Old Norse religion, also known as Norse paganism, is a branch of Germanic religion which developed during the Proto-Norse period, when the North Germanic peoples separated into a distinct branch of the Germanic peoples. It was replaced by Christianity and forgotten during the Christianisation of Scandinavia. Scholars reconstruct aspects of North Germanic Religion by historical linguistics, archaeology, toponymy, and records left by North Germanic peoples, such as runic inscriptions in the Younger Futhark, a distinctly North Germanic extension of the runic alphabet. Numerous Old Norse works dated to the 13th-century record Norse mythology, a component of North Germanic religion.

Old Norse religion was polytheistic, entailing a belief in various gods and goddesses. These deities in Norse mythology were divided into two groups, the Æsir and the Vanir, who in some sources were said to have engaged in an ancient war until realizing that they were equally powerful. Among the most widespread deities were the gods Odin and Thor. This world was inhabited also by various other mythological races, including jötnar, dwarfs, elves, and land-wights. Norse cosmology revolved around a world tree known as Yggdrasil, with various realms existing alongside that of humans, named Midgard. These include multiple afterlife realms, several of which are controlled by a particular deity.

Transmitted through oral culture rather than through codified texts, Old Norse religion focused heavily on ritual practice, with kings and chiefs playing a central role in carrying out public acts of sacrifice. Various cultic spaces were used; initially, outdoor spaces such as groves and lakes were typically selected, but after the third century CE cult houses seem to also have been purposely built for ritual activity, although they were never widespread. Norse society also contained practitioners of Seiðr, a form of sorcery that some scholars describe as shamanistic. Various forms of burial were conducted, including both inhumation and cremation, typically accompanied by a variety of grave goods.

Throughout its history, varying levels of trans-cultural diffusion occurred among neighbouring peoples, such as the Sami and Finns. By the 12th century, Old Norse religion had been replaced by Christianity, with elements continuing into Scandinavian folklore. A revival of interest in Old Norse religion occurred amid the romanticist movement of the 19th century, during which it inspired a range of artworks. Academic research into the subject began in the early 19th century, initially influenced by the pervasive romanticist sentiment.

Terminology

editThe archaeologist Anders Andrén noted that "Old Norse religion" is "the conventional name" applied to the pre-Christian religions of Scandinavia.[1] See for instance[2] other terms used by scholarly sources include "pre-Christian Norse religion",[3] "Norse religion",[4] "Norse paganism",[5] "Nordic paganism",[6] "Scandinavian paganism",[7] "Scandinavian heathenism",[8] "Scandinavian religion",[9] "Northern paganism",[10] "Northern heathenism",[11] "North Germanic religion",[a][b] or "North Germanic paganism".[c][d] This Old Norse religion can be seen as part of a broader Germanic religion found across linguistically Germanic Europe; of the different forms of this Germanic religion, that of the Old Norse is the best-documented.[12]

Rooted in ritual practice and oral tradition,[12] Old Norse religion was fully integrated with other aspects of Norse life, including subsistence, warfare, and social interactions.[13] Open codifications of Old Norse beliefs were either rare or non-existent.[14] The practitioners of this belief system themselves had no term meaning "religion", which was only introduced with Christianity.[15] Following Christianity's arrival, Old Norse terms that were used for the pre-Christian systems were forn sið ("old custom") or heiðinn sið ("heathen custom"),[15] terms which suggest an emphasis on rituals, actions, and behaviours rather than belief itself.[16] The earliest known usage of the Old Norse term heiðinn is in the poem Hákonarmál; its uses here indicates that the arrival of Christianity has generated consciousness of Old Norse religion as a distinct religion.[17]

Old Norse religion has been classed as an ethnic religion,[18] and as a "non-doctrinal community religion".[13] It varied across time, in different regions and locales, and according to social differences.[19] This variation is partly due to its transmission through oral culture rather than codified texts.[20] For this reason, the archaeologists Andrén, Kristina Jennbert, and Catharina Raudvere stated that "pre-Christian Norse religion is not a uniform or stable category",[21] while the scholar Karen Bek-Pedersen noted that the "Old Norse belief system should probably be conceived of in the plural, as several systems".[22] The historian of religion Hilda Ellis Davidson stated that it would have ranged from manifestations of "complex symbolism" to "the simple folk-beliefs of the less sophisticated".[23]

During the Viking Age, the Norse likely regarded themselves as a more or less unified entity through their shared Germanic language, Old Norse.[24] The scholar of Scandinavian studies Thomas A. DuBois said Old Norse religion and other pre-Christian belief systems in Northern Europe must be viewed as "not as isolated, mutually exclusive language-bound entities, but as broad concepts shared across cultural and linguistic lines, conditioned by similar ecological factors and protracted economic and cultural ties".[25] During this period, the Norse interacted closely with other ethnocultural and linguistic groups, such as the Sámi, Balto-Finns, Anglo-Saxons, Greenlandic Inuit, and various speakers of Celtic and Slavic languages.[26] Economic, marital, and religious exchange occurred between the Norse and many of these other groups.[26] Enslaved individuals from the British Isles were common throughout the Nordic world during the Viking Age.[27] Different elements of Old Norse religion had different origins and histories; some aspects may derive from deep into prehistory, others only emerging following the encounter with Christianity.[28]

Sources

editIn Hilda Ellis Davidson's words, present-day knowledge of Old Norse religion contains "vast gaps", and we must be cautious and avoid "bas[ing] wild assumptions on isolated details".[29]

Scandinavian textual sources

editA few runic inscriptions with religious content survive from Scandinavia, particularly asking Thor to hallow or protect a memorial stone;[30] carving his hammer on the stone also served this function.[31]

In contrast to the few runic fragments, a considerable body of literary and historical sources survive in Old Norse manuscripts using the Latin script, all of which were created after the Christianisation of Scandinavia, the majority in Iceland. The first extensive Nordic textual source for the Old Norse Religion was the Poetic Edda. Some of the poetic sources, in particular, the Poetic Edda and skaldic poetry, may have been originally composed by heathens, and Hávamál contains both information on heathen mysticism[32] and what Ursula Dronke referred to as "a round-up of ritual obligations".[33] In addition there is information about pagan beliefs and practices in the sagas, which include both historical sagas such as Snorri Sturluson's Heimskringla and the Landnámabók, recounting the settlement and early history of Iceland, and the so-called sagas of Icelanders concerning Icelandic individuals and groups; there are also more or less fantastical legendary sagas. Many skaldic verses are preserved in sagas. Of the originally heathen works, we cannot know what changes took place either during oral transmission or as a result of their being recorded by Christians;[34][35] the sagas of Icelanders, in particular, are now regarded by most scholars as more or less historical fiction rather than as detailed historical records.[36] A large amount of mythological poetry has undoubtedly been lost.[37]

One important written source is Snorri's Prose Edda, which incorporates a manual of Norse mythology for the use of poets in constructing kennings; it also includes numerous citations, some of them the only record of lost poems,[38] such as Þjóðólfr of Hvinir's Haustlöng. Snorri's Prologue eumerises the Æsir as Trojans, deriving Æsir from Asia, and some scholars have suspected that many of the stories that we only have from him are also derived from Christian medieval culture.[39]

Non-Scandinavian textual sources

editAdditional sources remain by non-Scandinavians writing in languages other than Old Norse. The first non-Scandinavian textual source for the Old Norse Religion was Tacitus' book, the Germania, which dates back to around 100 CE[40] and describes religious practices of several Germanic peoples, but has little coverage of Scandinavia. In the Middle Ages, several Christian commentators also wrote about Scandinavian paganism, mostly from a hostile perspective.[40] The best known of these are Adam of Bremen's Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum (History of the Bishops of Hamburg), written between 1066 and 1072, which includes an account of the temple at Uppsala,[41][42] and Saxo Grammaticus' 12th-century Gesta Danorum (History of the Danes), which includes versions of Norse myths and some material on pagan religious practices.[43][44] In addition, Muslim Arabs wrote accounts of Norse people they encountered, the best known of which is Ibn Fadlan's 10th-century Risala, an account of Volga Viking traders that includes a detailed description of a ship burial.[45]

Archaeological and toponymic evidence

editSince the literary evidence that represents Old Norse sources were recorded by Christians, archaeological evidence, especially of religious sites and burials is of great importance, particularly as a source of information on Norse religion before the conversion.[46][47] Many aspects of material culture—including settlement locations, artefacts and buildings—may cast light on beliefs, and archaeological evidence regarding religious practices indicates chronological, geographic and class differences far greater than are suggested by the surviving texts.[21]

Place names are an additional source of evidence. Theophoric place names, including instances where a pair of deity names occur near, provide an indication of the importance of the religion of those deities in different areas, dating back to before our earliest written sources. The toponymic evidence shows considerable regional variation,[48][49] and some deities, such as Ullr and Hǫrn, occur more frequently,[48] than Odin place-names occur, in other locations.[50][49]

