This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (September 2011) |

Nikolai Vasilyevich Krylenko (Russian: Никола́й Васи́льевич Крыле́нко, IPA: [krɨˈlʲenkə]; 2 May 1885 – 29 July 1938) was an Old Bolshevik and Soviet politician, military commander, and jurist. Krylenko served in a variety of posts in the Soviet legal system, rising to become People's Commissar for Justice and Prosecutor General of the Russian Soviet Federated Socialist Republic. He was executed during the Great Purge.

Nikolai Krylenko | |

|---|---|

| Николай Крыленко | |

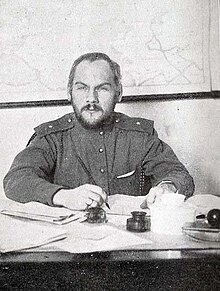

Krylenko in 1918 | |

| People's Commissar for Justice of the USSR | |

| In office 20 July 1936 – 15 September 1937 | |

| Premier | Vyacheslav Molotov |

| Preceded by | None—position established |

| Succeeded by | Nikolay Rychkov |

| Prosecutor General of the Russian SFSR | |

| In office May 1929 – 5 May 1931 | |

| Premier | Alexey Rykov Vyacheslav Molotov |

| Preceded by | Nikolai Janson |

| Succeeded by | Andrey Vyshinsky |

| Chairman of the Supreme Court of the Soviet Union | |

| In office 28 November 1923 – 2 February 1924 | |

| Succeeded by | Alexander Vinokurov |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 2 May 1885 Bekhteevo, Sychyovsky Uyezd, Smolensk Governorate, Russian Empire |

| Died | 29 July 1938 (aged 53) Moscow, Russian SFSR, Soviet Union |

| Political party | RSDLP (Bolsheviks) (1904–1918) Russian Communist Party (1918–1938) |

| Spouse | Elena Rozmirovich |

| Relations | Elena Krylenko (sister) |

| Occupation | Lawyer, theorist, writer |

Krylenko was an exponent of socialist legality and the theory that political considerations, rather than criminal guilt or innocence, should guide the application of punishment. Although participating in the Show Trials and political repression of the late 1920s and early 1930s, Krylenko was later caught up as a victim and arrested during the Great Purge of the late 1930s. Following interrogation and torture[citation needed] by the NKVD, Krylenko confessed to extensive involvement in wrecking and anti-Soviet agitation. After a trial of 20 minutes, he was sentenced to death by the Military Collegium of the Soviet Supreme Court, and executed immediately afterwards.

Biography

editEarly life and education

editKrylenko was born in Bekhteyevo, in Sychyovsky Uyezd of Smolensk Governorate, the eldest of six children (two sons and four daughters) born to a populist revolutionary and his wife. His father, needing income to support his growing family, became a tax collector for the Tsarist government.[1]

The young Krylenko joined the Bolshevik faction of the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP) in 1904 while studying history and literature at St. Petersburg University, where he was known to fellow students as Comrade Abram. He was a member of the short-lived Saint Petersburg Soviet during the Russian Revolution of 1905 and a member of the Bolshevik Saint Petersburg Committee. He had to flee Russia in June 1906, but returned later that year. Arrested by the Tsar's secret police in 1907, Krylenko was released for lack of evidence, but soon exiled to Lublin (present-day Poland) without trial.

Krylenko returned to Saint Petersburg in 1909 and finished his degree. He left the RSDLP in 1911, but soon rejoined it. He was drafted in 1912 and was promoted to second lieutenant before being discharged in 1913. After working as an assistant editor of Pravda and a liaison to the Bolshevik faction in the Duma for a few months, Krylenko was arrested again in 1913 and exiled to Kharkiv. There he studied and earned a law degree. In early 1914, Krylenko learned that he might be re-arrested and fled to Austria.

At the outbreak of the Great War in August 1914, he moved to neutral Switzerland as a Russian national. In mid-1915, Vladimir Lenin sent Krylenko back to Russia to help rebuild the Bolshevik underground organization. In November 1915, Krylenko was arrested in Moscow as a draft dodger and, after a few months in prison, sent to the South West Front in April 1916.

