This article may require copy editing for grammar, style, cohesion, tone, or spelling. (June 2024) |

Ishida Mitsunari (石田 三成, 1559 – November 6, 1600) was a Japanese samurai and military commander of the late Sengoku period of Japan. He is probably best remembered as the commander of the Western army in the Battle of Sekigahara following the Azuchi–Momoyama period of the 16th century. He is also known by his court title, Jibu-no-shō (治部少輔).

Ishida Mitsunari | |

|---|---|

| 石田 三成 | |

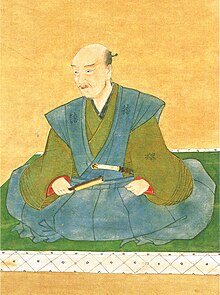

Ishida Mitsunari, depicted in a portrait. | |

| Daimyō of Sawayama Castle | |

| In office 1590–1600 | |

| Succeeded by | Ii Naomasa |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Sakichi (佐吉) 1559 Ōmi Province (present-day Nagahama, Shiga Prefecture) |

| Died | November 6, 1600 (aged 40–41) Kyoto |

| Resting place | Sangen-in, Daitoku-ji, Kyoto |

| Spouse | Kogetsu-in |

| Children | Ishida Shigeie Ishida Shigenari Ishida Sakichi Tatsuhime at least two other daughters |

| Parents |

|

| Relatives | Ishida Masazumi (brother) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | |

| Rank | Bugyō, Daimyō |

| Commands | Sawayama Castle |

| Battles/wars | Siege of Tottori Siege of Takamatsu Battle of Shizugatake Battle of Komaki and Nagakute Siege of Oshi Korean Campaign Siege of Fushimi Battle of Sekigahara |

Biography

editMitsunari was born in 1559 at the north of Ōmi Province (which is now Nagahama city, Shiga Prefecture), and was the second son of Ishida Masatsugu, who was a retainer for the Azai clan. His childhood name was Sakichi (佐吉). The Ishida withdrew from service after the Azai's defeat in 1573 at the Siege of Odani Castle. According to legend, he was a monk in a Buddhist temple before he served Toyotomi Hideyoshi, but the accuracy of this legend is doubted since it only came about during the Edo period.[citation needed]

In 1577, Mitsunari met Toyotomi Hideyoshi, when the former was still young and the latter was the daimyō of Nagahama. Later, Mitsunari became a Hideyoshi samurai officer. When Hideyoshi engaged in a campaign in the Chūgoku region, Mitsunari assisted his lord in attacks against castles like the Tottori Castle and Takamatsu Castle (in present-day Okayama).[citation needed]

In 1583, Mitsunari participated in the Battle of Shizugatake. According to the "Hitotsuyanagi Kaki", he was in charge of a mission to spy on Shibata Katsuie's army and also performed a great feat of Ichiban-yari (being the first to thrust a spear at an enemy soldier) as one of the warriors on the front line. Later, he served in the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute in 1584. That same year, he worked as a kenchi (survey magistrate) at Gamo county in Omi Province.[citation needed]

In 1585, Mitsunari was appointed as administrator of Sakai, a role he took together with his elder brother Ishida Masazumi. He was appointed one of the five bugyō, or top administrators of Hideyoshi's government, along with Asano Nagamasa, Maeda Gen'i, Mashita Nagamori and Natsuka Masaie. Hideyoshi made him a daimyō of Sawayama in Ōmi Province, a five hundred thousand koku fief (now a part of Hikone). Sawayama Castle was known as one of the best-fortified castles during that time. In January 1586, he hired Shima Sakon, who was renowned as a commander having wisdom and courage.[citation needed]

In 1588, Mitsunari was placed in charge of the famed “sword hunt” conducted by Hideyoshi in an effort to disarm the non-military bulk of the population and preserve peace.[citation needed]

In 1590 campaign against the Hōjō clan, where he commanded the Siege of Oshi and captured Oshi Castle.[1][2]

In 1592, Mitsunari was participated in the Japanese invasions of Korea as one of the Three Bureaucrats with Mashita Nagamori and Asano Nagamasa.[1]