Some place-names contain elements indicating that they were sites of religious activity: those formed with -vé, -hörgr, and -hof, words for religious sites of various kinds,[51] and also likely those formed with -akr or -vin, words for "field", when coupled with the name of a deity. Magnus Olsen developed a typology of such place names in Norway, from which he posited a development in pagan worship from groves and fields toward the use of temple buildings.[52]

Personal names are also a source of information on the popularity of certain deities; for example, Thor's name was an element in the names of both men and women, particularly in Iceland.[53]

Historical development

editIron Age origins

editAndrén described Old Norse religion as a "cultural patchwork" which emerged under a wide range of influences from earlier Scandinavian religions. It may have had links to Nordic Bronze Age: while the putatively solar-oriented belief system of Bronze Age Scandinavia is believed to have died out around 500 BCE, several Bronze Age motifs—such as the wheel cross—reappear in later Iron Age contexts.[10] It is often regarded as having developed from earlier religious belief systems found among the Germanic Iron Age peoples.[54] The Germanic languages likely emerged in the first millennium BCE in present-day Denmark or northern Germany, after which they spread; several of the deities in Old Norse religion have parallels among other Germanic societies.[55] The Scandinavian Iron Age began around 500 to 400 BCE.[56]

Archaeological evidence is particularly important for understanding these early periods.[57] Accounts from this time were produced by Tacitus; according to the scholar Gabriel Turville-Petre, Tacitus' observations "help to explain" later Old Norse religion.[58] Tacitus described the Germanic peoples as having priests, open-air sacred sites, and seasonal sacrifices and feasts.[59] Tacitus notes that the Germanic peoples were polytheistic and mentions some of their deities trying to perceive them through Roman equivalents, so Romans could try to understand.[60]

Viking Age expansion

editDuring the Viking Age, Norse people left Scandinavia and settled elsewhere throughout Northwestern Europe. Some of these areas, such as Iceland, the Orkney and Shetland Islands, and the Faroe Islands, were hardly populated, whereas other areas, such as England, Southwest Wales, Scotland, the Western Isles, Isle of Man, and Ireland, were already heavily populated.[61]

In the 870s, Norwegian settlers left their homeland and colonized Iceland, bringing their belief system with them.[62] Place-name evidence suggests that Thor was the most popular god on the island,[63] although there are also saga accounts of devotés of Freyr in Iceland,[64] including a "priest of Freyr" in the later Hrafnkels saga.[65] There are no place-names connected to Odin on the island.[66] Unlike other Nordic societies, Iceland lacked a monarchy and thus a centralising authority which could enforce religious adherence;[67] there were both Old Norse and Christian communities from the time of its first settlement.[68]

Scandinavian settlers brought Old Norse religion to Britain in the latter decades of the ninth century.[69] Several British place-names indicate possible religious sites;[70] for instance, Roseberry Topping in North Yorkshire was known as Othensberg in the twelfth century, a name deriving from the Old Norse Óðinsberg ("Hill of Óðin").[71] Several place-names also contain Old Norse references to religious entities, such as alfr, skratii, and troll.[72] The English church found itself in need of conducting a new conversion process to Christianise this incoming population.[73]

Christianisation and decline

editThe Nordic world first encountered Christianity through its settlements in the already Christian British Isles and through trade contacts with the eastern Christians in Novgorod and Byzantium.[74] By the time Christianity arrived in Scandinavia it was already the accepted religion across most of Europe.[75] It is not well understood how the Christian institutions converted these Scandinavian settlers, in part due to a lack of textual descriptions of this conversion process equivalent to Bede's description of the earlier Anglo-Saxon conversion.[76] However, it appears that the Scandinavian migrants had converted to Christianity within the first few decades of their arrival.[further explanation needed][77] After Christian missionaries from the British Isles—including figures like St Willibrord, St Boniface, and Willehad—had travelled to parts of northern Europe in the eighth century,[78] Charlemagne pushed for Christianisation in Denmark, with Ebbo of Rheims, Halitgar of Cambrai, and Willeric of Bremen proselytizing in the kingdom during the ninth century.[79] The Danish king Harald Klak converted (826), likely to secure his political alliance with Louis the Pious against his rivals for the throne.[80] The Danish monarchy reverted to Old Norse religion under Horik II (854 – c. 867).[81]

The Norwegian king Hákon the Good had converted to Christianity while in England. On returning to Norway, he kept his faith largely private but encouraged Christian priests to preach among the population; some pagans were angered and—according to Heimskringla—three churches built near Trondheim were burned down.[82] His successor, Harald Greycloak, was also a Christian but similarly had little success in converting the Norwegian population to his religion.[83] Haakon Sigurdsson later became the de facto ruler of Norway, and although he agreed to be baptised under pressure from the Danish king and allowed Christians to preach in the kingdom, he enthusiastically supported pagan sacrificial customs, asserting the superiority of the traditional deities and encouraging Christians to return to their veneration.[84] His reign (975–995) saw the emergence of a "state paganism", an official ideology which bound together Norwegian identity with pagan identity and rallied support behind Haakon's leadership.[85] Haakon was killed in 995 and Olaf Tryggvason, the next king, took power and enthusiastically promoted Christianity; he forced high-status Norwegians to convert, destroyed temples, and killed those he called 'sorcerers'.[86] Sweden was the last Scandinavian country to officially convert;[75] although little is known about the process of Christianisation, it is known that the Swedish kings had converted by the early 11th century and that the country was fully Christian by the early 12th.[87]

Olaf Tryggvason sent a Saxon missionary, Þangbrandr, to Iceland. Many Icelanders were angered by Þangbrandr's proselytising, and he was outlawed after killing several poets who insulted him.[88] Animosity between Christians and pagans on the island grew, and at the Althing in 998 both sides blasphemed each other's gods.[89] In an attempt to preserve unity, at the Althing in 999, an agreement was reached that the Icelandic law would be based on Christian principles, albeit with concessions to the pagan community. Private, albeit not public, pagan sacrifices and rites were to remain legal.[90]

Across Germanic Europe, conversion to Christianity was closely connected to social ties; mass conversion was the norm, rather than individual conversion.[91] A primary motivation for kings converting was the desire for support from Christian rulers, whether as money, imperial sanction, or military support.[91] Christian missionaries found it difficult convincing Norse people that the two belief systems were mutually exclusive;[92] the polytheistic nature of Old Norse religion allowed its practitioners to accept Jesus Christ as one god among many.[93] The encounter with Christianity could also stimulate new and innovative expressions of pagan culture, for instance through influencing various pagan myths.[94] As with other Germanic societies, syncretisation between incoming and traditional belief systems took place.[95] For those living in isolated areas, pre-Christian beliefs likely survived longer,[96] while others continued as survivals in folklore.[96]

Post-Christian survivals

editBy the 12th century, Christianity was firmly established across Northwestern Europe.[97] For two centuries, Scandinavian ecclesiastics continued to condemn paganism, although it is unclear whether it still constituted a viable alternative to Christian dominance.[98] These writers often presented paganism as being based on deceit or delusion;[99] some stated that the Old Norse gods had been humans falsely euhemerised as deities.[100]

Old Norse mythological stories survived in oral culture for at least two centuries, being recorded in the 13th century.[101] How this mythology was passed down is unclear; it is possible that pockets of pagans retained their belief system throughout the 11th and 12th centuries, or that it had survived as a cultural artefact passed down by Christians who retained the stories while rejecting any literal belief in them.[101] The historian Judith Jesch suggested that following Christianisation, there remained a "cultural paganism", the re-use of pre-Christian myth "in certain cultural and social contexts" that are officially Christian.[102] For instance, Old Norse mythological themes and motifs appear in poetry composed for the court of Cnut the Great, an eleventh-century Christian Anglo-Scandinavian king.[103] Saxo is the earliest medieval figure to take a revived interest in the pre-Christian beliefs of his ancestors, doing so not out of a desire to revive their faith but out of historical interest.[104] Snorri was also part of this revived interest, examining pagan myths from his perspective as a cultural historian and mythographer.[105] As a result, Norse mythology "long outlasted any worship of or belief in the gods it depicts".[106] There remained, however, remnants of Norse pagan rituals for centuries after Christianity became the dominant religion in Scandinavia (see Trollkyrka). Old Norse gods continued to appear in Swedish folklore up until the early 20th century. There are documented accounts of encounters with both Thor and Odin, along with a belief in Freja's power over fertility.[107]

Beliefs

editNorse mythology, stories of the Norse deities, is preserved in Eddic poetry and in Snorri Sturluson's guide for skalds, the Poetic Edda. Depictions of some of these stories can be found on picture stones in Gotland and in other visual records including some early Christian crosses, which attests to how widely known they were.[108] The myths were transmitted purely orally until the end of the period, and were subject to variation; one key poem, "Vǫluspá", is preserved in two variant versions in different manuscripts,[e] and Snorri's retelling of the myths sometimes varies from the other textual sources that are preserved.[109] There was no single authoritative version of a particular myth, and variation over time and from place to place is presumed, rather than "a single unified body of thought".[110][104] In particular, there may have been influences from interactions with other peoples, including northern Slavs, Finns, and Anglo-Saxons,[111] and Christian mythology exerted an increasing influence.[110][112]

Deities

editOld Norse religion was polytheistic, with many anthropomorphic gods and goddesses, who express human emotions and in some cases are married and have children.[113][114] One god, Baldr, is said in the myths to have died. Archaeological evidence on the worship of particular gods is sparse, although placenames may also indicate locations where they were venerated. For some gods, particularly Loki,[115][116][117] there is no evidence of worship; however, this may be changed by new archaeological discoveries. Regions, communities, and social classes likely varied in the gods they venerated more or at all.[118][119] There are also accounts in sagas of individuals who devoted themselves to a single deity,[120] described as a fulltrúi or vinr (confidant, friend) as seen in Egill Skallagrímsson's reference to his relationship with Odin in his "Sonatorrek", a tenth-century skaldic poem for example.[121] This practice has been interpreted as heathen past influenced by the Christian cult of the saints. Although our literary sources are all relatively late, there are also indications of change over time.

