Sirmur (also spelled as Sirmor, Sirmaur, Sirmour, or Sirmoor) was an independent kingdom in India, founded in 1616, located in the region that is now the Sirmaur district of Himachal Pradesh. The state was also known as Nahan, after its main city, Nahan. The state ranked predominant amongst the Punjab hill States. It had an area of 4,039 km2 and a revenue of 300,000 rupees in 1891.[citation needed]

| Sirmaur State Sirmoor State Nahan State | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Princely State of British India | |||||||

| 1095–1948 | |||||||

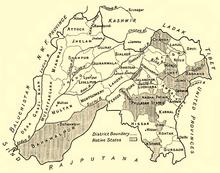

Sirmur State in a 1911 map of Punjab | |||||||

| Capital | Nahan | ||||||

| Area | |||||||

| 4,039 km2 (1,559 sq mi) | |||||||

| Population | |||||||

| 135,626 | |||||||

| History | |||||||

• Established | 1095 | ||||||

| 1948 | |||||||

| |||||||

| Today part of | Himachal Pradesh, India | ||||||

| Gazetteer of the Sirmur State. New Delhi: Indus Publishing. 1996. ISBN 978-81-7387-056-9. OCLC 41357468. | |||||||

History

editOrigin

editAccording to Mian Goverdhan Singh in Wooden Temples of Himachal Pradesh, the principality of Sirmaur was founded in the 7th to 8th century by Maharaja of Parmar Rajputs, and Rathore noble.[1]

Nahan State

editNahan, the predecessor state of Sirmur, was founded by Soba Rawal in 1095 AD who assumed the name Raja Subans Prakash.[citation needed]

Near the end of the 12th century in the year 1195, a flood of the Giri River destroyed the old capital of Sirmaur-Tal, which killed Raja Ugar Chand.[1] A ruler of Jaisalmer, Raja Salivahana, thought this was an opportune time to attack the state as it was in a state of disarray due to the natural disaster and death of its ruler, so he sent his son Sobha to conquer the state.[1] The attack was successful and a new dynasty headed by Bhati Rajputs was established.[1] Sirmur was invaded by invader Jasrath's army, who also invaded fragments of Punjab and Jammu.[2]

Sirmur State

editThe new capital was founded in 1621 by Raja Karam Prakash, and the state was renamed to Sirmur.[citation needed]

Sirmur was surrounded by the hill states of Balsan and Jubbal in the North, Dehradun district in the East, Ambala district in the South West, and the states of Patiala and Keonthal in the North-West.[citation needed]

But by chance, shortly after this event a prince of Jaisalmer visited Haridwar as a pilgrim, and was invited by one of the minstrels of the Sirmoor kingdom to become its sovereign.[citation needed] He accordingly sent a force under his son, the Rawal or prince Sobha, who put down the disorders which had arisen in the state, and became the first Räjã of Sirmur, under the title of Subhans Parkash, a title which the Rajãs have ever since retained.[citation needed]

Rajban became the capital of the new king in 1095.[citation needed] The eighth Rãjã conquered Ratesh, later a part of the Keonthal State, about 1150 and his successor subdued Jubbal, Balsan, Kumharsain, Ghond, Kot, and Theog, thus extending his dominions almost to the Sutlej.[citation needed] For many years these territories remained feudatories of the State; but its capital was at Kälsi, in Dehra Dun, and the Rajas’ hold over their northern fiefs appears to have been weak until in the fourteenth century Bir Parkash fortified Hãth-Koti, on the confines of Jubbal, Retwain, and Sahri, the last of which became the capital of the State for a time.[citation needed]

Eventually in 1621 Karm Parkash founded Nahan, the modern capital.[citation needed] His successor, Mandhata, was called upon to aid Khalil-ullah, the general of the emperor Shah Jahan, in his invasion of Garhwãl, and his successor, Sobhag Parkãsh, received a grant of Kotaha in reward for this service.[citation needed] Under Aurangzeb this Rãjä again joined in operations against Garhwãl.[citation needed] His administration was marked by a great development of the agricultural resources of the State, and the tract of Kolagarh was also entrusted to him by the emperor.[citation needed]

