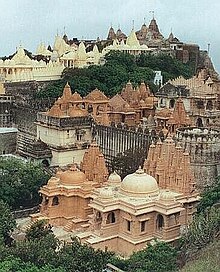

The Palitana temples, often known only as Palitana, are a large complex of Jain temples located on Shatrunjaya hills near Palitana in Bhavnagar district, Gujarat, India. Also known as "Padliptapur of Kathiawad" in historic texts, the dense collection of almost 900 small shrines and large temples have led many to call Palitana the "city of temples".[1] It is one of the most sacred sites of the Śvetāmbara tradition within Jainism. The earliest temples in the complex date as far back as the 11th century CE.[2]

| Shatrunjaya Tirtha, Palitana | |

|---|---|

Pundarikgiri | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Jainism |

| Sect | Śvetāmbara |

| Deity | Rishabhanatha |

| Festivals | Mahavir Janma Kalyanak, Kartik Purnima & Falgun Feri |

| Governing body | Anandji Kalyanji Trust |

| Location | |

| Location | Palitana, Bhavnagar district, Gujarat, India |

| Geographic coordinates | 21°28′58.8″N 71°47′38.4″E / 21.483000°N 71.794000°E |

| Specifications | |

| Temple(s) | 863 |

| Monument(s) | 2700 |

| Elevation | 603 m (1,978 ft) |

The Palitana temple complex is near the top of the hill, in groups called Tonks (Tuks) along the hills' various ridges.[1] The main temple is dedicated to Rishabhanatha, the first Tirthankara; it is the holiest shrine for the Śvetāmbara Murtipujaka sect. Marble is the preferred material of construction. More than 400,000 pilgrims visited the site in 2010.[3]

Jains believe that 23 of the 24 Tirthankaras, all except Neminatha, sanctified Palitana with visits. This makes the site particularly important to the Jain tradition. These temples are reached by most pilgrims and visitors by climbing around 3500 stone steps along a hilly trail. Some hire pallanquins at the base of the hills, to be carried to the temple complex. Palitana, along with the Shikharji in Jharkhand, is believed to be the holiest of all pilgrimage places by the Jain community.[4][5]

Digambara Jains have only one dedicated temple in Palitana.[6] Hingraj Ambikadevi (known as Hinglaj Mata) is considered as the presiding deity of the hill, who is a Jain Yakshini (attendant deity).[7] As the temple complex was built to be an abode for the divine, no one is allowed to stay overnight, including the priests.[8]

Location

editPalitana is a small town about 55 kilometers southwest of Bhavnagar city and 25 kilometers south of Songadh village in Bhavnagar district in southeastern Gujarat. It is midst an arid-marshy terrain near the Gulf of Cambay and the Shetrunji river.[9] About 2 kilometers to the south of Palitana town are twin hilltops with a saddle-like valley with a peak height of about 600 meters. These are the Palitana hills, historically called the Shatrunjaya Hills.[9] The word Shatrunjaya is interpreted as a "place of victory".[9] According to Paul Dundas, a scholar of Jainism, Shatrunjaya hill literally means "the hill which conquers enemies".[10] On these hilltops is a fortified wall complex with space for canons built by the local Hindu ruler after the 14th century to resist any raids and destruction. Within this fortified walls, on the ridges of these hills is the largest collection of Śvetāmbara Jain temples, called the Palitana temples.[11][12]

The steps for the trek to Palitana temples starts in the southern part of the Palitana town, where there a number of monasteries, rest houses, shops and small temples. The steps to the Palitana temples begin to the west of a major active Jain temple and to the east of the newly built Samovsaran Mandir and museum by the Tapa Gaccha subtradition of Jains.[13] The stone-concrete stairs gently wind along the hill, climbing up into the fort and to the summit with temples. Along this climb, are small temples, rest stops with drinking water for the pilgrims and visitors to sit and rest before resuming their trek. Near the fort, the steps fork into two. The eastern side typically is the entrance for a traditional clockwise circumambulation of the temples, while the other the exit. The trek involves climbing over 3500 stone steps.[9][14]

Mythology and history

editIn the traditional texts and beliefs, this sacred hill became important to Jainism millions of years ago, since the age of Adinatha (locally called Adishvera). Adinatha himself lived for 8.4 million purvas ( 1 purva = 70560 billion years), and patronized this Satrunjaya hills site many times in his long life. He is believed to have visited Satrunjaya nearly 700 million times, more than any other Jain site. Thereafter, Satrunjaya has been cherished and patronized by other Tirthankaras of Jainism, including Risabhanatha and his son Bharata. These hills and Palitana host Adinatha's principal temple.[14]