Norse mythological sources, particularly Snorri and "Vǫluspá", differentiate between two groups of deities, the Æsir and the Vanir, who fought a war during which the Vanir broke down the walls of the Æsir's stronghold, Asgard, and eventually made peace utilizing a truce and the exchange of hostages. Some mythographers have suggested that this myth was based on recollection of a conflict in Scandinavia between adherents of different belief systems.[further explanation needed][122][123]

Major deities among the Æsir include Thor (who is often referred to in literary texts as Asa-Thor), Odin and Týr. Very few Vanir are named in the sources: Njǫrðr, his son Freyr, and his daughter Freyja; according to Snorri all of these could be called Vanaguð (Vanir-god), and Freyja also Vanadís (Vanir-dís).[124] The status of Loki within the pantheon is problematic, and according to "Lokasenna" and "Vǫluspá" and Snorri's explanation, he is imprisoned beneath the earth until Ragnarok, when he will fight against the gods. As far back as 1889 Sophus Bugge suggested this was the inspiration for the myth of Lucifer.[125]

Some of the goddesses—Skaði, Rindr, Gerðr are jötnar origins.

The general Old Norse word for the goddesses is Ásynjur, which is properly the feminine of Æsir. An old word for goddess may be dís, which is preserved as the name of a group of female supernatural beings.[126]

Localised and ancestral deities

editAncestral deities were common among Finno-Ugric peoples and remained a strong presence among the Finns and Sámi after Christianisation.[127] Ancestor veneration may have played a part in the private religious practices of Norse people in their farmsteads and villages;[128][129] in the 10th century, Norwegian pagans attempted to encourage the Christian king Haakon to take part in an offering to the gods by inviting him to drink a toast to the ancestors alongside several named deities.[128]

Þorgerðr Hölgabrúðr and Irpa appear to have been personal or family goddesses venerated by Haakon Sigurdsson, a late pagan ruler of Norway.[130]

There are also likely to have been local and family fertility cults; there is one reported example from pagan Norway in the family cult of Vǫlsi, where a deity called Mǫrnir is invoked.[131][132]

Other beings

editThe Norns are female figures who determine individuals' fate. Snorri describes them as a group of three, but he and other sources also allude to larger groups of Norns who decide the fate of newborns.[133] It is uncertain whether they were worshipped.[134] The landvættir, spirits of the land, were thought to inhabit certain rocks, waterfalls, mountains, and trees, and offerings were made to them.[135] For many, they may have been more important in daily life than the gods.[136] Texts also mention various kinds of elves and dwarfs. Fylgjur, guardian spirits, generally female, were associated with individuals and families. Hamingjur, dísir and swanmaidens are female supernatural figures of uncertain stature within the belief system; the dísir may have functioned as tutelary goddesses.[137] Valkyries were associated with the myths concerning Odin, and also occur in heroic poetry such as the Helgi lays, where they are depicted as princesses who assist and marry heroes.[138][139]

Conflict with the jötnar and gýgjar (often glossed as giants and giantesses respectively) is a frequent motif in the mythology.[140] They are described as both the ancestors and enemies of the gods.[141] Gods marry gýgjar but jötnar's attempts to couple with goddesses are repulsed.[142] Most scholars believe the jötnar were not worshipped, although this has been questioned.[143] The Eddic jötnar have parallels with their later folkloric counterparts, although unlike them they have much wisdom.[144]

Cosmology

editSeveral accounts of the Old Norse cosmogony, or creation myth, appear in surviving textual sources, but there is no evidence that these were certainly produced in the pre-Christian period.[145] It is possible that they were developed during the encounter with Christianity, as pagans sought to establish a creation myth complex enough to rival that of Christianity;[further explanation needed][146] these accounts could also be the result of Christian missionaries interpreting certain elements and tales found in the Old Norse culture and presenting them to be creation myths and a cosmogony, parallel to that of the Bible, in part to aid the Old Norse in the understanding of the new Christian religion through the use of native elements as a means to facilitate conversion (a common practice employed by missionaries to ease the conversion of people from different cultures across the globe. See Syncretism). According to the account in Völuspá, the universe was initially a void known as Ginnungagap. There then appeared a jötunn, Ymir, and after him the gods, who lifted the earth out of the sea.[147] A different account is provided in Vafþrúðnismál, which describes that the world is made from the components of Ymir's body: the earth from his flesh, the mountains from his bones, the sky from his skull, and the sea from his blood.[147] Grímnismál also describes the world being fashioned from Ymir's corpse, although adds the detail that the jötnar emerged from a spring known as Élivágar.[148]

In Snorri's Gylfaginning, it is again stated that the Old Norse cosmogony began with a belief in Ginnungagap, the void. From this emerged two realms, the icy, misty Niflheim and the fire-filled Muspell, the latter ruled over by fire-jötunn, Surtr.[149] A river produced by these realms coagulated to form Ymir, while a cow known as Audumbla then appeared to provide him with milk.[150] Audumbla licked a block of ice to free Buri, whose son Bor married a gýgr named Bestla.[146] Some of the features of this myth, such as the cow Audumbla, are of unclear provenance; Snorri does not specify where he obtained these details as he did for other parts of the myths, and it may be that these were his inventions.[146]

Völuspá portrays Yggdrasil as a giant ash tree.[151] Grímnismál claims that the deities meet beneath Yggdrasil daily to pass judgement.[152] It also claims that a serpent gnaws at its roots while a deer grazes from its higher branches; a squirrel runs between the two animals, exchanging messages.[152] Grímnismál also claims that Yggdrasil has three roots; under one resides the goddess Hel, under another the frost-þursar, and under the third humanity.[152] Snorri also relates that Hel and the frost-þursar live under two of the roots but places the gods, rather than humanity, under the third root.[152] The term Yggr means "the terrifier" and is a synonym for Oðinn, while drasill was a poetic word for a horse; "Yggdrasil" thereby means "Oðinn's Steed".[153] This idea of a cosmic tree has parallels with those from various other societies, and may reflect part of a common Indo-European heritage.[154]

The Ragnarok story survives in its fullest exposition in Völuspá, although elements can also be seen in earlier poetry.[155] The Ragnarok story suggests that the idea of an inescapable fate pervaded Norse worldviews.[156] There is much evidence that Völuspá was influenced by Christian belief,[157] and it is also possible that the theme of conflict being followed by a better future—as reflected in the Ragnarok story—perhaps reflected the period of conflict between paganism and Christianity.[158]

Afterlife

editOld Nordic religion had several fully developed ideas about death and the afterlife.[159] Snorri refers to multiple realms which welcome the dead;[160] although his descriptions reflect a likely Christian influence, the idea of a plurality of other worlds is likely pre-Christian.[161] Unlike Christianity, Old Norse religion does not appear to have adhered to the belief that moral concerns impacted an individual's afterlife destination.[162]

Warriors who died in battle became the Einherjar and were taken to Oðinn's hall, Valhalla. There they waited until Ragnarok when they would fight alongside the Æsir.[163] According to the poem Grímnismál, Valhalla had 540 doors and a wolf stood outside its western door, while an eagle flew overhead.[164] In that poem, it is also claimed that a boar named Sæhrímnir is eaten every day and that a goat named Heiðrún stands atop the hall's roof producing an endless supply of mead.[164] It is unclear how widespread a belief in Valhalla was in Norse society; it may have been a literary creation designed to meet the ruling class' aspirations since the idea of deceased warriors owing military service to Oðinn parallels the social structure between warriors and their lord.[165] There is no archaeological evidence clearly alluding to a belief in Valhalla.[166]

