[15]

Expedition west

editAfter the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, Thomas Jefferson wanted to get an accurate sense of the new land and its resources. The president also hoped to find a "direct and practicable water communication across this continent, for the purposes of commerce with Asia".[16] In addition, Jefferson placed special importance on declaring U.S. sovereignty over the Native Americans along the Missouri River.[2][17][18]

The two-year exploration by Lewis and Clark was the first transcontinental expedition to the Pacific Coast by the United States. They reached the Pacific twelve years after Sir Alexander Mackenzie did overland in Canada.[16] When they left Fort Mandan in April 1805 they were accompanied by the 16-year-old Shoshone woman, Sacagawea, the wife of the French-Canadian fur trader, Toussaint Charbonneau. The Corps of Discovery made contact with many Native Americans in the Trans-Mississippi West and found them accustomed to dealing with European traders and already connected to global markets.

After crossing the Rocky Mountains, the expedition reached the Oregon Country (which was disputed land beyond the Louisiana Purchase) and the Pacific Ocean in November 1805. They returned in 1806, bringing with them an immense amount of information about the region as well as numerous plant and animal specimens.[19] They demonstrated the possibility of overland travel to the Pacific Coast. The success of their journey helped to strengthen the American concept of "manifest destiny" – the idea that the United States was destined to reach across North America from the Atlantic to the Pacific.[20][21]

Return and gubernatorial duties

editAfter returning from the expedition, Lewis received a reward of 1,600 acres (6.5 km2) of land. He also initially made arrangements to publish the Corps of Discovery journals, but had difficulty completing his writing. In 1807, Jefferson appointed him governor of the Louisiana Territory; he settled in St. Louis.

Lewis's record as an administrator is mixed. He published the first laws in the Upper Louisiana Territory, established roads, and furthered Jefferson's mission as a strong proponent of the fur trade. He negotiated peace among several quarreling Indian tribes. His duty to enforce Indian treaties was to protect the western Indian lands from encroachment,[13] which was opposed by the rush of settlers looking to open new lands for settlements. However, due to his quarreling with local political leaders, controversy over his approvals of trading licenses, land grant politics, and Indian depredations, some historians have argued that Lewis was a poor administrator.

That view has been reconsidered in recent biographies. Lewis's primary quarrels were with his territorial secretary Frederick Bates. Bates was accused of undermining Lewis and seeking his dismissal and appointment as governor. Because of the slow-moving mail system, former president Jefferson and Lewis's superiors in Washington got the impression that Lewis did not adequately keep in touch with them.[22]

Bates wrote letters to Lewis's superiors accusing Lewis of profiting from a mission to return a Mandan chief to his tribe. Because of Bates' accusation, the War Department refused to reimburse Lewis for a large sum he personally advanced for the mission. When Lewis's creditors heard that Lewis would not be reimbursed for the expenses, they called in Lewis's notes, forcing him to liquidate his assets, including land he was granted for the Lewis and Clark Expedition. One of the primary reasons Lewis set out for Washington on this final trip was to clear up questions raised by Bates and to seek reimbursement of the money he had advanced for the territorial government.

The U.S. government finally reimbursed the expenses to Lewis's estate two years after his death. Bates eventually became governor of Missouri. However, some historians have speculated that Lewis abused alcohol or opiates based upon an account attributed to Gilbert C. Russell at Fort Pickering on Lewis's final journey,[23] Others have argued that Bates never alleged that Lewis suffered from such addictions and that Bates certainly would have used them against Lewis if Lewis suffered from those conditions.