1917 revolutions

editAfter the February Revolution of 1917 and the introduction of elected committees in the Russian armed forces, Krylenko was elected chairman of his regiment's and then division's committee. On 15 April, he was elected chairman of the 11th Army's committee. After Lenin's return to Russia in April 1917, Krylenko adopted the new Bolshevik policy of irreconcilable opposition to the Provisional Government. He had to resign his post on 26 May 1917 for lack of support from non-Bolshevik members of the Army committee.

In June 1917, Krylenko was made a member of the Bolshevik Military Organization and was elected to the First All-Russian Congress of Soviets. At the Congress, he was elected to the permanent All-Russian Central Executive Committee from the Bolshevik faction. Krylenko left Petrograd for the High Command HQ in Mogilev on 2 July, but was arrested there by the Provisional government after the Bolsheviks staged an abortive uprising on 4 July. He was kept in prison in Petrograd, but was released in mid-September after the Kornilov Affair.

Krylenko took an active part in preparing the October Revolution of 1917 in Petrograd as newly elected chairman of the Congress of Northern Region Soviets and a leading member of the Military Revolutionary Committee. On 16 October, ten days before the uprising, he reported to the Bolshevik Central Committee that the Petrograd military would support the Bolsheviks in case of an uprising. During the Bolshevik takeover on 24–25 October, Krylenko was one of the uprising's leaders, along with Leon Trotsky, Adolph Joffe, and Vladimir Antonov-Ovseenko.

Head of the Red Army

editAt the Second All Russian Congress of Soviets on 25 October, Krylenko was made a People's Commissar (minister) and member of the triumvirate (with Pavel Dybenko and Nikolai Podvoisky) responsible for military affairs. In early November (Old Style) 1917, immediately after the Bolshevik seizure of power, Krylenko helped Leon Trotsky suppress an attempt by Provisional Government loyalists, led by Alexander Kerensky and General Peter Krasnov, to retake Petrograd.

After the Provisional Commander in Chief (and Chief of General Staff), General Nikolai Dukhonin, refused to open peace negotiations with the Germans, Krylenko (an Ensign at this point) was appointed as Commander in Chief on 9 November. He started negotiations with representatives of the German army on 12–13 November. Krylenko arrived at the High Command HQ in Mogilev on 20 November and arrested General Dukhonin, who was bayoneted and shot to death by Red Guards answering to Krylenko.[2] After the formation of the Red Army on 15 January [O.S. 28 January] 1918, Krylenko was a member of the All-Russian Collegium that oversaw its buildup. He proved to be an excellent public speaker, able to win over hostile mobs with words alone.[2] His organizational talents, however, lagged far behind his oratorical ones.

Krylenko supported the policy of democratization of the Russian military, including abolishing subordination, providing for election of officers by enlisted men, and using propaganda to win over enemy units. Although the Red Army had some successes in early 1918 against small and poorly armed anti-Bolshevik detachments, the policy proved unsuccessful when Soviet forces were roundly defeated by the Imperial German Army in late February 1918 after the breakdown of the Brest-Litovsk negotiations.

In his 1918 essay Scythians?, Yevgeny Zamyatin, an Old Bolshevik who is now considered the first Soviet dissident cited Krylenko as an example of the ugliness and repression within the new Soviet Union. Zamyatin wrote, "Christ on Golgotha, between two thieves, bleeding to death drop by drop, is the victor – because he has been crucified, because, in practical terms, he has been vanquished. But Christ victorious in practical terms is the Grand Inquisitor. And worse, Christ victorious in practical terms is a paunchy priest in a silk-lined purple robe, who dispenses benedictions with his right hand and collects donations with his left. The Fair Lady, in legal marriage, is simply Mrs. So-and-So, with hair curlers at night and a migraine in the morning. And Marx, having come down to earth, is simply a Krylenko. Such is the irony and such is the wisdom of fate. Wisdom because this ironic law holds the pledge of eternal movement forward. The realization, materialisation, practical victory of an idea immediately gives it a philistine hue. And the true Scythian will smell from a mile away the odor of dwellings, the odor of cabbage soup, the odor of the priest in his purple cassock, the odor of Krylenko – and will hasten away from the dwellings, into the steppe, to freedom."[3]