Budh Parkãsh, the next ruler, recovered Pinjaur for Aurangzeb’s foster-brother.[citation needed] Raja Mit Parkãsh gave an asylum to the Sikh Guru, Gobind Singh, permitting him to fortify Paonta in the Kiarda Dun; and it was at Bhangani in the Dun that the Guru defeated the Rajäs of Kahlur and Garhwäl in 1688.[citation needed] But in 1710 Kirat Parkãsh, after defeating the Räja of Garhwal, captured Naraingarh, Morni, Pinjaur, and other territories from the Sikhs, and concluded an alliance with Amar Singh, Raja of Patiala, whom he aided in suppressing his rebellious Wazir; and he also fought in alliance with the Raja of Kahlür when Ghuläm Kãdir Khan, Rohilla, invaded that State.[citation needed] He supported the Rajã of Garhwãl in his resistance to the Gurkha invasion, and, though deserted by his ally, was able to compel the Gurkhas to agree to the Ganges as the boundary of their dominions.[citation needed] His son, Dharm Parkãsh, repulsed the encroachments of the chief of Nalagarh and an invasion by the Rãjã of Garhwãl, only to fall fighting in single combat with Rãjã Sansãr Chand of Kangra who had invaded Kalhur, in 1793.[citation needed]

Gurkha occupation

editHe was succeeded by his brother, Karm Parkãsh, a weak ruler, whose misconduct caused a serious revolt. To suppress this he rashly invoked the aid of the Gurkhas, who promptly seized their opportunity and invaded Sirmür, expelled Ratn Parkash, whom the rebels had placed on the throne, and then refused to restore Karm Parkash.[citation needed] His queen, a princess of Goler and a lady of courage and resource, took matters into her own hands and invoked British aid.[citation needed] Her appeal coincided with the declaration of war against Nepal by the British, and a force was sent to expel the Gurkhas from Sirmür.[citation needed]

Colonial-period

editOn the conclusion of the Gurkha War the British Government placed Fateh Parkash, the minor son of Karm Parkãsh, on the throne, annexing all the territories east of the Jumna with Kotaha and the Kiãrda Dan.[citation needed] The Dun was, however, restored to the State in 1833 on payment of Rs.50,000.[citation needed] During the first Afghan War the Raja aided the British with a loan, and in the first Sikh War a Sirmur contingent fought at Hari-ka-pattan.[citation needed] Under Raja Sir Shamsher Parksh, G.C.S.I. (1856—98), the State progressed rapidly.[citation needed] Begar (forced labour) was abolished, roads were made, revenue and forest settlements carried out, a foundry, dispensaries, post and telegraph offices established.[citation needed] In 1857 the Raja rendered valuable services, and in 1880 during the Second Afghan War he sent a contingent to the north-west frontier.[citation needed] The Sirmür Sappers and Miners under his second son, Major Bir Bikram Singh, C.I.E., accompanied the Tirãh expedition in 1897.[3]

Rulers

editThe rulers of Sirmur bore the title "Maharaja" from 1911 onward.[4]

| Name | Portrait | Ruled from | Ruled until | Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subhansh Prakash | 1095 | 1099 | ||

| Mahe Prakash | 1099 | 1117 | ||

| Udit Prakash | 1117 | 1127 | ||

| Kaul Prakash | 1127 | 1153 | ||

| Sumer Prakash | 1153 | 1188 | ||

| Suraj Prakash | 1188 | 1254 | ||

| Bhagat Prakash I | 1254 | 1336 | ||

| Jagat Prakash | 1336 | 1388 | ||

| Bir Prakash | 1388 | 1398 | ||

| Naket Prakash | 1398 | 1398 | ||

| Ratna Prakash | 1398 | 1413 | ||

| Garv Prakash | 1413 | 1432 | ||

| Brahm Prakash | 1432 | 1446 | ||

| Hams Prakash | 1446 | 1471 | ||

| Bhagat Prakash II | 1471 | 1538 | ||

| Dharam Prakash | 1538 | 1570 | ||

| Deep Prakash | 1570 | 1585 | ||

| Budh Prakash | 1605 | 1615 | ||

| Bhagat Prakash III | 1615 | 1620 | ||

| Karam Prakash I | 1621 | 1630 | ||

| Mandhata Prakash | 1630 | 1654 | ||

| Sobhag Prakash | 1654 | 1664 | ||

| Budh Prakash | 1664 | 1684 | [1][5] | |

| Mat Prakash | 1684 | 1704 | [1][5] | |

| Hari Prakash | 1704 | 1712 | [5] | |

| Bijay Prakash | 1712 | 1736 | ||

| Pratap Prakash | 1736 | 1754 | ||

| Kirat Prakash | 1754 | 1770 | ||

| Jagat Prakash | 1770 | 1789 | ||

| Dharam Prakash | 1789 | 1793 | ||

| Karam Prakash II (died 1820) | 1793 | 1803 | ||

| Ratan Prakash (installed by Gurkhas, hanged by the British in 1804) | 1803 | 1804 | ||