According to the Shatrunjaya Mahatmya by Dhanesvara, a Jaina text in Sanskrit traceable to about the 14th century CE, Mahavira recited the legends of Rishabha to a solemn assembly on Satrunjaya when deity Indra requested him to do so. After nearly 300 verses, the text begins the description of Bharatam Varsham, followed by the glory of Satrunjaya. The text declares it so holy, that even thinking about it "expiates many sins". It then gives 108 alternate names for this site in verses 331 to 335, such as Pundarika, Siddikshetram, Mahabala, Surasaila, Vimaladri, Punyarasi, Subhadra, Muktigeham, Mahatirtham, Patalamula, Kailasa, and others.[15] Of these names, the 11th-century Jaina scholar Hemachandra mentions two: Satrunjaya and Vimaladri.[15]

In the Jain belief, the first Tirthankara Rishabha sanctified the hill where he delivered his first sermon. It was his first disciple Pundarika, who attained Nirvana at Shatrunjay, hence the hill was originally known as "Pundarikgiri". There exists a marble image of Pundaraksvami consecrated in samvat year 1064 (1120 CE) by Shersthi Ammeyaka to commemorate the sallekhana of a muni belonging to the Vidhyadhara Kula.[16]

Bharata Chakravartin, the father of Pundarik and half-brother of Bahubali, is believed in Jain mythistory to have visited Shatrunjaya many times.[17] In some Jain literature, it is claimed to be the site of the first Jaina temple many millions of years ago.[note 1][10][19]

Vividha Tirtha Kalpa, composed by Jinaprabha Suri in the 14th century CE, describes the shrines and legends of Palitana temples.[20]

Shatrunjaya along with Ashtapad, Girnar, Dilwara Temples of Mount Abu and Shikharji are known as Śvētāmbara Pancha Tirth (five principal pilgrimage shrine).[21]

Date

editIn the mythistory[note 2] of Jainism, the early Jaina scholars give the Palitana temples dates ranging from the time of early Tirthankaras (millions of years ago) to 1st millennium BCE. More precise dates emerge in texts such as the Shatrunjaya Mahatmya, which in a verse asserts its own composition of samvat 477 (c. 421 CE), but then proceeds to mention a series of seventeen renovations by mythical Jain and Hindu kings,[note 3] as well as the one that was completed in early 14th century based on epigraphy and other historical records.[24] According to Vividha Tirtha Kalpa, Pandavas along with Kunti attained moksha here.[20]

The Shatrunjaya hills are mentioned in the canonical texts that Śvetāmbara Jains,[note 4] though this mention is found in the later sections broadly accepted to have been completed by about the 5th century. This suggests that the site of Palitana temples was sacred to the Śvetāmbara Jains by about the 5th century, if not earlier.[10] In Saravali, a late section within the Svatambara canonical works that was likely appended in the 11th century, Rishaba's grandson Pundarika is mentioned in the context of Shatrunjaya hills and Palitana temples site, as are Rama, Sita and the Pandava brothers of Hinduism mentioned as doing Tirtha here. Thus, the Palitana temples site was acknowledged in the most important texts of Śvetāmbara Jains, and it was definitely a part of Jaina sacred geography in Gujarat by the 11th century.[10]

Based on epigraphy and architectural considerations, the Palitana temples were built, damaged, restored and expanded over a period of 900 years starting in the 11th century. For example, the Jain text Pethadarasa describes the restorations made by Pethada in 1278 CE after it was damaged and mutilated, while the Jain text Samararasa presents the repairs and restorations in 1315 CE. Epigraphical records found at the site establish that between 1531 and 1594, the temples were damaged, then extensive repairs and restorations were completed with the support of Karmashah and Tejpalsoni after damage to the temples.[24] According to Cousens, hardly anything in the architecture of Palitana temples as they have survived into the modern age, can be dated "earlier than the 12th-century".[25] This may be because earlier temples were built from wood, while stone and marble as construction material was adopted by Gujarati Jain community at Satrunjaya in the 12th century.[26] Two individual items of artwork are from the 11th century – the Pundarika image can be dated to 1006 CE, while another image of layperson here is from 1075 CE.[26]