In 1597, Mitsunari was ordered by Hideyoshi to persecute Christians. However, he showed sympathy to Christianity by minimising the number of Christians he arrested, and trying hard to appease Hideyoshi's anger (see 26 Martyrs of Japan). In the same year, Mitsunari also reportedly working to end the war with Korea and China.[3]

Sekigahara Campaign and death

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2024) |

Mitsunari had high status among the bureaucrats of Hideyoshi's government, and was known for his unbending character. He had many friends; two of the most notable being the famous samurai Ōtani Yoshitsugu and Shima Sakon. However, Mitsunari was on bad terms with some daimyō that were known as good warriors, including Kuroda Nagamasa and Hachisuka Iemasa, as well as Hideyoshi's nephew Kobayakawa Hideaki. In particular, Kobayakawa Hideaki developed a grudge against Mitsunari as a result of rumors spread by Tokugawa Ieyasu that Mitsunari was behind his uncle's decision not to reward him with Chikugo after Kobayakawa's reckless behaviour at the Siege of Ulsan. Toward the end of Taiko Hideyoshi's life, Hideyoshi ordered the execution of his heir and nephew Toyotomi Hidetsugu and Hidetsugu's family, leaving his new heir to be the extremely young child, Toyotomi Hideyori.[citation needed]

After Hideyoshi's death, the conflicts in the court worsened. The central point of the conflict was the question of whether Tokugawa Ieyasu could be relied on as a supporter of the Toyotomi government, whose nominal lord was still a child, with actual leadership falling to a council of regents. After the death of the respected "neutral" Maeda Toshiie in 1599, the conflict came to arms, with Mitsunari forming an alliance of Toyotomi loyalists to stand against Tokugawa Ieyasu. Mitsunari's support came largely from the three of Hideyoshi's regents: Ukita Hideie, Mōri Terumoto, and Uesugi Kagekatsu, who came from the south and west of Japan, with the addition of the Uesugi clan in the north. Tokugawa Ieyasu's support came from central and eastern Japan, but he still exercised influence and intimidation over some of the Western lords. The titular head of the Western alliance was Mōri Terumoto, but Mōri stayed entrenched in Osaka castle; the leadership fell to Mitsunari in the field.

In mid 1600, the campaign began. Mitsunari besieged Fushimi Castle before marching into direct conflict with Tokugawa's alliance at Sekigahara. In October 21, at the Battle of Sekigahara, a number of lords stayed neutral, watching the battle from afar, not wishing to join in the losing side. Tokugawa's forces gained the edge in the battle with the betrayal of Kobayakawa Hideaki to their side, and won the battle.

After his defeat at Sekigahara, Mitsunari sought to escape but was caught by villagers. He was beheaded in Kyoto. Other daimyō of the Western army, like Konishi Yukinaga and Ankokuji Ekei were also executed. After execution, his head, severed from his body, was placed on a stand for all the people in Kyoto to see. His remains were buried at Sangen-in, a sub-temple of the Daitoku-ji, Kyoto.[citation needed]

A legend says that Ieyasu showed him mercy but hid him, for political reasons, with one of his veteran generals, Sakakibara Yasumasa, where he grew old and died of natural causes. To thank Yasumasa for his silence, Mitsunari gave him a tantō nicknamed Ishida Sadamune (石田貞宗) – a National Treasure of Japan.[citation needed]

Personal life

editMitsunari had three sons (Shigeie, Shigenari, and Sakichi) and three daughters (only the younger girl's name is known, Tatsuhime) with his wife. After his father's death, Shigenari changed his family name to Sugiyama to keep living.[citation needed]

Sawayama Castle was a castle which was controlled by the Ishida clan. When the castle captured by the Eastern army after the Sekigahara battle ended and after Mitsunari died, it was reported by a Tokugawa vassal named Itasaka Bokusai who entered the castle that there was not a single piece of gold or silver kept by Ishida Mitsunari there.[4]

Mitsunari as military commander

editAccording to Asano clan Documents, there is popular belief that Mitsunari's reputation as military commander were suffered badly due to the alleged bad performance during the Siege of Oshi, particularly his failed strategy to flood the castle to force the defender to submit.[a] However, other records based on documented correspondence of the operation have stated that the water flooding attack was actually an instruction from Toyotomi Hideyoshi himself, which was relayed by Asano Nagamasa and Kimura Shigekore, while Mitsunari only executed the strategy and actually did not have freedom to devise his own initiatives.[5]