| Karma Prakash II (died 1820) | 1804 | 1815 | ||

| Fateh Prakash | 1815 | 1850 | ||

| Raghbir Prakash | 1850 | 1856 | ||

| Shamsher Prakash | 1856 | 1898 | ||

| Surendra Bikram Prakash | 1898 | 1911 | ||

| Amar Prakash | 1911 | 1933 | ||

| Rajendra Prakash | 1933 | 1947 |

Demographics

edit| Religious group |

1901[6] | 1911[7][8] | 1921[9] | 1931[10] | 1941[11] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | Pop. | % | |

| Hinduism [a] | 128,478 | 94.69% | 130,276 | 94.05% | 132,431 | 94.29% | 139,031 | 93.58% | 146,199 | 93.7% |

| Islam | 6,414 | 4.73% | 6,016 | 4.34% | 6,449 | 4.59% | 7,020 | 4.73% | 7,374 | 4.73% |

| Sikhism | 688 | 0.51% | 2,142 | 1.55% | 1,449 | 1.03% | 2,413 | 1.62% | 2,334 | 1.5% |

| Jainism | 61 | 0.04% | 49 | 0.04% | 65 | 0.05% | 52 | 0.04% | 81 | 0.05% |

| Christianity | 46 | 0.03% | 37 | 0.03% | 44 | 0.03% | 52 | 0.04% | 38 | 0.02% |

| Buddhism | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 10 | 0.01% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Zoroastrianism | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Judaism | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Others | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% | 0 | 0% |

| Total population | 135,687 | 100% | 138,520 | 100% | 140,448 | 100% | 148,568 | 100% | 156,026 | 100% |

| Note: British Punjab province era district borders are not an exact match in the present-day due to various bifurcations to district borders — which since created new districts — throughout the historic Punjab Province region during the post-independence era that have taken into account population increases. | ||||||||||

Artwork

editNot many paintings depicting the historical rajas of Sirmur State have survived due to the Gurkha occupation of the state between 1803–14, which led to the loss and destruction of much artwork, including any portraits of earlier rulers produced in Sirmur itself.[12][13]

Notes

edit- ^ 1931-1941: Including Ad-Dharmis

References

edit- ^ a b c d e f Singh, Mian Goverdhan (1999). Wooden Temples of Himachal Pradesh. Indus Publishing. pp. 48–49. ISBN 9788173870941.

- ^ Panikkar, Ayyappa (1997). Medieval Indian Literature: Surveys and selections. Sahitya Akademi. p. 72. ISBN 978-81-260-0365-5.

- ^ "Imperial Gazetteer of India, v. 23, p. 22". Retrieved 9 January 2012.

- ^ Princely states of India

- ^ a b c Archer, William George (1973). Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills. Indian Paintings from the Punjab Hills: A Survey and History of Pahari Miniature Painting. Vol. 1. Sotheby Parke Bernet. p. 414. ISBN 9780856670022.

- ^ "Census of India 1901. [Vol. 17A]. Imperial tables, I-VIII, X-XV, XVII and XVIII for the Punjab, with the native states under the political control of the Punjab Government, and for the North-west Frontier Province". 1901. p. 34. JSTOR saoa.crl.25363739. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1911. Vol. 14, Punjab. Pt. 2, Tables". 1911. p. 27. JSTOR saoa.crl.25393788. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Kaul, Harikishan (1911). "Census Of India 1911 Punjab Vol XIV Part II". p. 27. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1921. Vol. 15, Punjab and Delhi. Pt. 2, Tables". 1921. p. 29. JSTOR saoa.crl.25430165. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India 1931. Vol. 17, Punjab. Pt. 2, Tables". 1931. p. 277. JSTOR saoa.crl.25793242. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ "Census of India, 1941. Vol. 6, Punjab". 1941. p. 42. JSTOR saoa.crl.28215541. Retrieved 30 March 2024.

- ^ Plumbly, Sara (2020). "RAJA JAGAT PRAKASH OF SIRMUR (R.1770-89) WORSHIPPING RAMA AND SITA". Christie's. Retrieved 23 October 2024.

Very few portraits of Sirmur rulers remain as the Gurkha occupation of the state in 1803-14 is thought to have destroyed any earlier paintings.

- ^ Galloway, Francesca. Pahari Paintings From the Eva and Konrad Seitz Collection (PDF). www.francescagalloway.com. p. 48.