Mississippi State Penitentiary (MSP), also known as Parchman Farm, is a maximum-security prison farm located in the unincorporated community of Parchman in Sunflower County, Mississippi, in the Mississippi Delta region. Occupying about 28 square miles (73 km2) of land,[3][4] Parchman is the only maximum security prison for men in the state of Mississippi, and is the state's oldest prison.[3][4][2]

Parchman | |

|---|---|

| Mississippi State Penitentiary | |

Entrance to the Mississippi State Penitentiary | |

| Coordinates: 33°55′54″N 90°33′3″W / 33.93167°N 90.55083°W | |

| Elevation | 144 ft (44 m) |

| Time zone | UTC−6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−5 (CDT) |

| ZIP Code | 38738 |

| Area code | 662 |

| GNIS feature ID | 675442[1] |

| Website | mdoc.state.ms.us |

| 675442 is the GNIS ID for the populated place. The GNIS ID for the "building" is 707754.[2] | |

Begun with four stockades in 1901, the Mississippi Department of Corrections facility was constructed largely by state prisoners. It has beds for 4,840 inmates. Inmates work on the prison farm and in manufacturing workshops. It holds male offenders classified at all custody levels—A and B custody (minimum and medium security) and C and D custody (maximum security). It also houses the male death row—all male offenders sentenced to death in Mississippi state courts are held in MSP's Unit 29—and the state execution chamber. The superintendent of Mississippi State Penitentiary is Marshall Turner. There are two wardens, three deputy wardens, and two associate wardens.[5]

Female prisoners are not usually assigned to MSP; Central Mississippi Correctional Facility, also the location of the female death row, was for a time the only state prison in Mississippi designated as a place for female prisoners.[3]

History

editThis section needs additional citations for verification. (June 2023) |

For much of the 19th century after the American Civil War, the state of Mississippi used a convict lease system for its prisoners; lessees paid fees to the state and were responsible for feeding, clothing and housing prisoners who worked for them as laborers.[citation needed]

In 1900 the Mississippi State Legislature appropriated US$80,000 for the purchase of the Parchman Plantation, a 3,789-acre (1,533 ha) property in Sunflower County.[6] What is now the prison property was located at a railroad spur called "Gordon Station".[7]

Founding the Mississippi State Penitentiary (1901)

editThe state of Mississippi purchased land in Sunflower County in January 1901 to establish a state prison.[8] In 1901 four stockades were constructed, and the state moved prisoners to begin clearing land for crop cultivation.[6] The land was undeveloped Mississippi Delta bottomland and forest, fertile but dense with undergrowth and trees.[9]

Around the time the Mississippi State Penitentiary (MSP) opened, Sunflower County residents objected to having executions performed at the prison. They feared that the county would be stigmatized as a "death county". Mississippi originally performed executions of condemned criminals in their counties of conviction.[10]

The Mississippi Department of Archives and History says that MSP "was in many ways reminiscent of a gigantic antebellum plantation and operated on the basis of a plan proposed by Governor John M. Stone in 1896". Prisoners worked as laborers in its operations.[8] In the fiscal year 1905, Parchman's first year of operations, the State of Mississippi earned $185,000 (more than $4.6 million in 2009 dollars) from Parchman's operations.[11]

Originally, Parchman was one of two prisons designated for black men, with the other prisons housing other racial and gender groups.[12]

In 1909, the State of Mississippi acquired 2,000 acres (810 ha) adjacent to the MSP territory, resulting in MDOC having 24.7 sq mi (64 km2) in the Mississippi Delta.[12] As time passed, the state began to consolidate most penal operations in Parchman, making other camps hold minor support roles.[13] In 1916, MDOC bought the O'Keefe Plantation in Quitman County, near Lambert. Originally this plantation was a separate institution, the Lambert Farm.[12] The facility later became Camp B.

