This article needs additional citations for verification. (August 2023) |

Munster Irish (endonym: Gaelainn na Mumhan, Standard Irish: Gaeilge na Mumhan) is the dialect of the Irish language spoken in the province of Munster. Gaeltacht regions in Munster are found in the Gaeltachtaí of the Dingle Peninsula in west County Kerry, in the Iveragh Peninsula in south Kerry, in Cape Clear Island off the coast of west County Cork, in Muskerry West; Cúil Aodha, Ballingeary, Ballyvourney, Kilnamartyra, and Renaree of central County Cork; and in an Rinn and an Sean Phobal in Gaeltacht na nDéise in west County Waterford.

| Munster Irish | |

|---|---|

| Munster Gaelic | |

| Gaelainn na Mumhan | |

| Pronunciation | [ˈɡeːlˠən̠ʲ n̪ˠə ˈmˠuːnˠ] |

| Ethnicity | Irish |

Native speakers | 10,000[citation needed] (2012) |

Early forms | |

| Dialects | |

| Latin (Irish alphabet) Irish Braille | |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | muns1250 |

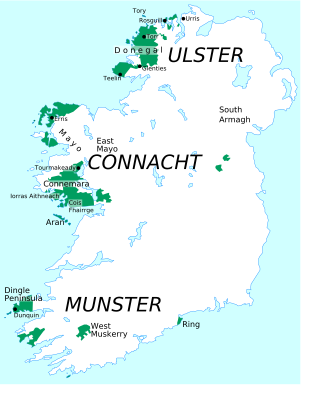

The three dialects of Irish, with Munster in the south. | |

History

editThe north and west of Dingle Peninsula (Irish: Corca Dhuibhne) are today the only place in Munster where Irish has survived as the daily spoken language of most of the community although the language is spoken on a daily basis by a minority in other official Gaeltachtaí in Munster.

Historically, the Irish language was spoken throughout Munster and Munster Irish had some influence on those parts of Connacht and Leinster bordering it such as Kilkenny, Wexford and south Galway and the Aran Islands.

Munster Irish played an important role in the Gaelic revival of the early 20th century. The noted author Peadar Ua Laoghaire wrote in Munster dialect and stated that he wrote his novel Séadna to show younger people what he viewed as good Irish:

Ag machtnamh dom air sin do thuigeas am' aigne ná raibh aon rud i n-aon chor againn, i bhfuirm leabhair, le cur i láimh aon leinbh chun na Gaeluinne do mhúineadh dhó. As mo mhachtnamh do shocaruigheas ar leabhar fé leith do sgrí' d'ár n-aos óg, leabhar go mbéadh caint ann a bhéadh glan ós na lochtaibh a bhí i bhformhór cainte na bhfilí; leabhar go mbéadh an chaint ann oireamhnach do'n aos óg, leabhar go mbéadh caint ann a thaithnfadh leis an aos óg. Siné an machtnamh a chuir fhéachaint orm "Séadna" do sgrí'. Do thaithn an leabhar le gach aoinne, óg agus aosta. Do léigheadh é dos na seandaoine agus do thaithn sé leó. D'airigheadar, rud nár airigheadar riamh go dtí san, a gcaint féin ag teacht amach a' leabhar chúcha. Do thaithn sé leis na daoinibh óga mar bhí cosmhalacht mhór idir Ghaeluinn an leabhair sin agus an Béarla a bhí 'n-a mbéalaibh féin.[1]

Peig Sayers was illiterate, but her autobiography, Peig, is also in Munster dialect and rapidly became a key text. Other influential Munster works are the autobiographies Fiche Blian ag Fás by Muiris Ó Súilleabháin and An tOileánach by Tomás Ó Criomhthain.