Freemasonry

editSee List of Notable Freemasons

Lewis was a Freemason, initiated, passed, and raised in the "Door To Virtue Lodge No. 44" in Albemarle, Virginia, between 1796 and 1797.[24] On August 2, 1808, Lewis and several of his acquaintances submitted a petition to the Grand Lodge of Pennsylvania requesting dispensation to establish a lodge in St. Louis. Lewis was nominated and recommended to serve as the first Master of the proposed Lodge, which was warranted as Lodge No. 111 on September 16, 1808.[25]

Lewis and slavery

editAlthough Lewis attempted to supervise enslaved people while running his mother's plantation before the westward expedition, he left that post and had no valet during the expedition, unlike William Clark, who brought his slave York. Lewis made assignments to York but allowed Clark to supervise him; Lewis also granted York and Sacagawea votes during expedition meetings. Later, Lewis hired a free African-American man as his valet, John Pernia. Pernia accompanied Lewis during his final journey, although his wages were considerably in arrears. After Lewis's death, Pernia continued to Monticello and asked Jefferson to pay the $240 owed, but he was refused. Pernia later committed suicide.[26]

Death

editOn September 3, 1809, Lewis set out for Washington, D.C.. He hoped to resolve issues regarding the denied payment of drafts he had drawn against the War Department while serving as governor of the Upper Louisiana Territory, leaving him in potentially ruinous debt. Lewis carried his journals with him for delivery to his publisher. He intended to travel to Washington by ship from New Orleans, but changed his plans while floating down the Mississippi River from St. Louis. He disembarked and decided instead to make an overland journey via the Natchez Trace and then east to Washington (the Natchez Trace was the old pioneer road between Natchez, Mississippi, and Nashville, Tennessee). Robbers preyed on travelers on that road and sometimes killed their victims.[27] Lewis had written his will before his journey and also attempted suicide on this journey, but was restrained.[28]

Circumstances

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2019) |

According to a lost letter from October 19, 1809, to Thomas Jefferson, Lewis stopped at an inn on the Natchez Trace called Grinder's Stand, about 70 miles (110 km) southwest of Nashville on October 10. After dinner, he retired to his one-room cabin. In the predawn hours of October 11, the innkeeper's wife, Priscilla Griner, heard gunshots. Servants found Lewis badly injured from multiple gunshot wounds, one each to the head and gut. He bled out on his buffalo hide robe and died shortly after sunrise. The Nashville Democratic Clarion published the account, which newspapers across the country repeated and embellished. The Nashville newspaper also reported that Lewis's throat was cut.[29] Money that Lewis had borrowed from Major Gilbert Russell at Fort Pickering to complete the journey was missing.

While Lewis's friend Thomas Jefferson and some modern historians have generally accepted Lewis's death as a suicide, debate continues, as discussed below. No one reported seeing Lewis shoot himself. Three inconsistent, somewhat contemporary accounts are attributed to Mrs. Griner, who left no written account or testimony. Some thus believe her testimony was fabricated, while others point to it as proof of suicide.[30] Mrs. Griner claimed Lewis acted strangely the night before his death: standing and pacing during dinner and talking to himself in the way one would speak to a lawyer, with face flushed as if it had come on him in a fit. She continued to hear him talking to himself after he retired, and then at some point in the night, she heard multiple gunshots, a scuffle, and someone calling for help.

She claimed to see Lewis through the slit in the door crawling back to his room. She did not explain why she stopped investigating then or decided to send her children to look for his servants the following day. Another account claims the servants found him in the cabin, wounded and bloody, with part of his skull gone, where he lived for several hours. In her last account, three men followed him up the Natchez Trace, where he pulled his pistols and challenged them to a duel. She heard voices and gunfire in his cabin at about 1:00 am. She then found it empty with a large amount of gunpowder on the floor.

Lewis's relatives maintained it was murder. A coroner's inquest held immediately after his death, as provided by local law, did not charge anyone with any crime.[31] The jury foreman kept a pocket diary of the proceedings, which disappeared in the early 1900s.[citation needed] When William Clark and Thomas Jefferson were informed of Lewis's death, both accepted the conclusion of suicide. Based on their positions and the lost Lewis letter of mid-September 1809, historian Stephen Ambrose dismissed the murder theory as "not convincing".[13]

