The Munich-Neuaubing repair plants (abbreviated to AW München-Neuaubing) was a railroad repair works in the west of the Bavarian Bavarian capital Munich in today's Aubing district.

The Königlich Bayerische Staatseisenbahnen opened the plant in 1906 as the Centralwerkstätte Aubing with two repair halls. It was extended several times in the following years. By 1927, the Deutsche Reichsbahn had built a third wagon repair workshop. While the plant was opened as a goods wagon repair workshop, it was later used primarily for the maintenance of passenger carriages. In addition, railcars and occasionally electric locomotives were repaired. The Deutsche Bahn shut it down at the end of 2001. Large parts of the former workshop buildings are now under listed building protection.

Location

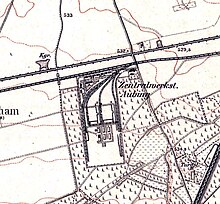

editThe Munich-Neuaubing repair plant is located in the southwest of the Neuaubing district in the Munich borough of Aubing-Lochhausen-Langwied, south of the Munich-Pasing-Herrsching railroad line and the Munich-Neuaubing railroad station and west of Brunhamstraße. The former railroad workers' housing estate, the Neuaubing Colony, is located to the northeast of the factory premises between the workshops and the railroad line on Papinstraße. To the west, the factory site is bordered by the sports facilities of the Eisenbahnersportverein Neuaubing to the north and the derelict site of a former switch depot to the south, with the Freiham district, which has been under construction since 2006, bordering to the west. To the south is a wooded area in which the Bundesautobahn 96 (A 96) runs through, adjoins the repair plant. To the east of the plant area is a residential area, the south-east corner of the plant site is directly on the city limits of the Gräfelfing district of Lochham.[1]

About 300 meters to the east, directly south of the Munich-Pasing-Herrsching railroad line, but on the other side of Brunhamstraße, was the Ausbesserungswerk of the Compagnie Internationale des Wagons-Lits, which was later operated by the Deutsche Schlafwagen- und Speisewagengesellschaft and closed in 1999.[1]

The access tracks to the Neuaubing repair works branched off from the Munich-Pasing-Herrsching railroad line east of the Brunhamstraße level crossing and crossed Brunhamstraße together with the Herrsching line. They then led south past the station building of Neuaubing station to the access gate of the plant. Directly in front of the access gate, Papinstraße crossed the access tracks.[2]

Name

editDuring its existence, the repair plant changed names several times.[3]

| Period | Designation |

|---|---|

| 1906–1915 | Central workshop in Aubing |

| 1915–1920 | Central workshop Neuaubing |

| 1920–1924 | Neuaubing main workshop |

| 1924 | Neuaubing railroad repair works |

| 1924–1942 | Reichsbahn repair works Neuaubing |

| 1942–1948 | Reichsbahn repair works Munich-Neuaubing |

| 1948–1951 | Munich-Neuaubing railroad repair works |

| 1951–2001 | Munich-Neuaubing repair plant |

History

editConstruction and operation until the First World War

editOn February 24, 1900, the Bavarian government passed the law to establish the V. Centralwerkstätte der königlich bayerischen Staatsbahn. The construction costs were set at 5,969,000 marks. The Bavarian State Railways purchased the building land in 1901 and began construction of the workshop in Aubing on March 4, 1902. To this end, the woodland on the building site was first cleared in 1902. Extensive earthworks were necessary to level the site to the level of the Pasing-Herrsching railroad line, lowering it by up to 2+1⁄2 meters. On July 1, 1903, the Bavarian State Railways opened the Pasing-Herrsching local line running north past the factory site with the Freiham station requested by Maffei. At the junction of the access tracks to the Centralwerkstätte from the Pasing-Herrsching line, the separate stop Zentralwerkstätte Aubing was opened on November 20, 1905, which was given the name Neuaubing on October 1, 1908.[4]

On October 1, 1906, the Royal Bavarian State Railways officially put the Centralwerkstätte Aubing into operation.[5] The repair of freight wagons was partly relocated from the Centralwerkstätte München to Aubing and from then on carried out by both workshops in a division of labor. At the time of opening, there were two wagon repair workshops with a total of 250 stalls, an administration building, a forge and a woodworking facility as well as other warehouses and a water house. The Aubing plant employed 160 workers and nine civil servants, for whom 18 workers' houses and two civil servants' houses were available in a specially built housing complex from 1902 to 1905, later known as the Neuaubing Colony. From 1907, the Centralwerkstätte Aubing took over parts of the maintenance of passenger, baggage and mail coaches as well as railcars from the Munich works. From 1907 or 1908, Postal motor vehicles were also repaired in Aubing.