By 1917, the Parchman property had been fully cleared. The administration divided the facility into a series of camps, housing black and white prisoners of both genders.[13] By 1917 12 male camps and one female camp were established, with racial segregation maintained throughout. The institution became the main hub of activity for Mississippi's prison system.[8] In 1937, during the Great Depression, the prison had 1,989 inmates.[14]

Around the 1950s, residents of Sunflower County were still opposed to the concept of housing an execution chamber at MSP. In September 1954, Governor Hugh L. White called for a special session of the Mississippi Legislature to discuss the application of the death penalty.[10] During that year, the prison installed a gas chamber for on-site executions. It replaced a mobile electric chair, which, between 1940 and February 5, 1952, had been transported to various counties for executions at prisoner's native grounds. In 1942, the prison saw the end of convict leasing. The first person to be executed in the gas chamber was Gearald A. Gallego, on March 3, 1955.[15]

Parchman Farm and the Freedom Riders (1961)

editIn the spring of 1961, Freedom Riders went to the American South to work for desegregation of public facilities serving interstate transportation, as segregation of such facilities and buses had been declared unconstitutional. Violence engulfed the Riders in Alabama, and the federal government intervened. Finally the governors of Alabama and Mississippi agreed to protect the riders, in exchange for being allowed to arrest them. The Governor of Mississippi, Ross Barnett, did not permit violence against the protesters, but arrested the riders when they reached Jackson, Mississippi. By the end of June, 163 Freedom Riders had been convicted in Jackson and many were jailed in Parchman.[16] On June 15, 1961, the state government sent the first set of Freedom Riders from Hinds County Prison to Parchman; to make the protesters as uncomfortable as possible, they were put to work on chain gangs. The first group sent to the farm were 45 male Freedom Riders, 29 blacks and 16 whites.[17] A call went out across the country to keep the Freedom Rides going and "fill the jails" of Mississippi. At one time, 300 Freedom Riders were imprisoned at Parchman Farm. The prison authorities forced the freedom riders to remove their clothing and undergo strip searches. After the strip searches, Deputy Tyson met the freedom riders and began intimidating them.[18] He began by mocking the Freedom Riders, telling them since they wanted to march all the time, they could march right to their cells, and he would lead them.[19] "When they arrived from Jackson, they were stripped of their clothing, and given a tee shirt and loose-fitting boxer shorts ... no more. It was the beginning of many steps to try to intimidate and humiliate the Freedom Riders. They were denied most basic items, such as pencils and paper or books."[20] David Fankhauser, a Freedom Rider at Parchman Farm, said,

In our cells, we were given a Bible, an aluminum cup and a tooth brush. The cell measured 6 × 8 feet with a toilet and sink on the back wall, and a bunk bed. We were permitted one shower per week, and no mail was allowed. The policy in the maximum security block was to keep lights on 24 hours a day.[20]

Fankhauser described the meals:

Breakfast every morning was black coffee strongly flavored with chicory, grits, biscuits and blackstrap molasses. Lunch was generally some form of beans or black-eyed peas boiled with pork gristle, served with cornbread. In the evening, it was the same as lunch except it was cold.[20]

The Governor of Mississippi, Ross Barnett, visited the farm a few times to check on the activists. He reportedly told the guards to "break their spirit, not their bones".[21] The governor ordered the activists to be kept away from all other inmates and in maximum security cells. With that order given, the Freedom Riders were stuck in their cells for the most part with little to do. They reportedly enthusiastically sang Freedom Songs, mostly direct descendants of slave spirituals. They made up songs to fit their new place.[22]

As the 45 Riders struggled in prison, many others were heading South to join the Freedom Rides. Winonah Myers was one of the women who went South and was eventually jailed for her activism. She witnessed the treatment first hand. She was treated just as the men were, with bad living quarters and worse clothing and meals.[23] Although most of the Freedom Riders were bailed out after a month, Myers was the last to leave. The riders' experiences at Parchman gave the Freedom Riders credibility in the Civil Rights Movement.[20]

