The mountain bluebird (Sialia currucoides) is a migratory small thrush that is found in mountainous districts of western North America. It has a light underbelly and black eyes. Adult males have thin bills and are bright turquoise-blue and somewhat lighter underneath. Adult females have duller blue wings and tail, grey breast, grey crown, throat and back. In fresh fall plumage, the female's throat and breast are tinged with red-orange which is brownish near the flank, contrasting with white tail underparts. Their call is a thin 'few' while their song is a warbled high 'chur chur'. The mountain bluebird is the state bird of Idaho and Nevada. This bird is an omnivore and it can live 6 to 10 years in the wild. It eats spiders, grasshoppers, flies and other insects, and small fruits. The mountain bluebird is a relative of the eastern and western bluebirds.

| Mountain bluebird | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Passeriformes |

| Family: | Turdidae |

| Genus: | Sialia |

| Species: | S. currucoides

|

| Binomial name | |

| Sialia currucoides (Bechstein, 1798)

| |

| |

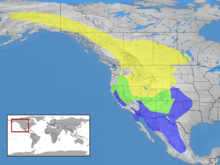

Breeding range Year-round range Wintering range

| |

| Synonyms | |

Taxonomy

editThe mountain bluebird was formally described in 1798 by the German ornithologist Johann Matthäus Bechstein and given the name Motacilla s. Sylvia currucoides.[4][5] The specific epithet combines curruca, from Carl Linnaeus's binomial name Motacilla curruca for the lesser whitethroat with the Ancient Greek -oidēs meaning "resembling".[6] The mountain bluebird is now placed with the two other bluebirds in the genus Sialia that was introduced by the English naturalist William John Swainson in 1827.[7][8] The species is monotypic: no subspecies are recognised.[8]

Description

editThe mountain bluebird is 15.5–18 cm (6.1–7.1 in) in length, weighs 24–37 g (0.85–1.31 oz), and has a wingspan of 11.0-14.2 in (28-36 cm).[9] It is sexually dimorphic in the color of the plumage but the sexes are similar in size. An adult male is bright turquoise-blue above and somewhat lighter blue underneath but with a white lower belly. An adult female has duller blue wings and tail, grey breast, grey crown, throat and back. In fresh fall plumage, the female's throat and breast are brownish near the flank, contrasting with white tail underparts.[10] Their call is a thin 'few'; while their song is warbled high 'chur chur'.

Distribution and habitat

editTheir breeding habitat is open country across western North America, including mountainous areas, as far north as Alaska. Although mountain bluebirds can be found in some states year-round, their range is expansive — they generally migrate south to Mexico in the winter and north into western Canada and even Alaska in the summer. Depending on the time of year, they may be ubiquitous in mountain environments like grasslands or landscapes of sagebrush, where trees and shrubs are fairly spread out.[11]

Behavior and ecology

editBreeding

editThe male can be seen singing from bare branches. The singing takes place right at dawn, just when the sun rises.

Mountain bluebirds nest in pre-existing cavities or in nest boxes. In remote areas, these birds are less affected by competition for natural nesting locations than other bluebirds. Mountain bluebirds are monogamous. After the couple decides together on an ideal nesting site, the female will typically build their nest themselves out of thin, dry material from the surrounding landscape while the male protects the area, defending against unwelcome visitors. It is true, though, that both males and females fiercely protect the nest. Once the nest is built, the female will lay an egg a day. Eggs are pale blue and unmarked, sometimes white. The clutch size is four or five eggs and she will incubate them for about two weeks. Young are naked and helpless at hatching and may have some down. The young will usually take about 21 days before they leave the nest, and it can take up to two months to raise fledglings to a stage of development at which they are able to fend and provide for themselves.[12]

Mountain bluebirds are cavity nesters and can become very partial to a nest box, especially if they have successfully raised a clutch. They may even reuse the same nest, though not always. These birds will not abandon a nest if human activity is detected close by or at the nest. Because of this, they can be easily banded while they are still in the nest. The threats of predation for those that dwell in nesting boxes are mostly from house cats, raccoons, and the parasitic blowfly, Apaulina stalia.[12]

Feeding

editDuring the summer, the diet of Mountain bluebirds predominately consists of insects; while, in the winter months they eat mostly berries (like Juniper berries, Russian-olive berries, elderberry, etc.) and fruit seeds (such as mistletoe seeds and grapes, just to name a few).[13] These birds hover over the ground and fly down to catch insects, also flying from a perch to catch them. The first technique takes up to 8 times the energy of sitting on a perch and waiting. They may forage in flocks in winter, looking for grasshoppers. Mountain Bluebirds will come to a platform feeder with live meal worms, berries, or peanuts.

Relationship to humans

editThe mountain bluebird is the state bird of Idaho and Nevada.[14][15] More generally, the bluebird has lived in writers' and poets' imaginations as age-old bearers of joy and reverie.[12] The Twitter bird was based on the mountain bluebird.[16]

Conservation status

editMountain bluebirds are fairly common, but populations declined by about 26% between 1966 and 2014, according to the North American Breeding Bird Survey. Partners in Flight estimates the global breeding population of 4.6 million, with 80% spending some part of the year in the U.S., 20% breeding in Canada, and 31% wintering in Mexico. The species rates an 8 out of 20 on the Continental Concern Score. Mountain Bluebird is a U.S.-Canada Stewardship species, and is not on the 2014 State of the Birds Watch List. These bluebirds benefited from the westward spread of logging and grazing in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when the clearing of forest created open habitat for foraging. The subsequent waning of these industries, coupled with the deliberate suppression of wildfires, led to a dwindling of open acreage in the West and the decline of the species. More recently, as land-use practices have stabilized, so have Mountain Bluebird populations. Construction of nest boxes in suitable habitat has also provided a population boost. Populations are declining in areas where trees are too small to provide natural nesting cavities, and where forest and agricultural management practices have reduced the availability of suitable nest sites. Among birds that nest in cavities but cannot excavate them on their own, competition is high for nest sites. Mountain, Western, and more recently Eastern bluebirds compete for nest boxes where their ranges overlap. House Sparrows, European Starlings, and House Wrens also compete fiercely with bluebirds for nest cavities.[17]