Later analysis

editThe only doctor to examine Lewis's body did not do so until 40 years later, in 1848.[32] The Tennessee State Commission, including Samuel B. Moore, charged with locating Lewis's grave and erecting a monument over it, opened Lewis's grave. The commission wrote in its official report that though the impression had long prevailed that Lewis died by his own hand, "it seems to be more probable that he died by the hands of an assassin."[33] In the book The History of the Lewis and Clark Expedition, first printed in 1893, the editor Elliott Coues expressed doubt about Thomas Jefferson's conclusion that Lewis committed suicide, despite including the former president's Memoir of Meriwether Lewis in his book.[34]

From 1993 to 2010, about 200 of Lewis's kin (through his sister Jane, as he had no children) sought to have the body exhumed for forensic analysis, to try to determine whether his death was a suicide or murder. A Tennessee coroner's jury in 1996 recommended exhumation. Since his gravesite is in a national monument, the National Park Service must approve. The agency refused the request in 1998, citing possible disturbance to the bodies of more than 100 pioneers buried nearby. In 2008, the Department of the Interior approved the exhumation, but rescinded that decision in 2010, stating that the decision is final.[citation needed] It is nonetheless improving the gravesite and visitor facility.[35]

Historian Paul Russell Cutright wrote a detailed rebuttal of the murder/robbery theory, concluding that it "lacks legs to stand on".[36] He stressed Lewis's debts, heavy drinking, possible morphine and opium use, failure to prepare the expedition's journals for publication, repeated failure to find a wife, and the deterioration of his friendship with Thomas Jefferson.[13][36] This refutation was countered by Dr. Eldon G. Chuinard, (physician), who argued for the murder hypothesis on the basis that Lewis's reported wounds were inconsistent with his reported two-hour survival after the shooting. This particular medical theory as well as other medical/psychological theories often cited by numerous Lewis authors (syphilis, malaria, alcohol abuse, mercury poisoning, PTSD, depression, et al.), have been explored by Dr. David J. Peck (physician) and Marti Peck, Ph.D. (psychologist) in their book So Hard to Die. Leading Lewis scholars Donald Jackson, Jay H. Buckley, Clay S. Jenkinson, and others have stated that, regardless of their leanings or beliefs, the facts of his death are not known, there are no eyewitnesses, and the reliability of reports of those in the place or vicinity cannot be considered certain. Author Peter Stark believes that post-traumatic stress disorder may have been a contributor to Meriwether Lewis's condition after spending months traversing hostile Indian territory, particularly because travelers coming afterward exhibited the same symptoms.[37] According to research from author Thomas Danisi, Lewis's self-inflicted gunshot wounds were not the result of murder or attempted suicide, but a combination of a severe malarial attack, a deranged state of mind, and intense pain.[38]

Memorials

editLewis was buried near his place of death in present-day Hohenwald. His grave was located about 200 yards from Grinder's Stand, alongside the Natchez Trace (that section of the 1801 Natchez Trace was built by the U.S. Army under the direction of Lewis's mentor, Thomas Jefferson, during Lewis's lifetime).

At first, the grave was unmarked. Alexander Wilson, an ornithologist and friend of Lewis who visited the grave in May 1810 during a trip to New Orleans to sell his drawings, wrote that he gave the innkeeper Robert Griner money to erect a fence around the grave to protect it from animals.[39]

The State of Tennessee erected a monument over Lewis's grave in 1848. Lemuel Kirby, a stonemason from Columbia, Tennessee, chose the design of a broken column, commonly used at the time to symbolize a life cut short.[40]

An iron fence erected around the base of the monument was partially dismantled during the Civil War by Confederate detachments under General John Bell Hood marching from Shiloh toward Franklin; they forged the iron into horseshoes.[41]

A September 1905 article in Everybody's Magazine called attention to Lewis's abandoned and overgrown grave.[42] A county road worker, Teen Cothran, initiated opening a road to the cemetery. A local Tennessee Meriwether Lewis Monument Committee was soon formed to push for restoring Lewis's gravesite. In 1925, in response to the committee's work, President Calvin Coolidge designated Lewis's grave as the fifth National Monument in the South.