1970s–1990s

editIn 1970, civil rights lawyer Roy Haber began taking statements from inmates, which eventually ran to 50 pages detailing murders, rapes, beatings and other abuses they had suffered in Parchman from 1969 to 1971. Four Parchman inmates brought a suit against the prison superintendent in federal district court in 1972, alleging their civil rights under the United States Constitution were being violated by the infliction of cruel and unusual punishment.[24] In the case, Gates v. Collier (1972), the federal judge William C. Keady found that Parchman Farm violated the Constitution and was an affront to 'modern standards of decency'. Among other reforms, the accommodation was made fit for human habitation, and the trusty system, (where lifers were armed with rifles and set to guard other inmates), was abolished.[25][26] The state was required to integrate the prison facilities, hire African-American staff members, and construct new prison facilities.[11]

In the 1970s, the Governor of Mississippi William L. Waller organized a blue-ribbon committee to study MSP. The committee decided that the state should abandon MSP's for-profit farming system and hire a professional penologist to head the prison.[27] On July 1, 1984, the Legislature of Mississippi amended §§ 99-19-51 of the Mississippi Code; the new amendment stated that prisoners who committed capital crimes after July 1, 1984 would be executed by lethal injection.[15]

In the mid-1980s, several state law enforcement officials and postal inspectors went to Parchman to end a widespread scam involving forged money orders.[28]

In 1985, area farmers still referred to the facility as being the "Parchman Penal Farm", even though the facility was officially named the "Mississippi State Penitentiary".[29] During that year MSP had over 4,000 prisoners, including 200 women in a few of the camps.[29] When the Central Mississippi Correctional Facility (CMCF) opened in January 1986, all women who were incarcerated at MSP were moved to the new facility.[30]

The BBC filmed Fourteen Days in May (1987) at Parchman. The documentary followed the last two weeks of the life of Edward Earl Johnson, who was executed in the prison's gas chamber.

In 1997, several prison guards were arrested, accused of illegally interfering with prisoner mail.[31] On March 18, 1998, the legislature made another amendment: removing the gas chamber as a method of execution.[15]

2000s to 2020s

editThe lethal injection table was first used for executions in 2002.[10]

On November 17, 2003, Larry Hentz escaped from Unit 24B of MSP;[32] he was believed to have been traveling with his wife.[33] The escapee and his wife were captured in San Diego, California on December 11, 2003.[34] Hentz was returned to prison.[when?]

In 2005, Tim Climer, the executive director of the Sunflower County Economic Development District, stated that he wanted to develop MSP as a tourist attraction by establishing an interpretive center.[35]

In 2010, the Mississippi State Penitentiary became the first correctional facility in the United States to install a system to prevent contraband cell phone usage by inmates. The managed access system was to prevent the authentication and operation of contraband wireless devices within the prison grounds. Other prisoners, visitors and guards had been smuggling in cellphones as whole units or in pieces for later re-assembly and use.[36] Federal Communications Commission regulations do not allow for devices which interfere with communications on licensed frequencies; The Communications Act only allows a federal agency jam frequencies.[37] The managed access system renders unauthorized devices useless within the prison; it relieves the administration of having to locate or confiscate the devices. It permits authorized devices to operate unimpeded. The technology avoids the legal impediments associated with competing technologies for cell detection and cell-jamming. It ensures that all emergency 911 calls are permitted to complete. Christopher Epps, Commissioner of MDOC, announced the system on September 8, 2010, and suggested that it provided a model for other prisons to use to reduce contraband cell phones.[36] Due to the installation of the system, between August 6, 2010 and September 9, 2010, more than 216,320 texts and calls were blocked.[citation needed]

Between 2014 and 2020, $215 million was cut from the Mississippi Corrections budget,[why?] resulting in increasing pressure on all Mississippi prisons.[38] The 2019 annual inspection report for the prison includes numerous health and safety concerns including broken toilets, sinks and showers, unsanitary kitchens, cells with dangerous electrical fittings and inmates sleeping without mattresses. Photographs illustrating the concerns were included.[39] The 2020 Department of Health report indicates that some progress has been made, but still includes a list of sanitary concerns running to 14 pages which include the same concerns, with the exception of missing mattresses. Photographs are provided.[40] During 2019 and 2020 there were a series of inmate deaths.[41][42] The Commissioner of the Department of Corrections resigned at this time.[43] Eight prisoners died in January 2020 through suicide or violence.[44]