Later in the same essay, Zamyatin quoted a recent poem by Andrei Bely and used it to further criticize Krylenko and those like him, for having, "covered Russia with a pile of carcasses," and for, "dreaming of socialist–Napoleonic wars in Europe – throughout the world, throughout the universe! But let us not jest incautiously. Bely is honest, and did not intend to speak about the Krylenkos."[4]

In the wake of the defeats, Trotsky pushed for the formation of a military council of former Russian generals that would function as a Red Army advisory body. Lenin and the Bolshevik Central Committee agreed to create a Supreme Military Council on 4 March, appointing Mikhail Bonch-Bruyevich, former chief of the imperial General Staff, as its head. At that point the entire Bolshevik leadership of the Red Army, including People's Commissar (defense minister) Nikolai Podvoisky and Krylenko, protested vigorously and eventually resigned. The office of the "Commander in Chief" was formally abolished by the Soviet government on 13 March, and Krylenko was reassigned to the Collegium of the Commissariat for Justice.

Legal career (1918–1934)

editFrom May 1918 and until 1922, Krylenko was Chairman of the Revolutionary Tribunal of the All-Russian Central Executive Committee. He simultaneously served as a member of the Collegium of Prosecutors of the Revolutionary Tribunal.

In May 1918, Leon Trotsky ordered that Soviet Navy Admiral Alexei Shchastny be put on trial for having refused to scuttle the Baltic Fleet. After a trial prosecuted by Krylenko, the presiding judge, Karklin, sentenced the Admiral, "To be shot within twenty four hours." Attendees reacted with dismay as Lenin had abolished the death penalty on 28 October 1917. Krylenko said to those present, "What are you worrying about? Executions have been abolished. But Shchastny is not being executed; he is being shot." The sentence was carried out soon after.[5][unreliable source?]

Krylenko was an enthusiastic proponent of the Red Terror, whatever his differences with the Cheka (the Soviet secret police), exclaiming, "We must execute not only the guilty. Execution of the innocent will impress the masses even more."[6]

In early 1919, Krylenko was involved in a dispute with the Cheka and was instrumental in taking away its right to execute people without a trial.[3] In 1922, Krylenko became Deputy Commissar of Justice and assistant Prosecutor General of the RSFSR, in which capacity he served as the chief prosecutor at the Moscow show trials of the 1920s.

Cieplak Trial

editIn early 1923, Krylenko acted as public prosecutor in the Moscow show trial of the Soviet Union's Roman Catholic hierarchy. The defendants included Archbishop Jan Cieplak, Monsignor Konstanty Budkiewicz, and Blessed Leonid Feodorov, the Exarch of the Russian Greek Catholic Church.

According to Father Christopher Lawrence Zugger,

"The Bolsheviks had already orchestrated several 'show trials.' The Cheka had staged the 'Trial of the St. Petersburg Combat Organization'; its successor, the new GPU, the 'Trial of the Socialist Revolutionaries.' In these and other such farces, defendants were inevitably sentenced to death or to long prison terms in the north. The Cieplak show trial is a prime example of Bolshevik revolutionary justice at this time. Normal judicial procedures did not restrict revolutionary tribunals at all; in fact, the prosecutor N.V. Krylenko, stated that the courts could trample upon the rights of classes other than the proletariat. Appeals from the courts went not to a higher court, but to political committees. Western observers found the setting – the grand ballroom of a former Noblemen's Club, with painted cherubs on the ceiling – singularly inappropriate for such a solemn event. Neither judges nor prosecutors were required to have a legal background, only a proper 'revolutionary' one. That the prominent 'No Smoking' signs were ignored by the judges themselves did not bode well for legalities."[7]

According to New York Herald correspondent Francis MacCullagh:

Krylenko, who began to speak at 6:10 PM, was moderate enough at first, but quickly launched into an attack on religion in general and the Catholic Church in particular. "The Catholic Church", he declared, "has always exploited the working classes." When he demanded the Archbishop's death, he said, "All the Jesuitical duplicity with which you have defended yourself will not save you from the death penalty. No Pope in the Vatican can save you now." As the long oration proceeded, the Red Procurator worked himself into a fury of anti-religious hatred. "Your religion", he yelled, "I spit on it, as I do on all religions, – on Orthodox, Jewish, Mohammedan, and the rest." "There is no law here but Soviet Law," he yelled at another stage, "and by that law you must die."[8]

Archbishop Cieplak and Monsignor Budkiewicz were both sentenced to death. The other fifteen defendants were sentenced to long terms in Solovki prison camp. The sentences touched off a massive uproar throughout the Western world.