Lexicon

editMunster Irish differs from Ulster and Connacht Irish in a number of respects. Some words and phrases used in Munster Irish are not used in the other varieties, such as:

- in aon chor (Clear Island, Corca Dhuibhne, West Muskerry, Waterford) or ar aon chor (Clear Island, West Carbery, Waterford) "at any rate" (other dialects ar chor ar bith (Connacht) and ar scor ar bith (Ulster)

- fé, fí "under" (standard faoi)

- Gaelainn "Irish language" (Cork and Kerry), Gaeilinn (Waterford) (standard Gaeilge)

- ná "that...not" and nách "that is not" as the copular form (both nach in the standard)

- leis "also" (Connacht freisin, Ulster fosta)

- anso or atso "here" and ansan or atsan "there" instead of standard anseo and ansin, respectively

- In both demonstrative pronouns and adjectives speakers of Munster Irish differentiate between seo "this" and sin "that" following a palatalised consonant or front vowel and so "this" and san "that" following a velarised consonant or back vowel in final position: an bóthar so "this road", an bhó san "that cow", an chairt sin "that cart", an claí seo "this fence"

- the use of thá instead of tá in the extreme west of Corca Dhuibhne and in Gaeltacht na nDéise.

- the preposition chuig "to, towards", common in Connacht Irish and Ulster Irish where it developed as a back formation from the 3rd person singular preposition chuige "towards him" is not used in Munster. The form chun (from Classical Irish do chum), also found in the West and North, is used in preference.

- Munster Irish uses a fuller range of "looking" verbs, while these in Connacht and Ulster are restricted: féachaint "looking", "watching", breithniú "carefully observing", amharc "look, watch", glinniúint "gazing, staring", sealladh "looking" etc.

- the historic dative form tigh "house", as in Scots and Manx Gaelic, is now used as the nominative form (Standard teach)

- Munster retains the historic form of the personal pronoun sinn "us" which has largely been replaced with muid (or muinn in parts of Ulster) in most situations in Connacht and Ulster.

- Corca Dhuibhne and Gaeltacht na nDéise use the independent form cím (earlier do-chím, ad-chím, classical also do-chiú, ad-chiú) "I see" as well as the dependent form ficim / feicim (classical -faicim), while Muskerry and Clear Island use the forms chím (independent) and ficim.

- The adverbial forms chuige, a chuige in Corca Dhuibhne and a chuigint "at all" in Gaeltacht na nDéise are sometimes used in addition to in aon chor or ar aon chor

- The adjective cuibheasach /kiːsəx/ is used adverbially in phrases such as cuibheasach beag "rather small", "fairly small", cuibheasach mór "quite large". Connacht uses sách and Ulster íontach

- Faic, pioc, puinn and tada in West Munster, dada in Gaeltacht na nDéise, ní dúrt pioc "I said nothing at all", níl faic dá bharr agam "I have gained nothing by it"

- The interjections ambaiste, ambaist, ambasa, ambaic "Indeed!", "My word!", "My God!" in West Munster and amaite, amaite fhéinig in Gaeltacht na nDéise (ambaiste = dom bhaisteadh "by my baptism", am basa = dom basaibh "by my palms", ambaic = dom baic "by my heeding"; amaite = dom aite "my oddness")

- obann "sudden" instead of tobann in the other major dialects

- práta "potato", fata in Connacht and préata in Ulster

- oiriúnach "suitable", feiliúnach in Connacht and fóirsteanach in Ulster

- nóimint, nóimit, nóimeat, neomint, neomat, nóiméad in Connacht and bomaite in Donegal

- Munster differentiates between ach go háirithe "anyway", "anyhow" and go háirithe "particularly", "especially"

- gallúnach "soap", gallaoireach in Connacht and sópa in Ulster

- deifir is "difference" in Munster, and is a Latin loan: níl aon deifir eatarthu "there is no difference between them"; the Gaelic word deifir "hurry" is retained in the other dialects (c.f. Scottish Gaelic diofar "difference")