Later in January 2020, it was reported in the press that the prison had closed Unit 29 due to infrastructure issues, and was arranging for prisoners to be housed in prison facilities outside of Parchman.[45] However, Unit 29 has remained open. The 2021 Department of Health Report contains a three page list of health, safety and hygiene deficiencies identified in the Unit 29 accommodation for prisoners.[46]

In February 2020, a federal lawsuit was filed on behalf of over 150 inmates by rappers Jay-Z and Yo Gotti regarding "inhumane and dangerous conditions" at the prison.[47] A Federal Department of Justice Civil Rights investigation began in February 2020, to examine whether prisoners were adequately protected from violence in Parchman and three other Mississippi state prisons, whether Parchman failed in its responsibility for suicide prevention and mental-health care, and whether there were excessive use of solitary confinement in Parchman.[48]

In April 2022, the Justice Department reported that conditions at the facility were inhumane due to years of neglect by the state.[49]

Location and composition

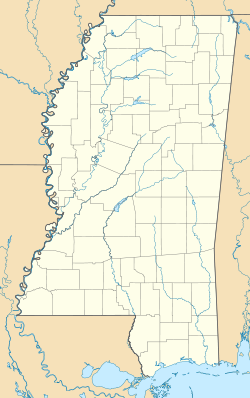

editMississippi State Penitentiary is in an unincorporated area in Sunflower County, Mississippi.[50]

The prison which occupies 18,000 acres (7,300 ha) of land, has 53 buildings with a total of 922,966 square feet (85,746.3 m2) of space. As of 2010 the institution can house 4,536 inmates. 1,109 people, as of 2010, work at MSP. Most of MDOC's agricultural enterprise farming activity occurs at MSP. Mississippi Prison Industries has a work program at MSP, with about 190 inmates participating.[51] The road from the front entrance to the back entrance stretches 5.4 miles (8.7 km).[52] Donald Cabana, who served as the superintendent and executioner of MSP, said, "the sheer magnitude of the place was difficult to comprehend on first viewing."[53]

"Parchman" appears as a place on highway maps. The "Parchman" dot represents the MSP main entrance and several MSP buildings, with the prison territory located to the west of the main entrance.[54] The main entrance, a metal gate with "Mississippi State Penitentiary" in large letters,[54] is located at the intersection of U.S. Route 49W and Mississippi Highway 32,[55] on the west side of 49W.[54]

The Mississippi Blues Trail marker is located at the Parchman main entrance.[56] Passersby are not permitted to stop to photograph buildings at the Parchman main entrance.[57] The rear entrance is about 10 miles (16 km) east of Shelby, at MS 32.[29] Known as the "Back Gate", this entrance was closed from 2017 to 2022 to stop smuggling of goods.[58] A private portion of Highway 32 extends from the main entrance of MSP to the rear entrance of MSP.[59] U.S. 49W is a major highway used to travel to MSP.[16]

The prison facility is located near the northern border of Sunflower County.[60] The City of Drew is 8 miles (13 km) south of MSP,[52] and Ruleville is about 15 miles (24 km) from MSP.[61] Parchman is south of Tutwiler,[62] about 90 miles (140 km) south of Memphis, Tennessee,[7] and about 120 miles (190 km) north of Jackson.[63]

Throughout MSP's history, it was referred to as "the prison without walls" due to the dispersed camps within its property.[6] Hugh Ferguson, the director of public affairs of MSP, said that the prison is not like Alcatraz, because it is not centralized in one or several main buildings. Instead MSP consists of several prison camps spread out over a large area, called "units". Each unit serves a specific segment of the prison population, and each unit is surrounded by walls with barbed tape.[64]