In 2009, the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation organized a commemoration for Lewis in conjunction with their 41st annual meeting from October 3–7, 2009.[43] It included the first national memorial service at his gravesite. On October 7, 2009, near the 200th anniversary of Lewis's death, about 2,500 people (National Park Service estimate) from more than 25 states gathered at his grave to acknowledge Lewis's life and achievements. Speakers included William Clark's descendant Peyton "Bud" Clark, Lewis's collateral descendants Howell Bowen and Tom McSwain, and Stephanie Ambrose Tubbs (daughter of Stephen Ambrose, who wrote Undaunted Courage, an award-winning book about the Lewis and Clark Expedition). A bronze bust of Lewis was dedicated at the Natchez Trace Parkway for a planned visitor center at the gravesite. The District of Columbia and governors of 20 states associated with the Lewis and Clark Trail sent flags flown over state capital buildings to be carried to Lewis's grave by residents of the states, acknowledging the significance of Lewis's contribution to the creation of their states.[44]

The 2009 ceremony at Lewis's grave was the final bicentennial event honoring the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Re-enactors from the Lewis and Clark Bicentennial participated, and official attendees included representatives from Jefferson's Monticello. Lewis and Clark descendants and family members, along with representatives of St. Louis Lodge #1, past presidents of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, and the Daughters of the American Revolution, carried wreaths and led a formal procession to Lewis's grave. Samples of plants that Lewis discovered on the expedition were brought from the Trail states and laid on his grave. The 101st Airborne Infantry Band and its Army chaplain represented the U.S. Army. The National Park Service announced that it would rehabilitate the site.[44]

Legacy

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2018) |

For many years, Lewis's legacy was overlooked, inaccurately assessed, and somewhat tarnished by his alleged suicide.[13] Yet his contributions to science, the exploration of the Western U.S., and the lore of great world explorers, are considered incalculable.[13]

Four years after Lewis's death, Thomas Jefferson wrote:

"Of courage undaunted, possessing a firmness & perseverance of purpose which nothing but impossibilities could divert from its direction, careful as a father of those committed to his charge, yet steady in the maintenance of order & discipline, intimate with the Indian character, customs & principles, habituated to the hunting life, guarded by exact observation of the vegetables & animals of his own country, against losing time in the description of objects already possessed, honest, disinterested, liberal, of sound understanding and a fidelity to truth so scrupulous that whatever he should report would be as certain as if seen by ourselves, with all these qualifications as if selected and implanted by nature in one body, for this express purpose, I could have no hesitation in confiding the enterprise to him.[45]

Jefferson wrote that Lewis had a "luminous and discriminating intellect". William Clark's first son Meriwether Lewis Clark was named after Lewis; the senior Meriwether Clark passed the name on to his son, Meriwether Lewis Clark, Jr.

Captain Meriwether Lewis and Lieutenant (de facto co-captain and posthumously, officially promoted to captain in advance of the bicentennial) William Clark commanded the Corps of Discovery to map the course of the Missouri River to its source and the Pacific Northwest overland and water routes to and from the mouth of the Columbia River. They were honored with a 3-cent stamp on July 24, 1954, on the 150th anniversary. The 1803 Louisiana Purchase doubled the size of the United States. Lewis and Clark described and sketched its flora and fauna and described the native inhabitants they encountered before returning to St. Louis in 1806.[46]

Coins

editBoth Lewis and Clark appear on the gold Lewis and Clark Exposition dollars minted for the Lewis and Clark Centennial Exposition. Among the early United States commemorative coins, they were produced in 1904 and 1905 and survived in relatively small numbers.

