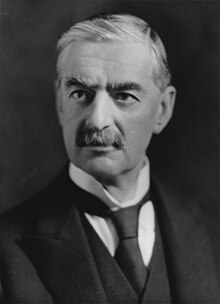

The Norway Debate, sometimes called the Narvik Debate, was a momentous debate in the British House of Commons from 7 to 9 May 1940, during the Second World War. The official title of the debate, as held in the Hansard parliamentary archive, is Conduct of the War. The debate was initiated by an adjournment motion enabling the Commons to freely discuss the progress of the Norwegian campaign. The debate quickly brought to a head widespread dissatisfaction with the conduct of the war by Neville Chamberlain's government.

At the end of the second day, there was a division of the House for the members to hold a no confidence motion.[a] The vote was won by the government but by a drastically reduced majority. That led on 10 May to Chamberlain resigning as prime minister and the replacement of his war ministry by a broadly based coalition government, which, under Winston Churchill, governed the United Kingdom until after the end of the war in Europe in May 1945.

Chamberlain's government was criticised not only by the Opposition but also by respected members of his own Conservative Party. The Opposition forced the vote of no confidence, in which over a quarter of Conservative members voted with the Opposition or abstained, despite a three-line whip. There were calls for national unity to be established by formation of an all-party coalition but it was not possible for Chamberlain to reach agreement with the opposition Labour and Liberal parties. They refused to serve under him, although they were willing to accept another Conservative as prime minister. After Chamberlain resigned as prime minister (he remained Conservative Party leader until October 1940), they agreed to serve under Churchill.

Background

editIn 1937, Neville Chamberlain, then Chancellor of the Exchequer, succeeded Stanley Baldwin as prime minister, leading a National Government overwhelmingly composed of Conservatives but supported by small National Labour and Liberal National parties. It was opposed by the Labour and Liberal parties. Since assuming power in Germany in 1933, the Nazi Party had pushed an irredentist foreign policy. Chamberlain initially attempted to avert war by a policy of appeasement, such as the Munich Agreement, but this was abandoned after Germany abandoned diplomatic means and became more overtly expansionist with the occupation of Czechoslovakia in March 1939.

One of the strongest critics of both appeasement and German aggression was Conservative backbencher Winston Churchill who, although he was one of the country's most prominent political figures, had last held government office in 1929. After Germany invaded Poland on 1 September 1939, the United Kingdom and France declared war on Germany two days later. Chamberlain thereupon created a war cabinet into which he invited Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty. It was at this point that a government supporter (possibly David Margesson, the Government Chief Whip) noted privately:[1][b]

For two-and-a-half years, Neville Chamberlain has been Prime Minister of Great Britain. During this period Great Britain has suffered a series of diplomatic defeats and humiliations, culminating in the outbreak of European war. It is an unbroken record of failure in foreign policy, and there has been no outstanding success at home to offset the lack of it abroad. ... Yet it is probable that Neville Chamberlain still retains the confidence of the majority of his fellow country-men and that, if it were possible to obtain an accurate test of the feelings of the electorate, Chamberlain would be found the most popular statesman in the land.

Once Germany had rapidly overrun Poland in September 1939, there was a sustained period of military inactivity for over six months dubbed the "Phoney War". On 3 April 1940, Chamberlain said in an address to the Conservative National Union that Adolf Hitler, the German dictator, "had missed the bus".[2] Only six days later, on 9 April, Germany launched an attack in overwhelming force on neutral and unprepared Norway after swiftly occupying Denmark. In response, Britain deployed military forces to assist the Norwegians.

Churchill, as First Lord of the Admiralty, had direct responsibility for the conduct of naval operations in the Norwegian campaign. Before the German invasion, he had pressed the Cabinet to ignore Norway's neutrality, mine its territorial waters and be prepared to seize Narvik, in both cases to disrupt the export of Swedish iron ore to Germany during winter months, when the Baltic Sea was frozen. He had, however, advised that a major landing in Norway was not realistically within Germany's powers.[3] Apart from the naval victory in the Battles of Narvik, the Norwegian campaign went badly for the British forces, generally because of poor planning and organisation but essentially because military supplies were inadequate and, from 27 April, the Anglo-French forces were obliged to evacuate.[4]

When the House of Commons met on Thursday, 2 May, Labour leader Clement Attlee asked: "Is the Prime Minister now able to make a statement on the position in Norway?" Chamberlain was reluctant to discuss the military situation because of the security factors involved but did express a hope that he and Churchill would be able to say much more next week. He went on to make an interim statement of affairs but was not forthcoming about "certain operations (that) are in progress (as) we must do nothing which might jeopardise the lives of those engaged in them". He asked the House to defer comment and question until next week. Attlee agreed and so did Liberal leader Archibald Sinclair, except that he requested a debate on Norway lasting more than a single day.[5]

Attlee then presented Chamberlain with a private notice in which he requested a schedule for next week's Commons business. Chamberlain announced that a debate on the general conduct of the war would commence on Tuesday, 7 May.[6] The debate was keenly anticipated in both Parliament and the country. In his diary entry for Monday, 6 May, Chamberlain's Assistant Private Secretary John Colville wrote that all interest centred on the debate. Obviously, he thought, the government would win through but after facing some very awkward points about Norway. Some of Colville's colleagues including Lord Dunglass, who was Chamberlain's Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) at the time, considered the government position to be sound politically, but less so in other respects. Colville worried that "the confidence of the country may be somewhat shaken".[7]

7 May: first day of the debate

editPreamble and other business

editThe Commons sitting on Tuesday, 7 May 1940, began at 14:45 with Speaker Edward FitzRoy in the Chair.[8] There followed some private business matters and numerous oral answers to questions raised, many of those being about the British Army.[9]

With these matters completed, the debate on the Norwegian campaign began with a routine adjournment motion (i.e., "that this house do now adjourn"). Under Westminster rules in debates like this, wide-ranging discussions of a variety of topics are allowed, and the motion is not usually put to a vote.