The damage and destruction of earlier versions of the Palitana temples complex is attributed by Jain texts to the Turks (the name for Muslim armies of different Sultanates). Examples include the raids and destructions in Gujarat during the 13th and 15th century CE, particularly the major destruction in samvat 1369 (c. 1312–3 CE) by Allauddin Khilji of Delhi Sultanate.[27][17][note 5] These destructions are attested by the textual and epigraphical records of Jains, such as those of the Jain scholar and saint Jinaprabha Suri, who presided over the temples. Suri writes in section 1.119 of his Vividha Tirtha Kalpa that the Palitana temples were sacked by the Muslim army in 1311 CE.[29] Further, another evidence is the sudden and near-complete lack of new inscriptions from most of the 16th century, in contrast to inscriptions before and after the 16th century. The Śvetāmbara Murtipujaka (idol worshippers) traditions of Tapa Gaccha, particularly led by Hiravijayasuri, was instrumental in organizing the Jain community to once again restore Palitana temples and complete new large temples, starting in 1593 CE. Thereafter, wealthy patrons added to a proliferation of temples at this site. This tradition of adding temples associated with this site, as well as in and around Palitana continues in the contemporary era. Most of the temples and a large section of the complex as seen by pilgrims and visitors in the contemporary era are between the end of 16th and the 19th century.[10]

In 1656, Murad Baksh – then Governor of Gujarat, and the son of the Mughal emperor Shah Jahan, granted the Shatrunjaya site and Palitana temples as a gift to Shantidas Jhaveri – then the jeweller to his court and the leader of local Jain community.[30][note 6] In 1730 CE, the management of the Palitana temples came under Anandji Kalyanji Trust.[26][27]

Description

editThe Shatrunjaya site has numerous Jain temples, which in Gujarat are called derasar. All these are the Palitana temples. The total number varies by source, with most scholarly counts being close to a 1000. Of these, 108 are large temples, rest are small to tiny shrines that are a part of the chauvisis ensemble (24 identical shrines, one each for a Tirthankara).[27] The entire site is in clusters. A fortified, enclosed cluster of temples is called a Tonk or Tuk. The Palitana temples are in nine Tuks, set on the two ridges of the Shatrunjaya hills.[31]

The nine Tuks are:[32]

- Sheth Narasinh Keshavji Tuk

- Chaumukhji Tuk (Sava-Som Tuk)[33]

- Chhipavasahi Tuk

- Sakar Vasahi Tuk

- Nandishwar Tuk

- Hema Vasahi Tuk

- Modi Tuk[note 7]

- Bala Vasahi Tuk

- Motisha Sheth Tuk

- Ghety Bari Tuk

The most important temples in these Tuks are the Adinath, Kumarpal, Sampratiraja, Vimal Shah, Sahasrakuta, Ashtapada and Chaumukh temple.[34] Some of them are named after the wealthy patrons who paid for the construction.

Architecture and artwork

editThe Palitana temples highlight the Maru-Gurjara architecture found in western and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, primarily Gujarat and Rajasthan. Given its history of damage and rebuilding, the 16th- to 19th-century Palitana temples of Śvetāmbara Jain tradition show the evolution in design principles over this period within the Solanki school. It reflects an ornate style with the North Indian Nagara temples architecture, and is related to the innovations and developments that began in western India around the 10th century with the Kalyana Chalukya dynasty. This architecture is also found in Hindu temples and Digambara Jain tradition temples in this part of India.[35]

This Solanki-school Maru-Gurjara architecture preserves the Nagara Shikhara, yet distinctively favors ornate outer and inner walls with numerous reliefs, sculptures and open pillared halls with the square and circle principle variously applied. Integrated within are andolas (a form of arches) and toranas of different styles, typically highly ornamented.[35] These are found in the region stretching between Gujarat and Telangana. The post 16th-century temples in Palitana, like those found in Rajasthan, look ever more ornamented and precision carved in marble or other materials that became increasingly easier to move from their place of origin. Ceilings, ambulatories and pillars too are lavishly decorated, while domes in concentric shrinking circles help envelop more space and light. The sanctum (garbhagriya) remembers the historic tradition, as do the upper layers of the superstructure.[35] Among the various Tuks at Shatrujaya, the more elaborate and open architecture temples are those built in the 19th century and under the sponsorship of the Anandji Kalyanji Trust.[36]

Main temples

edit- Chaumukh temple

The Chaumukh temple has a large hall, a reminder of Jain community discourses. This is inspired by the first tirthanakara's discourse. It is an ensemble involving buildings with open hall and four entrances so that images would be visible from all four directions. The four sides are called the caturbimba (four sided views).[37]