- deabhadh or deithneas "hurry" whereas the other major dialects use deifir

Phonology

editThe phonemic inventory of Munster Irish (based on the accent of West Muskerry in western Cork) is as shown in the following chart (based on Ó Cuív 1944; see International Phonetic Alphabet for an explanation of the symbols). Symbols appearing in the upper half of each row are velarized (traditionally called "broad" consonants) while those in the bottom half are palatalized ("slender"). The consonant /h/ is neither broad or slender.

| Consonant phonemes |

Bilabial | Coronal | Dorsal | Glottal | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dental | Alveolar | Palatoalveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||||||||||

| Stops | pˠ pʲ |

bˠ bʲ |

t̪ˠ |

d̪ˠ |

tʲ |

dʲ |

c |

ɟ |

k |

ɡ |

||||

| Fricative/ Approximant |

ɸˠ ɸʲ |

βˠ βʲ |

sˠ |

ʃ |

ç |

j |

x |

ɣ |

h | |||||

| Nasal | mˠ mʲ |

n̪ˠ |

nʲ |

ɲ |

ŋ |

|||||||||

| Tap | ɾˠ ɾʲ |

|||||||||||||

| Lateral approximant |

l̪ˠ |

lʲ |

||||||||||||

The vowels of Munster Irish are as shown on the following chart. These positions are only approximate, as vowels are strongly influenced by the palatalization and velarization of surrounding consonants.

In addition, Munster has the diphthongs /iə, ia, uə, əi, ai, au, ou/.

Some characteristics of Munster that distinguish it from the other dialects are:

- The fricative [βˠ] is found in syllable-onset position. (Connacht and Ulster have [w] here.) For example, bhog "moved" is pronounced [βˠɔɡ] as opposed to [wɔɡ] elsewhere.

- The diphthongs /əi/, /ou/, and /ia/ occur in Munster, but not in the other dialects.

- Word-internal clusters of obstruent + sonorant, [m] + [n/r], and stop + fricative are broken up by an epenthetic [ə], except that plosive + liquid remains in the onset of a stressed syllable. For example, eaglais "church" is pronounced [ˈɑɡəl̪ˠɪʃ], but Aibreán "April" is [aˈbrɑːn̪ˠ] (as if spelled Abrán).

- Orthographic short a is diphthongized (rather than lengthened) before word-final m and the Old Irish tense sonorants spelled nn, ll (e.g. ceann [kʲaun̪ˠ] "head").

- Word-final /j/ is realized as [ɟ], e.g. marcaigh "horsemen" [ˈmˠɑɾˠkəɟ].

- Stress is attracted to noninitial heavy syllables: corcán [kəɾˠˈkɑːn̪ˠ] "pot", mealbhóg [mʲal̪ˠəˈβˠoːɡ] "satchel". Stress is also attracted to [ax, ɑx] in the second syllable when the vowel in the initial syllable is short: coileach [kəˈlʲax] "rooster", beannacht [bʲəˈn̪ˠɑxt̪ˠ] "blessing", bacacha [bˠəˈkɑxə] "lame" (pl.).

- In some varieties, long /ɑː/ is rounded to [ɒː]. [citation needed]

Morphology

editIrish verbs are characterized by having a mixture of analytic forms (where information about person is provided by a pronoun) and synthetic forms (where information about number is provided in an ending on the verb) in their conjugation. Munster Irish has preserved nearly all of the synthetic forms, except for the second-person plural forms in the present and future:

