On 1 June 1642[1] the English Lords and Commons approved a list of proposals known as the Nineteen Propositions, sent to King Charles I of England, who was in York at the time.[2] In these demands, the Long Parliament sought a larger share of power in the governance of the kingdom. Among the MPs' proposals was Parliamentary supervision of foreign policy and responsibility for the command of the militia, the non-professional body of the army, as well as making the King's ministers accountable to Parliament.[3][4] Before the end of the month the King rejected the Propositions and in August the country descended into civil war.

Contents

editThe opening paragraph of the Nineteen Propositions introduces the document as a petition which it is hoped that Charles, in his "princely wisdom," will be "pleased to grant."[5] The nineteen numbered points may be summarised as follows:

| 1. Ministers serving on Charles' Privy Council must be approved by the House of Commons and the House of Lords. |

| 2. Matters that concern the public must be debated in Parliament, not decided based upon the advice of private advisors. |

| 3. That the Lord High Steward of England, Lord High Constable, Lord Chancellor, Lord Keeper of the Great Seal, Lord Treasurer, Lord Privy Seal, Earl Marshall, Lord Admiral, the Warden of the Cinque Ports, the Chief Governor of Ireland, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, Master of the Wards, the Secretaries of State, the two Chief Justices and Chief Baron, may always be chosen with the approbation of both Houses of Parliament; and in the intervals of Parliament, by assent of the major part of the Council, in such manner as is before expressed in the choice of councillor |

| 4. The education of the King's children is subject to Parliamentary approval. |

| 5. The King's children may not marry anyone without the consent of Parliament. |

| 6. Laws against Jesuits, Catholic priests, and Catholic recusants must be strictly enforced. |

| 7. The vote of Catholic Lords shall be taken away, and the children of Catholics must receive a Protestant education. |

| 8. A reformation of the Church government must be made. |

| 9. Charles will accept the ordering of the militia by the Lords and Commons. |

| 10. Members of Parliament who have been put out of office during the present session must be allowed to return. |

| 11. Councilors and judges must take an oath to maintain certain Parliamentary statutes. |

| 12. All judges and officers approved of by Parliament shall hold their posts on condition of good behavior. |

| 13. The justice of Parliament shall apply to all law-breakers, whether they are inside the country or have fled. |

| 14. Charles's pardon must be granted, unless both houses of Parliament object. |

| 15. Parliament must approve Charles' appointees for commanders of the forts and castles of the kingdom. |

| 16. The unnecessary military attachment guarding Charles must be discharged. |

| 17. The Kingdom will formalize its alliance with the Protestant states of the United Provinces (the Dutch) in order to defend them against the Pope and his followers. |

| 18. Charles must clear the five members of the House of Commons, along with Lord Kimbolton, of any wrongdoing. |

| 19. New peers of the House of Lords must be voted in by both Houses of Parliament.[5] |

It concluded "And these our humble desires being granted by your Majesty, we shall forthwith apply ourselves to regulate your present revenue in such sort as may be for your best advantage; and likewise to settle such an ordinary and constant increase of it, as shall be sufficient to support your royal dignity in honour and plenty, beyond the proportion of any former grants of the subjects of this kingdom to your Majesty's royal predecessors."[6]

King's response

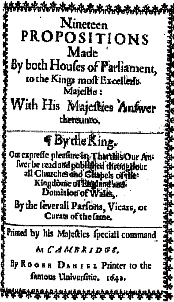

editThe King's response was lengthy and entirely negative. He stated "For all these reasons to all these demands our answer is, Nolumus Leges Angliae mutari [We are unwilling to change the laws of England]."[7] On 21 June 1642[8] the King's answer was read in Parliament, and it was ordered that it be displayed in the churches of England and Wales. At least six editions were also published.[9]

Aftermath

editWhen examined in the context of longstanding tense relations between British monarchy and Parliament, The Nineteen Propositions can be seen as the turning point between attempted conciliation between the King and Parliament and war.

In August 1642 the government split into two factions: the Cavaliers (Royalists) and the Roundheads (Parliamentarians), the latter of which would emerge victorious with Oliver Cromwell as its leader. The idea of mixed government and the three Estates, popularized by Charles's Answer to the Nineteen Propositions, remained dominant until the 19th century.[9]

References

edit- ^ The Parliamentary or Constitutional History of England, Vol. XI. London: William Sandry. 1753. pp. 129–135. Retrieved 28 August 2018.

- ^ Parliament approved the Propositions on June 1, but the text that was sent is dated June 3.

- ^ Plant, David The Nineteen Propositions

- ^ British Civil Wars & Commonwealth website Retrieved 3 March 2010

- ^ a b Text of the Nineteen Propositions (Wikisource) 53. The Nineteen Propositions sent by the two Houses of Parliament to the King at York

- ^ Sources and Debates in English History

- ^ "1642: Propositions made by Parliament and Charles I's Answer". Online Library of Liberty. Retrieved 26 November 2020.

- ^ The Parliamentary or Constitutional History of England, Vol. XI. London: William Sandry. 1753. pp. 233–242.

- ^ a b Weston, Corinne Comstock. "English Constitutional Doctrines from the Fifteenth Century to the Seventeenth: II. The Theory of Mixed Monarchy under Charles I and after" The English Historical Review, Vol. 75, No. 296 (Jul., 1960), pp. 42