At 15:48, Captain David Margesson, the Government Chief Whip, made the adjournment motion. The House proceeded to openly discuss "Conduct of the War", specifically the progress of the Norwegian campaign, and Chamberlain rose to make his opening statement.[10]

Chamberlain's opening speech

editChamberlain began by reminding the House of his statement on Thursday, 2 May, five days earlier, when it was known that British forces had been withdrawn from Åndalsnes. He was now able to confirm that they had also been withdrawn from Namsos to complete the evacuation of Allied forces from central and southern Norway (the campaign in northern Norway continued). Chamberlain attempted to treat the Allied losses as unimportant and claimed that British soldiers "man for man (were) superior to their foes". He praised the "splendid gallantry and dash" of the British forces but acknowledged they were "exposed ... to superior forces with superior equipment".[11]

Chamberlain then said he proposed "to present a picture of the situation" and to "consider certain criticisms of the government". He stated that "no doubt" the withdrawal had created a shock in both the House and the country. At this point, the interruptions began as a Labour member shouted: "All over the world".[11][12]

Chamberlain sarcastically responded that "ministers, of course, must be expected to be blamed for everything". This provoked a heated reaction with several members derisively shouting: "They missed the bus!"[13] The Speaker had to call on members not to interrupt, but they continued to repeat the phrase throughout Chamberlain's speech and he reacted with what has been described as "a rather feminine gesture of irritation".[14] He was eventually forced to defend the original usage of the phrase directly, claiming that he would have expected a German attack on the Allies at the outbreak of war when the difference in armed power was at its greatest.[15]

Chamberlain's speech has been widely criticised. Roy Jenkins called it "a tired, defensive speech which impressed nobody".[16] Liberal MP Henry Morris-Jones said Chamberlain looked "a shattered man" and spoke without his customary self-assurance.[14] When Chamberlain insisted that "the balance of advantage lay on our side", Liberal MP Dingle Foot could not believe what he was hearing and said Chamberlain was denying the fact that Britain had suffered a major defeat.[14] The backbench Conservative MP Leo Amery said Chamberlain's speech left the House in a restive and depressed, though not yet mutinous, state of mind. Amery believed that Chamberlain was "obviously satisfied with things as they stood" and, in the government camp, the mood was actually positive as they believed they were, in John Colville's words, "going to get away with it".[17]

Attlee's response to Chamberlain

editClement Attlee responded as Leader of the Opposition. He quoted some of Chamberlain's and Churchill's recent confident assertions about the likely victory of the British. Ministers' statements and, even more so, the press, guided (or deliberately left uncorrected) by the government, had painted far too optimistic a picture of the Norwegian campaign.[17] Given the level of confidence created, the setback had generated widespread disappointment. Attlee now raised the issue of government planning which would be revisited by several later speakers:[18]

It is said that in this war hitherto there has never been any initiative from our side, and it is said also that there is no real planning in anticipation of the possible strokes that will be taken against us. I think we must examine this affair from that aspect.

Chamberlain had announced additional powers being granted to Churchill which amounted to him having direction of the Chiefs of Staff. Attlee seized on this as an example of government incompetence, though without blaming Churchill, by saying:[19]

It is against all good rules of organisation that a man who is in charge of major strategy should also be in command of a particular unit. It is like having a man commanding an army in the field and also commanding a division. He has a divided interest between the wider questions of strategy and the problems affecting his own immediate command. The First Lord of the Admiralty has great abilities, but it is not fair to him that he should be put into an impossible position like that.

Attlee struck a theme here that would recur throughout the debate – that the government was incompetent but not Churchill himself, even though he was part of it, as he had suffered from what Jenkins calls a misdirection of his talents.[16] Jenkins remarks that Churchill's potential had not been fully utilised and, most importantly, he was clean of the stain of appeasement.[20]

Chamberlain had been heckled during his speech for having "missed the bus" and he made his case worse by desperately trying, and failing, to excuse his use of that expression a month earlier. In doing so, he provided Attlee with an opportunity. During the conclusion of his response, Attlee said:[21]

Norway follows Czechoslovakia and Poland. Everywhere the story is "too late". The Prime Minister talked about missing buses. What about all the buses which he and his associates have missed since 1931? They missed all the peace buses but caught the war bus.

Attlee's closing words were a direct attack on all Conservative members, blaming them for shoring up ministers whom they knew to be failures:[22]

They have allowed their loyalty to the Chief Whip to overcome their loyalty to the real needs of the country. I say that the House of Commons must take its full responsibility. I say that there is a widespread feeling in this country, not that we shall lose the war, that we will win the war, but that to win the war, we want different people at the helm from those who have led us into it.

Leo Amery said later that Attlee's restraint, in not calling for a division of the House (i.e., a vote), was of greater consequence than all his criticisms because, Amery believed, it made it much easier for Conservative members to be influenced by the debate's opening day.[23]

Sinclair's response to Chamberlain

editSir Archibald Sinclair, the leader of the Liberals, then spoke. He too was critical and began by comparing military and naval staff efficiency, which he considered proven, with political inefficiency:[24][c]

It is my contention that this breakdown in organisation occurred because there had been no foresight in the political direction of the war and in the instructions given to the Staffs to prepare for these very difficult operations in due time, and that the Staffs were hastily improvising instead of working to long and carefully-matured plans.