As a state-owned enterprise, the Royal Bavarian State Railways had planning sovereignty and could therefore build and expand the workshop without the approval of the municipality of Aubing. The plant was also exempt from municipal taxes. However, as the municipality had to provide the necessary infrastructure for the factory workers living in Aubing, this placed a heavy burden on the municipal budget.[6]

In 1907, construction work began on an additional switch workshop, and in 1910 Hall 11 was put into operation for switch production.[7] At this time, the workshop at the Aubing plant was the only turnout workshop of the Bavarian State Railways. From 1912, the Bavarian postal administration built its own repair workshop for postal vehicles on the site of the Centralwerkstätte, which was opened in 1914.

On November 13, 1913, the Bayerische Landtag approved the construction of a new hall for the repair of passenger cars and budgeted 2,887,000 marks for it. Due to the outbreak of the World War I, however, the preparatory work was abandoned in 1914 and the plans were not realized for the time being.[8][9] During the First World War, the Centralwerkstätte Aubing produced war materials; by 1918, 150,000 long grenades had been manufactured.[10] In 1915 the name was changed to Centralwerkstätte Neuaubing. In September 1918, the construction of a training workshop for locksmith apprentices began.[3][11]

Expansion measures of the German Reichsbahn and the Second World War

editFrom 1920, the Deutsche Reichsbahn referred to the Centralwerkstätte as the Hauptwerkstätte Neuaubing. In 1924, it was transferred to the Zentralmaschinenamt Munich of the Gruppenverwaltung Bayern and from then on operated under the name Reichsbahnausbesserungswerk Neuaubing (RAW Neuaubing). In the spring of 1921, the Deutsche Reichsbahn began construction of the passenger carriage hall, which had already been decided in 1913. However, strikes and workers' lockouts during the inflationary period delayed the completion of the hall. The shell of the building was completed in October 1924, and on 1 April 1927 the wagon repair shop, known as Hall 3, was finally fully opened. The expansion of the factory facilities required a higher heating capacity. As late as 1921, three of the five double-flame tube boilers were demolished and four new water tube boilers from Babcock & Wilcox were put into operation by 1922. The installation of an electric monorail for feeding coal, a traveling grate and a flue gas preheater significantly increased the amount of steam produced.

With the commissioning of the passenger coach hall, RAW Neuaubing took over the entire maintenance of passenger, baggage and mail coaches from RAW München, the former Centralwerkstätte München, on April 19, 1927. Freight car repairs, on the other hand, were initially handed over completely to RAW München and transferred to the new RAW München-Freimann by 1931.[8]

As part of the National Socialist reconstruction plans for the Munich railroad facilities, the repair works were to be expanded. The first preparatory construction work took place in 1938, but after the beginning of the World War II, work was stopped again. After the start of the war, the plant resumed repairing freight wagons in 1939. From then on, RAW Neuaubing was also responsible for the construction and repair of special vehicles for the Wehrmacht and the Deutsche Reichsbahn as part of special war services.[10][3] From 1940 to 1941, the Deutsche Reichsbahn built a new training workshop. In 1942 the plant was renamed Reichsbahnausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing following the incorporation of Aubing into the city of Munich.

In 1942, RAW Neuaubing developed a new method of work organization that was intended to rationalize the entire production process. The aim was to save 90,000 production hours within six months. After testing it in Neuaubing, the Deutsche Reichsbahn introduced the so-called Munich procedure uniformly in all German repair workshops.[12]

From 1943, the repair plant was increasingly the target of air raids by the United States Army Air Forces. After severe damage caused by air raids on July 19 and 21, 1944, the plant had to cease repairs completely for twelve days.[7][13] Switch production was soon resumed, but wagon production was restricted for some time due to the severe damage to halls 1 and 2. After a makeshift repair, the factory was able to resume full operations in September 1944.[14][11] During another air raid on April 19, 1945, the plant was hit by 20 explosive bombs, damaging two halls.[15] On April 30, 1945, the Munich-Neuaubing RAW was captured by American troops.[16]