According to Father Zugger,

"The Vatican, Germany, Poland, Great Britain, and the United States undertook frantic efforts to save the Archbishop and his chancellor. In Moscow, the ministers from the Polish, British, Czechoslovak, and Italian missions appealed 'on the grounds of humanity,' and Poland offered to exchange any prisoner to save the archbishop and the monsignor. Finally, on March 29, the Archbishop's sentence was commuted to ten years in prison, ... but the Monsignor was not to be spared. Again, there were appeals from foreign powers, from Western Socialists and Church leaders alike. These appeals were for naught: Pravda editorialized on March 30 that the tribunal was defending the rights of the workers, who had been oppressed by the bourgeois system for centuries with the aid of priests. Pro-Communist foreigners who intervened for the two men were also condemned as 'compromisers with the priestly servants of the bourgeoisie.' ...Father Rutkowski recorded later that Budkiewicz surrendered himself over to the will of God without reservation. On Easter Sunday, the world was told that the Monsignor was still alive, and Pope Pius XI publicly prayed at St. Peter's that the Soviets would spare his life. Moscow officials told foreign ministers and reporters that the Monsignor's sentence was just, and that the Soviet Union was a sovereign nation that would accept no interference. In reply to an appeal from the rabbis of New York City to spare Budkiewicz's life, Pravda wrote a blistering editorial against 'Jewish bankers who rule the world' and bluntly warned that the Soviets would kill Jewish opponents of the Revolution as well. Only on April 4 did the truth finally emerge: the Monsignor had already been in the grave for three days. When the news came to Rome, Pope Pius fell to his knees and wept as he prayed for the priest's soul. To make matters worse, Cardinal Gasparri had just finished reading a note from the Soviets saying that 'everything was proceeding satisfactorily' when he was handed the telegram announcing the execution. On March 31, 1923, Holy Saturday, at 11:30 PM, after a week of fervent prayers and a firm declaration that he was ready to be sacrificed for his sins, Monsignor Constantine Budkiewicz had been taken from his cell and, sometime before the dawn of Easter Sunday, shot in the back of the head on the steps of the Lubyanka prison.[9]

Later career

editKrylenko was appointed State Prosecutor in 1928, and acted as prosecutor in the first three show trials staged after Joseph Stalin had taken control of the communist party. At the Shakhty Trial, in 1928, Krylenko called for death sentences for all 52 defendants. He was also the prosecutor at the Industrial Party Trial in 1930, and the Menshevik Trial in 1931, at which he called for death sentences for five of the 14 defendants.

In 1931 Krylenko became Commissar of Justice. He stepped down as Prosecutor General in 1932 and was replaced by Andrei Vyshinsky. In 1933, Krylenko was awarded the Order of Lenin.[10]

In January 1933, he waxed indignant about the leniency of some Soviet officials who objected to the infamous "five ears law":

We are sometimes up against a flat refusal to apply this law rigidly. One People's Judge told me flatly that he could never bring himself to throw someone in jail for stealing four ears. What we're up against here is a deep prejudice, imbibed with their mother's milk... a mistaken belief that people should be tried in accordance not with the Party's political guidelines but with considerations of "higher justice".[11]

From 1927 to 1934, Krylenko was a member of the Central Control Commission of the Communist Party.

