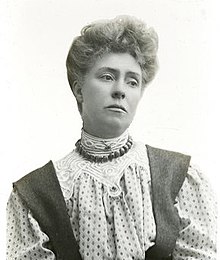

Lucy Minnie Baldock (née Rogers; 20 November 1864[1] – 10 December 1954)[2][3] was a British suffragette.[4] Along with Annie Kenney, she co-founded the first branch in London of the Women's Social and Political Union.[4]

Life and activism

editLucy Minnie Rogers was born in Bromley-by-Bow in 1864. She worked in sweated labour shirt factory and married Harry Baldock in 1888, and they had two children.[5] The East End of London was known for its poor conditions and the Baldocks joined the Independent Labour Party (ILP) after the socialist Keir Hardie became their local Member of Parliament (M.P.) in 1892.[6] She worked with Charlotte Despard and Dora Montefiore.[7] She took charge of the local unemployment Fund that was used to mitigate extreme hardship.[6] Women were not then allowed to be Members of Parliament, but the ILP chose her as their candidate to sit on the West Ham Board of Guardians in 1905.[7]

Baldock and Annie Kenney formed the first London branch (although it was in Canning Town, then in Essex) of the then Manchester based Women's Social and Political Union in 1906, holding meetings at Canning Town Public Hall.[4]

Baldock attended 21 December 1905 pre-election meeting of the Liberals at the Royal Albert Hall dressed as a 'maid' to Annie Kenney (who wore a fur coat) and both sat in a box and Kenney hung a banner over the edge saying 'Votes for Women' and called out, resulting in a disturbance. The next day Baldock visited Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman with Kenney and Teresa Billington to ask about when Liberals would deal with female suffrage, resulting in Dora Montefiore congratulating Baldock's 'noble stand' in a postcard.[6]

Baldock became a paid employee of the WSPU and a mentor to Daisy Parsons,[5] and had a postal order for 30 shillings from Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence to cover the costs of attending meetings in Long Eaton, Derbyshire. Speakers invited to address the Canning Town group included Emmeline Pethick-Lawrence, Annie Kenney and Flora Drummond.[7] Baldock also organised and spoke at an open air meeting in Upton Park.[8] Baldock was arrested on 23 October 1906 (along with Nellie Martel and Anne Cobden Sanderson) for disorderly conduct during the opening of Parliament.[3][9]

In 1907, she reported to the group on her visit to Jane Sbarborough in Holloway Prison when she heard about signalling between suffragettes, imprisoned at the same time, but not allowed to talk to each other. Baldock was also at the prison gate with Christabel Pankhurst to support Flora Drummond and others released to have a celebratory hotel breakfast. She also spoke in June 1907 at a Knightsbridge home event at the request of Louise Eates, Kensington WSPU and in August at a home in Kensington with Emmeline Pankhurst as noted by Sara Jessie Stephenson in her pamphlet No Other Way.[citation needed]

'to make the rich and idle women realise the difficulties that drive poor women to demand the vote'.

In November 1907, Baldock was recording being ejected from a Liberal MP's event on the Isle of Dogs but stood on a chair outside a window calling out "Votes for Women". In summer 1908 she was in Nottingham with Elsa Gye to build up its WSPU. In April 1909 she was with around 500 suffragettes at breakfast in Picadiily for Mrs Pethick-Lawrence's release from custody.[6]

Arrest

editBaldock was with twelve women who were arrested after walking single file through the streets towards the House of Commons with Mrs. Pankhurst in February 1908[10] "to present a petition from the Conference at Caxton Hall, and to the refusal of the authorities to treat suffragist offenders as first-class misdemeanants."[11] Baldock was arrested along with Mrs Pankhurst and others and was charged with resisting and obstructing the police.

"Mrs. Pankhurst, Miss Annie Kenney, and the eight other women suffragists who were arrested on Thursday in attempting to make their way to the Houses of Parliament were yesterday brought before Mr. Horace Smith at the Westminster Police Court. They were charged with resisting and obstructing the police.

...

