This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

Mihail Fărcășanu (November 10, 1907 – July 14, 1987) was a Romanian journalist, diplomat and writer. He was president of the National Liberal Youth from 1937 to 1946.[1] Pursued by the authorities due to his anti-communist actions, he managed to flee the country in 1946, and was later sentenced to death.

He was member of the Romanian National Committee (Romanian: Comitetul Național Român) and the League of Free Romanians (Liga Românilor Liberi) where he was elected as president in 1953.[1] He was the first manager of the Romanian-language section of Radio Free Europe.[citation needed] His most important work is Frunzele nu mai sunt aceleași ("The Leaves Are No Longer the Same"), published in 1946 under the pen name Mihail Villara.[1] The work was given the Editura Cultura Națională Grand Prize.[citation needed]

Ancestry

editFărcășanu was a direct descendant of Popa Stoica from Fărcaș, Dolj County. Popa Stoica was a priest who abandoned the church and fought against the Ottoman Empire in the army of Michael the Brave, who later named him ağa, or supreme commander of the army.[citation needed] In 1595, Ağa Fărcaș led an army across the Danube, conquering the Bulgarian citadel Nikopol and marching to Vidin, where he was defeated by the Ottomans, and where he eventually died.[citation needed]

After Ağa Fărcaș, the family had a succession of such dignitaries as Radu Fărcășanu (captain in 1639, treasurer in 1654, stolnic in 1657 and mare vornic), Barbu Fărcășanu (logothete and treasurer in 1674), Matei Fărcășanu (great stolnic in 1731), Constantin Fărcășanu (serdar) and Enache Fărcășanu (Grand Panetier named ispravnic of Romanați).[2]

Youth and studies

editMihail Fărcășanu was born on November 10, 1907, in Bucharest, as the son of Gheorghe Fărcășanu and Mariei Fărcășanu (née Vasilescu).[1] His father had a bachelor's degree in law but he never practiced. Besides Mihail, the parents had three other boys, Gheorghe, Paul (adopted by an uncle, Paul Zotta), and Nicu, and two girls, Margareta (married Bottea) and Mia (married Lahovari). His parents lived in Râmnicu Vâlcea, where Fărcășanu attended primary school and then high school at Alexandru Lahovari High School (now Alexandru Lahovari National College),[3] graduating in 1927 magna cum laude. In 1935 he attended the London School of Economics, where he studied under Harold Laski; Laski would go on to become president in 1945–1946 of the Labour Party in the United Kingdom.[1]

He completed his legal studies in Germany at the Friedrich Wilhelm University (since 1948 Humboldt University) in Berlin.[1] His doctoral dissertation Über die geistesgeschichtliche Entwicklung des Begriffes der Monarchie (On the History of the Development of the Concept of Monarchy) was completed under the guidance of professor Carl Schmitt. His thesis was later published by the Konrad Tiltsch printing house in Würzburg. In Romania it was published in 1940 under the title Monarhia socială ("Social Monarchy") by Editura Fundației pentru Literatură și Artă Regele Carol II.[citation needed]

Upon returning to Romania after his studies, he became a member of the National Liberal Party (Brătianu).[1] In 1938 he married Pia Pillat, the daughter of poet Ion Pillat and painter Maria Pillat-Brateș, making him brother-in-law of literary critic Dinu Pillat and writer Cornelia Pillat.[citation needed] His wife was the granddaughter of Dinu Brătianu, president of the National Liberal Party.[citation needed]