Sport positions

editIn the 1930s, Krylenko headed the Soviet chess, checkers and mountain climbing associations. He was one of the pioneers of the Pamirs mountain climbing, leading the Soviet half of a joint Soviet–German expedition in 1928 as well as expeditions to the Eastern Pamirs in 1931 and to the Lenin Peak in 1934.[4] Krylenko used his positions to carry out the Stalinist line of total control and politicization of all areas of public life:

We must finish once and for all with the neutrality of chess. We must condemn once and for all the formula "chess for the sake of chess", like the formula "art for art's sake". We must organize shockbrigades of chess-players, and begin immediate realization of a Five-Year Plan for chess.[5]

It should also be noted that Krylenko himself was a strong club-level chess player.

According to British grandmaster Daniel King, Krylenko's work promoting chess was an extension of his role in the Soviet anti-religious campaigns; "The Bolsheviks' motives for promoting Chess were both ideological and political. They hoped that this logical and rational game might wean the masses away from belief in the Russian Orthodox Church; but they also wanted to prove the intellectual superiority of the Soviet people over the capitalist nations. Put simply, it was part of world domination.

"With chess,... they hit upon a winner: equipment was cheap to produce; tournaments relatively easy to organise; and they were already building on an existing tradition. Soon there were chess clubs in factories, on farms, in the army... This vast social experiment quickly bore fruit."[12]

In 1935, Krylenko invited the former chess world champion Emanuel Lasker to Soviet Union, where he settled until 1937.

Theorist of the Soviet Justice System

editAccording to his brother in law Max Eastman, Krylenko was "gentle-hearted and poetic in his youth" but "hardened up under Lenin's influence" to become "a ruthless Bolshevik".[13][unreliable source?] Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, he wrote dozens of books and articles in support of his philosophy of "socialist legality."

According to Krylenko, political considerations rather than evidence needed to play the decisive role in deciding the verdict and sentence before trial. He further argued that even a confession obtained under torture constituted proof of a defendant's guilt; material evidence, precise definitions of a crime, or judicial sentencing guidelines were not needed under socialism.

Mikhail Yakubovich, a defendant in one of the show trials, described meeting with Krylenko after weeks of torture by the OGPU to discuss his upcoming trial:

Offering me a seat, Krylenko said: "I have no doubt that you personally are not guilty of anything. We are both performing our duty to the Party—I have considered and consider you a Communist. I will be the prosecutor at the trial; you will confirm the testimony given during the investigation. This is our duty to the Party, yours and mine. Unforeseen complications may arise at the trial. I will count on you. If the need should arise, I will ask the presiding judge to call on you. And you will find the right words."[14]

Krylenko promoted his views on socialist legality during the work on two drafts of the Soviet Penal Code, one in 1930 and one in 1934. Krylenko's views were opposed by some Soviet theoreticians, including Soviet Prosecutor General Andrey Vyshinsky. According to Vyshinsky, Krylenko's imprecise definition of crimes and his refusal to define terms of punishment introduced legal instability and arbitrariness and were, therefore, against the interests of the Party. Their debates continued throughout 1935 and were inconclusive.

With the start of the Great Purge after Sergei Kirov's assassination on 1 December 1934, Krylenko's star began to fade and Stalin began to increasingly favor Vyshinsky. Notably, it was Vyshinsky and not Krylenko who prosecuted the first two high-profile Moscow show trials of Old Bolsheviks in August 1936 and January 1937. Krylenko's ally, the Marxist theoretician Eugen Pashukanis, was subjected to severe criticism in late 1936 and arrested in January 1937 and shot in September. Soon after Pashukanis's arrest, Krylenko was forced to publicly "admit his mistakes" and concede that Vyshinsky and his allies had been right all along. [6]

In 1936, Krylenko justified the inclusion of a law against male homosexuality in the 1934 Soviet penal code as a measure directed against subversive activities:

So who are the bulk of our clients in these sorts of cases? Is it the working class? No! It's classless hoodlums. Classless hoodlums, either from the dregs of the society, or from the remains of the exploiters' class. They have no place to go. So they take to – pederasty. Together with them, next to them, under this excuse, in stinky secretive bordellos another kind of activity takes place as well – counter-revolutionary work.[7]