Rationalization and modernization by the Deutsche Bundesbahn

editJust a few days after the surrender of the German troops, repair work was resumed in May 1945. Initially, however, only the most urgent damage could be repaired due to the poor supply of materials and spare parts. During this time, the RAW was a stronghold of communist protests in southern Germany. The works council member Karl Reisinger was persecuted during the Third Reich because of his illegal work for the Socialist Workers' Party and was convicted of preparation for high treason. After the war, he became a member and cadre of the KPD and led a strike in the RAW on November 7, 1947, over food rations. The cuts in rations were then suspended for railroad workers. Further communist-organized strikes took place in January and February 1948 at RAW Neuaubing. Reisinger was dismissed without notice in 1952.[17]

In 1948, the name was changed to Eisenbahnausbesserungswerk (EAW) München-Neuaubing and in 1951 to Ausbesserungswerk (AW) München-Neuaubing. In 1950, the Deutsche Bundesbahn (DB) was able to complete the reconstruction of the damaged workshops and fully resume passenger coach repairs. At this time, the plant consisted of 34 individual Meistereien, which were housed in 34 halls and buildings.[18]

As part of rationalization measures, the Deutsche Bundesbahn considered closing the plant in the 1960s. The plant was centralized and the various sub-workshops were gradually closed. In 1967, the railroad moved the points workshop to the Ausbesserungswerk Witten, and in 1969 it gave up the train lighting workshop and the workshop for brake valves. On November 13, 1969, the Central Office for Workshop Services of the Deutsche Bundesbahn decided to retain the Munich-Neuaubing workshop, which averted its closure. At the same time, however, DB decided on further rationalization measures and a reduction in the size of the plant. By the mid-1970s, all remaining sub-workshops, including the workshop for the surface treatment of small parts, were closed. Only the new sign workshop set up in the post-war period remained.[16] The area was reduced from 300,000 to around 250,000 square meters, so that the two switch construction workshops that were no longer in use were now located outside the factory premises. Many buildings that were no longer needed were demolished. From then on, the number of employees was to be limited to 1000. Apart from the sign workshop, in which train running signs, station signs and roller conveyor displays were produced, the tasks of the AW Neuaubing were now limited to the repair of passenger coaches.

On May 16, 1972, there was a major fire in the eastern wagon repair workshop when the outer skin of a conversion car of the type 3yg standing there for repair caught fire. caught fire. The fire spread quickly due to the hall's roof construction of wooden beams, asphalt cardboard and tar and could only be extinguished after two and a half hours. The fire destroyed 4000 square meters of the hall roof and the hall's steel shot blasting system.[7] Two employees at the plant suffered smoke inhalation. Five passenger coaches burnt out, 19 other coaches were removed from the danger zone in time by the employees. Property damage amounted to 6.5 million DM, the repair of the fire damage cost a further 1.8 million DM. The cause of the fire remains unknown.[19]

In 1972, construction work began on the relocation of the wheelset workshop in the southern wagon repair workshop. To this end, Deutsche Bundesbahn reduced the size of the bogie workshop by half and installed the equipment for the new wheelset workshop in the space freed up. DB installed a new wheelset lathe and conveyor system as well as an ultrasonic test bench and a wheel flange welding machine. A bogie washing machine and an axle box washing machine were also installed. DB completed work on the wheelset workshop in 1978. In 1980, a central electronics workshop for locomotive and carriage control was built in the southern repair workshop in an area previously used by the upholstery workshop.[20][3]

Until 1974, a separate factory passenger train ran for the employees between the München-Pasing station and the plant stop in the west of the site. A series ET 85 railcar was used for this purpose.[21][22]

Decommissioning and subsequent use of the site

editFrom 1994, Deutsche Bahn again carried out rationalization measures. From 1997, the maintenance depot became part of the DB Reise & Touristik division as a heavy maintenance depot C-Werk.[3] In June 2001, Deutsche Bahn decided to close the plant, which had 530 employees. On December 31, 2001, the Neuaubing repair workshop was shut down.[7] Only the central electronics plant, which belonged to DB Vehicle Maintenance from 2001, remained on the site. From 2002 to 2005, the Bayerisches Eisenbahnmuseum (BEM) used the factory facilities for the storage of historic rail vehicles.[23]