He drew from Chamberlain the admission that whilst troops had been held in readiness to be sent to Norway, no troopships had been retained to send them in. Sinclair gave instances of inadequate and defective equipment and of disorganisation reported to him by servicemen returning from Norway. Chamberlain had suggested that Allied plans had failed because the Norwegians had not put up the expected resistance to the Germans. Sinclair reported that the servicemen "paid a high tribute to the courage and determination with which the Norwegians fought alongside them. They paid a particular tribute to the Norwegian ski patrols. Norwegians at Lillehammer for seven days held up with rifles only a German force with tanks, armoured cars, bombing aeroplanes and all the paraphernalia of modern war".[24]

He concluded his speech by calling for Parliament to "speak out (and say) we must have done with half-measures (to promote) a policy for the more vigorous conduct of the war".[24]

No longer an ordinary debate

editThe rest of the first day's debate saw speeches both supporting and criticising the Chamberlain government. Sinclair was followed by two ex-soldiers, Brigadier Henry Page Croft for the Conservatives and Colonel Josiah Wedgwood for Labour. Derided by Labour,[25] Croft made an unconvincing case in support of Chamberlain and described the press as "the biggest dictator of all".[26]

Wedgwood denounced Croft for his "facile optimism, that saps the morale of the whole country".[27] Wedgwood warned of the dangers inherent in trying to negotiate with Hitler and urged prosecution of the war by "a government which can take this war seriously".[28][25]

Attending the debate was National Labour MP Harold Nicolson who was arguably the pre-eminent diarist of British politics in the twentieth century.[29] He took special notice of a comment made by Wedgwood which, in Nicolson's view, transformed "an ordinary debate (into) a tremendous conflict of wills".[25] Wedgwood had asked if the government was preparing any plan to prevent an invasion of Great Britain. A Conservative MP, Vice Admiral Ernest Taylor, interrupted and asked him if he had forgotten the Royal Navy. Wedgwood countered that with:[25][30]

The British Navy could perfectly well defend this country if it had not gone to the other end of the Mediterranean to keep itself safe from bombing.

Moments later, Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes, the Conservative Member for Portsmouth North, arrived in the chamber and caused a stir because he was resplendent in his uniform with gold braid and six rows of medal ribbons. He squeezed into a bench just behind Nicolson who passed him a piece of paper with Wedgwood's remark scribbled on it. Keyes went to the Speaker and asked to be called next as the honour of the navy was at stake, though he had really come to the House with the intention of criticising the Chamberlain government.[31]

Keyes: "I speak for the fighting Navy"

editWhen Wedgwood sat down, the Speaker called Keyes, who began by denouncing Wedgwood's comment as "a damned insult".[32] The House, especially David Lloyd George, "roared its applause".[32] Keyes quickly moved on and became the debate's first Tory rebel. As Jenkins puts it, Keyes "turned his guns on Chamberlain" but with the proviso that he was longing to see "proper use made of Churchill's great abilities".[33]

Keyes was a hero of the First World War representing a naval town and an Admiral of the Fleet (though no longer on the active list). He spoke mostly on the conduct of naval operations, particularly the abortive operations to retake Trondheim. Keyes told the House:[34]

I came to the House of Commons to-day in uniform for the first time because I wish to speak for some officers and men of the fighting, sea-going Navy who are very unhappy. I want to make it perfectly clear that it is not their fault that the German warships and transports which forced their way into Norwegian ports by treachery were not followed in and destroyed as they were at Narvik. It is not the fault of those for whom I speak that the enemy have been left in undisputable possession of vulnerable ports and aerodromes for nearly a month, have been given time to pour in reinforcements by sea and air, to land tanks, heavy artillery and mechanised transport, and have been given time to develop the air offensive which has had such a devastating effect on the morale of Whitehall. If they had been more courageously and offensively employed they might have done much to prevent these unhappy happenings and much to influence unfriendly neutrals.

As the House listened in silence, Keyes finished by quoting Horatio Nelson:[35]

There are hundreds of young officers who are waiting eagerly to seize Warburton-Lee's torch, or emulate the deeds of Vian of the "Cossack". One hundred and forty years ago, Nelson said, "I am of the opinion that the boldest measures are the safest" and that still holds good to-day.

It was 19:30 when Keyes sat down to "thunderous applause". Nicolson wrote that Keyes' speech was the most dramatic he had ever heard,[36] and the debate from that point on was no longer an investigation of the Norwegian campaign but "a criticism of the government's whole war effort".[37]

Jones and Bellenger

editThe next two speakers were National Liberal Lewis Jones and Labour's Frederick Bellenger, who was still a serving army officer and was evacuated from France only a month later. Jones, who supported Chamberlain, was unimpressive and was afterwards accused of introducing party politics into the debate. There was a general exodus from the chamber as Jones was speaking.[37] Bellenger, who repeated much of Attlee's earlier message, called "in the public interest" for a government "of a different character and a different nature".[38]

Amery: "In the name of God, go!"

editWhen Bellenger sat down, it was 20:03 and the Deputy Speaker, Dennis Herbert, called on Leo Amery, who had been trying for several hours to gain the Speaker's attention. Amery later remarked that there were "barely a dozen" members present (Nicolson was among them) as he began to speak.[37] Nicolson, who expected a powerfully critical speech from Amery, wrote that the temperature continued to rise as Amery began and his speech soon "raised it far beyond the fever point".[39]

Amery had an ally in Clement Davies, chairman of the All Party Action Group which included some sixty MPs. Davies had been a National Liberal subject to the National Government whip but, in protest against Chamberlain, he had resigned it in December 1939 and crossed the floor of the House to rejoin the Liberals in opposition. Like many other members, Davies had gone to eat when Jones began speaking but, on hearing that Amery had been called, he rushed back to the chamber. Seeing that it was nearly empty, Davies approached Amery and urged him to deliver his full speech both to state his full case against the government and also to give Davies time to collect a large audience. Very soon, even though it was the dinner hour, the House began filling rapidly.[40]

Amery's speech is one of the most famous in parliamentary history.[40] As Davies had requested, he played for time until the chamber was nearly full. For much of the speech, the most notable absentee was Chamberlain himself, who was at Buckingham Palace for an audience with the King.[41] Amery began by criticising the government's planning and execution of the Norway campaign, especially their unpreparedness for it despite intelligence warning of likely German intervention and the clear possibility of some such response to the planned British infraction of Norwegian neutrality by the mining of Norwegian territorial waters. He gave an analogy from his own experience which illustrated the government's lack of initiative:[42]

I remember that many years ago in East Africa a young friend of mine went lion hunting. He secured a sleeping car on the railway and had it detached from the train at a siding near where he expected to find a certain man-eating lion. He went to rest and dream of hunting his lion in the morning. Unfortunately, the lion was out man-hunting that night. He clambered on to the rear of the car, scrabbled open the sliding door, and ate my friend. That is in brief the story of our initiative over Norway.