Fall from power and execution

editKrylenko was promoted to Commissar of Justice of the USSR[15] on 20 July 1936, and was directly involved in the first waves of Joseph Stalin's Great Purges between 1935 and 1938. However, at the first session of the newly reorganized Supreme Soviet of the Soviet Union in January 1938, he was denounced by an up-and-coming Stalinist, Mir Jafar Baghirov:

Comrade Krylenko concerns himself only incidentally with the affairs of his commissariat. But to direct the Commissariat of Justice, great initiative and a serious attitude toward oneself is required. Whereas Comrade Krylenko used to spend a great deal of time on mountain-climbing and traveling, now he devotes a great deal of time to playing chess... We need to know what we are dealing with in the case of Comrade Krylenko—the commissar of justice? or a mountain climber? I don't know which Comrade Krylenko thinks of himself as, but he is without doubt a poor people's commissar.[8]

The attack had been carefully prepared in advance and Molotov endorsed it. In response, Stalin removed Krylenko from his post on 19 January 1938, turning the Commissariat over to his replacement, N. M. Rychkov. Leaving the Kremlin, Krylenko and his family traveled to his dacha outside Moscow. On the evening of 31 January 1938, Krylenko received a phone call from Stalin, who told him, saying: "Don't get upset. We trust you. Keep doing the work you were assigned to on the new legal code." This phone call calmed Krylenko, but later that evening his home was raided by an NKVD squad. Krylenko and his family were arrested.[14]

After three days of interrogation and torture by the NKVD, Krylenko "confessed" that he had been a "wrecker" since 1930. On April 3, he made an additional statement, claiming to have been an enemy of Lenin before the October Revolution. During his last interrogation on 28 June 1938, Krylenko named thirty Commissariat of Justice officials whom he had allegedly recruited into an anti-Soviet conspiracy, including Vladimir Antonov-Ovseyenko.[16]

Nikolai Krylenko was tried by the Military Collegium of the Soviet Supreme Court on 29 July 1938. In accordance with Krylenko's own theories of socialist legality, the verdict and sentence had been decided in advance. The trial lasted only twenty minutes, just long enough for Krylenko to retract his false confessions.[17] After being found guilty, he was taken away and immediately shot once in the back of the head.

Personality

editThe writer Razumnik Ivanov-Razumnik was in prison with Krylenko in 1938, and described him as "notorious and universally disliked".[18] This seems to have a common view. The British agent Robert Bruce Lockhart described him as "an epileptic degenerate" and "the most repulsive type".[19] Covering the Industrial Party trial, the American journalist Eugene Lyons was struck by how "Prosecutor Krylenko's bullet-head shone in the arc-lights, his flat Scythian features tensed in his cruel sneer."[20] Another journalist, William Reswick, watched Krylenko summing up for the prosecution at the Shakhty Trial:

With but an hour’s interruption for lunch, the obviously psychopathic prosecutor raved from ten in the morning until sunset. It was a stump speech delivered by a bald-headed little man with feverish grey eyes blazing with anger. Towards the end of his ten-hour harangue, the prosecutor was actually foaming at the mouth. After a day of screaming platitudes, Krylenko … was too exhausted to speak with coherence. He had reached a state of frenzy where he spat words of venom, hurling them at his victims in a fit of raving madness. As if carried away by a lust for murder, he demanded death for every defendant.[21]

Legacy

editThe NKVD officer who had taken Krylenko's testimony, one Kogan, probably Captain Lazar V. Kogan, who also interrogated Nicolai Bukharin[22] and Genrikh Yagoda,[23] was, in turn, shot in 1939 (probably, on March 2[24]) for "anti-Soviet activity".[9] Krylenko's conviction was one of the first annulled by the Soviet State in 1955, during the Khrushchev thaw.

