The musky rat-kangaroo (Hypsiprymnodon moschatus) is a small marsupial found only in the rainforests of northeastern Australia. First described in the later 19th century, the only other species are known from fossil specimens. They are similar in appearance to potoroos and bettongs, but are not as closely related. Their omnivorous diet is known to include materials such as fruit and fungi, as well as small animals such as insects and other invertebrates.

| Musky rat-kangaroo[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Atherton Tableland, Queensland | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Diprotodontia |

| Family: | Hypsiprymnodontidae |

| Genus: | Hypsiprymnodon |

| Species: | H. moschatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Hypsiprymnodon moschatus | |

| |

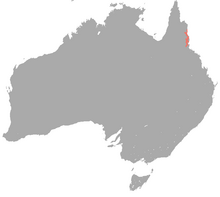

| Musky rat-kangaroo range | |

Taxonomy

editThe description of this species, assigned to a new genus Hypsiprymnodon, was published in 1876 by Edward Pierson Ramsay, a curator at the Australian Museum.[3] The syntypes are part of the museum's collection, mounted specimens of a male and female collected at Rockingham Bay, Queensland.[4] Ramsay's specimens were obtained during European settlement of northeastern Australia on an expedition toward the Herbert River.[5] A description of the species was provided by Richard Owen in the year after Ramsay's publication, the name Pleopus nudicaudatus, describing the five toes of the hind foot and its scaly, naked tail, is now regarded as a synonym.[6] Ramsay had provisionally assigned the species to the genus Hypsiprymnus, but in his review of the dentition he proposed to separate them to a new genus.[3] Hypsiprymnodon moschatus has been placed with the subfamily Hypsiprymnodontinae of the family Potoroidae, the most recent classification[1] places it in the family Hypsiprymnodontidae with prehistoric taxa.

The specific epithet is derived from Latin term moschatus, meaning musky.[7] The description as a new species of 'rat-kangaroo' was the last of the 19th century, bringing the total to nine species, and no other new species would be formally described for another 90 years.[5]

Description

editHypsiprymnodon moschatus is the smallest species of the macropod order, weighing around 500 grams (18 oz). The total length of the head and body is 155 to 270 millimetres (6.1 to 10.6 in), the weight range 360 to 680 grams (13 to 24 oz).[8] Sexual dimorphism is not readily apparent in this species, although the females may be slightly larger.[9] They have a long black tail, measuring from 125 to 160 mm (4.9 to 6.3 in). The appearance of the tail is scaly, rather than hairy, and proportionally shorter than the length of the head and body.[8] Their ears are also nearly hairless and appear leathery.[10] The pelage is a uniform, deep and rich brown colour with reddish highlights over most of the body, the head and lower parts are somewhat greyish.[8] The dark and chocolatey colour of the fur distinguish them from the other living 'rat-kangaroos'. A steel grey colour at the head grades into the rich brown of the body.[10] The feet of H. moschatus are blackish and, uniquely among the macropods, have five toes at the hind foot. A band of white, variously slight to distinct, appears from the belly toward the throat. The animal emits a noticeable musky odour.[8]

Dentition of the species resembles that of the extant potoroids, but for that family's incisor formula of I3/1. The dental formula of H. moschatus is I3/2 C1/0 PM1/1 M4/4. Two premolars found in juveniles are replaced at maturity when a single sectorial premolar erupts. The sequence of emerging molars and premolars allows the age of the individual to be determined. Hypsiprymnodon moschatus have a fine and delicate skull structure with a rostrum that is narrow and elongate. A long nasal bone structure and distance between the canine and premolar teeth is large.[11]

Distribution and habitat

editThe species only occurs in the northeastern part of the continent. They may be locally common in remaining areas of extensive rainforest and can occur at high and low elevations. The distribution range extends from west of Ingham, Queensland at Mt. Lee to Mt. Amos south of Cooktown. They are found in low altitude rainforests, such as Cape Tribulation and Mission Beach, and within the montane habitat of the Carbine, Atherton and Windsor tableland regions.[8] The population density of H. moschatus is from 1.40 to 4.50 animals per hectare.[12]

Behaviour

editA usually solitary animal that is only active during the day, distinguishing them from the nocturnal habits of the rat-kangaroos in the Potoroidae family. They are most active in the morning and afternoon, retiring to their shelter during the middle of the day.[13] They are mostly terrestrial, foraging at the forest floor, although they are able to move through the branches of the lower vegetation.

A nest is roughly constructed at a site where the animal shelters while sleeping.[8] Observations of the behaviour within its dense habitat presented difficulties to early field work, however, the use of a thread, lightly glued to the animal and fed from a spool, allowed the activity and range of males and females to be more accurately evaluated. The individual ranges overlap in both their foraging and nest site. Males may venture out in a range from 0.8 to 4.2 hectares, while females are recorded foraging over a smaller sized area of up to 2.2 ha. Although they are usually solitary in the activities, several may gather to feed at fallen fruit.