- Adinath temple

The Adinath temple, which venerates Rishabha, is the main temple (in the apex of the northern ridge of the complex[38]) in the complex and is the grandest. It has ornate architectural motifs, though in its overall plan, it is simpler than the Chaumukh temple. The jewellery collection of this temple is large, which can be seen with special permission from the Anandji Kalyanji Trust. The prayer halls of this temple (renovated in 1157 by Vagabhata) is decorated with ornamental friezes of dragons.[38]

There are three pradakshina routes, followed in a clockwise direction, which are associated with this temple. The first is circular and includes the Sahasrakuta temple, the foot-idols under the Rayan tree, the temple of idols of feet of Ganadhar, and the temple of Simandhar Swami. The second passage passes the new Adishwar temple, Mt. Meru, the temple of Samavasaran temple, and Sammet Shikhar temple. The third passage passes the Ashtapada temple, the Chaumukh temple.[38]

- Adishvara Temple

The Adishvara Temple, dated to the 16th century, has an ornamented spire; its main image is that of Rishabha. The Chaumukh temple, built in 1616 by Setthi Devaraj, has a four-faced Adinatha image deified on a white pedestal, each face turned towards the cardinal directions. The west-side of the shrine is surrounded by Veranda with richly carved pillars and figures of musicians and dancers. There are two sub-shrines dedicated to Gomukha and Chakreshvari near the main entrance.[39]

- Vimal Shah temple

Vimal Shah temple is a square structure with towers. Saraswati devi temple, Narsinh Kesharji temple, and the Samavasaran temple, with 108 life-sketches in sculpture, are also notable. Other notable stops are the Ashok tree, the Chaitra tree, Jaytaleti, four-faced idol of Mahavira, and the artwork related to Kumarpal, Vimalshah and Samprati.

A modern temple, Samvatsarana, was built at the base of the hills of the main temple complex by Tapa Gachha initiative. It has a small museum at the lower level.[9][13] Ashtapadh temple is depiction Ashtapadh (Mount Kailash) where Adinatha is believed to have attained moksha.[40]

In the shrines, on a pedestal, are large figures of Mahavira, sitting with feet crossed in front, like those of Buddha, often decorated with gems, gold plates, and silver.[41] The Adinath temple has an image 2.16 metres (7 ft 1 in) in height of a white-coloured idol in the Padmasana posture. The main iconic image of Adinath, carved in fine piece of marble, has crystal eyes. Devotees offer flowers and sandal paste to the deity as they approach the statue for worship. The quadrangle opposite in front of the temples is elaborately designed. There is another shrine opposite to Adishwara temple is dedicated to Pundarik Swami.

After visiting Adishwara, a temple similar in design, Dilwara temple, is located to the right of the steps used for descending from the main shrine, built in marble. In this temple, Suparswanatha is carved in the centre of a cube-shaped column; Adinatha and Parswanatha adorn the top and bottom of the column. Carvings on the ceiling, floor and the column are very elegantly sculpted. Parswanatha Temple is located in front of this temple.

In 2016, a 108 feet idol of Adinath(Rishabhnatha) was installed.[42][43]

Renovations

editThere have been frequent renovations and many of them are dated to the 16th century. New temples continue to be built here.[44] Renovations occurred at least 16 times during the avasarpinikala (the descending half of the wheel of time):[45][23][46]

| Renovation | Renovator | Times | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1st | Bharat Chakravarti | Adinath | son of Adinath |

| 2nd | King Dandavirya | interim period between Adinath and Ajitnath | – |

| 3rd | Ishaneshvar Indra | Indra of Upper World | |

| 4th | Mahendra | Indra of fourth upper world (dev-lok) | |

| 5th | Brahmendra | Indra of fifth upper world (dev-lok) | |

| 6th | Chamarendra | Indra of Bhavanapatis | |

| 7th | Sagar Chakravarti | Ajitnath | second Chakravarti |

| 8th | Vyantarendra | Abhinandannath | Advised by Abhinandan Swami |

| 9th | King Chandrayasha | Chandraprabha | Advised by his father Chandrashekhar |

| 10th | Chakrayuddha | Shantinath | son of Shantinath |

| 11th | Rama and Lakshmana | Munisuvrata | Ramayana (Hinduism) |

| 12th | 5 Pandavas | Neminatha | Mahabharta (Hinduism) |

| 13th | Javadsha of Mahuva | Vikram Samvat 108 (1st century CE) | A trader from Saurashtra |

| 14th | Bahud Mantri | Vikram Samvat 1213 (11th century) | Wooden temples, reign of Kumarpal |

| 15th | Samarashah Oswal | Vikram Samvat 1371 (13th century) | Rebuilding after the destruction by Sultanate army |

| 16th | Karamashah of Chittorgarh | Vikram Samvat 1587 (16th century) | Rebuilding, with a petition to end pilgrim tax |