Stephen Turnbull stated that traditional Japanese historiography did not pay much attention to Mitsunari's legacy, as he lost and Tokugawa won; he was often portrayed as a weak bureaucrat. His reputation has somewhat recovered since then, with later historians note his skill in planning and earlier battlefield victories, and that Sekigahara could easily have gone his way had a few more lords remained loyal.[1]

Conflict with military faction

editAccording to popular theory, in 1598, after the death of Toyotomi Hideyoshi, the government of Japan had an accident when seven military generals consisting of Fukushima Masanori, Katō Kiyomasa, Ikeda Terumasa, Hosokawa Tadaoki, Asano Yoshinaga, Katō Yoshiaki, and Kuroda Nagamasa planned a conspiracy to kill Ishida Mitsunari.[6] However, despite the traditional depiction of the event as "seven generals against Mitsunari", modern historian Watanabe Daimon has pointed out that actually there were more generals involved in conflict against Mitsunari, such as Hachisuka Iemasa, Tōdō Takatora, and Kuroda Yoshitaka who also brought their troops and entourage to confront Mitsunari.[7]

It was said that the reason behind this conspiracy was dissatisfaction of those generals towards Mitsunari as he wrote poor assessments and underreported their achievements during the Japanese invasions of Korea,[6] while some like Tadaoki also accused Mitsunari of other mismanagement during his tenure under Hideyoshi.[7] At first, these generals gathered at Kiyomasa's mansion in Osaka Castle, and from there they marched to Mitsunari's mansion. However, Mitsunari had learned of this from a report by a servant of Toyotomi Hideyori named Jiemon Kuwajima, and fled to Satake Yoshinobu's mansion together with Shima Sakon and others to hide.[6] When the seven generals found out that Mitsunari was not in his mansion, they searched the mansions of various feudal lords in Osaka Castle, and Kato's army also approached the Satake residence. Mitsunari and his party escaped from the Satake residence and barricaded themselves at Fushimi Castle.[8] The next day, the seven generals surrounded Fushimi Castle with their soldiers as they knew Mitsunari was hiding there. Tokugawa Ieyasu, who was in charge of political affairs in Fushimi Castle attempted to arbitrate the situation. The seven generals requested Ieyasu to hand over Mitsunari, which Ieyasu refused. Ieyasu then negotiated a promise to let Mitsunari retire and to review the assessment of the Battle of Ulsan Castle in Korea which had been a major source of this incident. He also had his second son, Yūki Hideyasu, to escort Mitsunari to Sawayama Castle.[9]

However, historians like Daimon, Junji Mitsunari, and Goki Mizuno have pointed out from the primary and secondary sources text about the accident that this was more of legal conflict between those generals and Mitsunari, rather than conspiracy to assassinate him. The role of Ieyasu here was not to physically protect Mitsunari from physical harm, but to mediate the legal complaints from the military faction figures who had a problem with Mitsunari. Considering these facts, a more proper term to describe this incident is "the military generals' lawsuit against Mitsunari", rather than "Seven generals' conspiracy to kill Mitsunari".[10][7]

Nevertheless, historians viewed this incident not just as simply personal problems between those generals and Mitsunari, but rather as an extension of the political rivalries of greater scope between the Tokugawa faction and the anti-Tokugawa faction led by Mitsunari. Since this incident, those military figures who were on bad terms with Mitsunari would later support Ieyasu during the conflict of Sekigahara between the Eastern army led by Tokugawa Ieyasu and the Western army led by Ishida Mitsunari.[6][11] Muramatsu Shunkichi, writer of "The Surprising Colors and Desires of the Heroes of Japanese History and violent women”, gave his assessment that the reason of Mitsunari failed in his war against Ieyasu was due to his unpopularity among the major political figures of that time.[12]

Political rivalry with Ieyasu

editFor long time, the prevailing opinion about the cause of the Sekigahara war between Mitsunari and Ieyasu was that it was caused by the enmity between them. However, this view was challenged by Tonooka Shin'ichirō, a professor at Nara University and director of the Tsuruga City museum, as Shin'ichirō viewed the political maneuvers which led to the conflict in Sekigahara as being solely based on Mitsunari's motivation to regain his political position after the coup of military factions which stripped him of his position and had nothing to do with Ieyasu at personal level.[13]

