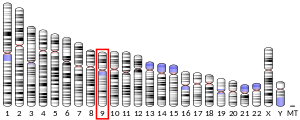

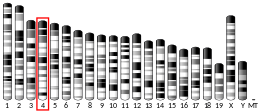

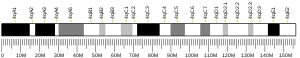

Nuclear factor 1 B-type is a protein that in humans is encoded by the NFIB gene.[5][6]

NFIB haploinsufficiency is also associated with intellectual disability and macrocephaly, as are NFIA and NFIX.[7]

Embryonic development

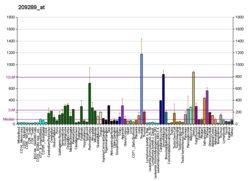

editThe NFIB gene is a part of the NFI gene complex that includes three other genes (NFIA, NFIC and NFIX).[8][9] The NFIB gene is a protein coding gene that also serves as a transcription factor.[10] This gene is essential in embryonic development and it works together with its gene complex to initiate tissue differentiation in the fetus. NFIB has the highest concentrations in the lung, skeletal muscle and heart but is also found in the areas of the developing liver, kidneys and brain.[8]

Through knockout experiments, researchers found that mice without the NFIB gene have severely underdeveloped lungs.[9][11] This mutation does not seem to cause spontaneous abortions because in utero the fetus does not use its lungs for respiration. However, this becomes lethal once the fetus is born and has to take its first breath. It is thought that NFIB plays a role in down regulating the transcription factors TGF-β1 and Shh in normal gestation because they remained high in knockout experiments.[9] The absence of NFIB also leads to insufficient amounts of surfactant being produced which is one reason why the mice cannot breathe once it is born.[9] The knockout experiments demonstrated that NFIB has a significant role in fore-brain development. NFIB is typically found in pontine nuclei of the CNS, the cerebral cortex and the white matter of the brain and without NFIB these areas are dramatically affected.[8][11]

Absence of one copy is associated with macrocephaly and intellectual disability. This associated was confirmed in mouse models where deletion of one copy resulted in enlargement of the brain while preserving its overall organisation.[12]

References

edit- ^ a b c GRCh38: Ensembl release 89: ENSG00000147862 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ a b c GRCm38: Ensembl release 89: ENSMUSG00000008575 – Ensembl, May 2017

- ^ "Human PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ "Mouse PubMed Reference:". National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine.

- ^ Qian F, Kruse U, Lichter P, Sippel AE (July 1995). "Chromosomal localization of the four genes (NFIA, B, C, and X) for the human transcription factor nuclear factor I by FISH". Genomics. 28 (1): 66–73. doi:10.1006/geno.1995.1107. PMID 7590749.

- ^ "Entrez Gene: NFIB nuclear factor I/B".

- ^ Schanze I, Bunt J, Lim JW, Schanze D, Dean RJ, Alders M, et al. (November 2018). "NFIB Haploinsufficiency Is Associated with Intellectual Disability and Macrocephaly". American Journal of Human Genetics. 103 (5): 752–768. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.10.006. PMC 6218805. PMID 30388402.

- ^ a b c Chaudhry AZ, Lyons GE, Gronostajski RM (March 1997). "Expression patterns of the four nuclear factor I genes during mouse embryogenesis indicate a potential role in development". Developmental Dynamics. 208 (3): 313–325. doi:10.1002/(sici)1097-0177(199703)208:3<313::aid-aja3>3.0.co;2-l. PMID 9056636.

- ^ a b c d Gründer A, Ebel TT, Mallo M, Schwarzkopf G, Shimizu T, Sippel AE, et al. (March 2002). "Nuclear factor I-B (Nfib) deficient mice have severe lung hypoplasia". Mechanisms of Development. 112 (1–2): 69–77. doi:10.1016/S0925-4773(01)00640-2. PMID 11850179. S2CID 10396584.

- ^ Database GH. "NFIB Gene - GeneCards | NFIB Protein | NFIB Antibody". www.genecards.org. Retrieved 2017-04-09.

- ^ a b Steele-Perkins G, Plachez C, Butz KG, Yang G, Bachurski CJ, Kinsman SL, et al. (January 2005). "The transcription factor gene Nfib is essential for both lung maturation and brain development". Molecular and Cellular Biology. 25 (2): 685–698. doi:10.1128/MCB.25.2.685-698.2005. PMC 543431. PMID 15632069.

- ^ Schanze I, Bunt J, Lim JW, Schanze D, Dean RJ, Alders M, et al. (November 2018). "NFIB Haploinsufficiency Is Associated with Intellectual Disability and Macrocephaly". American Journal of Human Genetics. 103 (5): 752–768. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.10.006. PMC 6218805. PMID 30388402.

Further reading

edit- Liu Y, Bernard HU, Apt D (April 1997). "NFI-B3, a novel transcriptional repressor of the nuclear factor I family, is generated by alternative RNA processing". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 272 (16): 10739–10745. doi:10.1074/jbc.272.16.10739. PMID 9099724.

- Geurts JM, Schoenmakers EF, Röijer E, Aström AK, Stenman G, van de Ven WJ (February 1998). "Identification of NFIB as recurrent translocation partner gene of HMGIC in pleomorphic adenomas". Oncogene. 16 (7): 865–872. doi:10.1038/sj.onc.1201609. PMID 9484777.

- Norquay LD, Yang X, Sheppard P, Gregoire S, Dodd JG, Reith W, et al. (June 2003). "RFX1 and NF-1 associate with P sequences of the human growth hormone locus in pituitary chromatin". Molecular Endocrinology. 17 (6): 1027–1038. doi:10.1210/me.2003-0025. PMID 12624117.

- Sheeter D, Du P, Rought S, Richman D, Corbeil J (February 2003). "Surface CD4 expression modulated by a cellular factor induced by HIV type 1 infection". AIDS Research and Human Retroviruses. 19 (2): 117–123. doi:10.1089/088922203762688621. PMID 12639247.

- Mukhopadhyay SS, Rosen JM (July 2007). "The C-terminal domain of the nuclear factor I-B2 isoform is glycosylated and transactivates the WAP gene in the JEG-3 cells". Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 358 (3): 770–776. doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.04.185. PMC 1942171. PMID 17511965.

External links

edit- NFIB+protein,+human at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

This article incorporates text from the United States National Library of Medicine, which is in the public domain.