According to Snorri, while one-half of the slain go to Valhalla, the others go to Frejya's hall, Fólkvangr, and those who die from disease or old age go to a realm known as Hel;[167] it was here that Baldr went after his death.[160] The concept of Hel as an afterlife location never appears in pagan-era skaldic poetry, where "Hel" always references the eponymous goddess.[168] Snorri also mentions the possibility of the dead reaching the hall of Brimir in Gimlé, or the hall of Sindri in the Niðafjöll Mountains.[169]

Various sagas and the Eddic poem Helgakviða Hundingsbana II refer to the dead residing in their graves, where they remain conscious.[170] In these thirteenth century sources, ghosts (Draugr) are capable of haunting the living.[171] In both Laxdæla Saga and Eyrbyggja Saga, connections are drawn between pagan burials and hauntings.[172]

In mythological accounts, the deity most closely associated with death is Oðinn. In particular, he is connected with death by hanging; this is apparent in Hávamál, a poem found in the Poetic Edda.[173] In stanza 138 of Hávamál, Oðinn describes his self-sacrifice, in which he hangs himself on Yggdrasill, the world tree, for nine nights, to attain wisdom and magical powers.[174] In the late Gautreks Saga, King Víkarr is hanged and then punctured by a spear; his executioner says "Now I give you to Oðinn".[174]

Cultic practice

editTextual accounts suggest a spectrum of rituals, from large public events to more frequent private and family rites, which would have been interwoven with daily life.[175][176] However, written sources are vague about Norse rituals, and many are invisible to us now even with the assistance of archaeology.[177][178] Sources mention some rituals addressed to particular deities, but the understanding of the relationship between Old Norse ritual and myth remains speculative.[179]

Religious rituals

editSacrifice

editThe primary religious ritual in Norse religion appears to have been sacrifice, or blót.[180] Many texts, both Old Norse and others refer to sacrifices. The Saga of Hákon the Good in Heimskringla states that there were obligatory blóts, at which animals were slaughtered and their blood, called hlaut, sprinkled on the altars and the inside and outside walls of the temple, and ritual toasts were drunk during the ensuing sacrificial feast; the cups were passed over the fire and they and the food were consecrated with a ritual gesture by the chieftain; King Hákon, a Christian, was forced to participate but made the sign of the cross.[181] The description of the temple at Uppsala in Adam of Bremen's History includes an account of a festival every nine years at which nine males of every kind of animal were sacrificed and the bodies hung in the temple grove.[182] There may have been many methods of sacrifice: several textual accounts refer to the body or head of the slaughtered animal being hung on a pole or tree.[183] In addition to seasonal festivals, an animal blót could take place, for example, before duels, after the conclusion of business between traders, before sailing to ensure favourable winds, and at funerals.[184] Remains of animals from many species have been found in graves from the Old Norse period,[185][186] and Ibn Fadlan's account of a ship burial includes the sacrifice of a dog, draft animals, cows, a rooster and a hen as well as that of a servant girl.[187]

In the Eddic poem "Hyndluljóð", Freyja expresses appreciation for the many sacrifices of oxen made to her by her acolyte, Óttar.[188] In Hrafnkels saga, Hrafnkell is called Freysgoði for his many sacrifices to Freyr.[189][64] There may also be markers by which we can distinguish sacrifices to Odin,[190] who was associated with hanging,[191] and some texts particularly associate the ritual killing of a boar with sacrifices to Freyr;[191] but in general, archaeology is unable to identify the deity to whom a sacrifice was made.[190]

The texts frequently allude to human sacrifice. Temple wells in which people were sacrificially drowned are mentioned in Adam of Bremen's account of Uppsala[192] and in Icelandic sagas, where they are called blótkelda or blótgrǫf,[193] and Adam of Bremen also states that human victims were included among those hanging in the trees at Uppsala.[194] In Gautreks saga, people sacrifice themselves during a famine by jumping off cliffs,[195] and both the Historia Norwegiæ and Heimskringla refer to the willing death of King Dómaldi as a sacrifice after bad harvests.[196] Mentions of people being "sentenced to sacrifice" and of the "wrath of the gods" against criminals suggest a sacral meaning for the death penalty;[197] in Landnamabók the method of execution is given as having the back broken on a rock.[195] It is possible that some of the bog bodies recovered from peat bogs in northern Germany and Denmark and dated to the Iron Age were human sacrifices.[198] Such a practice may have been connected to the execution of criminals or of prisoners of war,[199] and Tacitus also states that such type of execution was used as a punishment for "the coward, the unwarlike and the man stained with abominable vices" for the reason that these were considered "infamies that ought to be buried out of sight";[f] on the other hand, some textual mentions of a person being "offered" to a deity, such as a king offering his son, may refer to a non-sacrificial "dedication".[200]

Archaeological evidence supports Ibn Fadlan's report of funerary human sacrifice: in various cases, the burial of someone who died of natural causes is accompanied by another who died a violent death.[190][201] For example, at Birka a decapitated young man was placed atop an older man buried with weapons, and at Gerdrup, near Roskilde, a woman was buried alongside a man whose neck had been broken.[202] Many of the details of Ibn Fadlan's account are born out by archaeology;[203][204][115] and it is possible that those elements which are not visible in the archaeological evidence—such as the sexual encounters—are also accurate.[204]

Deposition

editDeposition of artefacts in wetlands was a practice in Scandinavia during many periods of prehistory.[205][206][207] In the early centuries of the Common Era, huge numbers of destroyed weapons were placed in wetlands: mostly spears and swords, but also shields, tools, and other equipment. Beginning in the 5th century, the nature of the wetland deposits changed; in Scandinavia, fibulae and bracteates were placed in or beside wetlands from the 5th to the mid-6th centuries, and again beginning in the late 8th century,[208] when weapons, as well as jewellery, coins and tools, again began to be deposited, the practice lasting until the early 11th century.[208] This practice extended to non-Scandinavian areas inhabited by Norse people; for example in Britain, a sword, tools, and the bones of cattle, horses and dogs were deposited under a jetty or bridge over the River Hull.[209] The precise purposes of such depositions are unclear.[citation needed]

It is harder to find ritualised deposits on dry land. However, at Lunda (meaning "grove") near Strängnäs in Södermanland, archaeological evidence has been found at a hill of presumably ritual activity from the 2nd century BCE until the 10th century CE, including deposition of unburnt beads, knives and arrowheads from the 7th to the 9th century.[210][207] Also during excavations at the church in Frösö, bones of bear, elk, red deer, pigs, cattle, and either sheep or goats were found surrounding a birch tree, having been deposited in the 9th or 10th century; the tree likely had sacrificial associations and perhaps represented Yggdrasill.[210][211]

Rites of passage

editA child was accepted into the family via a ritual of sprinkling with water (Old Norse ausa vatni) which is mentioned in two Eddic poems, "Rígsþula" and "Hávamál", and was afterwards given a name.[212] The child was frequently named after a dead relative, since there was a traditional belief in rebirth, particularly in the family.[213]

Old Norse sources also describe rituals for adoption (the Norwegian Gulaþing Law directs the adoptive father, followed by the adoptive child, then all other relatives, to step in turn into a specially made leather shoe) and blood brotherhood (a ritual standing on the bare earth under a specially cut strip of grass, called a jarðarmen).[214]

Weddings occur in Icelandic family sagas. The Old Norse word brúðhlaup has cognates in many other Germanic languages and means "bride run"; it has been suggested that this indicates a tradition of bride-stealing, but other scholars including Jan de Vries interpreted it as indicating a rite of passage conveying the bride from her birth family to that of her new husband.[215] The bride wore a linen veil or headdress; this is mentioned in the Eddic poem "Rígsþula".[216] Freyr and Thor are each associated with weddings in some literary sources.[217] In Adam of Bremen's account of the pagan temple at Uppsala, offerings are said to be made to Fricco (presumably Freyr) on the occasion of marriages,[182] and in the Eddic poem "Þrymskviða", Thor recovers his hammer when it is laid in his disguised lap in a ritual consecration of the marriage.[218][219] "Þrymskviða" also mentions the goddess Vár as consecrating marriages; Snorri Sturluson states in Gylfaginning that she hears the vows men and women make to each other, but her name probably means "beloved" rather than being etymologically connected to Old Norse várar, "vows".[220]

Burial of the dead is the Norse rite of passage about which we have most archaeological evidence.[221] There is considerable variation in burial practices, both spatially and chronologically, which suggests a lack of dogma about funerary rites.[221][222] Both cremations and inhumations are found throughout Scandinavia,[221][223] but in Viking Age Iceland there were inhumations but, with one possible exception, no cremations.[223] The dead are found buried in pits, wooden coffins or chambers, boats, or stone cists; cremated remains have been found next to the funeral pyre, buried in a pit, in a pot or keg, and scattered across the ground.[221] Most burials have been found in cemeteries, but solitary graves are not unknown.[221] Some grave sites were left unmarked, others memorialised with standing stones or burial mounds.[221]