Legacy

editOn May 19, 1907, a group of Japanese researchers planned an excavation of Mitsunari's grave with the cooperation of a local newspaper. This was meant to aid Sesuke Watanabe from Tokyo Imperial University, who was writing a biography on Mitsunari. The one who led and examined the remains of Mitsunari was archaeologist Buntarō Adachi. Adachi restored Mitsunari's damaged skull, made a plaster cast, and recorded measurements of his upper arm bone and other bones. In 1943, a student of Adachi, Kenji Seino took further investigation, relying on photographs of Mitsunari's remains to conduct interviews with Adachi. When Seino completed his investigation, he discovered that Mitsunari's head was long from front to back and he had crooked teeth, and it was estimated that Mitsunari's age at the time of his death was about 41. Furthermore, Seino had reported his finding that based on the skeleton, it was difficult to distinguish the skeleton's gender. Seino also reported that the height of Mitsunari was estimated to be 156 centimeters. After the investigation, a plaster statue and other specimens of Mitsunari were preserved at Kyoto Imperial University, and his remains were reburied.[14]

The katana nicknamed Ishida Masamune, made by the master swordsmith Masamune, was formerly owned by Ishida Mitsunari. It is an Important Cultural Property according to the Agency for Cultural Affairs, and is held in the Tokyo National Museum.

The Tantō "Hyūga Masamune", also made by Masamune, was also in the possession of Ishida Mitsunari. He gave this sword to Fukuhara Nagatake [the husband of his younger sister]; the sword was taken by Eastern army general named Mizuno Katsushige after the Western army defeated battle of Sekigahara.[15] It is a National Treasure of Japan, and is currently held in the Mitsui Memorial Museum.[citation needed]

Popular culture

edit- In James Clavell's novel Shōgun, the character of "Ishido" is based on the historical figure Ishida. In the 1980 TV mini-series adaptation, Ishido was portrayed by Nobuo Kaneko. The character is played by Takehiro Hira in the 2024 adaptation, Shōgun.[16]

- Mitsunari appears in the 1989 film Rikyu by Hiroshi Teshigahara.

- In the 2017 film Sekigahara, Mitsunari is the main character and is portrayed quite sympathetically. This version of Mitsunari is dismayed at Hideyoshi's execution of his heir and regent, recruits allies interested in ruling with justice, is uncomfortable with taking families hostage as leverage, genuinely seeks the best for Hideyoshi's heir, and is in general a forthright and honest type. His rival Tokugawa is portrayed as more of a schemer. The director, Masato Harada, saw Mitsunari as a more modern type of ruler, ahead of his time.

- Mitsunari is a character in the Sengoku Basara franchise where he is portrayed more as a warrior loyal to Hideyoshi as opposed to an administrator and a general. He excels in using Iaido and darkness-based attacks there. In one anime he hates Ieyasu Tokugawa but in the other Ieyasu hated him, while in movie he hated Masamune Date more than Ieyasu. Mitsunari is voiced by Tomokazu Seki in all Japanese media. Troy Baker voiced him in English with the exception of End of Judgement, where he is replaced by Matthew Mercer.

- In the Samurai Warriors video game series, Mitsunari is portrayed as a strategist of the Toyotomi forces against the Hōjō clan, using a fan in battle.

- Mitsunari is a playable character in Pokémon Conquest (Pokémon + Nobunaga's Ambition in Japan), with his partner Pokémon being Pawniard and Bisharp.

- In Nioh, a game based on the events of the late Sengoku period, Ishida is featured as a strategist under the Toyotomi clan. After losing the Battle of Sekigahara, Mitsunari is betrayed by the antagonist Edward Kelley, an English alchemist, and transformed into a yokai (demon) by him. The protagonist William Adams must then fight the transformed Mitsunari in a boss battle.

- Mitsunari is also a suitor in the Japanese romance game Ikemen Sengoku where he is viewed as an innocent angel who adores Ieyasu. However, his adoration is often rebuked.