Industrial noise from natural gas wells can have a negative effect on breeding mountain bluebirds. When mountain bluebirds were exposed to this noise, it caused decreased baseline corticosterone levels in adults and nestlings, increased acute (stress-induced) corticosterone levels, and reduced fitness.[18] The combined effect of decreased baseline and increased acute corticosterone may reduce the fitness of these birds by making them susceptible to inflammation and disease.[18] Another study found that when nest boxes were set up in areas near industrial noise and in quiet control areas, there was a lower occupancy of the mountain bluebird at noisy sites, presumably because the noise reduces hatching success.[19] Hatching success may be reduced in noisy areas as a result of increased distraction and increased vigilance behavior by females. Female bluebirds that leave the nest more frequently expose their eggs to fluctuations in incubation time and temperature. This increases predation risk of these eggs and reduces incubation time, resulting in fewer eggs successfully hatching.[18][19]

Similar species

edit- Western bluebird (Sialia mexicana)

- Eastern bluebird (Sialia sialis)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ BirdLife International (2019). "Sialia currucoides". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2019: e.T22708556A137560639. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2019-3.RLTS.T22708556A137560639.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ Swainson, William John; Richardson, J. (1831). Fauna boreali-americana, or, The zoology of the northern parts of British America. Vol. Part 2. The Birds. London: J. Murray. p. 209. The title page bears the year 1831 but the volume did not appear until 1832.

- ^ Lepage, Denis. "Mountain Bluebird". Avibase. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ Latham, John; Bechstein, Johann Matthäus (1798). Johann Lathams allgemeine Uebersicht der Vögel (in German). Vol. 3, Part 2. Nürnberg: A.C. Weigels and Schneiders. p. 546.

- ^ Mayr, Ernst; Paynter, Raymond A. Jr, eds. (1964). Check-List of Birds of the World. Vol. 10. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Museum of Comparative Zoology. p. 85.

- ^ Jobling, James A. (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. p. 125. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- ^ Swainson, William John (1827). "A synopsis of the birds discovered in Mexico by W. Bullock, F.L.S. and Mr. William Bullock jun". Philosophical Magazine. New Series. 1: 364–369 [369]. doi:10.1080/14786442708674330.

- ^ a b Gill, Frank; Donsker, David; Rasmussen, Pamela, eds. (2020). "Thrushes". IOC World Bird List Version 10.2. International Ornithologists' Union. Retrieved 10 September 2020.

- ^ "Mountain Bluebird Identification, All About Birds, Cornell Lab of Ornithology". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2020-09-29.

- ^ Johnson, L. Scott; Dawson, Russell D. (2020). Rodewald, P.G. (ed.). "Mountain Bluebird (Sialia currucoides), version 1.0". Birds of the World. Ithaca, NY, USA: Cornell Lab of Ornithology. doi:10.2173/bow.moublu.01. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ Sibley, David Allen (2016). Sibley Birds West. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 344. ISBN 978-0-307-95792-4.

- ^ a b c Scott, Lorne (1996). "Mountain Bluebird" (PDF). Canadian Wildlife Service: 1–4 – via OskiCat.

- ^ Burnett, Kassidy; Fair, Jeanne M. (2008). "Winter feeding habits of the mountain bluebird (Sialia currucoides) in northern New Mexico". United States Department of Energy. OSTI 964973 – via EBSCOhost.

- ^ "Idaho State Bird". Georgia State Bird Mountain Bluebird Sialia currucoides. Netstate.

- ^ "Nevada State Bird". Nevada State Bird, mountain bluebird. Val-U-Corp Services, Inc. Archived from the original on 2012-02-29. Retrieved 2014-07-31.

- ^ Rehak, Melanie (8 August 2014). "Who Made That Twitter Bird?". New York Times.

- ^ "Mountain Bluebird". www.allaboutbirds.org. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

- ^ a b c "Correction for Kleist et al., Chronic anthropogenic noise disrupts glucocorticoid signaling and has multiple effects on fitness in an avian community". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 115 (9): E2145. 2018-02-20. Bibcode:2018PNAS..115E2145.. doi:10.1073/pnas.1801328115. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 5834744. PMID 29463740.

- ^ a b Kleist, Nathan J.; Guralnick, Robert P.; Cruz, Alexander; Francis, Clinton D. (January 2017). "Sound settlement: noise surpasses land cover in explaining breeding habitat selection of secondary cavity-nesting birds". Ecological Applications. 27 (1): 260–273. Bibcode:2017EcoAp..27..260K. doi:10.1002/eap.1437. ISSN 1051-0761. PMID 28052511.

- All About Birds: Mountain Bluebird, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Further reading

edit- Herlugson, Christopher J. (1981). "Nest site selection in mountain bluebirds" (PDF). Condor. 83 (3): 252–255. doi:10.2307/1367317. JSTOR 1367317.

- Ridgway, Robert (1907). "The Birds of North and Middle America, Part IV". Bulletin of the United States National Museum. 50. Washington: Government Printing Office: 156–159. ISSN 0096-2961. LCCN sf83008059. OCLC 7347186. Retrieved 2023-11-19.