Beginning of his publishing activity

editIn 1939 he was named editor-in-chief of Rumanian Quarterly magazine owned by the Anglo–Romanian Society. The president of the society was Nicolae Caranfil, with whom Fărcășanu collaborated closely in the Romanian National Committee and the League of Free Romanians.[citation needed] Vice presidents of the society were Zoe Ghețu, George Cretzianu, and Fr. Flow; honorary secretaries were Nicolae Chrissoveloni, Paul Zotta, and Ion Mateescu. The magazine's role was to contribute to the knowledge of cultural values between the two countries and to evidence the spiritual interrelations between the two cultures.[citation needed] The magazine carried articles signed by Romanian personalities such as Nicolae Iorga, Gheorghe Brătianu, Tudor Arghezi, Matila Ghyka, K. H. Zambaccian, Al. O. Teodoreanu, Cella Delavrancea, Militza Pătrașcu and foreign personalities such as Derek Patmore, Henry Baerlein, and journalist Sir Arthur Beverley Baxter. Fărcășanu signed an important essay entitled The Sense of the New Political Regime of Romania. The magazine stopped publishing due to the start of World War II.[citation needed]

In September 1940, he was named president of the National Liberal Youth by Dinu Brătianu. Although the political parties were suspended by Mareșal Ion Antonescu, the National Liberal Party continued its activities, especially its publishing activities.[citation needed] Between 1940 and 1944, Fărcășanu was editor-in-chief of the Românul magazine, worked on the publishing committee of Pământul românesc magazine, and wrote articles in the newspaper Viața Nouă.[citation needed] In 1942 he published the essay Libertate și existență ("Freedom And Existence").[citation needed] In 1943–1944 he was a war correspondent on the Eastern Front. Allegedly he was almost captured by the Soviet Red Army at the bend of the Don River, but managed to flee at the last moment.[citation needed]

After August 23, 1944

editRight after the royal coup of August 23, 1944, the Viitorul newspaper was reborn and Mihail Fărcășanu was appointed editor-in-chief. The organ of the Liberal Party had been banned in 1938 by Carol II of Romania and then by Ion Antonescu.[citation needed] In September 1944, at the proposal of Gheorghe Brătianu, he was reelected as president of the National Liberal Youth. According to his own account, Fărcășanu was the first to criticise Ana Pauker in public, which reportedly stirred a massive communist fightback, calling Fărcășanu an agent of Nazi politician Joseph Goebbels, an enemy of the people and the working class, an adversary of the agriculture reform, and a saboteur of the national industry.[4] He further claimed that when he published in the newspaper the translation of Ernest Hemingway's For Whom the Bell Tolls, the communist press called him a fascist.[4]

In line with the Denazification process taking place in European countries formerly ruled by pro-Nazi regimes, the post-war government took steps to cleanse the police and safety services. Under pressure of the Soviets in the Ceasefire Commission,[5] Nicolae Penescu (Minister of Internal Affairs in the Sănătescu cabinet) and Nicolae Rădescu had to kick out from the two services many agents who had been loyal to the Antonescu dictatorship. These actions were approved by the National Peasants' Party and the National Liberal Party, thinking that this would ensure a more favourable view of Romania from Moscow.[5] Mihail Fărcășanu was a strong opponent of these actions.[5]

In January 1945 Fărcășanu organised Conferința Pregătitoare a Congresului Tineretului Național Liberal (Preparatory Conference of the National Liberal Youth Congress). The conference took place in Sinaia and commemorated 11 years since the assassination of Ion G. Duca and the destruction of the commemorative plaque by the Iron Guard legionnaires.[citation needed] Later that year, Pravda published an article about Mihail Fărcășanu entitled 'Fărcășanu's gang in which PNL and PNȚ stood accused of organizing a demonstration in support General Rădescu, which by the time had a falling-out with the Soviets.[citation needed]

On February 13, 1945, revolting against Rădescu, the communists yelled: Cerem arestarea lui Țețu! ("We want the arrest of Țețu!"), Cerem arestarea lui Fărcășanu! ("We want the arrest of Fărcășanu!").[citation needed] In the later period of Rădescu's government, the communists embarked in a campaign to attract dissident factions of the pre-war political parties, succeeding in bringing several members into the Blocul Partidelor Democrate (BPD, Democratic Bloc of Parties). As a result, the liberal faction led by Gheorghe Tătărescu, and the PNȚ faction led by Anton Alexandrescu joined the communist-led alliance.

