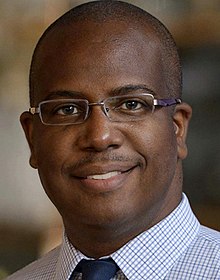

Neil Hanchard is a Jamaican physician and scientist who is clinical investigator in the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), where he leads the Childhood Complex Disease Genomics section.[1] Prior to joining NHGRI, he was an associate professor of molecular and human genetics at the Baylor College of Medicine.[2] He is a fellow of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics, .[1][3][4] Hanchard's research focuses on the genetics of childhood disease, with an emphasis on diseases impacting global health.[2]

Early life and education

editHanchard grew up in Jamaica.[3] In 1999, he received a Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery degree from the University of the West Indies in Kingston, Jamaica. He then studied at the University of Oxford as a Rhodes Scholar.[1][5] He received a Doctor of Philosophy degree from Oxford in 2004, and completed a residency in pediatrics at the Mayo Clinic in 2009. Subsequently, he completed a clinical fellowship in clinical genetics at the Baylor College of Medicine.[2]

Research

editHanchard's research focuses on genetic factors that can lead children to manifest especially severe symptoms of malnutrition,[6] genomics of disease progression in children with HIV and tuberculosis, and genetic factors that contribute to comorbidities in sickle cell disease.[2] He is a member of the Undiagnosed Diseases Network, and is interested in identifying molecular diagnoses for children with uncommon genetic disease symptoms.[2]

In collaboration with the Human Heredity and Health in Africa (H3Africa) consortium, he was a senior author on a publication surveying human genetic diversity in Africa.[7][8][9] The study was published in and featured on the cover of Nature, which described the work as "a milestone in genomics research".[10][11] In this work, they sequenced the complete genomes of 426 African individuals who belonged to 50 distinct ethnolinguistic groups, including individuals from populations that had never previously been sequenced.[8][12] The study revealed previously unknown historical human migration patterns, for example leading to insight into the history of the Berom people of Nigeria.[9] It identified more than 3 million genetic variants that had not been previously observed, which could contribute to making genetic tests more accurate for people with African ancestry.[9][8]

He has coauthored more than 70 peer reviewed articles. His papers have appeared in Nature, Science, and the American Journal of Human Genetics.[1]

Personal life

editHanchard is married with children.[3]

Selected publications

edit- Choudhury, A., Aron, S., Botigué, L.R. et al. High-depth African genomes inform human migration and health. Nature 586, 741–748 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-020-2859-7

- Schulze, K.V., Bhatt, A., Azamian, M.S. et al. Aberrant DNA methylation as a diagnostic biomarker of diabetic embryopathy. Genet Med 21, 2453–2461 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41436-019-0516-z

- Schulze, K.V., Swaminathan, S., Howell, S. et al. Edematous severe acute malnutrition is characterized by hypomethylation of DNA. Nat Commun 10, 5791 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-019-13433-6

- Retshabile, G, Mlotshwa, B.C.,Williams, L et al. Whole-Exome Sequencing Reveals Uncaptured Variation and Distinct Ancestry in the Southern African Population of Botswana. Am J Hum Genet. 102 (5), 731-743 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.03.010

- Hanchard NA, Swaminathan S, Bucasas K et al. A genome-wide association study of congenital cardiovascular left-sided lesions shows association with a locus on chromosome 20. Hum Mol Genet. 25 (11), 2331-2341 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddw071

- Hanchard NA, Rockett KA, Spencer C, et al. Screening for recently selected alleles by analysis of human haplotype similarity. Am J Hum Genet. 78 (1), 153-9 (2006). https://doi.org/10.1086/499252

External links

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d "Dr. Neil Hanchard joins NHGRI as a clinical investigator". Genome.gov. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Neil Hanchard, M.D., Ph.D." Baylor College of Medicine. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Cullinan, Sara (30 May 2018). "Inside AJHG: A Chat with Neil Hanchard". ASHG. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ "Advisory Board: Cell Genomics: Cell Genomics". www.cell.com. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "UWI Rhodes Scholars". UWI Alumni Online. 10 July 2010. Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Schulze, Katharina V.; Swaminathan, Shanker; Howell, Sharon; Jajoo, Aarti; Lie, Natasha C.; Brown, Orgen; Sadat, Roa; Hall, Nancy; Zhao, Liang; Marshall, Kwesi; May, Thaddaeus (19 December 2019). "Edematous severe acute malnutrition is characterized by hypomethylation of DNA". Nature Communications. 10 (1): 5791. Bibcode:2019NatCo..10.5791S. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-13433-6. ISSN 2041-1723. PMC 6923441. PMID 31857576.

- ^ "New Genome Sequences Reveal Undescribed African Migration". The Scientist Magazine®. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ a b c Qaiser, Farah. "Genome Analysis Of 426 Africans Finds Over 3 Million New Variants". Forbes. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ a b c "'Unprecedented' analysis underlines past failures to study African genomes". STAT. 16 October 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Volume 586 Issue 7831, 29 October 2020". www.nature.com. Retrieved 16 February 2021.

- ^ "Africa's people must be able to write their own genomics agenda". Nature. 586 (7831): 644. 28 October 2020. Bibcode:2020Natur.586..644.. doi:10.1038/d41586-020-03028-3. PMID 33116292.

- ^ Choudhury, Ananyo; Aron, Shaun; Botigué, Laura R.; Sengupta, Dhriti; Botha, Gerrit; Bensellak, Taoufik; Wells, Gordon; Kumuthini, Judit; Shriner, Daniel; Fakim, Yasmina J.; Ghoorah, Anisah W. (28 October 2020). "High-depth African genomes inform human migration and health". Nature. 586 (7831): 741–748. Bibcode:2020Natur.586..741C. doi:10.1038/s41586-020-2859-7. ISSN 1476-4687. PMC 7759466. PMID 33116287.