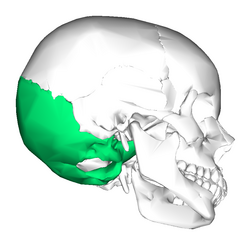

The occipital bone (/ˌɒkˈsɪpɪtəl/) is a cranial dermal bone and the main bone of the occiput (back and lower part of the skull). It is trapezoidal in shape and curved on itself like a shallow dish. The occipital bone overlies the occipital lobes of the cerebrum. At the base of the skull in the occipital bone, there is a large oval opening called the foramen magnum, which allows the passage of the spinal cord.

| Occipital bone | |

|---|---|

Position of occipital bone | |

Animation of the occipital bone | |

| Details | |

| Articulations | The two parietals, the two temporals, the sphenoid, and the atlas |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | os occipitale |

| MeSH | D009777 |

| TA98 | A02.1.04.001 |

| TA2 | 552 |

| FMA | 52735 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

Like the other cranial bones, it is classed as a flat bone. Due to its many attachments and features, the occipital bone is described in terms of separate parts. From its front to the back is the basilar part, also called the basioccipital, at the sides of the foramen magnum are the lateral parts, also called the exoccipitals, and the back is named as the squamous part. The basilar part is a thick, somewhat quadrilateral piece in front of the foramen magnum and directed towards the pharynx. The squamous part is the curved, expanded plate behind the foramen magnum and is the largest part of the occipital bone.

Due to its embryonic derivation from paraxial mesoderm (as opposed to neural crest, from which many other craniofacial bones are derived), it has been posited that "the occipital bone as a whole could be considered as a giant vertebra enlarged to support the brain."[1]

Structure

editThe occipital bone, like the other seven cranial bones, has outer and inner layers (also called plates or tables) of cortical bone tissue between which is the cancellous bone tissue known in the cranial bones as diploë. The bone is especially thick at the ridges, protuberances, condyles, and anterior part of the basilar part; in the inferior cerebellar fossae it is thin, semitransparent, and without diploë.

Outer surface

editNear the middle of the outer surface of the squamous part of the occipital (the largest part) there is a prominence – the external occipital protuberance. The highest point of this is called the inion.

From the inion, along the midline of the squamous part until the foramen magnum, runs a ridge – the external occipital crest (also called the medial nuchal line) and this gives attachment to the nuchal ligament.

Running across the outside of the occipital bone are three curved lines and one line (the medial line) that runs down to the foramen magnum. These are known as the nuchal lines which give attachment to various ligaments and muscles. They are named as the highest, superior and inferior nuchal lines. The inferior nuchal line runs across the midpoint of the median nuchal line. The area above the highest nuchal line is termed the occipital plane and the area below this line is termed the nuchal plane.

Inner surface

editThe inner surface of the occipital bone forms the base of the posterior cranial fossa. The foramen magnum is a large hole situated in the middle, with the clivus, a smooth part of the occipital bone travelling upwards in front of it. The median internal occipital crest travels behind it to the internal occipital protuberance, and serves as a point of attachment to the falx cerebri.

To the sides of the foramen sitting at the junction between the lateral and base of the occipital bone are the hypoglossal canals. Further out, at each junction between the occipital and petrous portion of the temporal bone lies a jugular foramen.[2]

The inner surface of the occipital bone is marked by dividing lines as shallow ridges, that form four fossae or depressions. The lines are called the cruciform (cross-shaped) eminence.

At the midpoint where the lines intersect a raised part is formed called the internal occipital protuberance. From each side of this eminence runs a groove for the transverse sinuses.

There are two midline skull landmarks at the foramen magnum. The basion is the most anterior point of the opening and the opisthion is the point on the opposite posterior part. The basion lines up with the dens.

Foramen magnum

editThe foramen magnum (Latin: large hole) is a large oval foramen longest front to back; it is wider behind than in front where it is encroached upon by the occipital condyles. The clivus, a smooth bony section, travels upwards on the front surface of the foramen, and the median internal occipital crest travels behind it.[3]

Through the foramen passes the medulla oblongata and its membranes, the accessory nerves, the vertebral arteries, the anterior and posterior spinal arteries, the tectorial membrane and the alar ligaments.

Angles

editThe superior angle of the occipital bone articulates with the occipital angles of the parietal bones and, in the fetal skull, corresponds in position with the posterior fontanelle.

The lateral angles are situated at the extremities of the groove for the transverse sinuses: each is received into the interval between the mastoid angle of the parietal bone, and the mastoid portion of the temporal bone.

The inferior angle is fused with the body of the sphenoid bone.

Borders

editThe superior borders extend from the superior to the lateral angles: they are deeply serrated for articulation with the occipital borders of the parietals, and form by this union the lambdoidal suture.

The inferior borders extend from the lateral angles to the inferior angle; the upper half of each articulates with the mastoid portion of the corresponding temporal, the lower half with the petrous part of the same bone.