The discussions about the attitude of the political parties continued even after the establishment of the Petru Groza government, Romania's first communist-dominated government. Iuliu Maniu proposed that the party maintain the opposition strategy it had adopted in the past, from the period when he was a deputy in Budapest after World War I and even in the time when the parties were legally banned. This point of view was supported by Dinu Brătianu. Fărcășanu wanted to convince them that this would be an error with grave consequences. Fărcășanu said that if they thought the actions of the Communist Party would be suppressed by the Western countries, they were wrong.[citation needed]

In autumn 1945, Fărcășanu participated, as a representative of the National Liberal Youth, in organising a great rally in the Piața Palatului (now Revolution Square, Bucharest), on November 8, the king's birthday.[citation needed] On the last day of 1945 a delegation of the allied powers arrived in Bucharest, led by Archibald Clark Kerr, 1st Baron Inverchapel, W. Averell Harriman and Andrey Januaryevich Vyshinskiy. After the discussion Emil Hațieganu from the Peasants' Party and Mihail Romniceanu from the Liberal Party were assigned to the government as ministers without portfolio.

In February 1946 the two parties were authorised to publish their own works. Because the name Viitorul ("The Future") for the party newspaper was owned by Gheorghe Tătărescu, the liberals decided to call their newspaper Liberalul ("The Liberal"), a name that had used in the past for many newspapers, notably one published in Iași under Nicolae Gane and George G. Mârzescu. Being watched by the authorities, Fărcășanu did not assume the role of editor-in-chief, which was later occupied by Azra Berkowitz.[citation needed] In this period Fărcășanu organised three conferences that had to be held in the grand hall of the Fundației Carol I theater on May 12, 19 and 26, 1945. Inspired by a quote of Dinu Brătianu Libertățile se cuceresc uneori fără jertfe. Dar ele nu se pot menține decât cu jertfe ("Freedom is sometimes gained without sacrifice. But maintaining it calls for sacrifice"), the conferences, where ten associate professors announced their arrival, had the following program:

- I. Cucerirea libertății ("Conquering freedom") – associate professors Mihail Fărcășanu, Dan Amedeu Lăzărescu, Radu Câmpeanu.

- II. Pierderea libertății ("Losing freedom") – associate professors George Fotino, Victor Papacostea, C. C. Zamfirescu.

- III. Recâștigarea libertăţii ("Regaining freedom") – associate professors Alice Voinescu, Paul Dimitriu, Paul Zotta, Mihai Popescu.

At the first talk, after the first words spoken by Fărcășanu, a group of communist activists started a general riot screaming Vi s-au luat moșiile! ("Your estates have been taken away!"). Fărcășanu tried in vain to talk to the agitators. The conference could not take place in a civilised manner, which was seen as a victory for the communists.[6] The Liberal Party's general secretary Dinu Brătianu, who had worked with Teohari Georgescu during the Rădescu government, convinced Fărcășanu to reschedule the conferences to avoid disruption by the communists. On May 19 Fărcășanu managed to organise his first conference, but by the order of the Ministry of the Interior the other two conferences were banned. This was the last time Fărcășanu appeared in a public action in Romania.[citation needed]

In May 1946, the General Police made a report about the National Liberal Party (Dinu Brătianu). The report claimed that Mihail Romniceanu had given a secret order, which was delivered by his secretary Nicolae Magherescu to all the party organisations.[citation needed] This order allegedly said that the Liberal Party should initiate its own secret police to participate in all elections to ensure their proper organisation. The Liberal police would have been run by Fărcășanu. A similar organisation would have been initiated by the Peasants' Party under Corneliu Coposu. These police organisations were never initiated, but because of the General Police report, Fărcășanu had to leave the country to avoid capture.[citation needed]

Flight from Romania

editAware of the fact that his life was at risk if he stayed in Romania, Mihai Fărcășanu made arrangements to flee Romania. He was helped in this endeavor by long-time friend Matei Ghica-Cantacuzino, a fighter pilot who had participated in the military operations in the war against the Soviet Union, reaching Stalingrad, where he took part in the bombing of the railway station on October 5, 1942.[7] Ghica-Cantacuzino had left Romania, but he had returned with the intention of helping close friends escape.

