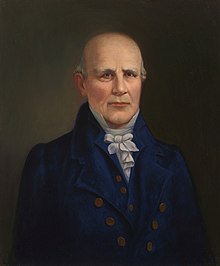

Nathaniel Macon (December 17, 1757 – June 29, 1837) was an American politician who represented North Carolina in both houses of Congress. He was the fifth speaker of the House, serving from 1801 to 1807. He was a member of the United States House of Representatives from 1791 to 1815 and a member of the United States Senate from 1815 to 1828. He opposed ratification of the United States Constitution and the Federalist economic policies of Alexander Hamilton. From 1826 to 1827, he served as President pro tempore of the United States Senate. Thomas Jefferson dubbed him "Ultimus Romanorum"—"the last of the Romans".

During his political career he was spokesman for the Old Republican faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that wanted to strictly limit the United States federal government. Along with fellow Old Republicans John Randolph and John Taylor, Macon frequently opposed various domestic policy proposals, and generally opposed the internal improvements promoted by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun.

An earnest defender of slavery, Macon voted against the Missouri Compromise in 1820. In the 1824 presidential election, he received several electoral votes for vice president, despite declining to run, as the stand-in running-mate for William Harris Crawford. He also served as president of the 1835 North Carolina constitutional convention.

After leaving public office, he served as a trustee for the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and protested President Andrew Jackson's threat to use force during the Nullification Crisis.

Early life

editNathaniel Macon was born near Warrenton, North Carolina, the son of Maj. Gideon Macon, a Virginia native, and North Carolina-born Priscilla Jones, and through his great-grandfather, Col. Gideon Macon, an English citizen of allegedly French Huguenot background,[1][2] Nathaniel was second cousin of First Lady Martha Dandridge Washington.[3][4]

Maj. Gideon Macon had built "Macon Manor" and became a prosperous tobacco planter, where Nathaniel was born as the sixth child of Gideon and Priscilla, and he was only two when his father died in 1761. Upon his death, Gideon possessed 3,000 acres (12 km2) of land and 25–30 slaves.[5][6] Nathaniel was bequeathed two parcels of land and all of his father's blacksmithing tools. Gideon also left his son three slaves: George, Robb, and Lucy.[7]

Education

editIn 1766, Priscilla (Jones) Macon, now the wife of James Ransom,[5] arranged for the education of two of her sons, Nathaniel and John, along with the two sons of her neighbor Philemon Hawkins II. For this purpose, they engaged Mr. Charles Pettigrew, who later became the principal of the Academy of Edenton in 1733. The two brothers and their neighbors, Joseph and Benjamin Hawkins, later a senator and U. S. Indian agent, were instructed by him from 1766 to 1773.[8]

Three of the four boys (Nathaniel and Benjamin among them) continued on to further their education at the "College of New Jersey" at Princeton as part of the class of 1777.[9][10] Neither Nathaniel or Benjamin would graduate.[11]

American Revolution

editMacon performed a short term of military duty during the American Revolution.[12] He returned to North Carolina in the fall of 1776, and studied law for three years. He rejoined the Revolution as a private in 1780, and was likely present at the Battle of Camden.[13]

Marriage and family

editMacon met Hannah Plummer in 1782 in Warrenton, North Carolina. Her parents William Plummer and Mary Hayes were Virginians like Macon's, and they were "well connected".[14] Macon was a tall man, over 6 feet (1.8 m), and considered attractive, but he was not the only man who was pursuing Miss Plummer. However, after a number of months of courtship, Hannah and Nathaniel decided to marry.

One story often told of her courtship involves Macon challenging an unnamed potential suitor to a card game, with Hannah Plummer as the prize. The offer was accepted, and Macon lost the card game. Upon losing, he turned to Hannah and exclaimed "notwithstanding I have lost you fairly—love is superior to honesty—I cannot give you up." This won her favor, and they were married soon afterwards.[15] Their wedding took place on October 9, 1783, and their marriage was an affectionate one.