Grave goods feature in both inhumation and cremation burials.[224] These often consist of animal remains; for instance, in Icelandic pagan graves, the remains of dogs and horses are the most common grave goods.[225] In many cases, the grave goods and other features of the grave reflect social stratification, particularly in the cemeteries at market towns such as Hedeby and Kaupang.[224] In other cases, such as in Iceland, cemeteries show very little evidence of it.[223]

Ship burial is a form of elite inhumation attested both in the archaeological record and in Ibn Fadlan's written account. Excavated examples include the Oseberg ship burial near Tønsberg in Norway, another at Klinta on Öland,[226] and the Sutton Hoo ship burial in England.[227] A boat burial at Kaupang in Norway contained a man, woman, and baby lying adjacent to each other alongside the remains of a horse and dismembered dog. The body of a second woman in the stern was adorned with weapons, jewellery, a bronze cauldron, and a metal staff; archaeologists have suggested that she may have been a sorceress.[226] In certain areas of the Nordic world, namely coastal Norway and the Atlantic colonies, smaller boat burials are sufficiently common to indicate it was no longer only an elite custom.[227]

Ship burial is also mentioned twice in the Old Norse literary-mythic corpus. A passage in Snorri Sturluson's Ynglinga Saga states that Odin—whom he presents as a human king later mistaken for a deity—instituted laws that the dead would be burned on a pyre with their possessions, and burial mounds or memorial stones erected for the most notable men.[228][229] Also in his Prose Edda, the god Baldr is burned on a pyre on his ship, Hringhorni, which is launched out to sea with the aid of the gýgr Hyrrokkin; Snorri wrote after the Christianisation of Iceland, but drew on Úlfr Uggason's skaldic poem "Húsdrápa".[230]

Mysticism, magic, animism and shamanism

editThe myth preserved in the Eddic poem "Hávamál" of Odin hanging for nine nights on Yggdrasill, sacrificing himself to secure knowledge of the runes and other wisdom in what resembles an initiatory rite,[231][232] is evidence of mysticism in Old Norse religion.[233]

The gods were associated with two distinct forms of magic. In "Hávamál" and elsewhere, Odin is particularly associated with the runes and with galdr.[234][235] Charms, often associated with the runes, were a central part of the treatment of disease in both humans and livestock in Old Norse society.[236] In contrast seiðr and the related spæ, which could involve both magic and divination,[237] were practised mostly by women, known as vǫlur and spæ-wives, often in a communal gathering at a client's request.[237] 9th- and 10th-century female graves containing iron staffs and grave goods have been identified on this basis as those of seiðr practitioners.[238] Seiðr was associated with the Vanic goddess Freyja; according to a euhemerized account in Ynglinga saga, she taught seiðr to the Æsir,[239] but it involved so much ergi ("unmanliness, effeminacy") that other than Odin himself, its use was reserved for priestesses.[240][241][242] There are, however, mentions of male seiðr workers, including elsewhere in Heimskringla, where they are condemned for their perversion.[243]

In Old Norse literature, practitioners of seiðr are sometimes described as foreigners, particularly Sami or Finns or in rarer cases from the British Isles.[244] Practitioners such as Þorbjörg Lítilvölva in the Saga of Erik the Red appealed to spirit helpers for assistance.[237] Many scholars have pointed to this and other similarities between what is reported of seiðr and spæ ceremonies and shamanism.[245] The historian of religion Dag Strömbäck regarded it as a borrowing from Sami or Balto-Finnic shamanic traditions,[246][247] but there are also differences from the recorded practices of Sami noaidi.[248] Since the 19th century, some scholars have sought to interpret other aspects of Old Norse religion itself by comparison with shamanism;[249] for example, Odin's self-sacrifice on the World Tree has been compared to Finno-Ugric shamanic practices.[250] However, the scholar Jan de Vries regarded seiðr as an indigenous shamanic development among the Norse,[251][252] and the applicability of shamanism as a framework for interpreting Old Norse practices, even seiðr, is disputed by some scholars.[199][253]

Religious sites

editOutdoor rites

editReligious practices often took place outdoors. For example, at Hove in Trøndelag, Norway, offerings were placed at a row of posts bearing images of gods.[254] Terms particularly associated with outdoor worship are vé (shrine) and hörgr (cairn or stone altar). Many place names contain these elements in association with the name of a deity, and for example at Lilla Ullevi (compounded with the name of the god Ullr) in Bro parish, Uppland, Sweden, archaeologists have found a stone-covered ritual area at which offerings including silver objects, rings, and a meat fork had been deposited.[255] Place-name evidence suggests that cultic practices might also take place at many different kinds of sites, including fields and meadows (vangr, vin), rivers, lakes and bogs, groves (lundr) and individual trees, and rocks.[176][256]

Some Icelandic sagas mention sacred places. In both Landnámabók and Eyrbyggja saga, members of a family who particularly worshipped Thor are said to have passed after death into the mountain Helgafell (holy mountain), which was not to be defiled by bloodshed or excrement or even to be looked at without washing first.[257][258] Mountain worship is also mentioned in Landnámabók as an old Norwegian tradition to which Auðr the Deepminded's family reverted after she died; the scholar Hilda Ellis Davidson regarded it as associated particularly with the worship of Thor.[257][259] In Víga-Glúms saga, the field Vitazgjafi (certain giver) is associated with Freyr and similarly not to be defiled.[260][261] The scholar Stefan Brink has argued that one can speak of a "mythical and sacral geography" in pre-Christian Scandinavia.[262]

Temples

editSeveral of the sagas refer to cult houses or temples, generally called in Old Norse by the term hof. There are detailed descriptions of large temples, including a separate area with images of gods and the sprinkling of sacrificial blood using twigs like the Christian use of the aspergillum, in Kjalnesinga saga and Eyrbyggja saga; Snorri's description of blót in Heimskringla adds more details about the blood sprinkling.[263] Adam of Bremen's 11th-century Latin history describes at length a great temple at Uppsala at which human sacrifices regularly took place, and containing statues of Thor, Wotan and Frikko (presumably Freyr); a scholion adds the detail that a golden chain hung from the eaves.[264][265]

These details appear exaggerated and probably indebted to Christian churches, and in the case of Uppsala to the Biblical description of Solomon's temple.[263][264][265] Based on the dearth of archaeological evidence for dedicated cult houses, particularly under early church buildings in Scandinavia, where they were expected to be found, and additionally on Tacitus' statement in Germania that the Germanic tribes did not confine their deities to buildings,[266] many scholars have believed hofs to be largely a Christian idea of pre-Christian practice. In 1966, based on the results of a comprehensive archaeological survey of most of Scandinavia, the Danish archaeologist Olaf Olsen proposed the model of the "temple farm": that rather than the hof being a dedicated building, a large longhouse, especially that of the most prominent farmer in the district, served as the location for community cultic celebrations when required.[267][268]

Since Olsen's survey, however, archaeological evidence of temple buildings has come to light in Scandinavia. Although Sune Lindqvist's interpretation of post holes which he found under the church at Gamla Uppsala as the remains of an almost square building with a high roof was wishful thinking,[269] excavations nearby in the 1990s uncovered both a settlement and a long building which may have been either a longhouse used seasonally as a cult house or a dedicated hof.[270] The building site at Hofstaðir, near Mývatn in Iceland, which was a particular focus of Olsen's work, has since been re-excavated and the layout of the building and further discoveries of the remains of ritually slaughtered animals now suggest that it was a cult house until ritually abandoned.[271] Other buildings that have been interpreted as cult houses have been found at Borg in Östergötland, Lunda in Södermanland,[180] and Uppakra in Scania,[272][273] Remains of one pagan temple have so far been found under a medieval church, at Mære in Nord-Trøndelag, Norway.[254][274]

In Norway, the word hof appears to have replaced older terms referring to outdoor cult sites during the Viking Age;[275] it has been suggested that the use of cult buildings was introduced into Scandinavia starting in the 3rd century based on the Christian churches then proliferating in the Roman Empire, as part of a range of political and religious changes that Nordic society was then experiencing.[238] Some of the cult houses which have been found are located within what archaeologists call "central places": settlements with various religious, political, judicial, and mercantile functions.[276][272] A number of these central places have place-names with cultic associations, such as Gudme (home of gods), Vä (vé), and Helgö (holy island).[272] Some archaeologists have argued that they were designed to mirror Old Norse cosmology, thus connecting ritual practices with wider worldviews.[272][277]

Priests and kings

editThere is no evidence of a professional priesthood among the Norse, and rather cultic activities were carried out by members of the community who also had other social functions and positions.[278] In Old Norse society, religious authority was harnessed to secular authority; there was no separation between economic, political, and symbolic institutions.[279] Both the Norwegian kings' sagas and Adam of Bremen's account claim that kings and chieftains played a prominent role in cultic sacrifices.[278] In medieval Iceland, the goði was a social role that combined religious, political, and judicial functions,[278] responsible for serving as a chieftain in the district, negotiating legal disputes, and maintaining order among his þingmenn.[280] Most evidence suggests that public cultic activity was largely the preserve of high-status males in Old Norse society.[281] However, there are exceptions. The Landnámabók refers to two women holding the position of gyðja, both of whom were members of local chiefly families.[280] In Ibn Fadlan's account of the Rus, he describes an elder woman known as the "Angel of Death" who oversaw a funerary ritual.[226]