Miss Kenney and Mrs. Baldock, against whom there were previous convictions, were each fined £5, with the alternative of one month's imprisonment in the second division. Mrs. Pankhurst and the other defendants were each ordered to find sureties of £20 to be of good behaviour for twelve months, or to go to prison for six weeks in the second division. All the ten women chose to go to prison."[11]

Baldock had to leave her two boys with their father whilst she served a month in jail and her fellow suffragettes assisted, including Maud Arncliff Sennett sending toys.[7] Baldock got out a message published in Votes for Women in 1908, that

"I love freedom so dearly that I want all women to have it, and I will fight for it until they get it"[12]

In April that year, Emily Cobb, WSPU, offered to sponsor the cost of a house help so that Baldock could be 'set free to do work you can do [ for the Cause] and many of us can not', and in May Baldock was with Annie Kenney in Bristol, renting a house near the venue Augustine Birrell Liberal MP and Irish secretary of state, was to be speaking at, to help Elsie Howey and Vera Holme who hid overnight in the Hall to get into the event. In October 1909, Baldock was arrested again with Flora Drummond and the Pankhursts back at Clement's Inn.[6]

As a suffragette who had been to jail she was given the honour of planting a commemorative tree at Eagle House in Somerset in February 1909. The house was the home of Mary Blathwayt's parents who supported the cause. Her father took commemorative photographs and afterwards he sent her flower plants in the following April for her garden.[13] The following year, Baldock spoke on Wimbledon Common, and had her travel paid by Minnie Turner, to support Mary Clarke campaigning in Brighton for a week in the summer.[6]

In 1911, she was one of the suffragettes who boycotted the census.[14] Later in 1911, Baldock was diagnosed with cancer and underwent surgery performed by Louisa Aldrich-Blake. Baldock recovered but broke contact with the increasingly militant WSPU. She did keep in contact with Edith How-Martyn and she was still a member of the Church League for Women's Suffrage. At the start of 1913 she and her family had to move to Liverpool for her sons to seek work in shipyards[citation needed], although she and husband were also reported to be in Southampton in 1914.[6]

Baldock took part in Emmeline Pankhurst's funeral, carrying the purple white and green colours (1928) and attended her statue unveiling in 1930. Baldock also supported How-Martyn in documenting the movement in the Suffragette Fellowship.[15]

Posthumous recognition

editBaldock’s name and picture (and those of 58 other women's suffrage supporters) are on the plinth of the statue of Millicent Fawcett in Parliament Square, London, unveiled in 2018.[16][17][18] In 2011, Poole Museum and the National Lottery funds sponsored a short film on Baldock's life called The Right to Vote by Kate O'Malley starring Michelle O'Brien.[19]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ 1939 England and Wales Register

- ^ England & Wales, National Probate Calendar (Index of Wills and Administrations), 1858-1966, 1973-1995

- ^ a b Crawford, Elizabeth (2003). The Women's Suffrage Movement: A Reference Guide 1866-1928. Routledge. pp. 26–27. ISBN 1135434026.

- ^ a b c Jackson, Sarah (12 October 2015). "The suffragettes weren't just white, middle-class women throwing stones". The Guardian. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ a b Awcock, Hannah (10 November 2016). "Turbulent Londoners: Minnie Baldock, c.1864-1954". Turbulent London. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g Diane Atkinson, Diane (8 February 2018). Rise Up Women!: The Remarkable Lives of the Suffragettes. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. pp. 31–2, 45–, 79, 90, 94, 114, 142, 213, 259. ISBN 978-1-4088-4406-9.

- ^ a b c d e "Minnie Baldock". Spartacus Educational. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- ^ "Upton Park Suffragettes Meeting". Stratford Express. 29 September 1906.

- ^ Elizabeth Crawford (2001). The women's suffrage movement: a reference guide, 1866-1928. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-23926-4.

- ^ Purvis, June (2 September 2003). Emmeline Pankhurst: A Biography. Routledge. p. 103. ISBN 9781134341924.

- ^ a b "Mrs Pankhurst in Prison". The Manchester Guardian. 15 February 1908. p. 11. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ^ Votes for Women, 1 March 1908, page 82

- ^ Wilmott Dobbie, B.M. (1979). A Nest of Suffragettes in Somerset. p. 21. ISBN 0950539015.

- ^ "Suffragettes in Canning Town | Newham Heritage Month". www.newhamheritagemonth.org. 9 May 2021. Retrieved 18 November 2024.

- ^ "Museum of London". collections.museumoflondon.org.uk. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- ^ "Historic statue of suffragist leader Millicent Fawcett unveiled in Parliament Square". Gov.uk. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ Topping, Alexandra (24 April 2018). "First statue of a woman in Parliament Square unveiled". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 April 2018.

- ^ "Millicent Fawcett statue unveiling: the women and men whose names will be on the plinth". iNews. 24 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "The Right to Vote (short movie)". YouTube. 2011. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

External links

editMedia related to Minnie Baldock at Wikimedia Commons