It was agreed that the Fărcășanu family's escape would take place in October 1946, from a small military airport near Caransebeș. The plan was to use an old bomber which had just been repaired and was scheduled to be flown to its base near Brașov. A government commission had just arrived in Caransebeș a day before the flight to inspect the aircraft and to make sure that there were no clandestine passengers on board, and that the aircraft had just enough fuel to fly 300 km (190 mi), the distance between Caransebeș and Brașov.

In agreement with Matei Ghica-Cantacuzino, the mechanic had tampered with the fuel gauge, making it indicate that the tank was only partly full while it was actually completely full. Fărcășanu, his wife Pia, and their friend Vintilă V. Brătianu were hiding in some bushes at the far end of the airfield. The plane started rolling towards the end of the runway having only Ghica-Cantacuzino and the mechanic on board. When the plane reached the end of the runway and turned around for take-off, outside the visibility of the control tower, the three stowaways boarded the plane that was racing its engines, and then took off immediately.

In Yugoslav airspace, the plane was detected by the Yugoslav Air Force, and in took all the skills of the pilot to evade the fighter planes, by flying into the clouds. The plane was, however, hit several times by bullets from the fighters, which took out all the navigation instruments except the altimeter. One of the fuel tanks was also hit. With a damaged plane, having practically no navigation instruments and very limited fuel, the pilot started crossing the Adriatic Sea. They were able to land at military airport in Bari, Italy, with practically empty fuel tanks.

Ivor Porter, who at that time was British SOE and was working at the Embassy of the United Kingdom in Romania, had been informed about the escape attempt. He had sent a cable to the British authorities in Italy requesting them to ensure their protection. He later described the adventure in a book "Operation Autonomous", published in 1989. In his book, he states that if he had not sent such a cable, the escapees might have been sent back to Romania.[8]

The escape has also been described in a novel written by Pia Pillat, Fărcășanu's wife, who was also on the plane. The novel, called "The Flight of Andrei Cosmin", was first published in London in 1972 under the pen name Tina Cosmin, and has been translated into Romanian, being published in Romania in 2002. While it realistically presents the events, she has changed the names of the characters. Thus Mihail Fărcășanu is called Andrei Cosmin, Matei Ghica-Cantacuzino is Ștefan Criveanu, and Ivor Porter is Chris Nelson.[9][10][11]

Activity in exile

editFărcășanu and his wife Pia settled in New York City where they soon became some of the most active members of the Romanian emigrants to the United States. Fărcășanu immediately started a political organization of Romanian refugees. In 1948 he founded the "Council of Romanian Democratic Parties". The Council had the objective of coordinating the activity of the representatives of Romanian political parties outside the Soviet zone of influence and of establishing the Romanian National Committee. Fărcășanu was one of the representatives of the Romanian National Liberal Party in this Council.[12]

Participation in the international European movement

editAfter the end of World War II, the great visionaries of a united Europe, among which Winston Churchill, Jean Monnet, François Mitterrand, Robert Schuman, Altiero Spinelli, Konrad Adenauer, Grigore Gafencu, Alcide de Gasperi, and Paul-Henri Spaak felt the need of an international organism aiming at a unification of the various nations, the respect of human rights and keeping the peace.

On May 7–11, 1948 the 1948 Hague Congress was organized in The Hague, chaired by Winston Churchill. The date was chosen so as to coincide with the third anniversary of the ceasefire which ended World War II in Europe. Following the resolution of this congress, on October 25, 1948 the European Movement International was founded, a nongovernmental organization formed by political personalities from different European countries who were supporting the principle of a united Europe. Romania was represented by Grigore Gafencu, Nicolae Caranfil, Mihail Fărcășanu, and Iancu Zissu, who signed the documents in capacity of founding members.