| Munster | Standard | Gloss |

|---|---|---|

| Present | ||

| molaim | molaim | "I (sg.) praise" |

| molair | molann tú | "you (sg.) praise" |

| molann sé | molann sé | "he praises" |

| molaimíd, molam | molaimid | "we praise" |

| molann sibh (archaic: moltaoi) | molann sibh | "you (pl.) praise" |

| molaid (siad) | molann siad | "they praise" |

| Past | ||

| mholas | mhol mé | "I praised" |

| mholais | mhol tú | "you (sg.) praised" |

| mhol sé | mhol sé | "he praised" |

| mholamair | mholamar | "we praised" |

| mholabhair | mhol sibh | "you (pl.) praised" |

| mholadar | mhol siad | "they praised" |

| Future | ||

| molfad | molfaidh mé | "I will praise" |

| molfair | molfaidh tú | "you (sg.) will praise" |

| molfaidh sé | molfaidh sé | "he will praise" |

| molfaimíd | molfaimid | "we will praise" |

| molfaidh sibh | molfaidh sibh | "you (pl.) will praise" |

| molfaid (siad) | molfaidh siad | "they will praise" |

Some irregular verbs have different forms in Munster than in the standard (see Dependent and independent verb forms for the independent/dependent distinction):

| Munster independent | Munster dependent | Standard independent | Standard dependent | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| chím | ní fheicim | feicim | ní fheicim | "I see, I do not see" |

| (do) chonac | ní fheaca | chonaic mé | ní fhaca mé | "I saw, I did not see" |

| deinim | ní dheinim | déanaim | ní dhéanaim | "I do, I do not" |

| (do) dheineas | níor dheineas | rinne mé | ní dhearna mé | "I did, I did not" |

| (do) chuas | ní dheaghas/níor chuas | chuaigh mé | ní dheachaigh mé | "I went, I did not go" |

| gheibhim | ní bhfaighim | faighim | ní bhfaighim | "I get, I do not get" |

Past tense verbs can take the particle do in Munster Irish, even when they begin with consonants. In the standard language, the particle is used only before vowels. For example, Munster do bhris sé or bhris sé "he broke" (standard only bhris sé).

The initial mutations of Munster Irish are generally the same as in the standard language and the other dialects. Some Munster speakers, however, use /ɾʲ/ as the lenition equivalent of /ɾˠ/ in at least some cases, as in a rí /ə ɾʲiː/ "O king!" (Sjoestedt 1931:46), do rug /d̪ˠə ɾʲʊɡ/ "gave birth" (Ó Cuív 1944:122), ní raghaid /nʲiː ɾʲəidʲ/ "they will not go" (Breatnach 1947:143).

Syntax

editOne significant syntactic difference between Munster and other dialects is that in Munster (excepting Gaeltacht na nDéise), go ("that") is used instead of a as the indirect relative particle:

- an fear go bhfuil a dheirfiúr san ospidéal "the man whose sister is in the hospital" (standard an fear a bhfuil...)

Another difference is seen in the copula. Fear is ea mé is used in addition to Is fear mé.

Notable speakers

editThis section needs expansion. You can help by adding to it. (June 2022) |

Some notable Irish singers who sing songs in the Munster Irish dialect include Nioclás Tóibín, Elizabeth Cronin, Labhrás Ó Cadhla, Muireann Nic Amhlaoibh, Seán de hÓra, Diarmuid Ó Súilleabháin, Seosaimhín Ní Bheaglaoich and Máire Ní Chéilleachair.

Four of the most notable Irish writers as Gaeilge (in Irish) hail from the Munster Gaeltacht: Tomás Ó Criomhthain whose most well-known book is the autobiographical An tOileáineach (The Islandman). Peig and Machnamh Seanamhná (An Old Woman's Reflections) by Peig Sayers was a fixture on the secondary school Irish syllabus for several decades. The other two authors are Muiris Ó Súilleabháin with Fiche Bliain ag Fás (Twenty Years A-Growing) and Eilís Ní Shuilleabháin's Letters from the Great Blasket.

References

edit- ^ Ua Laoghaire 1915, p. 215.

Bibliography

edit- Breatnach, Risteard B. (1947). The Irish of Ring, Co. Waterford. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 0-901282-50-2.

- De Bhial, Tomás (1984). An Cabhsa (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: An Gúm.

- Dillon, Myles; Ó Cróinín, Donnacha (1961). Teach Yourself Irish. London: English Universities Press.