Among scholars, there has been much debate as to whether sacral kingship was practised among Old Norse communities, in which the monarch was endowed with a divine status and thus responsible for ensuring that a community's needs were met through supernatural means.[282] Evidence for this has been cited from the Ynglingatal poem in which the Swedes kill their king, Domalde, following a famine.[283] However, interpretations of this event other than sacral kingship are possible; for instance, Domalde may have been killed in a political coup.[283]

Iconography and imagery

editThe most widespread religious symbol in the Viking Age Old Norse religion was Mjöllnir, the hammer of Thor.[284] This symbol first appears in the ninth century and might be a conscious response to the symbolism of the Christian cross.[28] Although found across the Viking world, Mjöllnir pendants are most commonly found in graves from modern Denmark, south-eastern Sweden, and southern Norway; their wide distribution suggests the particular popularity of Thor.[285] When found in inhumation graves, Mjöllnir pendants are more likely to be found in women's graves than men's.[286] Earlier examples were made from iron, bronze, or amber,[284] although silver pendants became fashionable in the tenth century.[284] This may have been a response to the growing popularity of Christian cross amulets.[287]

The two religious symbols may have co-existed closely; one piece of archaeological evidence suggesting that this is the case is a soapstone mould for casting pendants discovered from Trengården in Denmark. This mould had space for a Mjöllnir and a crucifix pendant side by side, suggesting that the artisan who produced these pendants catered for both religious communities.[288] These have typically been interpreted as a protective symbol, although may also have had associations with fertility, being worn as amulets, good-luck charms, or sources of protection.[289] However, around 10 per cent of those discovered during excavation had been placed on top of cremation urns, suggesting that they had a place in certain funerary rituals.[286]

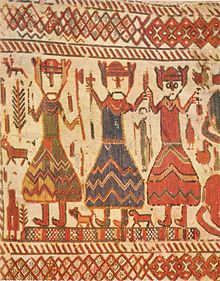

Gods and goddesses were depicted through figurines, pendants, fibulas, and as images on weapons.[290] Thor is usually recognised in depictions by his carrying of Mjöllnir.[290] Iconographic material suggesting other deities are less common than those connected to Thor.[286] Some pictorial evidence, most notably that of the picture stones, intersects with the mythologies recorded in later texts.[159] These picture stones, produced in mainland Scandinavia during the Viking Age, are the earliest known visual depictions of Norse mythological scenes.[30] It is nevertheless unclear what function these picture-stones had or what they meant to the communities who produced them.[30]

Oðinn has been identified on various gold bracteates produced from the fifth and sixth centuries.[290] Some figurines have been interpreted as depictions of deities. The Lindby image from Skåne, Sweden is often interpreted as Oðinn because of its missing eye;[291] the bronze figurine from Eyrarland in Iceland as Thor because it holds a hammer.[292] A bronze figurine from Rällinge in Södermanland has been attributed to Freyr because it has a big phallus, and a silver pendant from Aska in Östergötland has been seen as Freya because it wears a necklace that could be Brisingamen.[290]

Another image that recurs in Norse artwork from this period is the valknut (the term is modern, not Old Norse).[293] These symbols may have a specific association with Oðinn, because they often accompany images of warriors on picture stones.[294]

Influence

editRomanticism, aesthetics, and politics

editDuring the romanticist movement of the 19th century, various northern Europeans took an increasing interest in Old Norse religion, seeing in it ancient pre-Christian mythology that provided an alternative to the dominant Classical mythology. As a result, artists featured Norse gods and goddesses in their paintings and sculptures, and their names were applied to streets, squares, journals, and companies throughout parts of northern Europe.[295]

The mythological stories derived from Old Norse and other Germanic sources inspired various artists, including Richard Wagner, who used these narratives as the basis for his Der Ring des Nibelungen.[295] Also inspired by these Old Norse and Germanic tales was J. R. R. Tolkien, who used them in creating his legendarium, the fictional universe in which he set novels like The Lord of the Rings.[295] During the 1930s and 1940s, elements of Old Norse and other Germanic religions were adopted by Nazi Germany.[295] Since the fall of the Nazis, various right-wing groups continue to use elements of Old Norse and Germanic religion in their symbols, names, and references;[295] some Neo-Nazi groups, for instance, use Mjöllnir as a symbol.[296]

Theories about a shamanic component of Old Norse religion have been adopted by forms of Nordic neoshamanism; groups practising what they called seiðr was established in Europe and the United States by the 1990s.[297]

Scholarly study

editResearch into Old Norse religion has been interdisciplinary, involving historians, archaeologists, philologists, place-name scholars, literary scholars, and historians of religion.[295] Scholars from different disciplines have tended to take different approaches to the material; for instance, many literary scholars have been highly sceptical about how accurately Old Norse text portrays pre-Christian religion, whereas historians of religion have tended to regard these portrayals as highly accurate.[298]

Interest in Norse mythology was revived in the eighteenth century,[299] and scholars turned their attention to it in the early 19th century.[295] Since this research appeared from the background of European romanticism, many of the scholars operating in the 19th and 20th centuries framed their approach through nationalism, and were strongly influenced by their interpretations by romantic notions about nationhood, conquest, and religion.[300] Their understanding of cultural interaction was also coloured by 19th-century European colonialism and imperialism.[301] Many regarded pre-Christian religion as singular and unchanging, directly equated religion with the nation, and projected modern national borders onto the Viking Age past.[301]

Due to the use of Old Norse and Germanic iconography by the Nazis, academic research into Old Norse religion reduced heavily following the Second World War.[295] Scholarly interest in the subject then revived in the late 20th century.[295] By the 21st century, Old Norse religion was regarded as one of the best known non-Christian religions from Europe, alongside that of Greece and Rome.[302]

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ "As religions and languages often spread at different speeds and cover different areas, the question of the ancientness of religious structures and essential elements of the North Germanic religion is treated separately from the question of language age" (Walter de Gruyter 2002:390)

- ^ "The dying god of North Germanic religion is Baldr, that of the Phoenicians is Ba'al" (Vennemann 2012:390)

- ^ "Kuhn's arguments go back at least to his essay on North Germanic paganism in the early Christian era" (Niles & Amodio 1989:25)

- ^ "Genuine sources sources from the time of North Germanic paganism (runic inscriptions, ancient poetry etc.)" (Lönnroth 1965:25)

- ^ In addition to the verses cited in the Prose Edda, which are for the most part close to one of the two. Dronke, The Poetic Edda, Volume 2: Mythological Poems, Oxford: Oxford University, 1997, repr. 2001, ISBN 978-0-19-811181-8, pp. 61–62, 68–79.

- ^ "Traitors and deserters are hanged on trees; the coward, the unwarlike, the man stained with abominable vices, is plunged into the mire of the morass, with a hurdle put over him. This distinction in punishment means that crime, they think, ought, in being punished, to be exposed, while infamy ought to be buried out of sight." (Germania, chapter XII)

References

edit- ^ Andrén 2011, p. 846; Andrén 2014, p. 14.

- ^ Nordland 1969, p. 66; Turville-Petre 1975, p. 3; Näsström 1999, p. 12; Näsström 2003, p. 1; Hedeager 2011, p. 104; Jennbert 2011, p. 12.

- ^ Andrén 2005, p. 106; Andrén, Jennbert & Raudvere 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 1; Steinsland 1986, p. 212.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 16.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 8.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 52; Jesch 2004, p. 55; O'Donoghue 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Simpson 1967, p. 190.

- ^ Clunies Ross 1994, p. 41; Hultgård 2008, p. 212.

- ^ a b Andrén 2011, p. 856.

- ^ Davidson 1990, p. 14.

- ^ a b Andrén 2011, p. 846.

- ^ a b Hultgård 2008, p. 212.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 42.

- ^ a b Andrén, Jennbert & Raudvere 2006, p. 12.

- ^ Andrén, Jennbert & Raudvere 2006, p. 12; Andrén 2011, p. 853.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 105.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 41; Brink 2001, p. 88.

- ^ Davidson 1990, p. 14: DuBois 1999, pp. 44, 206; Andrén, Jennbert & Raudvere 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Andrén 2014, p. 16.

- ^ a b Andrén, Jennbert & Raudvere 2006, p. 13.

- ^ Bek-Pedersen 2011, p. 10.

- ^ Davidson 1990, p. 16.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 18.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 7.

- ^ a b DuBois 1999, p. 10.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 22.

- ^ a b Andrén, Jennbert & Raudvere 2006, p. 14.

- ^ Davidson, Lost Beliefs, pp. 1; Davidson, Gods and Myths, pp. 18.