Their omnivorous diet comprises fruits and fungi along with some insects and other invertebrates, found among the leaf litter and lower storey of the rainforest.[8] The composition of the diet has been described as omnivorous, perhaps with reduced capacity for the carnivory of some fossil species of propleonines, but other records suggest the diet is largely frugivorous.[14]

Aggressive behaviours between males may be displayed during the austral spring and summer months, vigorously pursuing each other for around 30 seconds. The male's encounters, sometimes in competition for fruit, increase in frequency during breeding months; physical interactions between the males are restricted to striking with the front paw.[15] Reproductive activity is mostly from October to April, the usual litter size is two offspring. The newborns travel in the pouch of the mother for about 21 weeks, and then are left at the nest while the mother forages until the juveniles are fully weaned.[8] The earliest records note that the animal was elusive and discreet in its nature, and that specimens were difficult to obtain.[3]

Regular activity is conducted on all four limbs, but unlike the bettongs and potoroos, the musky rat-kangaroo bounds using all its paws when moving rapidly. This resembles the characteristic hopping of a rabbit more than that of its macropod relations.[10] It moves by extending its body and then bringing both of its hind legs forward, and uses an opposable toe on the hind foot to climb trees.[16]

Ecology

editA number of parasitic species are presumed to be associated with H. moschatus, including internal organisms such as roundworm and tapeworm species and ectoparasites such as ticks, mites, lice and fleas; the identified species of mites (Acari) are those of genera Mesolaelaps and Trichosurolaelaps.[17]

Musky rat-kangaroos have been protected from many of the threatening factors that greatly reduced the potoroine species, and their rainforest habitat has in part remain secluded and conserved. The species remains vulnerable to fragmentation of the population by land clearing, which disrupts the ability to recolonise and increases genetic isolation, Their role in seed dispersal within their range is likewise important to the ecology of their tropical rainforest habitat.[18] By carrying a fleshy fruit away to be consumed, or pressing them into earth as a cache, Hypsiprymnodon moschatus gives advantage to the plant's potential for recruitment. This interaction between plants and mammal has been compared to those on other continents, such as the squirrels and agoutis, and posited as an example of convergent evolution.[19]

The lack of size difference in the sexes corresponds to a limited home range for males, the inability to range beyond the female also allows greater attention to sexual competitors.[9] The high level of overlaps in range of a local populous allows high population densities.[20]

Systematics

editAfter the first description of the species, the musky rat-kangaroo was allied to various familial relationships. Later revisions have strongly indicated deep divergence from the extant potoroid marsupials, Bettongia and Potorous, and separated at the family level as Hypsiprymnodontidae. The discovery of fossil specimens has revealed a more widespread and diverse lineage in Miocene Australia. The placement may be summarised as,

- Family Hypsiprymnodontidae[21]

- Subfamily Hypsiprymnodontinae

- Genus Hypsiprymnodon [extant and fossil species]

- Hypsiprymnodon moschatus, musky rat-kangaroo

- Subfamily †Propleopinae [fossil species]

- Genus Hypsiprymnodon [extant and fossil species]

- Subfamily Hypsiprymnodontinae

References

edit- ^ Groves, C. P. (2005). "Order Diprotodontia". In Wilson, D. E.; Reeder, D. M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 43–70. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Burnett, S.; Winter, J.; Martin, R. (2016). "Hypsiprymnodon moschatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T40559A21963734. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T40559A21963734.en. Retrieved 12 November 2021.

- ^ a b c d Ramsay, E.P. (1875). "Description of a new genus and species of rat kangaroo, allied to the genus Hypsiprymnus, proposed to be called 'Hypsiprymnodon moschatus". Proceedings of the Linnean Society of New South Wales. 1: 33–35. doi:10.5962/bhl.part.12382.

- ^ "Species Hypsiprymnodon moschatus Ramsay, 1876". Australian Faunal Directory. Retrieved 20 March 2019.

- ^ a b Claridge 2007, p. 5–6.

- ^ Owen, R. (1877). "On a new marsupial from Australia". The Annals and Magazine of Natural History; Zoology, Botany, and Geology. 4. 20 (120): 542. doi:10.1080/00222937708682281.

- ^ Strahan, R.; Cayley, N. (1987). What mammal is that?. North Ryde: Cornstalk. pp. 118. ISBN 0207153256.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Menkhorst, P.W.; Knight, F. (2011). A field guide to the mammals of Australia (3rd ed.). Melbourne: Oxford University Press. p. 110. ISBN 9780195573954.

- ^ a b Claridge 2007, p. 99.

- ^ a b c Claridge 2007, p. 29.

- ^ Claridge 2007, pp. 30, 31.

- ^ Claridge 2007, p. 71.

- ^ Claridge 2007, p. 66.

- ^ Wroe, Stephen; Brammall, Jenni; et al. (1998). "The Skull of Ekaltadeta ima (Marsupialia, Hypsiprymnodontidae?): An Analysis of Some Marsupial Cranial Features and a Re-Investigation of Propleopine Phylogeny, with Notes on the Inference of Carnivory in Mammals". Journal of Paleontology. 72 (4): 738–751. Bibcode:1998JPal...72..738W. doi:10.1017/S0022336000040439. ISSN 0022-3360. JSTOR 1306699. S2CID 86359996.

- ^ Claridge 2007, pp. 81, 101.

- ^ McKay, G. (Ed.). (1999). Mammals (p. 60). San Francisco: Weldon Owen Inc. ISBN 1-875137-59-9

- ^ Claridge 2007, p. 35.

- ^ Claridge 2007, p. 161.

- ^ Dennis, A.J. (2003). "Scatter-hoarding by musky rat-kangaroos, Hypsiprymnodon moschatus, a tropical rain-forest marsupial from Australia: implications for seed dispersal". Journal of Tropical Ecology. 19 (6): 619–627. doi:10.1017/S0266467403006023. ISSN 1469-7831. S2CID 85090564.

- ^ Claridge 2007, p. 80.

- ^ Bates, H.; Travouillon, K.J.; et al. (2014). "Three new Miocene species of musky rat-kangaroos (Hypsiprymnodontidae, Macropodoidea): description, phylogenetics and paleoecology" (PDF). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 34 (2): 383–396. Bibcode:2014JVPal..34..383B. doi:10.1080/02724634.2013.812098. S2CID 86139768.

Sources

edit- Claridge, A.W.; Seebeck, J.H.; et al. (2007). Bettongs, potoroos, and the musky rat-kangaroo. Collingwood, Victoria: CSIRO Pub. ISBN 9780643093416.