As tension increased in the House and Amery found himself speaking to a "crescendo of applause",[43] Edward Spears thought he was hurling huge stones at the government glasshouse with "the effect of a series of deafening explosions".[43] Amery widened his scope to criticise the government's whole conduct of the war to date. He moved towards his conclusion by calling for the formation of a "real" National Government in which the Trades Union Congress must be involved to "reinforce the strength of the national effort from inside".[44]

Although sources are somewhat divided on the point, there is a consensus among them that Chamberlain had arrived back in the chamber to hear Amery's conclusion. Nicolson recorded Chamberlain as sitting on a "glum and anxious front bench".[45] Amery said:[46]

Somehow or other we must get into the Government men who can match our enemies in fighting spirit, in daring, in resolution and in thirst for victory. Some 300 years ago, when this House found that its troops were being beaten again and again by the dash and daring of the Cavaliers, by Prince Rupert's Cavalry, Oliver Cromwell spoke to John Hampden. In one of his speeches he recounted what he said. It was this: I said to him, "Your troops are most of them old, decayed serving men and tapsters and such kind of fellows.... You must get men of a spirit that are likely to go as far as they[d] will go, or you will be beaten still". It may not be easy to find these men. They can be found only by trial and by ruthlessly discarding all who fail and have their failings discovered. We are fighting to-day for our life, for our liberty, for our all; we cannot go on being led as we are. I have quoted certain words of Oliver Cromwell. I will quote certain other words. I do it with great reluctance, because I am speaking of those who are old friends and associates of mine, but they are words which, I think, are applicable to the present situation. This is what Cromwell said to the Long Parliament when he thought it was no longer fit to conduct the affairs of the nation: "You have sat too long here for any good you have been doing. Depart, I say, and let us have done with you. In the name of God, go".

Amery delivered the last six words in a near whisper, pointing at Chamberlain as he did so. He sat down and the government's opponents cheered him.[45]

Afterwards, Lloyd George told Amery that his ending was the most dramatic climax he had heard to any speech. Amery himself said he thought he had helped push the Labour Party into forcing a division next day.[47] Harold Macmillan said later that Amery's speech "effectively destroyed the Chamberlain government".[48]

Later speeches

editIt was 20:44 when Amery sat down and the debate continued until 23:30. The next speech was by Sir Archibald Southby, who tried to defend Chamberlain.[49]

It is easy to talk glibly of Ministers' failure without specifying exactly in what way they have failed; it is easy to throw about charges of ineptitude, inability and procrastination without specifying exactly to what degree those charges are able to be substantiated. I listened to every word that the right hon. Gentleman said. He was full of general accusations of failure against the Government. It seemed to me that if he had been in charge of the affairs of the nation at the beginning of the war, rightly or wrongly, he would have considered that the proper action for us to have taken would have been to have gone into Norway and Sweden before Germany did. He may be right or wrong in that view. But if he was right in that view then we would, I presume, be doing right now to go into Holland and Belgium lest Germany should come in there before us.

He declared that Amery's speech would "certainly give great satisfaction in Berlin" and he was shouted down. Bob Boothby interrupted and said that "it will give greater satisfaction in this country".[50]

Southby was followed by Labour's James Milner who expressed the profound dissatisfaction with recent events of the majority of his constituents in Leeds. He called for "drastic change" to be made if Great Britain was to win the war.[51] Edward Turnour, 6th Earl Winterton spoke next, commencing at 21:28. Although a Conservative, he began by saying that there was a great deal in Milner's speech with which he was in agreement, but almost nothing in Southby's with which he could agree.[52]

The next speaker was Arthur Greenwood, the Labour deputy leader. He gave what Jenkins calls "a robust Labour wind-up".[47] In his conclusion, Greenwood called for "an active, vigorous, imaginative direction of the war" which had so far been lacking as the government was passive and on the defensive because "(as) the world must know, we have never taken the initiative in this war".[53] Summing up for the government was Oliver Stanley, the Secretary of State for War, whose reply to Greenwood has been described as ineffective.[47]

8 May: second day and division

editMorrison: "We must divide the House"

editIt is generally understood that Labour did not intend a division before the debate began but Attlee, after hearing the speeches by Keyes and Amery, realised that discontent within Tory ranks was far deeper than they had thought. A meeting of the party's Parliamentary Executive was held on Wednesday morning and Attlee proposed forcing a division at the end of the debate that day. There were a handful of dissenters, including Hugh Dalton, but they were outvoted at a second meeting later on.[54]

As a result, when Herbert Morrison reopened the debate just after 16:00, he announced that:[55]

In view of the gravity of the events which we are debating, that the House has a duty and that every Member has a responsibility to record his particular judgment upon them, we feel we must divide the House at the end of our Debate to-day.

Jenkins says the Labour decision to divide turned the routine adjournment motion into "the equivalent of a vote of censure".[47] Earlier in his opening address, Morrison had focused his criticism on Chamberlain, John Simon and Samuel Hoare who were the three ministers most readily associated with appeasement.[54]

Chamberlain: "I have friends in the House"

editHoare, the Secretary of State for Air, was scheduled to speak next but Chamberlain insisted on replying to Morrison and made an ill-judged and disastrous intervention.[56] Chamberlain appealed not for national unity but for the support of his friends in the House:[57]

The words which the right honourable Gentleman has just uttered make it necessary for me to intervene for a moment or two at this stage. The right honourable Gentleman began his speech by emphasising the gravity of the occasion. What he has said, the challenge which he has thrown out to the Government in general and the attack which he has made on them, and upon me in particular, make it graver still. Naturally, as head of the Government, I accept the primary responsibility for the actions of the Government, and my colleagues will not be slow to accept their responsibility too for the actions of the Government. But it is grave, not because of any personal consideration – because none of us would desire to hold on to office for a moment longer than we retained the confidence of this House – but because, as I warned the House yesterday, this is a time of national danger, and we are facing a relentless enemy who must be fought by the united action of this country. It may well be that it is a duty to criticise the Government. I do not seek to evade criticism, but I say this to my friends in the House – and I have friends in the House. No Government can prosecute a war efficiently unless it has public and Parliamentary support. I accept the challenge. I welcome it indeed. At least we shall see who is with us and who is against us, and I call on my friends to support us in the Lobby tonight.