In 2003, the railway-owned real estate company Aurelis took over the site.[24] In 2008, nine buildings and the access gate to the former repair workshop were placed under a preservation order.[11] From 2013, an industrial estate was created on the southern part of the factory premises under the name Triebwerk. The listed halls were renovated from 2013 to 2015 and incorporated into the industrial estate. The north-eastern hall 1, which is not a listed building, was demolished and Deutsche Post AG built a new mechanized delivery base for DHL on its site by 2014.[25] In 2013 the former elevated bunkers of the plant on Papinstraße was demolished. In the south-western corner of the site, a new building for the DB Fahrzeuginstandhaltung electronics central plant (EZW) was constructed from October 2013 and completed in June 2015.[26][27]

In April 2015, Deutsche Bahn dismantled the points to the repair workshop as part of a track renewal on the Pasing-Herrsching line. As a result, the access tracks and the Gleisharfe north of the halls were dismantled.[28] Following the dismantling of the tracks, the new residential area Gleisharfe with around 500 apartments was built in the northern area of the plant from August 2016.[29][30]

Structure

editIn the north-east of the repair workshop is the access gate, through which two access tracks led into the repair workshop. Directly north of the access gate is a mechanical keeper's signal box, which still serves as a barrier post for the Brunhamstraße level crossing. Until the barriers were dismantled in 2015, it controlled the level crossing on Papinstraße, which was directly in front of the gate.[31]

In the west of the factory premises, between the northern switch construction workshop and the switch depot on Papinstraße, there was an operational stop for the employees of the repair workshop. The works platform was connected to the track network via the access track to the points depot. The access track and the track systems of the works stop were electrified.[32]

To the east of the two wagon repair workshops, twelve tracks led from the track yard to a transfer table, which extended over 200 meters almost across the entire width of the factory premises. The tracks of the Southern Wagon Repair Workshop in Hall 3 to the south were connected to the transfer table. It is designed as an eight-bay hall with an iron framework construction and covers an area of around 25,000 square meters.[33] Between the two northern wagon workshops and the transfer table were the woodworking workshop in the single-storey building 4 in the east, the locksmith's shop in the two-storey building 5 and the boiler house in the single-storey building 7. All three buildings are designed as gabled roof structures. To the south of the metalworking shop is the former administration building of the repair shop, which is referred to as Building 10. It is designed as a two-storey hipped roof building and has a clock tower as a ridge turret. To the west of the southern wagon repair workshop is the southern points workshop, designated as Hall 11, in a single-storey saddle roof building.[19]

There was another transfer table to the south of the southern switch construction workshop and Hall 3. The building of the former training workshop stands to the south of the transfer table. It consists of a three-storey main building with a hipped roof, to which long, single-storey extensions are attached to the west, south and east. Nine of the former factory buildings and the access gate have been listed buildings since 2008. In addition to the listed buildings, the former training workshop still exists; the other buildings were demolished by 2013.[34]

| Construction | Designation | Erection | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Eastern car repair shop | 1902–1906 | Canceled in 2013 |

| 2 | Western car repair shop | 1902–1906 | Monument |

| 3 | Southern car repair shop | 1921–1927 | Monument |

| 4 | Woodworking workshop | 1902–1906 | Monument |

| 5 | Turning shop and metalworking shop | 1902–1906 | Monument |

| 6 | Forge | 1902–1906 | canceled |

| 7 | Boiler house | 1902–1906 | Monument |

| 10 | Administration building II | 1902–1906 | Monument, formerly with spare parts store |

| 11 | Southern switch construction workshop | 1907–1910 | Monument |

| 12 | Northern switch construction workshop | 1912–1914 | Monument, with administration building I until 1926 repair workshop for postal vehicles |

| 21 | Canteen building | 1930 | with attached common room, demolished |

| 40 | Training workshop | 1940–1941 |

Tasks

editCar repair

editBy 1913, the plant's maintenance stock already comprised around 7,700 wagons, of which 2,000 were passenger carriages and 5,700 were freight wagons. During the First World War, the number of wagons to be repaired continued to rise; in 1919, 11,408 wagons were repaired. On April 19, 1927, the Neuaubing works handed over the complete repair of freight wagons to the RAW Munich; the last time around 9500 freight wagons were repaired in Neuaubing was in 1926. Instead, the Neuaubing RAW took over the maintenance of passenger, baggage and mail wagons completely, so that the number of repaired passenger wagons rose to a maximum of 10,500 by 1929.[8] In the following period, the repair output fell again to 6400 passenger coaches by 1932.[35]