- Mac Clúin, Seóirse (1922). Réilthíní Óir (in Irish). Vol. 1. Comhlucht Oideachais na h-Éirean.

- —— (1922). Réilthíní Óir (in Irish). Vol. 2. Comhlucht Oideachais na h-Éirean.

- Nic Phaidin, Caoilfhionn (1987). de Bhaldraithe, Tomás (ed.). Cnuasach Focal Ó Uíbh Ráthach. Deascán Foclóireachta (in Irish). Vol. 6. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. ISBN 978-0-90-171457-2.

- Nikolaev, Dmitry; Kukhto, Anton (September 2016). An update on the phonology of Gaeilge Chorca Dhuibhne. Celtic Linguistics Conference. Cardiff University. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.11371.34088.

- Ó Buachalla, Breandán (2003). An Teanga Bheo: Gaeilge Chléire. Dublin: Institiúid Teangeolaíochta Éireann. ISBN 0-946452-98-9.

- —— (2017). Cnuasach Chléire. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 978-1-85-500234-0.

- Ó Cuív, Brian (1944). The Irish of West Muskerry, Co. Cork. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 0-901282-52-9.

- Ó hAirt, Diarmaid (1988). de Bhaldraithe, Tomás (ed.). Díolaim Dhéiseach. Deascán Foclóireachta (in Irish). Vol. 7. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. ISBN 978-0-90-171476-3.

- Ó hÓgáin, Éamonn (1984). Díolaim Focal (A) ó Chorca Dhuibhne. Deascán Foclóireachta. Vol. 3. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. ISBN 978-0-90-171430-5.

- Ó Sé, Diarmuid (1995). An Teanga Bheo: Corca Dhuibhne. Institúid Teangeolaíochta Éireann. ISBN 0-946452-82-2.

- Ó Sé, Diarmuid (2000). Gaeilge Chorca Dhuibhne. Tuarascáil Taighde (in Irish). Vol. 26. Dublin: Institiúid Teangeolaíochta Éireann. ISBN 0-946452-97-0.

- Sjoestedt, Marie-Louise (1931). Phonétique d'un parler irlandais de Kerry (in French). Paris: Librairie Ernest Leroux.

- Wagner, Heinrich (1966). Linguistic Atlas and Survey of Irish Dialects. Vol. II: The Dialects of Munster. Dublin: Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 0-901282-46-4.

- Ward, Alan (1974). The Grammatical Structure of Munster Irish (PhD). University of Dublin.

Literature

edit- Breatnach, Nioclás (1998). Ar Bóthar Dom. Rinn Ó gCuanach: Coláiste na Rinne. [folklore, Ring]

- de Mórdha, Mícheál, ed. (1998). Bláithín = Flower. Ceiliúradh an Bhlascaoid. Vol. 1. Dingle: An Sagart. [Kerry]

- de Róiste, Proinsias (2001). Ó hÓgáin, Dáithí (ed.). Binsín Luachra: gearrscéalta agus seanchas. Dublin: An Clóchomhar. [short stories, folklore, Limerick]

- Gunn, Marion, ed. (1990). Céad Fáilte go Cléire. Dublin: An Clóchomhar. [folklore, Cape Clear Island]

- Mac an tSíthigh, Domhnall (2000). An Baile i bhFad Siar. Dublin: Coiscéim. [Dingle Peninsula]

- Mac Síthigh, Domhnall (2004). Fan inti. Dublin: Coiscéim. [Dingle Peninsula]

- Ní Chéileachair, Síle; Ó Céileachair, Donncha (1955). Bullaí Mhártain. Dublin: Sáirséal agus Dill. [Coolea]

- Ní Chéilleachair, Máire, ed. (1998). Tomás Ó Criomhthain, 1855-1937. Ceiliúradh an Bhlascaoid. Vol. 2. Dingle: An Sagart. [Kerry]