- The manga Lone Wolf and Cub has the eponymous Lone Wolf tell Daigoro that Mitsunari, after being sentenced to death, was given a persimmon but refused to eat it on the grounds that persimmons made him sick. He was supposedly mocked for caring about indigestion when he was about to be executed, but Lone Wolf tells Daigoro that Mitsunari did the right thing by preserving his health until the last moment so he could fight for his lord.

Appendix

editFootnotes

edit- ^ 大日本古文書 浅野家文書』21号文書

References

edit- ^ a b c Turnbull, Stephen (2012). Tokugawa Ieyasu. Bloomsbury. ISBN 9781849085755.[page needed]

- ^ Turnbull, Stephen (1998). The Samurai Sourcebook. London: Cassell & Co. p. 241. ISBN 9781854095237.

- ^ Kenshiro Kawanishi (川西賢志郎) (2023). "井伊直政の「特別扱い」(上)有能で苛烈な忠臣筆頭" [Naomasa Ii's "Special Treatment" (upper) Treatment of a competent and intense loyalty part 1]. Sankei online (in Japanese). The Sankei Shimbun. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

Interview with Ōta kōji, Former director of Nagahama Castle Historical Museum and Ishida Mitsunari's history researcher

- ^ Kondō Heijō (1907). 史籍集覧 25改定 (in Japanese). Tokyo: 近藤出版部. p. 66. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Nakano Anai (2016). 石田三成伝. 吉川弘文館. p. 114. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ a b c d Mizuno Goki (2013). "前田利家の死と石田三成襲撃事件" [Death of Toshiie Maeda and attack on Mitsunari Ishida]. 政治経済史学 (in Japanese) (557号): 1–27.

- ^ a b c Watanabe Daimon (2023). ""Ishida Mitsunari Attack Incident" No attack occurred? What happened to the seven warlords who planned it, and Ieyasu?". rekishikaido (in Japanese). PHP Online. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 11 June 2024.

- ^ Kasaya Kazuhiko (2000). "豊臣七将の石田三成襲撃事件―歴史認識形成のメカニズムとその陥穽―" [Seven Toyotomi Generals' Attack on Ishida Mitsunari - Mechanism of formation of historical perception and its downfall]. 日本研究 (in Japanese) (22集).

- ^ Kasaya Kazuhiko (2000). "徳川家康の人情と決断―三成"隠匿"の顚末とその意義―" [Tokugawa Ieyasu's humanity and decisions - The story of Mitsunari's "concealment" and its significance]. 大日光 (70号).

- ^ "七将に襲撃された石田三成が徳川家康に助けを求めたというのは誤りだった". yahoo.co.jp/expert/articles/ (in Japanese). 渡邊大門 無断転載を禁じます。 © LY Corporation. Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Mizuno Goki (2016). "石田三成襲撃事件の真相とは". In Watanabe Daimon (ed.). 戦国史の俗説を覆す [What is the truth behind the Ishida Mitsunari attack?] (in Japanese). 柏書房.

- ^ 歴代文化皇國史大觀 [Overview of history of past cultural empires] (in Japanese). Japan: Oriental Cultural Association. 1934. p. 592. Retrieved 23 May 2024.

- ^ Tonooka Shin'ichirō (外岡慎一郎) (2023). "関ケ原の敗因「準備不足」 石田三成祭で奈良大・外岡教授が講演" [Sekigahara's defeat "Under preparation" Professor Nara University and Professor Tonooka gave a lecture at the Ishida Mitsunari Festival]. Sankei online (in Japanese). The Sankei Shimbun. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ Watanabe Daimon (2023). "墓から掘り起こされ、調査された石田三成の遺骸". yahoo.co.jp/expert (in Japanese). Retrieved 2 June 2024.

- ^ Jizaemon, Fuji, ed. (1979). 関ヶ原合戦史料集 [Sekigahara Battle Historical Materials Collection] (in Japanese). 新人物往来社. p. 421. Retrieved 22 May 2024.

- ^ "Takehiro Hira as Ishido Kazunari". FX Networks. Retrieved 2024-04-14.

Bibliography

edit- Bryant, Anthony. Sekigahara 1600: The Final Struggle for Power. Praeger Publishers, 2005

- SengokuDaimyo.com The website of Samurai Author and Historian Anthony J. Bryant

- SamuraiArchives.com Archived 2007-04-02 at the Wayback Machine