In 1950, the Neuaubing maintenance depot maintained 82 driving trailer and sidecar, 3812 other passenger coaches, of which 2789 steering axle coaches and 1023 bogie coaches, as well as 456 railroad service coaches. By 1956, the maintenance stock had risen again to 5800 passenger carriages.[18] From 1965, TEE coaches were maintained in Neuaubing. In 1980 there were a total of 3069 wagons in the Neuaubing maintenance stock, including 207 TEE/IC wagons, 988 m wagons, 161 yl wagons, 1135 n wagons, 375 conversion wagons and 203 Luggage trolley.[36]

In 1990, the maintenance stock of the Neuaubing works still comprised 2493 wagons, including 531 IC wagons, 191 converted Interregio wagons and ten Messwagen of the Versuchsanstalt München.[19] With the transfer of the plant to DB Reise & Touristik, only long-distance coaches were repaired in Neuaubing from 1997.[3] With the closure of the works, Deutsche Bahn handed over the wagon repair work completely to the Neumünster and Wittenberge as of December 31, 2001.

Railcar and locomotive maintenance

editFrom 1930, the works repaired locomotives for the first time with the electric shunting locomotives E 80 01-05. RAW Neuaubing was responsible for maintaining the batteries and rectifiers, while the mechanical part was repaired by RAW München-Freimann.[37]

In 1950, the maintenance fleet of AW München-Neuaubing comprised 90 electric railcars and 13 accumulator railcars. In 1951, the repair of the accumulator railcars was handed over to the Ausbesserungswerk Limburg (Lahn).[16] In 1959 the AW Neuaubing handed over the repair of electric railcars completely to the AW Stuttgart-Bad Cannstatt, which put an end to railcar maintenance in Neuaubing.[3][38][39]

Conversion programs and special tasks

editIn addition, Straßenbahn München vehicles were repaired at the Neuaubing plant after war damage. From 1943 to 1945, the repair plant converted heavily damaged Baureihe E tramcars into new G-Wagen by placing new superstructures on the frames and bogies.[10] A total of 19 G series tramcars were produced.[40][37]

From October 1953 to December 1956, three-axle Umbau-Wagen of the Gattung 3yg were produced from older state railway wagons, followed by the production of four-axle conversion wagons of the Gattung 4yg from December 1956 to 1961.[41]

In 1987, the Interregio-Sitzwagenprogramm, another major conversion programme began at the Neuaubing maintenance depot, in the course of which DB converted and modernized older m-cars for Interregio use. From 1989, the conversion was carried out in cooperation with the Weiden repair works of Partner für Fahrzeugausstattung (PfA). In 1990, the Deutsche Bundesbahn transferred production completely to Weiden and from then on the Neuaubing workshop was only responsible for the acceptance of the converted coaches. By 1990, around 250 coaches had been converted in Neuaubing.[10]

Switch production

editIn 1910, switch production began in Hall 11 of the factory. The factory was the only turnout workshop of the Royal Bavarian State Railways. As switch production increased in the 1920s, the space in the previous hall was no longer sufficient. On November 1, 1928, the Deutsche Reichsbahn relocated the production of the individual switch components to hall 12, while the assembly of the switches remained in the previous hall 11. The switches were transported from the Neuaubing switch workshop to the main superstructure warehouses in Pasing and Nuremberg for acceptance. From 1937, the Deutsche Reichsbahn stored the manufactured turnouts directly in the new Neuaubing turnout warehouse.[42]