It is believed that the 17th renovation will occur in future.[47]

Religious practices

editMost devout Jains prefer to walk up, but elderly pilgrims sometimes opt for a pallanquin (doli) to be manually carried from the town to the hilltop. The temples remain closed for the devotees during the monsoon season. In the month of Phalguna (February/March), Jain pilgrims take a longer route, one passing through five sacred temple sites over a distance of 45 kilometres (28 mi).[citation needed]

The Palitana temples are in clusters traditionally known as tunks (tuks, tonks). As a religious practice they cover their mouth while offering puja to the tirthankaras at the temples so that they don't hurt any insects by swallowing them with an open mouth. Also, for this reason they do not offer open lighted lamps but offer aarti with covered lanterns. The religious practice also involves pilgrimage by fasting throughout the journey to and from the shrines. They also build their temples in white marble to demonstrate purity.[48] Silence and prayers are the order of the day when one is climbing up the hills on pilgrimage.[49] Fasting continues until they have returned to the auditorium of Anandji Kalyanji Trust at the foothill.

Culture

edit- Beliefs

Every devout Jain aspires to climb to the top of the mountain at least once in their lifetime in efforts to attain nirvana, due to its sanctity. The code for the climbers is stringent, in keeping with the rigours of the Jain faith. Food must neither be eaten nor carried on the way. The descent must begin before it is evening, for no soul can remain atop the sacred mountain during the night. The Shatrunjaya hills are considered by many Jains to be more sacred than the temple-covered hills of Jharkhand, Mount Abu and Girnar.

- Festivals

On one special day (Fagun Sud 13), which commonly falls in February/March, thousands of Jain followers visit the temple complex to attain salvation. Three times as many pilgrims come at this time, which is also called "6 Gaon".[50] The special festival day is the "Chha Gau Teerth Yatra" at the temple complex held on Purnima day (Full Moon Day) of Kartika month according to the Jain calendar, Vira Nirvana Samvat (October–November as per the Gregorian Calendar). Jains, in very large numbers assemble on this day at the temple complex on the hills as it opens after 4 months of closure during the monsoon season. During this pilgrimage, considered a great event in the lifetime of devout Jain, pilgrims circumambulate the Shatunitjaya Hills covering a distance of 21.6 km on foot to offer prayers to Adinatha on the Kartik Poornima Day at the top of the hill.[51]

Mahavir Janma Kalyanak, the birthday of Mahāvīra, is a notable festival celebrated at the temple complex. A procession carrying images of the tirthankara is made in huge decorated chariots, concurrently accompanied by religious ceremonies in the temples. Rituals include fasting and giving alms to the poor.[44]

- Navanu, the 99-fold pilgrimage

Navanu is the Jain tradition of repeated pilgrimages to Shatrunjaya hills and Palitana temples. This pilgrimages are typically started in small groups by girls or boys in late teens or early twenties. It includes a period of ascetic practices such as fasting (varshi tap, updhan and others). According to Anadji Kalyanji Trust, an average of 3000 pilgrims every year visit the Palitana temples on Navanu pilgrimage.[52]

Other religions

editAccording to Cousens, the earliest structures and those with pre-15th century architecture were few and spread out. These were mostly Jaina structure, The Hindu temple was constructed by the Jains for the purpose of convenience of the Hindu Priests who managed the Jain temples. There are different beliefs amongst Jains as well as Hindus for the same people. One of the example is the Panch Pandavs. As per Jain texts, these 5 Pandavas came to Palitana / Shatrunjay to attain Moksha. However, as per Mahabharata, these five men meditated in Himalayas in their last days. The Panch Pandava temple behind the Chaumukhi temple is constructed by Jains as per their belief. The Bhulavani temple is dedicated as Yaksha / Yakshini of the Jain temple, and space where the Kumarpala temple now stands in the Vimala Vasi Tuk. Another example is of Shri Krishna Vasudev. As per Jainism, there are 63 Shalaka Purush. Vasudevs is a type of Shalaka Purush and Shri Krishna was the last Vasudev in this time cycle. Shri Krishna was a cousin of Jain's 22rd Tirthankar - Neminath. So, in temples and artwork of Neminatha, Hindu god Krishna is reverentially included in the temples as they are believed to be cousins by the Jain community.