The perimeter of the overall Parchman property has no fencing. The prison property, located on flat farmland of the Mississippi Delta, has almost no trees. Ferguson said that a potential escapee would have no place to hide. Richard Rubin, author of Confederacy of Silence: A True Tale of the New Old South, said that MSP's environment is so inhospitable for escape that prisoners working in the fields are not chained to one another, and one overseer supervises each gang.[65] A potential escapee could wander for days without leaving the MSP property.[66]

As of 1971, guards patrol MSP on horseback instead of on foot.[53] The rear entrance is protected by a steel barricade and a guard tower.[29] In 1985 Robert Cross of the Chicago Tribune said "The physical surroundings – cotton and bean fields, the 21 scattered camps, the barbed wire enclosures – suggest that nothing much has changed since the days, early in this century, when outsiders could visit Parchman State Penal Farm only on the fifth Sunday of those rare months containing more than four."[29]

MSP has two main areas, Area I and Area II. Area I includes Unit 29 and the Front Vocational School. Area II includes Units 25–26, Units 30–32, and Unit 42. Seven units house prisoners.[3] As of the 1970s and 1980s, the prison grounds had small red houses that were used for conjugal visits.[29][67] The prison offered conjugal visits until February 1, 2014.[68]

Inmate housing units

editSix units currently house prisoners.[69] Units that currently function as inmate housing include:[3][70]

- Unit 25

- In the mid-2000s Unit 25 had the Pre-Release/Job Assistance Alcohol and Drug Therapeutic Community After Care Program, which had 48 beds. The program was for offenders who are about to be released from prison.[71]

- Unit 26

- Units 26, 27, and 28, which in total have a capacity of 388 people, together had a price tag of $3,450,000.[30]

- Unit 29

Unit 29 (1992) - Unit 29, a 16-building medium security complex, opened in 1980 and designed by Dale and Associates.[72] Unit 29 houses all male death row inmates in MDOC.[3]

- The building, which was under construction in the 1970s and originally had a capacity of 1,456, had a construction cost of $22,045,000.[30] In 2000, a prisoner riot occurred at Unit 29, leading to some injuries.[73] Renovations occurred in 1998, including the conversion of dormitory units into cell units.[72] Unit 29 is the primary farming support unit of MSP. It has 1,561 beds,[3] which house minimum, medium, and close custody inmates. The unit is the prison's largest in terms of prisoner capacity.[51] In the mid-1990s, Unit 29 was the main maximum security camp for the population. Most inmates started their stays in Unit 29, and almost every prisoner went through the unit.[64] Renovations of Unit 29 in the financial year of 2000 added about 240 beds.[74] Carrothers Construction did phase I of the renovations for $20,278,000.[75] By 2001, MDOC built a kitchen and had converted half of Unit 29's open bay dormitories to individual cells; together the changes had a price tag of $21,760,284 of U.S. Department of Justice grant money.[76] Unit 29-A houses the A&D Treatment Program for Special Needs program, which is for prisoners with HIV/AIDS who are more than 6 months and within 30 months of their release dates.[77] In 2020 J Building (one of 5 Buildings making up Unit 29) was partially closed due to deterioration.[45] J building continues to house death row inmates.[40]

- Unit 30

- Unit 30 is the education and drug treatment facility.[78] It was designed by Dale and Associates.[79] Unit 30, a part of the Alcohol and Drug Therapeutic Community Treatment Centers (ADTC-TC), has 480 beds. Unit 30 has two housing buildings, A and B, and each building has two housing zones, A and B. Each zone houses 108 prisoners.[77] Previously each zone housed 120 prisoners.[71]

- Unit 31

- Unit 31 serves as the unit for inmates with severe disabilities.[80] The unit includes a 12-week alcohol and drug program based on principles of Alcoholics Anonymous.[77]

- Unit 32

- Unit 32, a 34.8-acre (14.1 ha) prison unit,[81] was the designated unit of housing for maximum security and death row convicts.[82] and Unit 32 served as MSP's lockdown unit.[64] Unit 32, designed by Dale and Associates,[79] has "Supermax" cells.[83]