- ^ a b c Abram 2011, p. 9.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, pp. 82–83.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 11.

- ^ Ursula Dronke, ed. and trans., The Poetic Edda, Volume 3: Mythological Poems II, Oxford: Oxford University, 2011, ISBN 978-0-19-811182-5, p. 63, note to "Hávamál", Verse 144.

- ^ Näsström, "Fragments", p. 12.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 10.

- ^ Davidson, Gods and Myths, p. 15.

- ^ Turville Petre, p. 13.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 24.

- ^ a b Abram 2011, p. 27.

- ^ Davidson, "Human Sacrifice", p. 337.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 28.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Andrén, Religion, p. 846; Cosmology, p. 14.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 8.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 2, 4.

- ^ Andrén, "Behind 'Heathendom'", p. 106.

- ^ a b Turville-Petre 1975, pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Abram 2011, p. 61.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 1, p. 46.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 60.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 1, p. 60.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 5.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 53, 79.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 6.

- ^ Lindow 2002, p. 3.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 54.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 7.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 58.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 54–55.

- ^ DuBois 1999, pp. 20–21.

- ^ Cusack 1998, p. 160; Abram 2011, p. 108.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 108.

- ^ a b Sundqvist, An Arena for Higher Powers, pp. 87–88.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, pp. 60–61; Abram 2011, p. 108.

- ^ Cusack 1998, p. 161; O'Donoghue 2008, p. 64.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 182.

- ^ Cusack 1998, p. 161; O'Donoghue 2008, p. 4; Abram 2011, p. 182.

- ^ Jolly 1996, p. 36; Pluskowski 2011, p. 774.

- ^ Jesch 2011, pp. 19–20.

- ^ Gelling 1961, p. 13; Meaney 1970, p. 120; Jesch 2011, p. 15.

- ^ Meaney 1970, p. 120.

- ^ Jolly 1996, p. 36.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 154.

- ^ a b Cusack 1998, p. 151.

- ^ Jolly 1996, pp. 41–43; Jesch 2004, p. 56.

- ^ Pluskowski 2011, p. 774.

- ^ Cusack 1998, pp. 119–27; DuBois 1999, p. 154.

- ^ Cusack 1998, p. 135.

- ^ Cusack 1998, pp. 135–36.

- ^ Cusack 1998, p. 140.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 99–100.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 123–24.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 128–30.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 141.

- ^ Davidson 1990, p. 12; Cusack 1998, pp. 146–47; Abram 2011, pp. 172–74.

- ^ Lindow 2002, pp. 7, 9.

- ^ Cusack 1998, p. 163; Abram 2011, p. 187.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 188.

- ^ Cusack 1998, pp. 164–68; Abram 2011, pp. 189–90.

- ^ a b Cusack 1998, p. 176.

- ^ Cusack 1998, p. 145; Abram 2011, p. 176.

- ^ Davidson 1990, pp. 219–20; Abram 2011, p. 156.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 171; Andrén 2011, p. 856.

- ^ Cusack 1998, p. 168.

- ^ a b Cusack 1998, p. 179.

- ^ Davidson 1990, p. 23.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 193.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 178.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 201, 208.

- ^ a b Abram 2011, p. 191.

- ^ Jesch 2004, p. 57.

- ^ Jesch 2004, pp. 57–59.

- ^ a b Abram 2011, p. 207.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 208, 219.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, p. 6.

- ^ Schön 2004, pp. 169–179.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 81.

- ^ Turville-Petre, pp. 24–25; p. 79 regarding his changes to the story in "Þórsdrápa" of Thor's journey to the home of the jötunn Geirrǫðr.

- ^ a b O'Donoghue 2008, p. 19.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, p. 8.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 171.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 79, 228.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, pp. 23–24.

- ^ a b O'Donoghue 2008, p. 67.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 151.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 1, p. 265.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 62–63.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 59.

- ^ Davidson, Gods and Myths, p. 219.

- ^ Sundqvist, An Arena for Higher Powers, pp. 87–90.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, p. 27.

- ^ Nordland 1969, p. 67.

- ^ Skáldskaparmál, ch. 14, 15, 29; Edda Snorra Sturlusonar: udgivet efter handskrifterne, ed. Finnur Jónsson, Copenhagen: Gyldendal, 1931, pp. 97–98, 110.

- ^ Anna Birgitta Rooth, Loki in Scandinavian Mythology, Acta Regiae Societatis humaniorum litterarum Lundensis 61, Lund: Gleerup, 1961, OCLC 902409942, pp. 162–65.

- ^ Lotte Motz, "Sister in the Cave; the stature and the function of the female figures of the Eddas", Arkiv för nordisk filologi 95 (1980) 168–82.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 46.

- ^ a b DuBois 1999, p. 47.

- ^ Jónas Gíslason "Acceptance of Christianity in Iceland in the Year 1000 (999)", in: Old Norse and Finnish Religions and Cultic Place-Names, ed. Tore Ahlbäck, Turku: Donner Institute for Research in Religious and Cultural History, 1991, OCLC 474369969, pp. 223–55.

- ^ Simek, "Þorgerðr Hǫlgabrúðr", pp. 326–27.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 2, p. 284.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, pp. 256–57.

- ^ Lindow, "Norns", pp. 244–45.

- ^ De Vries 1970, p. 272.

- ^ Dubois, p. 50

- ^ Davidson, Gods and Myths, p. 214.

- ^ Turville-Petre, p. 221 Archived 23 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Davidson, Gods and Myths, p. 61.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 1, pp. 273–74.

- ^ Simek, "Giants", p. 107.

- ^ Motz, "Giants in Folklore and Mythology: A New Approach", Folklore (1982) 70–84, p. 70.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, p. 232.

- ^ Steinsland 1986, pp. 212–13.

- ^ Motz, "Giants", p. 72.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, p. 116.

- ^ a b c O'Donoghue 2008, p. 16.

- ^ a b O'Donoghue 2008, p. 13.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, p. 14.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, pp. 114–15.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, p. 15.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, pp. 17–18.

- ^ a b c d O'Donoghue 2008, p. 18.

- ^ O'Donoghue 2008, p. 17.

- ^ Hultgård 2008, p. 215.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 157–58.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 163.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 165.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 164.

- ^ a b Abram 2011, p. 4.

- ^ a b DuBois 1999, p. 79.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 81.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 212.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 89.

- ^ a b Abram 2011, p. 107.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 105–06.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 78.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 79Abram 2011, p. 116

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 119.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 80.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 77.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 85.

- ^ DuBois 1999, pp. 87–88.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 75.

- ^ a b Abram 2011, p. 76.

- ^ Andrén, "Old Norse and Germanic Religion", pp. 848–49.

- ^ a b Andrén, "Behind 'Heathendom'", p. 108.

- ^ Jacqueline Simpson, "Some Scandinavian Sacrifices", Folklore 78.3 (1967) 190–202, p. 190.

- ^ Andrén, "Old Norse and Germanic Religion", pp. 853, 855.

- ^ Clunies Ross 1994, p. 13.

- ^ a b Abram 2011, p. 70.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 251.

- ^ a b Turville-Petre 1975, p. 244.

- ^ Simpson 1967, p. 193.

- ^ Magnell 2012, p. 195.

- ^ Magnell 2012, p. 196.

- ^ Davidson, "Human Sacrifice".

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 273.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 239.

- ^ "Hrafnkel's Saga", tr. Hermann Pálsson, in Hrafnkel's Saga and Other Icelandic Stories, Harmondsworth, Middlesex: Penguin, 1985, ISBN 9780140442380, ch. 1 Archived 23 April 2023 at the Wayback Machine: "He loved Frey above all the other gods and gave him a half-share in all his best treasures. ... He became their priest and chieftain, so he was given the nickname Frey's-Priest."

- ^ a b c Abram 2011, p. 71.

- ^ a b Turville-Petre 1975, p. 255.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, pp. 245–46.

- ^ Kjalnesinga saga, Vatnsdæla saga; De Vries Volume 1, p. 410, Turville-Petre, p. 254.

- ^ Davidson, "Human Sacrifice", p. 337.

- ^ a b Turville-Petre 1975, p. 254.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 253.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 1, p. 414.

- ^ Davidson, "Human Sacrifice", p. 333.

- ^ a b Andrén, "Old Norse and Germanic Religion", p. 849.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 1, p. 415.

- ^ Davidson, "Human Sacrifice", p. 334.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 72.

- ^ Ellis Davidson, "Human Sacrifice", p. 336.

- ^ a b Abram 2011, p. 73.

- ^ Brink 2001, p. 96.

- ^ Andrén, "Behind 'Heathendom'", pp. 108–09.

- ^ a b Andrén, "Old Norse and Germanic Religion", p. 853.

- ^ a b Julie Lund, (2010). "At the Water's Edge", in Martin Carver, Alex Sanmark, and Sarah Semple, eds., Signals of Belief in Early England: Anglo-Saxon Paganism Revisited, ISBN 978-1-84217-395-4, Oxford: Oxbow, pp. 49–66. p. 51.