Along the trail from the town to the entrance of the Palitana temples fort walls, there are several small Hindu shrines, typically near rest spaces. These include the Hingraj Ambikadevi (known as Hinglaj Mata), a shrine to Devaki of Krishna fame remembering Kansa legend in black marble, and a small temple to the Hindu deity Hanuman of the Ramayana fame near the spot where the trail splits towards the two gates. Since these characters in the legendary history were real, Jains and Hindus do have different faiths and beliefs. They cannot be labelled as pure Hindu or pure Jain figures. There is reference of Devki as a Sati in Jain texts, so it is but obvious that these shrines were carved out by Jains based on their belief.

Also, on the summit, there is a tomb of a Muslim by the name of Hengar, also called the shrine of Angarsa Pir or Angar Pir. It is unknown who he was and why his tomb (dargah) is on the Shatrujaya hill near the entrance of one of the fort walls. Neither Islamic records or inscriptions of Gujarat nor Jain literature mention him. According to the site research completed by James Burgess, Hengar threw a mace at Adinatha statue and damaged it, but was struck dead in the attempt. Haunted by the death and the dead body, the Jain priests decided to give his bones a burial and entombed him. In contemporary times, a new story has been offered by the caretaker of the dargah, one that claims that he argued with Sultans on behalf of the Jains and prevented damage to the Palitana temples during the Muslim invasions. This story of AngarSha protecting the Palitana temples is mentioned very well in many history books, books of Mughals poets as well as Jain texts. However, few do not believe this story and want to imagine things otherwise. Jain temples of Palitana are mentioned in texts, posters, drawings dating back to 8th and 9th century. However, there is no mention of Palitana or Shatrunjay in any of the Hindu texts. The Hindu texts, revolve and evolved around Himalayas as well as North and North plains of India.

Gallery

edit-

Adishwar Temple

-

A temple in Palitana temples complex

-

Palitana temples complex

-

Palitana Temples distant view

-

Temple Inside Chaumukhji Tonk

-

Samovsaran Mandir, a modern temple and museum at the base of the hills (Tapa Gaccha subtradition of Jains)[13]

-

Torana before the Samovsaran Mandir Palitana

-

Adinath temple depicted on 1949 Indian postage stamp

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ Bharata installed 24 life-size idols of all 24 Tirthankaras along with an image of himself and his 99 brothers. The location of this temple is unclear. In Jain Literature dated to the second half of the 1st millennium, such as the Āvaśyaka Niryukti, gāthā 435, it is identified as Mount Ashtapada, a mythical mountain in Himalayas. Hemchandra identified the location of first Jain temple with Shatrunjaya. Ashtapada is frequently identified with Mount Kailash now.[18]:15, 97

- ^ Mythistory is the synthesis of myth and history.[22]

- ^ These include the Rama of Ramayana fame, and the Pandava brothers of the Mahabharata fame.[23]

- ^ This is not found in Digambara canonical literature.

- ^ Another Jain text that records this destruction and reconstruction is the Nabhinandanoddhara. This text, states Phyllis Granoff – a scholar of Indian religion and history, is contemporaneous to the Palitana temples destruction by Allaudin Khilji. It commemorates their restoration by the Jain layperson Samara, and celebrates those artisans and Jains who had the courage to rebuild the temples despite personal danger before the Sultan.[28]

- ^ This gift states that Shatrunjaya is a place of worship and pilgrimage for the Hindus [Jains were considered Hindus by Muslim rulers], and no government official shall interfere with these worshippers and pilgrims in any way. This order was later clarified to include an exemption from taxes and demands on the temples and pilgrims.[30]

- ^ Sometimes called Prema Vasahi Tuk.

References

edit- ^ a b Burgess & Spiers 1910, p. 24.

- ^ James Burgess (1977). The Temples of Palitana in Kathiawad. South Asia Books. ISBN 978-0-8364-0021-2.

- ^ Hardenberg 2010, p. 2.

- ^ "Jains". www.philtar.ac.uk. Archived from the original on 13 October 2007.

- ^ John E. Cort, Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, p.120. Oxford University Press (2010). ISBN 0-19-538502-0

- ^ Peter 2010, p. 352.

- ^ Suriji 2013, p. 31.

