Operation Market Time was the United States Navy, Republic of Vietnam Navy and Royal Australian Navy operation begun in 1965 to stop the flow of troops, war material, and supplies by sea, coast, and rivers, from North Vietnam into parts of South Vietnam during the Vietnam War. Also participating in Operation Market Time were United States Coast Guard's Squadron One and Squadron Three. The U.S. Coast Guard operated, under U.S. Navy command, heavily armed 82-foot (25 m) patrol boats and large cutters armed with 5-inch naval guns, which were used in battle and gunfire support.

| Operation Market Time | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

|

| ||||

Radar picket escort ships, based in Guam or Pearl Harbor, provided long-term presence at sea offshore to guard against trawler infiltration. Originally built for World War II convoy duty, and then modified for distant early warning ("DEW") duty in the North Atlantic, their sea keeping capability made them ideal for long-term presence offshore where they provided support for Patrol Craft Fast (PCF) boats, pilot rescue and sampan inspection. There were two or three on station at all times. Deployments were seven-months duration, with a four- or five-month turn-around in Pearl. When off station, they alternated duty as Taiwan Defense Patrol, with stops in Subic and Sasebo for refit mid-deployment.

Operation Market Time was one of six Navy duties begun after the Tonkin Gulf Incident, along with Operation Sea Dragon, Operation Sealords, Yankee Station, PIRAZ, and naval gunfire support.

Background

editWhen a trawler was intercepted landing arms and ammunition at Vung Ro Bay in northern Khánh Hòa Province on 16 February 1965, it provided the first tangible evidence of the North Vietnamese supply operation. This became known as the Vung Ro Bay Incident.[1] Operation Market Time was established by the United States Joint Chiefs of Staff at the request of General William C. Westmoreland, commanding general of Military Assistance Command Vietnam. He requested that the U.S. Navy establish a naval blockade of the vast South Vietnam coastline against North Vietnamese gun-running trawlers.[2] The trawlers, usually 100 feet (30 m) long Chinese-built steel-hulled coastal freighters, could carry several tons of arms and ammunition in their hulls. Not flying a national ensign that would identify them, the ships would maneuver "innocently" out in the South China Sea, waiting for the cover of darkness to make high-speed runs to the South Vietnam coastline. If successful, the ships would off load their cargoes to waiting Việt Cộng (VC) or People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) forces.

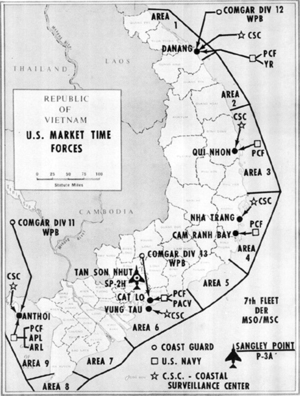

At the time of inception, the Coast Guard contributed seventeen 82 feet (25 m) Point-class cutters while the Navy added approximately fifty ships known as Patrol Craft Fast (PCFs or Swifts) that could reach a maximum speed of 28 knots.[3] In detail, on 16 April 1965 United States Secretary of the Navy Paul Nitze requested Coast Guard assistance with Market Time. On 6 May 1965, the seventeen Point-class cutters were loaded as deck cargo on merchant ships in New York City, Norfolk, New Orleans, Galveston, San Pedro, San Francisco and Seattle for transport to U.S. Naval Base Subic Bay. At Subic Bay each of the cutters was armed with an 81 mm mortar and five .50 caliber machine guns. Coast Guard Squadron One was organized into Division Eleven with eight of the cutters and Division Twelve with nine of the cutters. Division Twelve sailed on 15 July 1965 and arrived at Đà Nẵng on 20 July. Division Eleven sailed on 20 July and arrived at An Thoi on 31 July. An additional nine cutters were provided to form Division Thirteen at Vũng Tàu in early 1966. Each cutter with an eleven-man crew would spend four days on patrol followed by two days alongside a support ship. All 26 cutters were turned over to South Vietnamese crews between 16 May 1969 and 15 August 1970.[1]