- The U32 housing facility has five two story housing facilities, a recreation building, and external structures such as guntowers. Each housing building has 200 cells and 82 square feet (7.6 m2) of living space. Each housing building was made of precast concrete, and 6,700 cubic yards of concrete and 500,000 pounds (230,000 kg) of reinforcing steel were used to build each housing building.[81] Building A (Alpha Building) served as the maximum security area.[84][85] Building B (Bravo Building) also housed closed custody prisoners.[85] Building C (Charlie Building) served as death row.[86][87] Unit 32 was intended to reduce maintenance necessities by using durable structure and equipment and to allow prison administrators to establish a high level of control over U32's residents. The 18.8-acre (7.6 ha) Unit 32 Support Facility houses administrative offices, a canteen, medical services, a library, and a visitation area.[81] With Unit 32 closed, Parchman had about 1,000 empty spaces for prisoners. MDOC has continued to maintain Unit 32 so the state can house contract prisoners there.[88] In 2020, MDOC re-opened Unit 32 despite prisoner complaints of poor conditions.[89]

- Unit 42

- Unit 42, the prison hospital, has 54 beds.[3] In terms of capacity it is the smallest residential unit.[51] The prison hospital serves female inmates throughout the MDOC system.[90] In December 2009, MDOC opened the Compassionate and Palliative Care Unit, a hospice for dying prisoners, in the hospital.[91]

In 2010, MDOC classified 13 units as "closed housing units".[69] All of the units in the prison that formerly housed prisoners and no longer function as inmate housing include:[70]

- Unit 4

- Unit 10

- Units 10, 12, and 20, which together housed 300 people, together had a total cost of $1,000,000.[30]

- Unit 12

- Unit 12 had the pre-release operations.[92]

- Unit 15, Building B

- Unit 16

- The unit, with a capacity of 68 people, was built in the 1970s for $3,000,000.[30]

- Unit 17

- Unit 17 houses the execution chamber for condemned inmates.[93] A condemned prisoner is transferred to a holding cell next to the death chamber 48 hours before the scheduled time of his or her execution.[51] Cell No. 14 is used to house inmates prior to execution. The execution chamber is a 10-foot (3.0 m) by 15-foot (4.6 m) room.[94]

- Unit 17 is west of Guard Row. It is a one story building with a flat roof. Reilly Morse of the Institute of Southern Studies said that dirt surrounded the unit, and no vegetation was present.[95]

- In 1961, the State of Mississippi incarcerated Freedom Riders in the unit.[95] Unit 17's prisoner housing was closed on October 25, 2004.[96] At one time, the 56-bed Unit 17 housed the prison's death row.[97]

- K-9

- Unit 20

- Fire House

- Unit 22

- Units 22 and 23 and the prison hospital, which in total have a capacity of 324 people, together had a price tag of $1,850,000.[30]

- Unit 23

- Unit 24

- The unit, with a capacity of 192 people, was built in the 1970s for $2,250,000.[30] Unit 24E and Unit 25 in total had a capacity of 352 people, and they had a total cost of $1,750,000.[30] The total construction cost of all of Unit 24, constructed in 1975, is $3.6 million. The unit had 192 single cell medium security beds. The facility has two stories and three housing zones, each having 64 beds. Zones A and B housed special needs prisoners who were receiving mental health care. Zone C had general population A and B security level prisoners.[32]

- Unit 27

- In the 1990s, Unit 27 was the protective custody facility. Richard Rubin, author of Confederacy of Silence: A True Tale of the New Old South, noticed that most of the prisoners in Unit 27 were White, while overall in MSP most prisoners were Black.[64]

- Unit 28

- In the mid-2000s, Unit 28 was the facility for the A&D Treatment Program for Special Needs program, which is for prisoners with HIV/AIDS who are more than 7 months and within 30 months of their release dates. The program began as a therapeutic community in April 2002; previously the program was a 12-week program.[71] Historically Unit 28 was the housing where HIV positive offenders were segregated into.[98] In 2010 MDOC Commissioner Chris Epps said that MDOC, beginning in May, would no longer segregate HIV offenders.[99] By August 2010 Unit 28, which had 192 beds, closed.[100]