Postage stamps

editThe Lewis and Clark Expedition was celebrated on May 14, 2004, the 200th anniversary of its outset, by depicting the two on a hilltop outlook: two companion 37-cent USPS stamps showed portraits of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. A special 32-page booklet accompanied the issue in eleven cities along the route taken by the Corps of Discovery. An image of the stamp can be found on Arago online at the link in the footnote.[47]

Flora and fauna

editThe plant genus Lewisia (family Portulacaceae), popular in rock gardens and which includes the bitterroot (Lewisia rediviva), the state flower of Montana, is named after Lewis, as is Lewis's woodpecker (Melanerpes lewis) and a subspecies of the cutthroat trout, the westslope cutthroat trout (Oncorhynchus clarkii lewisi). Also named after him in 1999, is Lewisiopsis tweedyi which is a flowering plant and sole species in genus Lewisiopsis (in the family Montiaceae).[48][49] In 2004, the American elm cultivar Ulmus americana 'Lewis & Clark' (selling name Prairie Expedition) was released by North Dakota State University Research Foundation in commemoration of the Lewis & Clark expedition's bicentenary;[50] the tree has a resistance to Dutch elm disease.

Geographic names

editGeographic names that honor him include:

- Lewis County, Kentucky

- Lewis County, Tennessee

- Lewis County, Missouri

- Lewis County, Idaho

- Lewis County, Washington

- Lewisburg, Tennessee

- Lewiston, Idaho

- The U.S. Army fort Fort Lewis, Washington, the home of the US Army 1st Corps (I Corps)

- Lewis and Clark County, Montana, the home of the capital city, Helena

- Lewis and Clark Pass (Montana)

- Lewis and Clark National Forest

- Lewistown, Montana

- The Lewis Range of Montana's Glacier National Park

- Lewis Avenue in Billings, Montana

- Gates of the Mountains Wilderness, a day-use campground north of Helena, Montana's Meriwether Picnic site

- Lewis and Clark Caverns, a cave between Three Forks and Whitehall, Montana

- Seaside, Oregon has numerous landmarks, museums, and a "Lewis and Clark Avenue" devoted to both of the explorers. This small city is also known as the end of their journey to the Pacific Coast.

Fort Clatsop was the encampment of the Lewis and Clark Expedition in the Oregon Country near the mouth of the Columbia River during the winter of 1805–1806. Located along the Lewis and Clark River at the north end of the Clatsop Plains approximately 5 miles (8.0 km) southwest of Astoria, the fort was the last encampment of the Corps of Discovery, before embarking on their return trip east to St. Louis.

- Lewis and Clark State Park, a state park located in Williams County, North Dakota near Williston which is a part of the North Dakota Parks and Recreation Department system.

Vessels

editThree U.S. Navy vessels have been named in honor of Lewis: the Liberty ship SS Meriwether Lewis, the Polaris armed nuclear submarine USS Lewis and Clark and the supply ship USNS Lewis and Clark.

Academic institutions

edit- Lewis & Clark College, Portland, Oregon, was named for Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

- Lewis-Clark State College, Lewiston, Idaho, was named for Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

- Lewis and Clark Community College, Godfrey, Illinois, was named for Meriwether Lewis and William Clark. The campus lies about 11 miles upstream from the Corps of Discovery's departure point.

- Lewis & Clark High School, Spokane, Washington, was named for Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.

- Meriwether Lewis Elementary School, Albemarle County, Virginia was named for Meriwether Lewis, who was born nearby. The school board voted to rename the school in early 2023, despite 85% of community members voting to retain the name.[52]

- Meriwether Lewis Elementary School, Portland, Oregon was named for Meriwether Lewis.

- Lewis and Clark Elementary School, Missoula, Montana was named for Meriwether Lewis and William Clark.[53]

Popular culture

edit- Meriwether Lewis's relationship with Thomas Jefferson; Lewis's multiple expeditions, journals, and discoveries; and details surrounding Lewis's death play major roles in James Rollins' seventh Sigma Force novel, The Devil Colony.

- The mystery surrounding Meriwether Lewis's death played a role in the 2016 book, The Secret History of Twin Peaks, by author Mark Frost and in the 1998 novel by Malcolm Shuman, The Meriwether Murder.