In laws

editHer brother was the lawyer Kemp Plummer, the grandfather of Kemp Plummer Battle. Kemp Plummer and Nathaniel Macon were both part of the "Warren Junto" which also included James Turner, Weldon Edwards, William Hawkins, and William Miller, all of whom dominated North Carolina political life at that time.[16] Kemp Plummer was the second owner of the oldest house in Warrenton. The original owner was Marmaduke Johnson, who married Macon's half-sister Hixie Ransom.[17] Another Plummer brother was William Plummer II, who married Macon's half-sister Betsy Ransom.[18][19]

Children, death, and burial

editAccording to Bible records, the Macons had three children:

- Betsy Kemp Macon (September 12, 1784 – November 10, 1829) married William John Martin (March 6, 1781 – December 11, 1828)

- Plummer Macon (April 14, 1786 – July 26, 1792)

- Seignora Macon (November 15, 1787 – August 16, 1825) married William Eaton[20]

Macon's wife, Hannah, died on July 11, 1790, when she was just 29 years old. Although Nathaniel was only 32 at the time of her death, he never remarried.[21] It is said that he was devoted to his wife, and his long unmarried life following her early death would suggest that he was faithful to her memory.

Her remains were buried not far from their home on the borders of their yard. Their only son died just over a year after Hannah and was buried beside her. When Nathaniel died July 29, 1837, at age 79, he was laid to rest next to his wife and son. As he requested, the site of their graves was covered with a great heap of flint stones so that the land would be left uncultivated; Macon believed that no one would go to the trouble of removing all of the flint in order to use the land, thereby preserving the burial site.

Buck Spring Plantation

editMacon and his wife made their home on Hubquarter Creek on their plantation known as "Buck Spring Plantation". Macon's father Gideon's will bequeathed to him lands on Shocco Creek and "Five hundred acres of Land lying and being on both sides of Hubquarter Creek".[7] It was about 12 miles (19 km) north of Warrenton, near Roanoke Rapids.[21] His plantation grew to 1,945 acres, served by 70 slaves, with whom he often worked together in the fields, as well as serving as justice of the peace and a trustee of the Warrenton Academy. He raised thoroughbred race horses and had a pack of fox hounds, in 1819 hosting President Monroe for a hunt.

Political life

editHe served in the North Carolina Senate for Warren County in 1781, 1782, and 1784.[23]

Macon opposed the Constitution and spent his four decades in Congress making sure the national government would remain weak. He was for 37 years the most prominent nay-sayer in Congress—a "negative radical".[24] It was said of him that during the entire term of his service no other members cast so many negative votes. "Negation was his word and arm."

He was rural and local-minded, and economy was the passion of his public career. "His economy of the public money was the severest, sharpest, most stringent and constant refusal of almost any grant that could be proposed." With him, "not only was ... parsimony the best subsidy—but ... the only one".[25]

He supported all of the foreign policies of Jefferson and Madison from 1801 to 1817. Macon detested Alexander Hamilton and the Federalist program.

1791 to 1799

editHe was especially hostile to a navy, fearing the expense would create a financial interest. He bitterly opposed the Jay Treaty in 1795, the Alien and Sedition Acts of 1798, and the movement for war with France in 1798–99. Macon supported the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions.[26]

1800 to 1809

editMacon served as Speaker of the House from 1801 to 1807. He was the fifth person, and first Southerner to serve in the office.[27] He supported the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, and tried to get Jefferson to purchase Florida as well. Jefferson offered the post of postmaster general to Macon at least twice, but he declined.[28]

During his second term as speaker, Macon broke with Jefferson, believing that the president had strayed from the fundamental principles of Republicanism – strict constitutional construction and state sovereignty, and began collaborating more with John Randolph and John Taylor as part of the splinter Quids faction of the Democratic-Republican Party.[29] Even so, he still narrowly won a third term.

He did not seek a fourth term as speaker when the 10th Congress convened in 1807. Instead he chaired the Foreign Relations Committee.[28]

1810 to 1819

editMacon Bill No. 1 attacked British shipping, but was defeated. In May 1810, Macon's Bill No. 2 was passed, giving the president power to suspend trade with either Great Britain or France if the other should cease to interfere with United States commerce. Macon neither wrote nor approved of Bill No. 2. [30] Macon supported Madison in declaring the War of 1812; he opposed conscription to build the army and opposed higher taxes.

He did favor some road construction by the federal government, but generally opposed the policy of internal improvements promoted by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun. He opposed the recharter of the United States Bank in 1811 and in 1816, uniformly voted against any form of protective tariff.

1820 to 1828

editHe was always an earnest defender of slavery. In the Missouri debate of 1820 he voted against the compromise brokered by Clay. Macon was also considered a potential candidate for the presidency in 1824 but declined. Macon won 24 electoral votes for vice president as the stand-in running-mate for William Harris Crawford. Macon was asked to run for the vice presidency again in 1828 but declined.