Krylenko's ex-wife and fellow Old Bolshevik Elena Rozmirovich survived the purges by keeping a low profile and working in the Party archives.[10]

His sister Elena Krylenko worked for Maxim Litvinov in the Ministry for Foreign Affairs (although she was never a member of the Party); in 1924 she decided to leave Russia with the American writer Max Eastman (who had been in Russia for almost two years, researching and writing a life of Trotsky). To enable her to leave, Litvinov agreed to pass her off as a member of his delegation when he travelled to London for an international conference. But she could not leave the delegation and remain in a free country without a passport, which the Bolsheviks would not give her. So, in the hours before their train left, she and Max Eastman got married. They were still married and living in America when she died in 1956. Thus she escaped the purges.[25][11]

Furthermore, Krylenko's creation of what was later dubbed "The Soviet Chess Machine" led Soviet Grandmasters to dominate the World Chess Championship for most of the remainder of the 20th century, producing a string of World Chess Champions including Mikhail Botvinnik, Vasily Smyslov, Mikhail Tal, Tigran Petrosian, Boris Spassky, Anatoly Karpov, and Garry Kasparov.

Notes

edit- ^ See Arthur Ransome. In 1919, Kessinger Publishing, 2004, ISBN 978-1-4191-6717-1 p. 49

- ^ See Israel Getzler. Martov: A Political Biography of a Russian Social Democrat, Cambridge University Press, 2003, ISBN 978-0-521-52602-9 p. 177

- ^ See Arthur Ransome, op. cit, p. 46

- ^ See Audrey Salkeld. On the Edge of Europe: Mountaineering in the Caucasus, London, Hodder and Stoughton, 1993, ISBN 978-0-89886-388-8 p. 164

- ^ Quoted in Robert Conquest. The Great Terror: A Reassessment, Oxford University Press, 1990, ISBN 978-0-19-507132-0 p. 249

- ^ See David Tuller. Cracks in the Iron Closet: Travels in Gay and Lesbian Russia, University of Chicago Press, 1996, ISBN 978-0-226-81568-8 p. 6

- ^ See Hiroshi Oda. "Criminal Law Reform in the Soviet Union under Stalin", in The Distinctiveness of Soviet Law, Dordrecht, the Netherlands, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, 1987, ISBN 978-90-247-3576-1 p. 90–92

- ^ Quoted from the official protocols published in 1938 by Roy A. Medvedev in "New Pages from the Political Biography of Stalin" published in Stalinism: Essays in Historical Interpretation, edited by Robert C. Tucker, originally published by W.W. Norton and Co in 1977, revised edition published by Transaction Publishers (New Brunswick, New Jersey) in 1999, ISBN 978-0-7658-0483-9 p. 217

- ^ See Donald D. Barry and Yuri Feofanov. Politics and Justice in Russia: Major Trials of the Post-Stalin Era, New York, M. E. Sharpe, 1996, ISBN 978-1-56324-344-8, p. 233.

- ^ See Barbara Evans Clements. Bolshevik Women, Cambridge University Press, 1997, ISBN 978-0-521-59920-7 p. 287.

- ^ See, e.g., Richard Kennedy. Dreams in the Mirror: A Biography of E. E. Cummings, New York, W. W. Norton and Co., 1980, ISBN 978-0-87140-155-7 (2nd, 1994 edition) p. 382

Resources

edit- ^ Max Eastman, Love and Revolution: My Journey through an Epoch (New York: Random House, 1964.pp.338–9

- ^ An eye-witness, Captain George Hill, described it in his memoir, Go Spy the Land (London: Cassell, 1932), p.110

- ^ A Soviet Heretic: The Essays of Yevgeny Zamyatin. trans. Mirra Ginsberg (London: Quartet Books, 1970). p. 22.

- ^ A Soviet Heretic: The Essays of Yevgeny Zamyatin. trans. Mirra Ginsberg (London: Quartet Books, (1970). p. 25.

- ^ Alexander Solzhenitsyn, The Gulag Archipelago: An Experiment in Literary Investigation, Volume I, pp. 434–435.

- ^ Richard Pipes, The Russian Revolution; p. 822

- ^ Father Christopher Lawrence Zugger, The Forgotten: Catholics in the Soviet Empire from Lenin through Stalin, Syracuse University Press, 2001; p. 182

- ^ Captain Francis McCullagh, The Bolshevik Persecution of Christianity, E.P. Dutton and Company, 1924. Page 221.