The Romanian Section of the European Movement was initially headed by Grigore Gafencu, who had remarkable contributions both at the Hague Congress and in the following period. Consequently, for a long time, the section was headed by George Ciorănescu.[13]

Last years

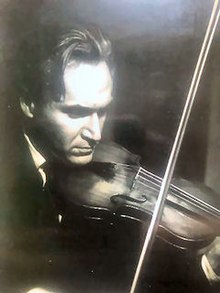

editAfter the death of Louisa Hunnewell Gunther Fărcășanu, Fărcășanu donated the entire holdings of his Franklin Mott Gunther Foundation to the Adormirea Maicii Domnului (Dormition of the Theotokos) Church in Cleveland, Ohio, and to the church's museum. The church was founded on August 15, 1904, as the first Romanian Orthodox church in the United States.[14] He spent the last years of life in his house in the Georgetown district of Washington, D.C., being cared for by his sisters Margareta Bottea and Mia Lahovari and by his niece Domnica Bottea. He had a quiet life playing the violin daily and spending most of his time reading. He met frequently with Constantin Vișoianu, with whom he had collaborated to organise a Romanian resistance in exile. He never tried to write his memoirs or other literary works.

Mihail Fărcășanu died on July 14, 1987, at the age of 79, not long before the fall of the communist regimes in Eastern Europe in 1989.

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f g Şerban Andronescu (April 18, 2007). "Mihail Fărcășanu – Noua Arhivă Românească – revistă on-line de istorie, documente și monografii locale" (in Romanian). Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ Octav-George Lecca (1899). Familiile boiereşti române (in Romanian). Bucharest: Editura Minerva.

- ^ "Foști elevi – evidentiați în diferite domenii" (PDF). www.lahovari.com (in Romanian). Alexandru Lahovari National College. p. 14. Retrieved December 4, 2021.

- ^ a b Cicerone Ionițoiu. "Tombes sans Croix Vol. 1" (in French). Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ a b c Mihai Pelin (September 8, 2005). "Discordiile interne ale opoziţiei după 23 august 1944" (in Romanian). Jurnalul Național. Archived from the original on April 13, 2014. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

- ^ Lăzărescu, Dan Amedeu (2002). Dan Amedeu Lăzărescu (ed.). Anexa I la volumul Scrisori către tineretul român (in Romanian). Vol. 1. Bucharest: Editura Universal Dalsi.

- ^ "Fazekas Zoltan - main". aviatia.cda.ro. Archived from the original on January 7, 2005. Retrieved November 6, 2011.

- ^ Ivor Porter – Operation Autonomous – Ed. Chato and Windus, 1989 (Romanian translation: "Operațiunea Autonomous", Humanitas, București, 1991)

- ^ "Adriana Bittel, pe marginea unei cărţi de Pia Pillat: O poveste adevărată". atelier.liternet.ro.

- ^ http://www.romlit.ro/destinul_soţilor_cosmin[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Romania Culturala". Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved May 30, 2011.

- ^ Ion Calafeteanu – Politică și Exil. Din istoria exilului românesc – Editura Enciclopedică, București 2000

- ^ Mișcarea Europeană – Secțiunea Română

- ^ "100 de ani de la atestarea documentară a comunităţii ortodoxe române din Cleveland" (in Romanian). Timopolis. September 16, 2004. Archived from the original on August 25, 2005. Retrieved January 31, 2009.

Bibliography

edit- Pia Bader Fărcășanu, Izgonirea din libertate. Două destine: Mihail Fărcășanu și fratele sau Nicolae ("Driven Away from Freedom. Two Destinies: Mihail Fărcășanu and His Brother Nicolae"), Institutul Național pentru Memoria Exilului Românesc, Bucharest, 2009.

External links

edit- Media related to Mihail Farcasanu at Wikimedia Commons