That shocked many present who regarded it as divisive to be so explicit in relying on whipped support from his own party.[58] Bob Boothby, a Conservative MP who was a strong critic of Chamberlain, called out: "Not I"; and received a withering glare from Chamberlain.[59] The stress on "friends" was considered partisan and divisive, reducing politics at a time of crisis from national level to personal level.[47][59]

Hoare followed Chamberlain and struggled to cope with many of the questions being fired at him about the air force, at one point failing to realise the difference between the Royal Air Force and the Fleet Air Arm. He sat down at 17:37 and was succeeded by David Lloyd George.[60]

Lloyd George: "the worst strategic position in which this country has ever been placed"

editLloyd George had been prime minister during the last two years of the First World War. He was now 77, and it was to be his last major contribution to debate in the House in which he had sat for 50 years.[61] There was personal animosity between Lloyd George and Chamberlain.[47] The latter's appeal to friends gave Lloyd George the opportunity for retribution.[47] First, he attacked the conduct of the campaign and began by dismissing Hoare's entire speech in a single sentence:[62]

I have heard most of the speech of the right honourable Gentleman the Secretary of State for Air, and I should think that the facts which he gave us justify the criticism against the Government and are no defence of the Government.

Lloyd George then began his main attack on the government by focusing on the lack of planning and preparation:[62]

We did not take any measures that would guarantee success. This vital expedition, which would have made a vast difference to this country's strategical position, and an infinite difference to her prestige in the world, was made dependent upon this half-prepared, half-baked expeditionary force, without any combination at all between the Army and the Navy. There could not have been a more serious condemnation of the whole action of the Government in respect of Norway. ... The right honourable Gentleman spoke about the gallantry of our men, and we are all equally proud of them. It thrills us to read the stories. All the more shame that we should have made fools of them.

Emphasising the gravity of the situation, he argued that Britain was in the worst position strategically that it had ever been as a result of foreign policy failures, which he began to review from the 1938 Munich agreement onwards. Interrupted at this point, he retorted:[63]

You will have to listen to it, either now or later on. Hitler does not hold himself answerable to the whips or the Patronage Secretary.

Lloyd George went on to say that British prestige had been greatly impaired, especially in America. Before the events in Norway, he claimed, the Americans had been in no doubt that the Allies would win the war, but now they were saying it would be up to them to defend democracy. After dealing with some interruptions, Lloyd George criticised the rate of re-armament pre-war and to date:[64]

Is there anyone in this House who will say that he is satisfied with the speed and efficiency of the preparations in any respect for air, for Army, yea, for Navy? Everybody is disappointed. Everybody knows that whatever was done was done half-heartedly, ineffectively, without drive and unintelligently. For three or four years I thought to myself that the facts with regard to Germany were exaggerated by the First Lord, because the then Prime Minister – not this Prime Minister – said that they were not true. The First Lord was right about it. Then came the war. The tempo was hardly speeded up. There was the same leisureliness and inefficiency. Will anybody tell me that he is satisfied with what we have done about aeroplanes, tanks, guns, especially anti-aircraft guns? Is anyone here satisfied with the steps we took to train an Army to use them? Nobody is satisfied. The whole world knows that. And here we are in the worst strategic position in which this country has ever been placed.

Churchill and Chamberlain intervene in Lloyd George's speech

editDealing with an intervention at this point, Lloyd George said, in passing, that he did not think that the First Lord was entirely responsible for all the things that happened in Norway. Churchill intervened and said:[65]

I take complete responsibility for everything that has been done by the Admiralty, and I take my full share of the burden.

In answer, Lloyd George said:[66]

The right honourable Gentleman must not allow himself to be converted into an air-raid shelter to keep the splinters from hitting his colleagues.

Jenkins calls this "a brilliant metaphor" but wonders if it was spontaneous.[67] It produced laughter throughout the House, except on the government front bench where, with one exception, all the faces were stony. A spectator in the gallery, Baba Metcalfe, recorded that the exception was Churchill himself. She recalled him swinging his legs and trying hard not to laugh.[68] When things calmed down, Lloyd George resumed and now turned his fire onto Chamberlain personally:[66]

But that is the position, and we must face it. I agree with the Prime Minister that we must face it as a people and not as a party, nor as a personal issue. The Prime Minister is not in a position to make his personality in this respect inseparable from the interests of the country.

Chamberlain stood and, leaning over the despatch box,[69] demanded:[70]

What is the meaning of that observation? I have never represented that my personality [Hon. members: "You did!"] On the contrary, I took pains to say that personalities ought to have no place in these matters.

Lloyd George: Chamberlain "should sacrifice the seals of office"

editLloyd George responded to that intervention with a direct call for Chamberlain to resign:[66]

I was not here when the right honourable Gentleman made the observation, but he definitely appealed on a question which is a great national, imperial and world issue. He said, "I have got my friends". It is not a question of who are the Prime Minister's friends. It is a far bigger issue. The Prime Minister must remember that he has met this formidable foe of ours in peace and in war. He has always been worsted. He is not in a position to appeal on the ground of friendship. He has appealed for sacrifice. The nation is prepared for every sacrifice so long as it has leadership, so long as the Government show clearly what they are aiming at and so long as the nation is confident that those who are leading it are doing their best. I say solemnly that the Prime Minister should give an example of sacrifice, because there is nothing which can contribute more to victory in this war than that he should sacrifice the seals of office.