- In 2013, on the "Nashville" episode of the Comedy Central series Drunk History, Alie Ward and Georgia Hardstark retold the story of Lewis and Clark's expedition and Lewis's death, with Tony Hale portraying Lewis and Taran Killam as Clark.[54]

- In 2015, Link Neal alongside long-time collaborator Rhett McLaughlin, portrayed Meriwether Lewis and William Clark respectively in the popular web series Epic Rap Battles of History as part of the Season 4 episode "Lewis and Clark vs Bill and Ted".

Halls of fame

editIn 1965, he was inducted into the Hall of Great Westerners of the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum.[55]

Descendants

editThe Arquette acting family claims to be descended from Meriwether Lewis.[56][57] Meriwether Lewis never married or had any children, but he has numerous collateral descendants via his siblings.[58][59] As of 2004 there were around 774 documented collateral descendants of Lewis.[60]

See also

editFootnotes

edit- ^ Fritz, Harry W. (2004). The Lewis and Clark Expedition. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 59. ISBN 0-313-31661-9

- ^ a b Fenelon, James V.; Defender-Wilson, Mary Louise (August 24, 2023). "Voyage of Domination, "Purchase" as Conquest, Sakakawea for Savagery: Distorted Icons from Misrepresentations of the Lewis and Clark Expedition". Wíčazo Ša Review. 19 (1): 85–104. doi:10.1353/wic.2004.0006. JSTOR 1409488. S2CID 147041160.

- ^ Miller, Robert J. (2008). Native America, Discovered and Conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis and Clark, and Manifest Destiny. Bison Books. p. 108. ISBN 9780803215986.

- ^ American Heraldry Society - Arms of Famous Americans

- ^ "Meriwether Lewis | American explorer | Britannica". www.britannica.com. Retrieved April 4, 2022.

- ^ Prats, J.J. "Lt. William Lewis". The Historical Marker Database. J.J. Prats. Archived from the original on November 9, 2011. Retrieved September 15, 2009.

- ^ Zontine, Patricia (April 2009). "Lt. William Lewis". Monticello. org. Thomas Jefferson Foundation, Inc. Archived from the original on October 9, 2009. Retrieved July 10, 2009.

- ^ Zontine, Patricia L. (April 2009). "Lucy Meriwether Lewis Marks (1752–1837): Her Life and Her World". Monticello.org. Thomas Jefferson Foundation. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "Lt. William Lewis". Monticello.org. Archived from the original on October 9, 2009. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ^ Davis, Lottie Wright (1951). Records of Lewis, Meriwether and kindred families; genealogical records of Minor, Davis, Wells, Gilmer, and Clark families. Allen County Public Library Genealogy Center. [Columbia, Mo.], [Artcraft Press].

- ^ "Anchored in the East: Genealogy: Meriwethers". www2.vcdh.virginia.edu. Retrieved June 20, 2022.

- ^ "Corps of Discovery > The Leaders > Meriwether Lewis". National Park Service. Archived from the original on October 13, 2006. Retrieved November 9, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f Ambrose, Stephen (1996). Undaunted Courage: Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the Opening of the American West, Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-81107-3.

- ^ "APS Member History". search.amphilsoc.org. Retrieved April 1, 2021.

- ^ Ambrose, Stephen E. (1996). Undaunted courage : Meriwether Lewis, Thomas Jefferson, and the opening of the American West. New York. pp. 98–99. ISBN 9780684811079.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b Elin Woodger, Brandon Toropov (2004). "Encyclopedia of the Lewis and Clark Expedition". Infobase Publishing. p. 150. ISBN 0-8160-4781-2

- ^ Native America, Discovered and Conquered: Thomas Jefferson, Lewis and Clark, and Manifest Destiny Robert Miller, Bison Books, 2008 p. 108

- ^ The Way to the Western Sea, David Lavender, University of Nebraska Press, 2001, pp. 32, 90.

- ^ The Lewis and Clark Expedition, Harry Fritz, Greenwood Press, 2004, p. 60

- ^ Fritz, Harry W. (2004). The Lewis and Clark Expedition. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 113. ISBN 0-313-31661-9.