- ——, ed. (1999). Peig Sayers, scéalaí, 1873-1958. Ceiliúradh an Bhlascaoid. Vol. 3. Dublin: Coiscéim. [Kerry]

- ——, ed. (2000). Seoirse Mac Tomáis : 1903-1987. Ceiliúradh an Bhlascaoid. Vol. 4. Dublin: Coiscéim. [Kerry]

- ——, ed. (2000). Muiris Ó Súilleabháin 1904-1950. Ceiliúradh an Bhlascaoid. Vol. 5. Dublin: Coiscéim. [Kerry]

- ——, ed. (2001). Oideachas agus Oiliúint ar an mBlascaod Mór. Ceiliúradh an Bhlascaoid. Vol. 6. Dublin: Coiscéim. [Kerry]

- ——, ed. (2004). Fómhar na Mara. Ceiliúradh an Bhlascaoid. Vol. 7. Dublin: Coiscéim. [Kerry]

- ——, ed. (2005). Tréigean an Oileáin. Ceiliúradh an Bhlascaoid. Vol. 8. Dublin: Coiscéim. [Kerry]

- Ní Fhaoláin, Áine Máire, ed. (1995). Scéalta agus Seanchas Phádraig Uí Ghrífín. Dán agus Tallann. Vol. 4. Dingle: An Sagart. [Kerry]

- Ní Ghuithín, Máire (1986). Bean an Oileáin. Dublin: Coiscéim. [Kerry/Blasket Islands]

- Ní Mhioncháin, Máiréad (1999). Verling, Máirtín (ed.). Béarrach Mná ag Caint. collected by Tadhg Ó Murchú. Inverin: Cló Iar-Chonnachta. ISBN 1-902420 05-5.

- Ní Shúilleabháin, Eibhlín (2000). Ní Longsigh, Máiréad (ed.). Cín Lae Eibhlín Ní Shúilleabháin. illustrated by Tomáisín Ó Cíobháin. Dublin: Coiscéim. [Kerry/Blasket Islands]

- Ó Caoimh, Séamas (1989). Ó Connchúir, Éamon (ed.). An Sléibhteánach. edited for print by Pádraig Ó Fiannachta. Maynooth: An Sagart. [Tipperary]

- Ó Cearnaigh, Seán Sheáin (1974). An tOileán a Tréigeadh. Dublin: Sáirséal agus Dill. [Kerry/Blasket Islands]

- Ó Cinnéide, Tomás (1996). Ar Seachrán. Maynooth: An Sagart.

- Ó Cíobháin, Ger (1992). Ó Dúshláine, Tadhg (ed.). An Giorria san Aer. Maynooth: An Sagart.

- Ó Cíobháin, Pádraig (1991). Le Gealaigh. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (1992). An Gealas i Lár na Léithe. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (1992). An Grá faoi Cheilt. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (1995). Desiderius a Dó. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (1998). Ar Gach Maoilinn Tá Síocháin. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (1999). Tá Solas ná hÉagann Choíche. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- Ó Criomhthain, Seán (1991). Lá Dár Saol. Dublin: An Gúm.

- ——; Ó Criomhthain, Tomás (1997). Ó Fiannachta, Pádraig (ed.). Cleití Gé ón mBlascaod Mór. Dingle: An Sagart.

- Ó Criomhthain, Tomás (1997). Allagar na hInise. Dublin: An Gúm.

- —— (1980). Ua Maoileoin, Pádraig (ed.). An tOileánach. Dublin: Helicon Teoranta/An Comhlacht Oideachais.

- —— (1997). Bloghanna ón mBlascaod. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- Ó Cróinín, Seán (1985). Ó Cróinín, Donncha (ed.). Seanachas ó Chairbre 1. Scríbhinní Béaloidis. Vol. 13. University College Dublin: Comhairle Bhéaloideas Éireann. ISBN 978-0-90-112090-8.