By expanding the turnout workshop, the Deutsche Reichsbahn was able to increase production from two to three turnout units per week in 1936 to six to eight turnout units per week in 1937. The target of 20 to 22 turnout units per week was almost reached by 1938. In 1938, the plant refurbished a total of 907 turnout units, built 51 new turnouts and handled turnout parts with a total weight of 2214 tons. Alongside Witten and Brandenburg-West, RAW Neuaubing was one of three Deutsche Reichsbahn plants for the construction of new turnouts. In 1967, the Deutsche Bundesbahn handed over switch production in Neuaubing completely to the Witten repair plant and dissolved the switch workshop.[12]

Employees and social institutions

editBy 1913, there were already 539 employees at the Centralwerkstätte. Due to the shortage of personnel during the First World War, the Bavarian State Railways deployed large numbers of prisoners of war as forced labor in the factory.[43][44] After the end of the war, the Demobilization Ordinance provided for the admission of external workers from the demobilized Bavarian army in addition to the former workers. As a result, the number of employees rose to 1535 in 1919 and there was a significant surplus of staff. As a result, the Centralwerkstätte abolished overtime and Sunday work and introduced a multi-shift operation. As a result, the work output per person was only about half as high as before the war. On August 1, 1919, the Centralwerkstätte therefore abolished double shifts again and reduced the number of employees back to 1100.

In 1921, the Turn- und Sportverein Neuaubing was founded for the employees of the plant. In 1930, the club bought a plot of land west of the repair works from Rudolf von Maffei, the owner of Gut Freiham, and built a sports facility there until 1936. After several name changes, the sports club became Railwaymen's Sports Club Sportfreunde Neuaubing in 1951 (ESV Neuaubing) emerged.[45]

On November 1, 1924, Albert Gollwitzer, the previous director of the Nuremberg maintenance depot, took over the management of the Neuaubing maintenance depot. On April 1, 1930, he moved to the RAW Munich-Freimann and became president of the Reichsbahndirektion München in 1933.[46]

From 1929 until his death on the German Nanga Parbat Expedition 1934, the mountaineer Willy Merkl was employed as an engineer in the turnout workshop in Neuaubing.[47]

As the number of workers increased, the Eisenbahner-Baugenossenschaft expanded its housing estate by 1929, so that there were eventually 163 apartments in the area between Limesstraße, Wiesentfelser Straße and Plankenfelser Straße. The land required for this was provided by the Deutsche Reichsbahn as part of the heritable building right. In 1941 the Aubing building cooperative was incorporated into the Eisenbahner-Baugenossenschaft München Hauptbahnhof (ebm).[48]

In 1930, 1408 workers were employed at the plant again. The decline in repair work caused the Deutsche Reichsbahn to lay off workers again and reduced the number of workers to 1159 by 1932. On May 1, 1933, the company founded its own works band, which initially consisted of 25 people and was later expanded to 44 members. It took part in various music competitions, marches and propaganda events in Munich.[49]

In the course of the economic upturn, the number of employees at the repair plant increased again from 1933. In the 1930s, a new Reichskleinsiedlung was built with detached houses for the workers. In 1930 the Deutsche Reichsbahn built a new canteen building, which it extended in 1936 with a community room attached to the south. In 1938 the canteen was given its own slaughterhouse with stables on the factory premises. In 1941 the Deutsche Reichsbahn opened a kindergarten in the south-east corner of the factory premises with a nurses' home known as the Barbaraheim.[50] During the Second World War, up to 2,480 people were employed at the plant in 1942 for special war work, including around 600 women and over 800 prisoners of war and forced laborers.[16] The forced labor camp Neuaubing was built north of the Pasing-Herrsching railroad line at the end of 1942 for the forced laborers working at the repair plant.[51]

In the post-war period, the number of employees fluctuated around 2000. In the 1950s, the number of employees rose from 1943 in 1950 to 2463 in 1956.[19] In 1975, Deutsche Bundesbahn opened a new works canteen equipped with a canteen kitchen. In the course of the rationalization measures in the 1970s, DB planned to limit the number of employees to 1,000, which was significantly undercut in 1980 with 885 employees.[52] In 1981 911 people were employed at the repair plant, including 103 civil servants, eleven salaried employees and 797 workshop workers.[53][3] In the following years, the number of employees remained largely constant; in 1990, 912 people were employed at AW München-Neuaubing.[8] As a result of Deutsche Bahn's rationalization measures, the number of employees fell again. In 2001, the last year of operation, 530 employees were still working in Neuaubing.[11]