- ^ Father Christopher Lawrence Zugger, The Forgotten: Catholics in the Soviet Empire from Lenin through Stalin, Syracuse University Press, 2001; pp. 187–188

- ^ "Krylenko & Carfare". Time. 6 February 1933. Archived from the original on 22 November 2010. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- ^ Edvard Radzinsky, Stalin: The First In-Depth Biography Based on Explosive New Documents from Russia's Secret Archives (1997), p. 258.

- ^ David Shenk (2006), The Immortal Game: A History of Chess, page 169.

- ^ Eastman, p.342

- ^ a b Medvedev, Roy; George Shriver (1990). Let History Judge: The Origins and Consequences of Stalinism. Columbia University Press. p. 891 pages. ISBN 978-0-231-06351-7.

- ^ the whole Soviet Union as opposed to just the Russian Federation

- ^ "Записка Р.А. Руденко в ЦК КПСС о реабилитации Н.В. Крыленко. 11 мая 1955 г. (Note by R.A.Rudenko to the Central Committee of the CPSU on the rehabilitation of N.V.Krylenko)". Реабилитация: как ето было, документы президиума ЦК КПСС и другие материалы, март 1953 – февраль 1956. Международный фонд "демократияя" (Moscow). Retrieved 22 January 2023.

- ^ Arbitrary Justice: Courts and Politics in Post Stalin Russia

- ^ Ivanov-Razumnik, Razumnik (1965). The Memoirs of Ivanov-Razumnik. London: Oxford U.P. p. 313.

- ^ Bruce Lockhart, R.H. (1932). Memoirs of a British Agent. London: Putnam. p. 257.

- ^ Lyons, Eugene (n.d.). Assignment in Utopia. London: George Harrap & Co. p. 372.

- ^ Reswick, William (1952). I Dreamt Revolution. Chicago: Henry Regnary. p. 249. Retrieved 1 April 2021.

- ^ Nikolai Bukharin, George Shriver, Stephen F. Cohen, How It All Began, p. XVIII

- ^ Nikita Petrov and Marc Jansen, Stalin’s Loyal Executioner: People’s Commissar Nikolai Ezhov 1895–1940, 04 April 2002, ISBN 978-0-8179-2902-2, page 62 (chapter 3), available online at: [1] Archived 2010-11-26 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Michael Parrish, Sacrifice of the Generals: Soviet Senior Officer Losses, 1939–1953, p. xxii

- ^ Eastman, pp.435–6

Works (in English)

edit- N. V. Krylenko. A blow at Intervention. Final indictment in the case of the counter-revolutionary Organisation of the Union of Engineers’ Organisations (the Industrial Party) whereby Ramzin, Kalinnikof, Larichef, Charnowsky, Fedotof, Kupriyánof, Ochkin and Sitnin, the accused, are charged in accordance with article 58, paragraphs 3, 4, and 6 of the Criminal code of the RSFSR. Pref. by Karl Radek. Moscow, State Publishers, 1931.

- N. V. Krylenko. Red and white terror, London, Communist Party of Great Britain, 1928.

- N. V. Krylenko. Revolutionary law. Moscow, Co-operative Publishing Society of Foreign Workers in the U.S.S.R., 1933.

References

edit- Leoncini, Mario (2008). Scaccopoli. Le mani della politica sugli scacchi. Florence: Phasar. ISBN 978-88-87911-97-8.

- Anatolii Pavlovich Shikman (А.П. Шикман). Important Figures of Russian History: A Biographical Dictionary (Деятели отечественной истории. Биографический справочник.) in 2 volumes. Moscow, AST, 1997, ISBN 978-5-15-000087-2 (vol 1) ISBN 978-5-15-000089-6 (vol 2)

- Konstantin Aleksandrovich Zalesskii (К.А. Залесский). Stalin's Empire: A Biographical Encyclopedic Dictionary. (Империя Сталина. Биографический энциклопедический словарь.) Moscow, Veche, 2000, ISBN 978-5-7838-0716-9

- Pavel Vasil'evich Volobuev, ed. (1993). "Russian Politicians, 1917: A Biographical Dictionary (Политические деятели России 1917. Биографический словарь". Bol'shaia Rossiiskaia Entsiklopediia. Moscow. ISBN 978-5-85270-137-4.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)