- The $41 million unit opened in August 1990, increasing MSP's maximum security bed space by over 15 percent; during that year Mississippi officials said that the prison needed more maximum security space after Unit 32's opening.[82] Prior to Unit 32's opening, MSP had 56 "lockdown" cells for difficult prisoners.[11] By 2003, the American Civil Liberties Union filed a lawsuit on behalf of six inmates, alleging poor conditions in Unit 32's death row.[101] In 2007 three inmates in Unit 32 were murdered by other inmates in a several month span.[102] During that year a guard at Unit 32 said that under-staffing contributed to the security lapses.[102] In 2010 MDOC and the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) reached an agreement to close Unit 32 and transfer prisoners to other areas. Mentally ill prisoners in the unit will be transferred to the East Mississippi Correctional Facility near Meridian, Mississippi.[103]

Guard Row

edit"Guard Row" is the area where employees of MSP and their dependents live.[104] As of the 1970s "Guard Row", a nickname for the main road that bisects the prison, has identical wood frame houses, most of which had been built in the 1930s by the Work Projects Administration. Around 1971, the state charged employees a rent of 10 to 20 dollars (about $75.23-150.47 adjusted for inflation) per month, a rate described by Donald Cabana, a former superintendent of MSP, as "nominal". The state provided housing for employees due to the isolation of MSP, and therefore the staff can quickly respond to emergencies such as inmate disturbances or escapes. As of the 1970s, multiple generations of families lived and worked at MSP.[105]

As of 2002, the internal audit building, is on Guard Row.[106]

Education

editThe Sunflower County Consolidated School District serves children of employees residing on the grounds of Parchman. Students are zoned to A. W. James Elementary School in Drew for elementary, Drew Hunter Middle School in Drew,[107] and Thomas E. Edwards Sr. High School (formerly Ruleville Central High School) in Ruleville. Residents were previously zoned to the Drew School District,[108] and children who lived on the grounds of MSP attended A.W. James Elementary School and Drew Hunter High School in Drew. [109] Prior to the 2010–11 school year the Drew School District secondary schools were Hunter Middle School and Drew High School. On July 1, 2012, the Drew School District consolidated into the Sunflower district, and the high school division of Drew Hunter closed as of that date, with high school students rezoned to Ruleville Central.[110]

In 1969, the State of Mississippi passed a law written by Ruleville-based state senator Robert L. Crook that allowed Parchman employees to use up to $60 ($498.51 when adjusted for inflation) every month to pay for educational costs for their children. As a result some Parchman employees sent their children to North Sunflower Academy, and the State of Mississippi used general support funds to pay for some of North Sunflower Academy's transportation costs, including school buses, bus drivers, and gasoline. According to a Delta Democrat Times article (circa November 1974), the State of Mississippi spent over $250,000 ($1544534.41 when adjusted for inflation) in tuition costs and thousands of dollars in transportation costs for North Sunflower. By that time nobody had legally challenged that law in court. Constance Curry, author of Silver Rights, stated it was legal under Mississippi law but may have been unconstitutional under U.S. federal law.[111]

Parchman, along with other areas in Sunflower County, is within the service area of the Mississippi Delta Community College (MDCC).[112] MDCC has the Drew Center in Drew,[113] while its main campus is in Moorhead.[114] Sunflower County Library System operates the Drew Public Library in Drew.[115]

Cemeteries

editParchman also has three cemeteries; prisoners are buried on-site.[116] A dead prisoner may be buried in one of two of the cemeteries.[117] Hundreds of prisoners had been buried at two of the cemeteries.[118]

Other facilities

editThe prison has a Visitation Center,[119] which serves as a point of entry and as a security checkpoint for visitors to MSP. After security screening, visitors depart the visitation center in buses bound for the specific units.[85]