Switch bearing

editIn 1937, the Deutsche Reichsbahn acquired another plot of land from Rudolf von Maffei to the west of the repair works and built a large switch depot there by 1938. Some areas and three buildings of the repair works were transferred to the switch depot. The 13 hectare storage area was used to store the turnout construction materials for the turnout workshop of the repair works as well as the completed turnouts. In contrast to the switch workshop, the Deutsche Reichsbahn ran the switch warehouse as an independent department that was not subordinate to the Neuaubing RAW. The switch depot was also responsible for all switch construction work at the Bavarian permanent way depots in Nuremberg, Pasing, Augsburg and Regensburg. The connecting track to the switch depot branched off from the access tracks directly in front of the access gate to the maintenance depot and ran along the north-western wall of the Neuaubing maintenance depot to the depot site.[42]

After the switch workshop was abandoned, the switch depot was used as a track depot from 1967. In 1971, the Deutsche Bundesbahn dissolved it as an independent department and placed it under the Augsburg-Oberhausen track construction yard as a branch office. Until its closure in 1980, the depot was mainly used for the assembly and dismantling of track yokes. Subsequently, most of the track systems on the site were dismantled and the buildings demolished. The site of the switch depot has lain fallow since then and has developed into an urban biotope due to its great diversity of flora and fauna.[11] In 2015 the access track to the track storage area, which had largely been in place until then, was completely dismantled.[28]

External links

edit- Frank Zimmermann: Munich-Neuaubing repair plant. History and pictures of the current state. In: spurensuche-eisenbahn.de, June 14, 2015.

- Munich-Neuaubing repair plant: Timeline. In: bahnstatistik.de.

Literature

edit- Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing 1906–1981, Freiburg: Eisenbahn-Kurier-Verlag, ISBN 3-88255-800-8

- Klaus-Dieter Korhammer, Armin Franzke, Ernst Rudolph (1991), Peter Lisson (ed.), Drehscheibe des Südens. Eisenbahnknoten München, Darmstadt: Hestra-Verlag, pp. 102–105, ISBN 3-7771-0236-9

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - Landeshauptstadt München, Kulturreferat (Ed): KulturGeschichtsPfad Stadtbezirk 22: Aubing-Lochhausen-Langwied. 2. Ed. 2015, p. 49–52.

- Robert Bopp (2003), 100 Jahre Bahnstrecke Pasing – Herrsching. Von der Königlich Bayerischen Lokalbahn zur S-Bahn-Linie 5, Germering, pp. 73–74, ISBN 3-00-011372-X

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)

References

edit- ^ a b "Schluß an der Isar. Das Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing vor dem Aus", Lok Magazin, vol. 7, Franckh-Kosmos, p. 51, 2001

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, pp. 12–13

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuabing: Zeittafel. In: bahnstatistik.de, retrieved 4 March 2017.

- ^ Korhammer, Franzke, Rudolph (1991), Drehscheibe des Südens, p. 155

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Korhammer, Franzke, Rudolph (1991), Drehscheibe des Südens, p. 157

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Landeshauptstadt München (ed.): KulturGeschichtsPfad Stadtbezirk 22. 2015, p. 14–15

- ^ a b c d Frank Zimmermann: Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing. In: spurensuche-eisenbahn.de, 14 June 2015, retrieved 21 January 2018.

- ^ a b c d Korhammer, Franzke, Rudolph (1991), Drehscheibe des Südens, p. 102

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, pp. 8–10

- ^ a b c d Korhammer, Franzke, Rudolph (1991), Drehscheibe des Südens, p. 105

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c d e Landeshauptstadt München (Hrsg.): KulturGeschichtsPfad Stadtbezirk 22. 2015, p. 49–52.

- ^ a b AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, p. 28

- ^ Bopp (2003), 100 Jahre Bahnstrecke Pasing – Herrsching, p. 74

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, pp. 10–14

- ^ Bopp (2003), 100 Jahre Bahnstrecke Pasing – Herrsching, p. 115

- ^ a b c d Korhammer, Franzke, Rudolph (1991), Drehscheibe des Südens, p. 103

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Günter Gerstenberg: Armut, Mangelwirtschaft – Im Winter 1946/47 ... In: Protest in München seit 1945, auf sub-bavaria.de, retrieved 26 May 2017.