After retirement

editAmong his other public acts in retirement were writing a letter in 1832 to President Jackson protesting the threatened use of military action to quell the South Carolina nullifiers. He wrote to Samuel P. Carson that he believed in the right of secession: "A government of opinion established by sovereign States for special purposes can not be maintained by force."[31]

He served as President of the 1835 convention to amend and reform the Constitution of North Carolina. The resulting amendments to the state constitution mostly related to political reform and greater democracy. He was largely opposed to the amendments that were adopted.[32] He also served as a trustee of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, and supported Martin Van Buren in the election of 1836.[33]

Places named after Nathaniel Macon

editReferences

edit- Specific

- ^ Dodd (1903), p. 2

- ^ McCormick, James Gilchrist; Battle, Kemp Plummer (1900). Personnel of the Convention of 1861. University Press. p. 39.

- ^ Brady, Patricia (May 30, 2006). Martha Washington: An American Life. Penguin. ISBN 9781101118818.

- ^ Virginia Gleanings in England: Abstracts of 17th and 18th-century English Wills and Administrations Relating to Virginia and Virginians : A Consolidation of Articles from the Virginia Magazine of History and Biography. Genealogical Publishing Com. May 4, 1980. ISBN 978-0-8063-0869-2.

- ^ a b Dodd (1903), p. 3

- ^ "Slaves of Nathaniel Macon".

- ^ a b Will of Gideon Macon, Granville County Wills: Unrecorded Wills, 1746-1771, Archives Section, Department of Cultural Resources, Raleigh, North Carolina

- ^ Dodd (1903), p. 4

- ^ Cotten (1840) p. 29

- ^ Pound, Merritt B. (August 2009). Benjamin Hawkins, Indian Agent. University of Georgia Press. ISBN 9780820334516.

- ^ Collins, Varnum Lansing (1914). Princeton. Oxford University Press, American branch. p. 96.

- ^ Edwards, Weldon Nathaniel (1862). Memoir of Nathaniel Macon, of North Carolina. Raleigh Register Steam Power Press.

- ^ Dodd (1903), p. 28; 32

- ^ Dodd (1903), p. 41

- ^ Cotten (1840) p. 55-56

- ^ Powell, William S. (November 9, 2000). Dictionary of North Carolina Biography: Vol. 5, P-S. Univ of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807867006 – via Google Books.

- ^ "The Marmaduke Johnson House: A Warren County (and national) treasure hidden in plain sight". The Warren Record. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- ^ Groves, Joseph Asbury (1901). The Alstons and Allstons of North and South Carolina. Franklin printing and publishing Company. pp. 512–515.

- ^ Wellman (2002) p. 62

- ^ Dodd (1903), p. 44

- ^ a b Southwick, Leslie H. (January 1, 1998). Presidential Also-rans and Running Mates, 1788 Through 1996. McFarland & Company. ISBN 9780786403103.

- ^ Wellman 2002, p. 58-59

- ^ Wheeler, John H. (1874). "The Legislative Manual and Political Register of the State of North Carolina". Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ Hamilton 1933.

- ^ C. J. Ingersoll, quoted Hamilton 1933.

- ^ Dodd (1902) p. 666

- ^ Follett, Mary Parker (1909) [First edition, 1896]. The speaker of the House of Representatives. New York, New York: Longmans, Greene, and Company. p. 68. Retrieved March 8, 2019 – via Internet Archive, digitized in 2007.

- ^ a b Glass, Andrew (June 29, 2016). "Nathaniel Macon, former speaker, dies, June 29, 1837". Politico. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ Starnes, Richard D. (2006). "Quids". NCpedia. Encyclopedia of North Carolina, University of North Carolina Press. Retrieved March 12, 2019.

- ^ Garry Wills (2002). James Madison: The American Presidents Series: The 4th President, 1809-1817. Macmillan. p. 87. ISBN 9780805069051.

- ^ Dodd (1902) p. 668

- ^ North Carolina History Project

- ^ Dodd (1902) p. 664

- General

- Cotten, Edward R. Life of the Hon. Nathaniel Macon. Baltimore: Printed by Lucas & Deaver, 1840.

- Dodd, William Edward (1903). The Life of Nathaniel Macon. Edwards & Broughton. OCLC 10971454., pp. 1–4; 41–44.

- Dodd, William E. (1902). "The Place of Nathaniel Macon in Southern History". American Historical Review. 7 (4): 663–675. doi:10.2307/1834563. JSTOR 1834563.

- Hamilton, J. G. de Roulhac. "Macon, Nathaniel" in Dictionary of American Biography, Volume 6 (1933)

- Wellman, Manly Wade (2002). The County of Warren, North Carolina, 1586-1917. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 978-0-8078-5472-3.