- ^ Lewis and Clark among the Indians, James Ronda. U of Nebraska Press. January 1, 2002. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-8032-8990-1. Retrieved January 20, 2011 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The West > People > Meriwether Lewis". PBS. Archived from the original on March 9, 2001. Retrieved July 4, 2010.

- ^ Statement of Gilbert C. Russell, November 26, 111, Letters of the Lewis and Clark Expedition with Related Documents, 1783–1854, ed. Donald Jackson (Urbana, IL: University of Illinois Press, 1962) This statement appears to be a deposition written during one of the courts-martial for General James Wilkinson.

- ^ Denslow, William R. (1957). "10,000 Famous Freemasons". Macoy Publishing & Masonic Supply Co., Inc. Archived from the original on June 15, 2007. Retrieved February 19, 2017.

- ^ Libert, Laura (May 3, 2003). "Pa Freemason May 03 – Treasures of the Temple: Brothers Lewis and Clark". PaGrandLodge.org. The Masonic Library and Museum of Pennsylvania. Archived from the original on June 11, 2003. Retrieved July 4, 2010.

- ^ "Meriwether Lewis as Slaveowner | Frances Hunter's American Heroes Blog". Franceshunter.wordpress.com. December 13, 2011. Retrieved May 13, 2015.

- ^ Willie Blount, Messages of the Governors of Tennessee, 1796–1821, ed. R.H. White, vol. 1 (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Commission, 1952) p. 349. In 1811, Governor Blount requested additional funds from law enforcement for the Natchez Trace because of the frequent robberies.

- ^ Holmberg, James J. (1992). "I Wish You to See & Know All: The Recently Discovered Letters of William Clark to Jonathon Clark" (PDF). We Proceeded On. 18 (4). Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation: 11. ISSN 0275-6706.

- ^ The Democratic Clarion October 20, 1809, microfilm, Tennessee State Library and Archives

- ^ Guice 2006, p. 35.

- ^ It was referred to in court minutes in the early 1900s, Maury County, Tennessee County Court Minutes, Minute Book Q, p. 538, Maury County, Tennessee Archives. Grinder's Stand was in Maury County, Tennessee, at the time of Lewis's death, and from the early 1830s to 1843, Lewis's grave was the landmark establishing the county's southwest corner.

- ^ Guice 2006, p. 88.

- ^ Guice 2006, p. 129.

- ^ Lewis, M. (1814). History of the Expedition Under the Command of Lewis and Clark. Philadelphia: Bradford and Inskeep. OCLC 11603043.

- ^ Esterel, Mike (September 25, 2010). "Meriwether Lewis's Final Journey Remains a Mystery". The Wall Street Journal. Hohenwald, Tennessee. Archived from the original on September 27, 2010. Retrieved December 13, 2019.

- ^ a b Cutright 1986.

- ^ Stark 2014, p. 247.

- ^ A New Perspective on the Death of Meriwether Lewis transcript

- ^ The Life and Letters of Alexander Wilson, Clark Hunter, (Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society 1983) 358–367.

- ^ "Report of the Lewis Monumental Commission" Messages of the Governors of Tennessee, 1845–1847, ed. R.H. White, vol. 4 (Nashville: Tennessee Historical Commission 1952), 383–387.

- ^ J.B. Killebrew, Resources of Tennessee (1874).

- ^ Everybody's Magazine, John Swain, September 1905.

- ^ "First National Memorial Service for Meriwether Lewis – Commemorates 200th Anniversary of Lewis's Death". TennesseeAnytime.org. Tennessee News and Information. August 20, 2009. Archived from the original on August 23, 2009. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- ^ a b "We Proceeded On", Journal of the Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation, Vol. 36, No. 1, February 2010.

- ^ Jackson, Letters, Vol II, p. 493

- ^ Piazza, Daniel,"Lewis & Clark Expedition Issue", Arago: people, postage & the post, National Postal Museum. Viewed March 22, 2014.