- ^ a b AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, p. 35

- ^ a b c d Korhammer, Franzke, Rudolph (1991), Drehscheibe des Südens, p. 104

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, pp. 36–39

- ^ Peter Schricker (2005), Münchner Schienennahverkehr. Tram, S-Bahn, U-Bahn, O-Bus, München: GeraMond, p. 75, ISBN 3-7654-7137-2

- ^ Bopp (2003), 100 Jahre Bahnstrecke Pasing – Herrsching, p. 56

- ^ Vor 25 Jahren – Tag der offenen Tür im AW München-Neuaubing (Archived March 4, 2017 in the Internet Archive). In: mysnip.de, May 2, 2015.

- ^ Andreas Remien: Abgefahren. In: Süddeutsche Zeitung, 16 March 2017, retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ DHL baut Paketzustellbasis auf dem ehemaligen Eisenbahnausbesserungswerk – Bescherung aus dem „Triebwerk" (Archived December 4, 2016 in the Internet Archive). In: Hallo München, 24 April 2013.

- ^ Projekt in Aubing – Grundsteinlegung für Elektronikzentralwerkstatt. In: Abendzeitung, 7 October 2013, retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Peter T. Schmidt: Bahn eröffnet neues Werk – Die Zug-Doktoren von Neuaubing. In: Münchner Merkur, 29 June 2015, retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ a b Stefan von Lossow: KBS 999.8 – Die S 8 West: Pasing-Herrsching (Archived August 22, 2018, in the Internet Archive). In: mittenwaldbahn.de.

- ^ Neubauprojekt Gleisharfe in Neuaubing startet. In: hf-baugmbh.de, 29 August 2016, retrieved 2 December 2016.

- ^ Frank Pfeiffer: Schrankenposten von Itzelberg bis Reetz. In: entlang-der-gleise.de, September 25, 2019, retrieved on October 3, 2019.

- ^ Frank Pfeiffer: Schrankenposten von Itzelberg bis Reetz. In: entlang-der-gleise.de, 25 September 2019, retrieved 3 October 2019.

- ^ Werkszug AW Neuaubing (Archived January 9, 2017 in the Internet Archive). In: mysnip.de, 20 February 2014.

- ^ Nicole König: Neues Leben in riesigen Hallen – Große Pläne für ehemaliges Ausbesserungswerk der Bahn an der Papinstraße (Archived December 23, 2016, in the Internet Archive). In: Hallo München, 27 January 2010.

- ^ Denkmalliste für München (PDF) at the Bavarian State Office for Monument Preservation, retrieved on October 10, 2016.

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, pp. 14–17

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, p. 41

- ^ a b AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, p. 25

- ^ Korhammer, Franzke, Rudolph (1991), Drehscheibe des Südens, p. 160

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, pp. 21–22

- ^ Richard Feichtenschlager: G-Triebwagen und g-Beiwagen. In: strassenbahn-muenchen.de, 15 February 2009, retrieved 4 December 2016.

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, p. 36

- ^ a b AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, p. 26

- ^ Herbert Liedl (2006), Grundschule an der Limesstraße (ed.), "Die Anfänge von Neuaubing 1906–1942", Festschriftkalender Grundschule an der Limesstraße. 100 Jahre Schule (1906–2006). 30 Jahre Tagesheim (1976–2006), München

- ^ Herbert Liedl: „Gott segne die christliche Arbeit". 100 Jahre Katholischer Arbeiterverein Aubing. In: Pfarrbrief der Gemeinde St. Quirin. July 2009, p. 13–17

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, p. 32

- ^ Joachim Lilla: Gollwitzer, Albert. In: Bayerische Landesbibliothek Online, 25 November 2015, retrieved 10 September 2017.

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, pp. 105–107

- ^ Landeshauptstadt München (Ed.): KulturGeschichtsPfad Stadtbezirk 22. 2015, p. 61–62

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, p. 34

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, pp. 28–29

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, pp. 14–19

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, pp. 35–38

- ^ AW München-Neuaubing, ed. (1981), 75 Jahre Bundesbahn-Ausbesserungswerk München-Neuaubing, p. 40