There was silence as Lloyd George sat down and one observer said that all the frustrations of the past eight months had been released. Chamberlain was deeply perturbed and, two days later, told a friend that he had never heard anything like it in Parliament. Churchill was overheard saying to Kingsley Wood that it was going to be "damned difficult" for him (Churchill) doing his summary later on.[71] Jenkins says the speech recalled Lloyd George in his prime. It was his best of many years, and his last of any real impact.[67]

Other speakers

editIt was 18:10 when Lloyd George concluded and some four hours later that Churchill began his summary to wind up the government's case ahead of the division. In the interim, several speakers were called to argue both for and against the government. They included long-serving Liberal National George Lambert, Sir Stafford Cripps, Alfred Duff Cooper, George Hicks, George Courthope, Robert Bower, Alfred Edwards, and Henry Brooke.[72] The last of these, Brooke, finished at 21:14 and gave way to A. V. Alexander who wound up for Labour and put forward certain questions that Churchill as First Lord might answer. His final point, however, was to criticise Chamberlain for his appeal to friendship:[73]

Since the Prime Minister made his intervention to-day, I have had more than one contact with representative neutrals in London, who feel that if this matter were to be judged upon the basis of putting personal friendship and personalities before the question of really winning the war, we should do a great deal to alienate the sympathy that remains with us in neutral spheres.

Jenkins describes Alexander as someone who tried, despite being completely different in character and personality, to make of himself a "mini-Churchill".[67] On this occasion, he did present Churchill with some awkward questions about Norway but, as with other speakers before him, it was done with genuine respect amidst severe criticism of Chamberlain, Hoare, Simon and Stanley in particular.[74] There was some embarrassment for Churchill in that he was late in returning to the House for Alexander's speech[75] and Chamberlain had to excuse his absence.[76] He arrived just in time for Alexander's questions about Norway.[75]

Churchill winds up for the Government

editChurchill was called to speak at 22:11, the first time in eleven years that he had wound up a debate on behalf of the government.[75] Many members believed that it was the most difficult speech of his career because he had to defend a reverse without damaging his own prestige.[77] It was widely felt that he achieved it because, as Nicolson described it, he said not one word against Chamberlain's government and yet, by means of his manner and his skill as an orator, he created the impression of being nothing to do with them.[74][77]

The first part of Churchill's speech was, as he said it would be, about the Norwegian campaign. The second part, concerning the vote of censure which he called a new issue that had been sprung upon the House at five o'clock, he said he would deal with in due course.[78]

Churchill proceeded to defend the conduct of the Norwegian campaign with some robustness, although there were several omissions such as his insistence that Narvik be blocked off with a minefield.[77] He explained that even the successful use of the battleship HMS Warspite at Narvik had put her at risk from many hazards. Had any come to pass, the operation, now hailed as an example of what should have been done elsewhere, would have been condemned as foolhardy:[79]

It is easy when you have no responsibility. If you dare, and forfeit is exacted, it is murder of our sailors; and if you are prudent, you are craven, cowardly, inept and timid.

As for the lack of action at Trondheim, Churchill said it was not because of any perceived danger, but because it was thought unnecessary. He reminded the House that the campaign continued in northern Norway, at Narvik in particular but he would not be drawn into giving any predictions about it. Instead, he attacked the government's critics by deploring what he called a cataract of unworthy suggestions and actual falsehoods during the last few days:[80]

A picture has been drawn of craven politicians hampering their admirals and generals in their bold designs. Others have suggested that I have personally overruled them, or that they themselves are inept and cowardly. Others again have suggested—for if truth is many-sided, mendacity is many-tongued—that I, personally, proposed to the Prime Minister and the War Cabinet more violent action and that they shrank from it and restrained it. There is not a word of truth in all that.

Churchill then had to deal with interruptions and an intervention by Arthur Greenwood who wanted to know if the war cabinet had delayed action at Trondheim. Churchill denied that and advised Greenwood to dismiss such delusions. Soon afterwards, he reacted to a comment by Labour MP Manny Shinwell:[81]

I dare say the honourable member does not like that. He skulks in the corner.

This produced a general uproar led by the veteran Scottish Labour member Neil Maclean, said to be the worse for drink, who demanded withdrawal of the word "skulks". The Speaker would not rule on the matter and Churchill defiantly refused to withdraw the comment, adding that:[82]

All day long we have had abuse, and now honourable members opposite will not even listen.

Having defended the conduct of the naval operations in the Norwegian campaign at some length, Churchill now said little about the proposed vote, other than to complain about such short notice:[82]

It seems to me that the House will be absolutely wrong to take such a grave decision in such a precipitate manner, and after such a little notice.

He concluded by saying:[83]

Let me say that I am not advocating controversy. We have stood it for the last two days, and if I have broken out, it is not because I mean to seek a quarrel with honourable (members). On the contrary, I say, let pre-war feuds die; let personal quarrels be forgotten, and let us keep our hatreds for the common enemy. Let party interest be ignored, let all our energies be harnessed, let the whole ability and forces of the nation be hurled into the struggle, and let all the strong horses be pulling on the collar. At no time in the last war were we in greater peril than we are now, and I urge the House strongly to deal with these matters not in a precipitate vote, ill debated and on a widely discursive field, but in grave time and due time in accordance with the dignity of Parliament.