- Ó hEoghusa, Tomás (2001). Solas san Fhuinneog. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- Ó Laoghaire, Peadar. Eisirt. Dublin: Brún agus Ó Nualláin Teoranta.

- ——. An Cleasaí. Dublin: Longmans, Brún agus Ó Nualláin Teoranta.

- —— (1999). Mo Scéal Féin. Dublin: Cló Thalbóid.

- ——. Mac Mathúna, Liam (ed.). Séadna. foreword by Brian Ó Cuív. Dublin: Carbad.

- Ó Murchú, Pádraig (1996). Verling, Máirtín (ed.). Gort Broc: Scéalta agus Seanchas ó Bhéarra. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- Ó Sé, Maidhc Dainín (2017) [1987]. A Thig Ná Tit orm. Dublin: C.J. Fallon. ISBN 978-0-71-441212-2.

- —— (1988). Corcán na dTrí gCos. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (1993). Dochtúir na bPiast. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (2001). Lilí Frainc. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (1998). Madraí na nOcht gCos. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (1999). Mair, a Chapaill. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (2003). Mura mBuafam - Suathfam. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (1990). Tae le Tae. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (2005). Idir dhá lios agus Nuadha. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- Ó Síocháin, Conchúr (1977). Seanchas Chléire. collected by Ciarán Ó Síocháin and Mícheál Ó Síocháin. Dublin: Oifig an tSoláthair.

- Ó Siochfhradha, Pádraig (1913). Cath Fionntrágha (in Irish). Baile Átha Cliath: Connradh na Gaedhilge.

- —— (1926). Seanfhocail na Muimhneach. Corcaigh: Cló-chualacht Seandúna.

- Ó Súilleabháin, Muiris (1998). Fiche Bliain ag Fás. Dingle: An Sagart.

- —— (2000). Uí Aimhirgín, Nuala (ed.). Ó Oileán go Cuilleán. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- Ó Súilleabháin, Páid (1995). Ag Coimeád na Síochána. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- Sayers, Peig (1992). Machnamh Seanmhná. Dublin: An Gúm.

- —— (1936). Peig.

- Tyers, Pádraig (1982). Leoithne Aniar. Baile an Fhirtéaraigh: Cló Dhuibhne.

- —— (1992). Malairt Beatha. Dunquin: Inné Teoranta.

- —— (2000). An tAthair Tadhg. Dingle: An Sagart.

- —— (1999). Abair Leat Joe Daly. Dingle: An Sagart.

- —— (2003). Sliabh gCua m'Óige. Dingle: An Sagart.

- Ua Ciarmhaic, Mícheál (1996). Iníon Keevack. Dublin: An Gúm.

- —— (1989). Ríocht na dTonn. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (2000). Guth ón Sceilg. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- —— (1986). An Gabhar sa Teampall. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- Ua Laoghaire, Peadar (1915). Mo Sgéal Féin.

- Ua Maoileoin, Pádraig (1978). Ár Leithéidí Arís : Cnuasach de Shaothar Ilchineálach. Dublin: Clódhanna Teoranta.

- —— (1968). Bríde Bhán. Dublin: Sairséal agus Dill.

- —— (1969). De Réir Uimhreacha. Dublin: Muintir an Dúna.

- —— (1960). Na hAird ó Thuaidh. Dublin: Sáirséal agus Dill.

- —— (1983). Ó Thuaidh!. Dublin: Sáirséal Ó Marcaigh.

- —— (2001). An Stát versus Dugdale. Dublin: Coiscéim.

- Uí Fhoghlú, Áine (2019). Scéalta agus Seanchas: Potatoes, Children and Seaweed. Foilseacháin Scoil Scairte. ISBN 9781916178809.

- Verling, Máirtín, ed. (2007). Leabhar Mhaidhc Dháith : Scéalta agus Seanchas ón Rinn. Dingle: An Sagart. Gaeltacht na nDéise, Co. Waterford]