- ^ Hutton 2013, p. 328.

- ^ a b Andrén, "Behind 'Heathendom'", p. 110.

- ^ Andrén, "Old Norse and Germanic Religion", pp. 853–54.

- ^ De Vries, Volume 1, pp. 178–80. Before the water rite, a child could be rejected; infanticide was still permitted under the earliest Christian laws of Norway, p. 179.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 1, pp. 181–83.

- ^ De Vries, Volume 1, pp. 184, 208, 294–95; De Vries suggests the jarðarmen ritual is a symbolic death and rebirth.

- ^ De Vries, Volume 1, pp. 185–86. Brúðkaup, "bride-purchase", also occurs in Old Norse, but according to de Vries probably refers to the bride price and hence to gift-giving rather than "purchase" in the modern sense.

- ^ gekk hón und líni; De Vries, Volume 1, p. 187.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 1, p. 187.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 81.

- ^ Margaret Clunies Ross, "Reading Þrymskviða", in The Poetic Edda: Essays on Old Norse Mythology, ed. Paul Acker and Carolyne Larrington, Routledge medieval casebooks, New York / London: Routledge, 2002, ISBN 9780815316602, pp. 177–94, p. 181.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 2, p. 327.

- ^ a b c d e f Andrén, "Old Norse and Germanic Religion", p. 855.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 71.

- ^ a b c Rúnar Leifsson, (2012). "Evolving Traditions: Horse Slaughter as Part of Viking Burial Customs in Iceland", in The Ritual Killing and Burial of Animals: European Perspectives, ed. Aleksander Pluskowski, Oxford: Oxbow, 2012, ISBN 978-1-84217-444-9, pp. 184–94, p. 185.

- ^ a b DuBois 1999, p. 72.

- ^ Rúnar Leifsson, p. 184.

- ^ a b c Abram 2011, p. 74.

- ^ a b DuBois 1999, p. 73.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 80.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Gylfaginning, ch. 48; Simek, "Hringhorni", pp. 159–60; "Hyrrokkin", p. 170.

- ^ Davidson, Gods and Myths, pp. 143–44.

- ^ Simek, "Odin's (self-)sacrifice", p. 249.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, pp. 11, 48–50.

- ^ Simek, "Runes", p. 269: "Odin is the god of runic knowledge and of runic magic."

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, pp. 64–65.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 104.

- ^ a b c DuBois 1999, p. 123.

- ^ a b Andrén, "Old Norse and Germanic Religion", p. 855.

- ^ Davidson, Gods and Myths, p. 117.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 65.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 136.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 1, p. 332.

- ^ Davidson, Gods and Myths, p. 121.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 128.

- ^ Davidson, "Gods and Myths", p. 119.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 129.

- ^ Schnurbein 2003, pp. 117–18.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 130.

- ^ Schnurbein 2003, p. 117.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 50.

- ^ Schnurbein 2003, p. 119.

- ^ De Vries 1970, Volume 1, pp. 330–33.

- ^ Schnurbein 2003, p. 123.

- ^ a b Berend 2007, p. 124.

- ^ Sundqvist, An Arena for Higher Powers, pp. 131, 394.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, pp. 237–38.

- ^ a b DuBois 1999, p. 76.

- ^ Brink 2001, p. 100.

- ^ Ellis, Road to Hel, p. 90.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, pp. 69, 165–66.

- ^ Ellis Davidson, Gods and Myths, pp. 101–02.

- ^ Brink 2001, p. 77.

- ^ a b De Vries 1970, Volume 1, pp. 382, 389, 409–10.

- ^ a b Turville-Petre 1975, pp. 244–45.

- ^ a b Simek, "Uppsala temple", pp. 341–42.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 69.

- ^ Olsen, English summary p. 285: "[I] suggest that the building of the pagan hof in Iceland was, in fact, identical with the veizluskáli [feasthall] of the large farm: a building in everyday use which on special occasions became the setting for the ritual gatherings of a large number of people."

- ^ Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe, p. 32: "the hall of a farmhouse used for communal religious feasts, perhaps that of the goði or leading man of the district who would preside over such gatherings."

- ^ Olsen 1966, pp. 127–42; English summary is at Olsen 1966, pp. 282–83.

- ^ Richard Bradley, Ritual and Domestic Life in Prehistoric Europe, London/New York: Routledge, 2005, ISBN 0-415-34550-2, pp. 43–44, citing Neil S. Price, The Viking Way: Religion and War in Late Iron Age Scandinavia, Doctoral thesis, Aun 31, Uppsala: Department of Archaeology and Ancient History, 2002, ISBN 9789150616262, p. 61.

- ^ Lucas & McGovern 2007, pp. 7–30.

- ^ a b c d Andrén, "Old Norse and Germanic Religion", p. 854.

- ^ Magnell 2012, p. 199.

- ^ Davidson, Myths and Symbols in Pagan Europe, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Turville-Petre 1975, p. 243.

- ^ Hedeager, "Scandinavian 'Central Places'", p. 7.

- ^ Hedeager, "Scandinavian 'Central Places'", pp. 5, 11–12.

- ^ a b c Hultgård 2008, p. 217.

- ^ Hedeager 2002, p. 5 Abram 2011, p. 100.

- ^ a b DuBois 1999, p. 66.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 66; Abram 2011, p. 74.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 92 Price & Mortimer 2014, pp. 517–18.

- ^ a b Abram 2011, p. 92.

- ^ a b c Abram 2011, p. 65.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Abram 2011, p. 66.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 159; Abram 2011, p. 66.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 159; O'Donoghue 2008, p. 60; Abram 2011, p. 66.

- ^ Abram 2011, pp. 5, 65–66.

- ^ a b c d Andrén 2011, p. 851.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 7.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 6.

- ^ Abram 2011, p. 77.

- ^ Davidson 1990, p. 147; Abram 2011, pp. 77–78.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Andrén 2011, p. 847.

- ^ Staecker 1999, p. 89.

- ^ Schnurbein 2003, pp. 133–34.

- ^ Näsström 1999, pp. 177–79.

- ^ Davidson 1990, p. 17.

- ^ DuBois 1999, p. 11; Andrén 2011, p. 846.

- ^ a b DuBois 1999, p. 11.

- ^ Andrén 2005, p. 105.

General sources

edit- Abram, Christopher (2011). Myths of the Pagan North: The Gods of the Norsemen. New York and London: Continuum. ISBN 978-1847252470.

- Andrén, Anders (2005). "Behind "Heathendom": Archaeological Studies of Old Norse Religion". Scottish Archaeological Journal. 27 (2): 105–38. doi:10.3366/saj.2005.27.2.105. JSTOR 27917543.

- Andrén, Anders (2011). "Old Norse and Germanic Religion". In Insoll, Timothy (ed.). The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Ritual and Religion. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 846–62. ISBN 978-0-19-923244-4.

- Andrén, Anders (2014). Tracing Old Norse Cosmology: The World Tree, Middle Earth, and the Sun in Archaeological Perspectives. Lund: Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 978-91-85509-38-6.

- Andrén, Anders; Jennbert, Kristina; Raudvere, Catharina (2006). "Old Norse Religion: Some Problems and Prospects". In Jennbert, Kristina; Raudvere, Catharina; Andrén, Anders (eds.). Old Norse Religion in Long-Term Perspectives. Lund: Nordic Academic Press. pp. 11–14. ISBN 978-9189116818.

- Bek-Pedersen, Karen (2011). The Norns in Old Norse Mythology. Edinburgh: Dunedin Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-906716-18-9.

- Berend, Nora (2007). Christianization and the Rise of Christian Monarchy: Scandinavia, Central Europe and Rus' c. 900–1200. Cambridge University Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-0-521-87616-2.

- Brink, Stefan (2001). "Mythologizing Landscape: Place and Space of Cult and Myth". In Stausberg, Michael (ed.). Kontinuitäten und Bruche in der Religionsgeschichte. Berlin: De Gruyter. pp. 76–112. ISBN 978-311017264-5.

- Clunies Ross, Margaret (1994). Prolonged Echoes: Old Norse Myths in Medieval Northern Society: Volume 1: The Myths. Odense University Press. ISBN 978-8778380081.

- Cusack, Carole M. (1998). Conversion Among the Germanic Peoples. London and New York: Cassell. ISBN 978-0304701551.

- Davidson, H. R. Ellis (1990) [First published 1964]. Gods and Myths of Northern Europe. London: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-013627-2.

- Davidson, H. R. Ellis (1993). The Lost Beliefs of Northern Europe. London and New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-041504937-5.

- Davidson, Hilda Ellis (1992). "Human Sacrifice in the Late Pagan Period in North Western Europe". In Carver, Martin (ed.). The Age of Sutton Hoo: The Seventh Century in North-Western Europe. Woodbridge: Boydell Press. pp. 331–40. ISBN 978-085115330-8.