Churchill sat down but the rowdiness continued with catcalls from both sides of the House and Chips Channon later wrote that it was "like Bedlam".[84] Labour's Hugh Dalton wrote that a good deal of riot developed, some of it rather stupid, towards the end of the speech.[85]

Division

editAt 23:00, the Speaker rose to put the question "that this House do now adjourn". There was minimal dissent and he announced the division, calling for the Lobby to be cleared. The division was in effect a no confidence motion or, as Churchill called it in his closing speech, a vote of censure. Of the total 615 members, it has been estimated that more than 550 were present when the division was called but only 481 voted.[86]

The government's notional majority was 213, but 41 members who normally supported the government voted with the Opposition while an estimated 60 other Conservatives deliberately abstained. The government still won the vote by 281 to 200, but their majority was reduced to 81. Jenkins says that would have been perfectly sustainable in most circumstances, but not when Britain was losing the war and it was clear that unity and leadership were so obviously lacking. In these circumstances, the reversal was devastating and Chamberlain left the chamber pale and grim.[85]

Among the Conservatives, Chips Channon and other Chamberlain supporters shouted "Quislings" and "Rats" at the rebels, who replied with taunts of "Yes-men".[87][88] Labour's Josiah Wedgwood led the singing of "Rule Britannia", joined by Conservative rebel Harold Macmillan of the Noes; that gave way to cries of "Go!" as Chamberlain left the Chamber.[89] Amery, Keyes, Macmillan and Boothby were among the rebels voting with Labour. Others were Nancy Astor, John Profumo, Quintin Hogg, Leslie Hore-Belisha and Edward Spears but not some expected dissidents such as Duncan Sandys, who abstained, and Brendan Bracken who, in Jenkins' words, "followed [Churchill's] example rather than his interest and voted with the government".[85] Colville in his diary said the government were "fairly satisfied" but acknowledged that reconstruction of the Cabinet was necessary. He wrote that "the shock they have received may be a healthy one".[90]

9 May: third day and conclusion

editThe debate continued into a third day but, with the division having been held at the end of the second day, the final day was really a matter of wrapping up. Starting at 15:18, there were only four speakers and the last of them was Lloyd George who spoke mostly about his own time as prime minister in the First World War and at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference. He concluded by blaming the democracies for not carrying out the pledges made at that time with the result that Nazism had arisen in Germany. When he finished, shortly before 16:00, the question "that this House do now adjourn" was raised and agreed to, thus concluding the Norway Debate.[91]

Aftermath

editOn 9 and 10 May, Chamberlain attempted to form a coalition government with Labour and Liberal participation. They indicated an unwillingness to serve under him but said they probably would join the government if another Conservative became prime minister. When Germany began its western offensive on the morning of 10 May, Chamberlain seriously considered staying on but, after receiving final confirmation from Labour that they required his resignation, he decided to stand down and advised the King to send for Churchill as his successor.[92][93]

Gaining the support of both Labour and the Liberals, Churchill formed a coalition government. His war cabinet at first consisted of himself, Attlee, Greenwood, Chamberlain and Halifax.[94] The coalition lasted until the defeat of Nazi Germany in May 1945. On 23 May 1945, Labour left the coalition to begin their general election campaign and Churchill resigned as prime minister. The King asked him to form a new government, known as the Churchill caretaker ministry, until the election was held in July. Churchill agreed and his new ministry, essentially a Conservative one, held office for the next two months until it was replaced by the first Attlee ministry after Labour's election victory.[95][96]

Place in parliamentary culture

editThe Norway debate is regarded as a high point in British parliamentary history, coming as it did at a time when Great Britain faced its gravest danger. The former prime minister, David Lloyd George, said the debate was the most momentous in the history of Parliament. The future prime minister, Harold Macmillan, believed that the debate changed British history, perhaps world history.[97]

In his biography of Churchill, Roy Jenkins describes the debate as "by a clear head both the most dramatic and the most far-reaching in its consequences of any parliamentary debate of the twentieth century".[98] He compares it with "its nineteenth-century rivals" (e.g., the Don Pacifico debate of 1850) and concludes that "even more followed from the 1940 debate" as it transformed the history of the next five years.[98]

Andrew Marr wrote that the debate was "one of the greatest parliamentary moments ever and little about it was inevitable". The plotters against Chamberlain succeeded despite being deprived of their natural leader, since Churchill was in the cabinet and obliged to defend it.[99] Marr notes the irony of Amery's closing words which were originally directed against Parliament by Cromwell, who was speaking for military dictatorship.[100]

When asked to choose the most historic and memorable speech for a volume commemorating the centenary of Hansard as an official report of the House of Commons, former Speaker Betty Boothroyd chose Amery's speech in the debate, "Amery, by elevating patriotism above party, showed the backbencher's power to help change the course of history".[101]

Notes

edit- ^ In parliamentary procedure, a division of the House (or assembly) is a method of taking a vote that physically counts members voting. In the UK Parliament, the members divide into two lobbies to record their votes in favour (the Ayes lobby) or against (the Noes lobby) the motion.

- ^ Unless otherwise referenced, quotes in this article are from the full text of the debate as given in Hansard or the Official Report, Fifth Series, volume 360, columns 1073–1196 and 1251–1366.

- ^ The account of the debate in Martin Gilbert's multi-volume biography of Churchill gives Sinclair a markedly different speech, which in fact is that made by Arthur Greenwood later in the debate.

- ^ Cromwell said 'gentlemen' not 'they' but meant the enemy, as did Amery.

Citations

edit- ^ Marwick 1976, p. 13.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, p. 571.

- ^ Hinsley et al. 1979, pp. 119–125.

- ^ Buckley 1977, pp. 25–26.

- ^ "Norway Situation". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, cols 906–913. 2 May 1940. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ "Business of the House". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 914. 2 May 1940. Retrieved 22 May 2019.

- ^ Colville 1985, p. 135.

- ^ "Preamble". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1015. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Private Business". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, cols 1015–1073. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Adjournment Motion". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1073. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Conduct of the War – Chamberlain". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1074. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 262.

- ^ Nicolson 1967, p. 76.

- ^ a b c Shakespeare 2017, p. 263.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Chamberlain". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1082. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2001, p. 577.

- ^ a b Shakespeare 2017, p. 264.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Attlee". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1088. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Attlee". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1092. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, pp. 577–578.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Attlee". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1093. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Attlee". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1094. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 265.