Operations

editCoastal surveillance centers

editIn an effort to coordinate all coastal interdiction activities, coastal surveillance centers (CSC) were established at Da Nang, Qui Nhon, Nha Trang, Vung Tau and An Thoi and were manned by Republic of Vietnam Navy (RVNN) and U.S. Navy watchstanders. Reports of possible sightings of suspect vessels from aircraft and watercraft were reported to the CSC's and the appropriate response vessels and aircraft were dispatched to the scene by CSC personnel.[4][5]

Watercraft

editThe objective of Operation Market Time focused on preventing communist ships from infiltrating the South Vietnamese coast to resupply PAVN/VC forces. Beginning officially on 11 March 1965, Market Time featured a picket line of ships along over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of South Vietnamese coast including forces from the U.S. Coast Guard, the U.S. Navy and the RVNN.[6] The operation was originally placed under the control of the Vietnam Patrol Force (Task Force 71). Command shifted to the Commander, Naval Forces Vietnam on 31 July 1965 and designated as Task Force 115.[7] Operation Market Time was originally planned to acquire 54 Swift boats, but that number increased to a total of 84 in September 1965 to thoroughly guard the coast of South Vietnam. These Swift boats were further separated into five groups and assigned to different areas of operation including Division 101 located at An Thoi (working alongside Coast Guard Division 11), Division 102 at Da Nang (with Coast Guard Division 12), Division 103 at Cat Lo (with Coast Guard Division 13), Division 104 based at Cam Ranh Bay and Division 105 at Qui Nhon.[8]

Seaplane tenders USS Currituck, USS Pine Island and USS Salisbury Sound served as flagships for Market Time.

U.S. Navy Martin P-5 Marlin seaplane patrol squadrons, destroyers, ocean minesweepers, PCFs and United States Coast Guard cutters performed the operation. Also playing a key role in the interdictions were the Navy's patrol gunboats (PGs). The PG was uniquely suited for the job because of its ability to go from standard diesel propulsion to gas turbine (turboshaft) propulsion in a matter of a few minutes. The lightweight aluminum and fiberglass ships were fast and highly maneuverable because of their variable-pitch propellers. Most of the ships operated in the coastal waters from the Cambodian border around the south tip of Vietnam up north to Đà Nẵng. Supply ships from the Service Force, such as oilers, would bring mail, movies and fuel.

A significant action of Market Time occurred on 1 March 1968, when the North Vietnamese attempted a coordinated infiltration of four gun-running trawlers. Two of the four trawlers were destroyed by allied ships in gun battles, one trawler crew detonated charges on board their vessel to avoid capture, and the fourth trawler turned tail and retreated at high speed into the South China Sea. LT Norm Cook, the patrol plane commander of a VP-17 P-2H Neptune patrol aircraft operating from Cam Ranh Bay, was awarded a Distinguished Flying Cross for discovering and following two of the four trawlers in the action.

Of the many vessels involved in Operation Market Time, one of the more notable was the USCGC Point Welcome which, on 11 August 1966, was brought under fire by a number of United States Air Force aircraft. This incident of a "blue-on-blue" engagement killed two members of the cutter's crew (one of whom was the commanding officer) and wounded nearly everyone on board.[9]

Aircraft

editTo stop these infiltrations, Market Time was established as a coordinated effort of long range patrol aircraft for broad reconnaissance and tracking. These aircraft, initially SP-5B seaplanes, later P-2 Neptunes and Lockheed P-3 Orions, were armed with Bullpup air-to-surface missiles were capable of engaging these craft directly. Under normal conditions, U.S. and allied surface forces intercepted suspect ships that crossed inside South Vietnam's 12-mile coastal boundary. On the aviation side, some of the patrol squadrons that were involved and flying from South Vietnam, Thailand, or Philippine bases were: VP-1, VP-2, VP-4, VP-6, VP-8, VP-9, VP-16, VP-17, VP-19 VP-22, VP-26, VP-28, VP-40, VP-42, VP-45, VP-46, VP-47, VP-48, VP-49 and VP-50.