- ^ "Palitana Temples". Government of Gujarat. Archived from the original on 26 December 2017. Retrieved 26 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Arnett 2006, pp. 164–165.

- ^ a b c d e Dundas 2002, p. 222.

- ^ Cousens 1977, pp. 73–75.

- ^ Ku, Hawon (2014). "Representations of Ownership: The Nineteenth-Century Painted Maps of Shatrunjaya, Gujarat". Journal of South Asian Studies. 37 (1). Taylor & Francis: 3–21. doi:10.1080/00856401.2013.852289. S2CID 145090864.

- ^ a b c Cort 2010, pp. 120–121.

- ^ a b Cousens 1977, pp. 73–79.

- ^ a b Burgess 1931, pp. 2–6.

- ^ Some Inscriptions and Images on Mount Satrunjaya, Ambalal P Shah, Mahavir Jain Vidyalay Suvarna Mahotsav Granth Part 1 January 2002, p. 164

- ^ a b Davidson & Gitlitz 2002, p. 419.

- ^ Shah 1987.

- ^ Ku 2011, pp. 1–22.

- ^ a b Dalal 2010, p. 1072.

- ^ Cort 2010, p. 132.

- ^ Joseph Mali (1991), Jacob Burckhardt: Myth, History and Mythistory, History and Memory, Vol. 3, No. 1, Indiana University Press, pp. 86–118JSTOR 25618612

- ^ a b Kanchansagarsuri 1982, pp. 17–22.

- ^ a b Kanchansagarsuri 1982, pp. vi–viii.

- ^ Cousens 1977, pp. 74–76.

- ^ a b c Dundas 2002, p. 223.

- ^ a b c Yashwant K. Malaiya. "Shatrunjaya-Palitana Tirtha". Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ^ Phyllis Granoff 1992, pp. 305–308.

- ^ Dundas 2002, pp. 222–223.

- ^ a b Burgess 1977, p. 14.

- ^ Julia Hegewald 2015, pp. 120, 138, footnote 33.

- ^ Kanchansagarsuri 1982, pp. 22–27, xiii.

- ^ "Nobility of Savchand and Somchand".

- ^ Bansal 2005, p. 102.

- ^ a b c Julia Hegewald 2015, pp. 116–122.

- ^ Julia Hegewald 2015, p. 122.

- ^ Pereira 1977, p. 16.

- ^ a b c Deshpande 2005, pp. 418–419.

- ^ Burgess & Spiers 1910, pp. 28–29.

- ^ Burgess & Spiers 1910, p. 29.

- ^ Bettany 1890, p. 340.

- ^ Palitana 108 feet high statue of Adinath dada.

- ^ "About Palitana - PALITANA ONLINE". www.palitanaonline.com. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017.

- ^ a b Desai 2007, p. 247.

- ^ Shetrunjay Giriraj Aaaradhana, pp. 3–5.

- ^ Burgess & Spiers 1910, p. 27.

- ^ Shetrunjay Giriraj Aaaradhana, pp. 25–27.

- ^ Deshpande 2005, pp. 418–420.

- ^ Bruyn et al. 2010, p. 597.

- ^ "6 Gaon Yatra" (PDF). jainuniversity.org.

- ^ Pilgrims flock Palitana for Kartik Poornima yatra.

- ^ Hardenberg 2010, p. 3.

Bibliography

editBooks

edit- Burgess, James; Spiers, R. Phené (1910). History of Indian and Eastern architecture (PDF). London: John Murray (publishing house).

- Burgess, James (1931), The Starunjaya Mahatmyam (Based on Albert Weber's translation of Sanskrit manuscript, 1st edition: 1902), OCLC 1014906580

- Burgess, James (1977), The temples of Śatruñjaya : the celebrated Jaina place of pilgrimage, near Palitana in Kaṭhiawaḍ, OCLC 3319533

- Cort, John (2010), Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-973957-8

- Cousens, Henry (1977), Somanatha and Other Medieval Temples of Kathiawad (1931), OCLC 1015136237

- Deshpande, Aruna (2005), "India:Divine Destination", Palitana, Crest Publishing House, pp. 418–419, ISBN 81-242-0556-6

- Phyllis Granoff (1992), "The Householder as Shaman Jain Biographies of Temple Builders", East and West, 42 (2/4): 301–317, JSTOR 29757040

- Suriji, Acharya Gunaratna (2013), A Visit to Shatrunjaya: Journey to the holiest pilgrimage of Jainism, Multy Graphics, ISBN 9788192660707, retrieved 2 October 2017