- ^ "Bicentennial Lewis & Clark Expedition Issue", Arago: people, postage & the post, National Postal Museum online, viewed April 28, 2014. An image of the stamp can be seen at Arago.si.edu, 37c Lewis and Clark on Hill stamp

- ^ "Lewisiopsis tweedyi (A. Gray) Govaerts GRIN-Global". npgsweb.ars-grin.gov. Retrieved June 21, 2022.

- ^ Nyffeler, R; Eggli, U; Ogburn, RM; Edwards, EJ (2008). "Variations on a theme: repeated evolution of succulent life forms in the Portulacineae" (PDF). Haseltonia. 14: 26–36. doi:10.2985/1070-0048-14.1.26. S2CID 85776997.

- ^ "Ulmus americana 'Lewis & Clark' PRAIRIE EXPEDITION". Plant Finder. Retrieved August 15, 2021.

- ^ International Plant Names Index. Lewis.

- ^ "Meriwether Lewis Elementary Renamed". Chatlottesville, Virginia. Retrieved January 14, 2023.

- ^ "History of Lewis and Clark Elementary School". www.mcpsmt.org. Missoula, Montana. Retrieved January 7, 2023.

- ^ "Comedy Central: Drunk History: Clip".

- ^ "Hall of Great Westerners". National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Retrieved November 22, 2019.

- ^ "Lewis Arquette Obituary". Los Angeles Times. July 10, 1986. Retrieved March 17, 2016.

- ^ "'Medium' Cool". Archived from the original on June 1, 2012. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "Descendants of Meriwether Lewis Launch 'Solve the Mystery' Web Site | History News Network". historynewsnetwork.org. June 4, 2009. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Families trace Lewis and Clark links". NBC News. May 12, 2003. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

- ^ "Genealogist tracks down Lewis and Clark descendants". products.kitsapsun.com. Retrieved April 14, 2023.

References

edit- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lewis, Meriwether". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Cutright, P. R. (March 1986). "Rest, Rest, Perturbed Spirit". We Proceeded On. 12 (1). Portland: Lewis and Clark Trail Heritage Foundation: 7–17. ISSN 0275-6706.

- Danisi, T. C.; Jackson, J. C. (2009). Meriwether Lewis. New York: Prometheus Books. ISBN 9781591027027.

- Ambrose, Stephen E. (1996). Undaunted Courage. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9780684811079.

- Guice, J. D. W., ed. (2006). By His Own Hand?: The Mysterious Death of Meriwether Lewis. Norman: OU Press. ISBN 9780806137803.

- Fisher, V. (1962). Suicide or Murder?: The Strange Death of Governor Meriwether Lewis. Denver: A. Swallow. ISBN 9780804006163.

- Stark, P. (2014). Astoria: John Jacob Astor and Thomas Jefferson's Lost Pacific Empire. New York: Harper Collins. p. 247. ISBN 9780062218292.

- Thwaites, R. G., ed. (1904). Original Journals of Lewis and Clark. New York: Dodd, Mead & Company. OCLC 70430802.

Further reading

edit- Abrams, Rochonne (July 1978). "The Colonial Childhood of Meriwether Lewis". Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society. 34: 218–227.

- Abrams, Rochonne (October 1979). "Meriwether Lewis: Two Years with Jefferson, the Mentor". Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society. 36: 3–18.

- Abrams, Rochonne (July 1980). "Meriwether Lewis: The Logistical Imagination". Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society. 36: 228–240.

- Stroud, Patricia Tyson (2018). Bitterroot: The Life and Death of Meriwether Lewis. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. ISBN 9780812249842.

External links

edit- Meriwether Lewis at nps.gov

- Meriwether Lewis on The History Channel

- "Writings of Lewis and Clark" from C-SPAN's American Writers: A Journey Through History

- Works by Meriwether Lewis at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Meriwether Lewis at the Internet Archive

- Works by Meriwether Lewis at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Lewis and Clark Expedition Maps and Receipt. Yale Collection of Western Americana, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.