Aircraft flew constant and monotonous patrols along 1,200 miles (1,900 km) of coast during Operation Market Time departing from bases ranging from Vietnam (Tan Son Nhut Airbase and Cam Ranh Bay) to the Philippines (Sangley Point) and Thailand (Utapao Airbase). Although the air support missions received little press coverage, their importance to the overall operation cannot be denied. Planes had the ability to cover large expanses of water in a relatively short time and could monitor suspicious vessels lingering in international waters waiting to make a dash for the coast.[10] By October 1967 air surveillance expanded to monitor traffic bound to and from Cambodia as at this point it had become apparent that communist supplies were being shipped to Sihanoukville which were then transported over to the South Vietnamese border in large convoy trucks.[11]

Aftermath

editMarket Time, which operated day and night, fair weather and foul, for eight and a half years, denied the North Vietnamese a means of delivering tons of war materials into South Vietnam by sea. Nonetheless, assessing the overall effectiveness of Operation Market Time is problematic for several reasons. The operation cannot be considered a failure in any sense, but debate over its success continues. The Navy's Operations Evaluation Group stated that in the case of trawler infiltration after the implementation of Operation Market Time just one out of every twenty trawlers were able to reach the South Vietnamese coast undetected.[12]

This number is certainly encouraging, yet it does not fully reflect all possible cases in which craft reached shore unbeknownst to American intelligence. Similar to the high body count numbers in accordance with the doctrine of attrition, scholars fear that boarding and inspection numbers were also inflated by soldiers and commanders.[13] Even considering all of these factors, Market Time had an undeniable effect on infiltration into South Vietnam. Throughout the course of 1966 alone allied forces detected 807,946 watercraft, visually inspected 223,482 of them, and boarded 181,482. Forces also engaged in a total of 482 firefights, killed 161 VC soldiers, and captured 177 while experiencing 21 friendly deaths and 97 other casualties.[14]

A study by the BDM Corporation concluded that at the very least the operation forced the VC to drastically alter its logistic operations. The company also stated that at the beginning of 1966 almost 75% of enemy resupply came from the sea along the South Vietnamese coast. By early 1967 this number had been reduced to just 10%.[15]

Notes

editCitations

editReferences used

edit- Cutler, Thomas J. (1988). Brown Water, Black Berets. Annapolis, MD: United States Naval Institute. ISBN 0-87021-011-4. OCLC 17299589.

- Kelley, Michael P. (2002). Where We Were in Vietnam. Hellgate Press, Central Point, Oregon. ISBN 978-1-55571-625-7.

- Larzelere, Alex (1997). The Coast Guard at War, Vietnam, 1965–1975. Naval Institute Press, Annapolis, Maryland. ISBN 978-1-55750-529-3.

- Noble, Dennis L. (1984). "Cutters and Sampans". Proceedings. 110 (6). United States Naval Institute: 46–53.

- Olson, James S. (2008). In Country: The Illustrated Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War. New York: Metro Books. ISBN 978-1-4351-1184-4. OCLC 317495523.

- Schreadley, R. L. (1992). From the Rivers to the Sea: The U.S. Navy in Vietnam. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-772-0. OCLC 23902015.

- Scotti, Paul C. (2000). Coast Guard Action in Vietnam: Stories of Those Who Served. Hellgate Press, Central Point, Oregon. ISBN 978-1-55571-528-1.

- Summers Jr., Harry G. (1995). Historical Atlas of the Vietnam War. Houghton Mifflin Co., New York, New York. ISBN 978-0-395-72223-7.

Other references not cited in article

edit- Steffes, James ENC Retired, "Swift Boat Down, The Real Story of the Sinking of PCF-19", Xlibris, 2006, ISBN 1-59926-612-1[self-published source]

- Steffes, James ENC Retired, "Operation Market Time, The Early Years 1965-66", Xlibris, 2009, ISBN 978-1-4415-9049-7[self-published source]