- Bruyn, Pippa de; Bain, Keith; Allardice, David; Joshi, Shonar (2010), Frommer's India, John Wiley & Sons, ISBN 978-0-470-64580-2, retrieved 20 December 2012

- Julia Hegewald (2019), Jaina Temple Architecture in India: The Development of a Distinct Language in Space and Ritual, Hindi Granth Karyalay, ISBN 978-81-88769-71-1

- Julia Hegewald (2015), "The International Jaina style?, Maru-Gurjara Temples under the Solankis, throughout India and in the Diaspora", Ars Orientalis, 45, Smithsonian, Freer Gallery of Art

- Kanchansagarsuri, Acharya (1982), Shri Shatrunjay Giriraj Darshan in Sculptures and Architecture, Aagamoddharak Granthmala

- Melton, J. Gordon (2011), Religious Celebrations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations: An Encyclopedia of Holidays, Festivals, Solemn Observances, and Spiritual Commemorations, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-59884-205-0, retrieved 21 December 2012

- Peter, Berger (2010), The Anthropology of Values: Essays in Honour of Georg Pfeffer, Pearson Education India, ISBN 978-81-317-2820-8, retrieved 21 December 2012

- Singh, Sarina; Benanav, Michael; Blasi, Abigail; Clammer, Paul; Elliott, Mark; Harding, Paul; Mahapatra, Anirban; Noble, John; Raub, Kevin (2015), Lonely Planet India, Lonely Planet, ISBN 9781743609750

- Shetrunjay Giriraj Aaaradhana (PDF) (in Gujarati), Surat: Roop Nakoda Cheritable Trust, pp. 77, 3–5, 25–27

- Arnett, Robert (2006), India Unveiled, Atman Press, ISBN 978-0-9652900-4-3, retrieved 17 December 2012

- Taylor, Max T. (2011), Many Lives, One Lifespan: An Autobiography, Xlibris Corporation, ISBN 978-1-4628-8799-6, retrieved 17 December 2012

- Dalal, Roshen (2010) [2006], The Religions of India: A Concise Guide to Nine Major Faiths, Penguin books, ISBN 978-0-14-341517-6

- Desai, Anjali H. (2007), India Guide Gujarat, India Guide Publications, ISBN 978-0-9789517-0-2

- Dundas, Paul (2002), The Jains, Psychology Press, ISBN 9780415266055

- Shah, Umakant Premanand (1987), Jaina-rūpa-maṇḍana: Jaina iconography, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-208-X

- Davidson, Dr Linda Kay; Gitlitz, David Martin (2002), Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland : An Encyclopedia, ABC-CLIO, ISBN 978-1-57607-004-8, retrieved 17 December 2012

- Pereira, Jose (1977), Monolithic Jinas The Iconography Of The Jain Temples Of Ellora, Motilal Banarsidass, ISBN 978-81-208-2397-6, retrieved 17 December 2012

Web

edit- "Pilgrims flock Palitana for Kartik Poornima yatra". The Times of India. 2 November 2009. Archived from the original on 25 October 2012. Retrieved 3 November 2009.

- Bettany, George Thomas (1890), The world's religions: a popular account of religions ancient and modern, including those of uncivilised races, Chaldaeans, Greeks, Egyptions, Romans; Confucianism, Taoism, Hinduism, Buddhism, Zoroastrianism, Mohammedanism, and a sketch of the history of Judaism and Christianity (Public domain ed.), Ward, Lock, retrieved 17 December 2012

- Ku, Hawon (2011). "Temples and Petrons: The Nineteenth-century Temple of Motisha at Shatrunjaya" (PDF). International Journal of Jaina Studies. 7 (2). Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 September 2011. Retrieved 2 January 2017.

- Hardenberg, Andrea Luithle (2010). "The 99-fold pilgrimage to Shatrunjaya". Goethe University Frankfurt.

- Lodha, Jain Chanchalmal (2013), History of Oswals, Panchshil Publications, ISBN 978-81-923730-2-7

- Bansal, Sunita Pant (2005), Enclopaedia of India, Smriti Books, ISBN 978-81-87967-71-2, retrieved 17 December 2012

- "Palitana 108 feet high statue of Adinath dada". Dainik Bhaskar. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

Further reading

edit- John E. Cort, Framing the Jina: Narratives of Icons and Idols in Jain History, Oxford U Press (2010). ISBN 0-19-538502-0

External links

edit- Article: Mount Śatruñjaya on JainPedia