These two portions of the inferior border are separated from one another by the jugular process, the notch on the anterior surface of which forms the posterior part of the jugular foramen.

Sutures

edit-

Lambdoid suture

-

Occipitomastoid suture

The lambdoid suture joins the occipital bone to the parietal bones.

The occipitomastoid suture joins the occipital bone and mastoid portion of the temporal bone.

The sphenobasilar suture joins the basilar part of the occipital bone and the back of the sphenoid bone body.

The petrous-basilar suture joins the side edge of the basilar part of the occipital bone to the petrous-part of the temporal bone.

Development

editThe occipital plane [Fig. 3] of the squamous part of the occipital bone is developed in membrane, and may remain separate throughout life when it constitutes the interparietal bone; the rest of the bone is developed in cartilage.

The number of nuclei for the occipital plane is usually given as four, two appearing near the middle line about the second month, and two some little distance from the middle line about the third month of fetal life.

The nuchal plane of the squamous part is ossified from two centers, which appear about the seventh week of fetal life and soon unite to form a single piece.

Union of the upper and lower portions of the squamous part takes place in the third month of fetal life.

An occasional centre (Kerckring) appears in the posterior margin of the foramen magnum during the fifth month; this forms a separate ossicle (sometimes double) which unites with the rest of the squamous part before birth.

Each of the lateral parts begins to ossify from a single center during the eighth week of fetal life. The basilar portion is ossified from two centers, one in front of the other; these appear about the sixth week of fetal life and rapidly coalesce.

The occipital plane is said to be ossified from two centers and the basilar portion from one.

About the fourth year the squamous part and the two lateral parts unite, and by about the sixth year the bone consists of a single piece. Between the 18th and 25th years the occipital and sphenoid bone become united, forming a single bone.

Clinical significance

editTrauma to the occiput can cause a fracture of the base of the skull, called a basilar skull fracture. The basion-dens line as seen on a radiograph is the distance between the basion and the top of the dens, used in the diagnosis of dissociation injuries.[4]

Genetic disorders can cause a prominent occiput as found in Edwards syndrome, and Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome.

The identification of the location of the fetal occiput is important in delivery.

Etymology

editOccipital stems from Latin occiput "back of the skull", from ob "against, behind" + caput "head". Distinguished from sinciput (anterior part of the skull).[5]

Other animals

editIn many animals these parts stay separate throughout life; for example, in the dog as four parts: squamous part (supraoccipital); lateral parts–left and right parts (exoccipital); basilar part (basioccipital).

The occipital bone is part of the endocranium, the most basal portion of the skull. In Chondrichthyes and Agnatha, the occipital does not form as a separate element, but remains part of the chondrocranium throughout life. In most higher vertebrates, the foramen magnum is surrounded by a ring of four bones.

The basioccipital lies in front of the opening, the two exoccipital condyles lie to either side, and the larger supraoccipital lies to the posterior, and forms at least part of the rear of the cranium. In many bony fish and amphibians, the supraoccipital is never ossified, and remains as cartilage throughout life. In primitive forms the basioccipital and exoccipitals somewhat resemble the centrum and neural arches of a vertebra, and form in a similar manner in the embryo. Together, these latter bones usually form a single concave circular condyle for the articulation of the first vertebra.[6]

In mammals, however, the condyle has divided in two, a pattern otherwise seen only in a few amphibians.

Most mammals also have a single fused occipital bone, formed from the four separate elements around the foramen magnum, along with the paired postparietal bones that form the rear of the cranial roof in other vertebrates.[6]

Additional images

edit-

Position of occipital bone (shown in green). Animation.

-

Outer surface

-

Inner surface. Frontal bone and parietal bones are removed.

-

Occipital bone

-

Occipital bone

-

Median sagittal section through the occipital bone and first three cervical vertebræ

-

Basilar part

-

Occipital bone

See also

editReferences

editBooks

editThis article incorporates text in the public domain from page 129 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- Susan Standring; Neil R. Borley; et al., eds. (2008). Gray's anatomy: the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

Citations

edit- ^ Nie, Xuguang (2005). "Cranial base in craniofacial development: Developmental features, influence on facial growth, anomaly, and molecular basis". Acta Odontologica Scandinavica. 63 (3): 130. doi:10.1080/00016350510019847. PMID 16191905. S2CID 1091809 – via Taylor & Francis Online.

- ^ Gray's Anatomy 2008, p. 424-425.

- ^ Gray's Anatomy 2008, p. 425.

- ^ Hacking, Craig. "Basion-dens interval | Radiology Reference Article | Radiopaedia.org". radiopaedia.org. Retrieved 5 December 2016.

- ^ "occipital" A Dictionary of Zoology. Ed. Michael Allaby. Oxford University Press 2009

- ^ a b Romer, Alfred Sherwood; Parsons, Thomas S. (1977). The Vertebrate Body. Philadelphia, PA: Holt-Saunders International. pp. 221–244. ISBN 0-03-910284-X.

External links

edit- Media related to Occipital bones at Wikimedia Commons