- ^ a b c "Conduct of the War – Sinclair". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, cols 1094–1106. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 4 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d Shakespeare 2017, p. 266.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Page Croft". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1106. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Wedgwood". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1116. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Wedgwood". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1124. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Edel, Leon (3 December 1966). "The Price of Peace Was War". Saturday Review: 53–54.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Wedgwood". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1119. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, pp. 266–267.

- ^ a b Shakespeare 2017, p. 268.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, p. 578.

- ^ Nicolson 1967, p. 77.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 269.

- ^ Nicolson 1967, p. 77

- ^ a b c Shakespeare 2017, p. 270.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Bellenger". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1140. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 3 May 2019.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 271.

- ^ a b Shakespeare 2017, p. 272.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 273.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Amery". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1143. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ a b Shakespeare 2017, p. 274.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Amery". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1149. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ a b Shakespeare 2017, p. 276.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Amery". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1150. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 11 May 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Jenkins 2001, p. 579.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 278.

- ^ "Conduct of the War. (Hansard, 7 May 1940)". api.parliament.uk. Retrieved 4 December 2018.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Boothby". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1152. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Milner". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1161. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Winterton". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1164. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Greenwood". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1178. 7 May 1940. Retrieved 12 May 2019.

- ^ a b Shakespeare 2017, p. 281.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Morrison". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1251. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, pp. 284–285.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Chamberlain". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1265. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Nicolson 1967, p. 78.

- ^ a b Shakespeare 2017, p. 285.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Hoare". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1277. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 287.

- ^ a b "Conduct of the War – Lloyd George". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1278. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 15 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Lloyd George". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1279. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Lloyd George". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1282. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Churchill". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1283. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b c "Conduct of the War – Lloyd George". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1283. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Jenkins 2001, p. 580.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 288.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 289.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Chamberlain". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1283. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, pp. 289–290.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Other speakers". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, cols 1283–1333. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Alexander". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1348. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2001, p. 581.

- ^ a b c Shakespeare 2017, p. 299.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Alexander". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1340. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 19 May 2019.

- ^ a b c Shakespeare 2017, p. 300.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Churchill". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1349. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Churchill". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1352. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Churchill". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1358. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Churchill". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1360. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ a b "Conduct of the War – Churchill". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1361. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Churchill". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1362. 8 May 1940. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 302.

- ^ a b c Jenkins 2001, p. 582.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 21.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 308.

- ^ Jefferys, Kevin (1995). The Churchill Coalition and Wartime Politics, 1940–1945. Manchester University Press. p. 24. ISBN 978-07-19025-60-0.

- ^ Nicolson, p. 79; others say Harold Macmillan led the singing. Channon wrote that Macmillan began singing after Wedgwood.

- ^ Colville 1985, pp. 138–139.

- ^ "Conduct of the War – Conclusion". Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 360, col. 1496. 9 May 1940. Retrieved 16 May 2019.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, pp. 583–588.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 361–399.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, pp. 587–588.

- ^ Gilbert 1991, p. 855.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, pp. 798–799.

- ^ Shakespeare 2017, p. 7.

- ^ a b Jenkins 2001, pp. 576–577.

- ^ Marr 2009, p. 366.

- ^ Marr 2009, p. 367.

- ^ Betty Boothroyd, "Ferocious attack that spelt the end for Chamberlain and opened the way for Churchill", in "Official Report [Hansard]", Centenary Volume, House of Commons 2009, p. 91.

General and cited references

edit- Buckley, Christopher (1977). Norway, The Commandos, Dieppe. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-772194-4.

- Churchill, Winston (1948). The Second World War. Volume I: The Gathering Storm. London: Cassel. OCLC 818817867.

- Colville, John (1985). The Fringes of Power, Volume One: September 1939 to September 1941. Sevenoaks: Hodder & Stoughton Ltd. ISBN 978-0-34-040269-6.

- Gilbert, Martin (1983). Winston S. Churchill, Vol. 6: Finest Hour, 1939–1941. Heinemann. ISBN 978-0-43-413014-6.

- Gilbert, Martin (1991). Churchill: A Life. London: Heinemann. ISBN 978-04-34291-83-0.

- Hinsley, F. H.; Thomas, E. E.; Ransom, C. F. G.; Knight, R. C. (1979). British Intelligence in the Second World War: Its Influence on Strategy and Operations. Vol. I. London: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630933-4 – via Archive.org.

- Jenkins, Roy (2001). Churchill. London: MacMillan Press. ISBN 978-0-33-048805-1.

- Marr, Andrew (2009). The Making of Modern Britain. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-33-051099-8.

- Marwick, Arthur (1976). The Home Front: The British and the Second World War. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-50-027114-8.

- Nicolson, Harold (1967). Nigel Nicolson (ed.). The Diaries and Letters of Harold Nicolson. Volume II: The War Years, 1939–1945. New York: Atheneum. LCCN 66023571.

- Rhodes James, Robert (1971). Robert Boothby: A Portrait of Churchill's Ally. New York: Viking. ISBN 978-0-67-082886-9.

- Shakespeare, Nicholas (2017). Six Minutes in May. London: Vintage. ISBN 978-1-78-470100-0.

- Wheeler-Bennett, John (1958). King George VI, His Life and Reign. London: Macmillan. OCLC 655565202.

Further reading

edit- Kelly, Bernard (2009). "Drifting Towards War: The British Chiefs of Staff, the USSR and the Winter War, November 1939 – March 1940", Contemporary British History, (2009) 23:3 pp. 267–291, doi:10.1080/13619460903080010

- Redihan, Erin (2013). "Neville Chamberlain and Norway: The Trouble with 'A Man of Peace' in a Time of War". New England Journal of History (2013) 69#1/2 pp. 1–18.

External links

edit- "1940: Action this Day; Finest Hour: September 1940–1941". A Daily Chronicle of Churchill's Life. The Churchill Centre. Archived from the original on 4 June 2009. Retrieved 18 November 2007.

- Churchill & The Norway Debate – UK Parliament Living Heritage