The Mississippi State Penitentiary Training Academy and the Thomas O. "Pete" Wilson Adult Basic Education (ABE) facility are located on the MSP grounds.[120] "The Place", a restaurant, is also on the prison property.[121] Parchman has the Rodeo Arena, a venue for a prison rodeo.[122] The Mississippi State Penitentiary POTW (Publicly owned treatment works) numbers one and two are the institution's sewage treatment plants.[123]

The United States Postal Service operates the Parchman Post Office along Parchman Road 12/Mississippi Highway 32 inside the prison property.[124] Mississippi State Penitentiary has a dedicated fire department,[52] (MSP Fire Department[125]) a wastewater treatment plant, road crews, utility crews, a grocery store, and a hospital.[52] The fire department, which utilizes prisoners as firefighters, responds outside of the prison boundaries.[citation needed]

Parchman contains the superintendent's guest house, used to accommodate guests. As part of a longstanding agreement, the Governor of Mississippi stayed in the house once annually before conducting an inspection of the prison.[126]

History of composition

editWhen the prison farm was first established, forests were cleared and land was put into cultivation. Prisoners "deadened" or circled the trees. A sawmill opened, and the wood was converted into planks used to build the housing in the prison. In 1911 what was then "Parchman Place" had ten camps, with each camp holding over 100 prisoners and working on 100 acres (40 ha). The central buildings, including the superintendent's residence, the offices, a hospital with a capacity for 70 patients, the general store, the sawmill, and the brick and tile works, were placed in a location referred to as "Parchman". The post office was located along a railroad. Each camp had a telephone system that was headquartered in the "Parchman" location.[9]

By 1906, the state sent the healthy, young black males incarcerated in the Mississippi penal system to MSP and to the Belmont Farm. Other population groups in the Mississippi penal system went to other farms; White men went to the Rankin Farm in Rankin County, and all women went to the Oakley Farm in Hinds County.[12] By the early 1900s the majority of incarcerated felons in the State of Mississippi were sent to Parchman.[127] Around 1911, prisoners who developed chronic illnesses were sent from MSP to the Oakley prison.[9] In 1917 the Parchman property had been fully cleared, and the administration divided the facility into a series of camps, housing black and white prisoners of both genders.[13] By that year MSP had 12 male prison camps and one female prison camp. Throughout much of the prison's history, the prison authorities decided not to build fences and walls because the MSP property had a large size and a remote location.[8]

David Oshinsky, author of Worse Than Slavery, said that in the early 20th century Parchman, from the outside, "looked like a typical Delta plantation, with cattle barns, vegetable gardens, mules dotting the landscape, and cotton rows stretching for miles."[127] Alan Lomax, a folklorist, wrote in The Land Where Blues Began that "Only a few strands of barbed wire marked the boundary between the Parchman State Penitentiary and the so-called free world. Yet every Delta black knew he could easily find himself on the wrong side of that fence."[127] Camp One became the administrative and commercial center of Parchman. It was located near the main gate, the railroad depot, and the main road. William B. Taylor and Tyler H. Fletcher, authors of Profits from convict labor: Reality or myth observations in Mississippi: 1907–1934, said that Camp One, by 1917, appeared like "a little city."[13] Camp One housed the residences of the superintendent and the superintendent's staff, the residences of the camp sergeant and the two assistants of the sergeant, a hospital, a gin, a church, a post office, and a visitor's building.[13] The facility, known as the "front camp", also housed an administration building and an infirmary described by Oshinsky as "crude". Newly arriving prisoners were processed at the administration building, and they received their prison uniforms there.[127] Taylor and Fletcher said that the other camps "amounted to little more than wooden barracks surrounded by cultivated land."[13] Within Parchman, the camps other than Camp One shared 15,000 acres (6,100 ha) of land.[13]

In the 1930s, the female camp, mostly African-American,[128] was isolated from the male camps. An enclave within the camp was reserved for white inmates.[129]

Around 1968, Camp B was one of the largest African-American camps of MSP.[130] Camp B was located in unincorporated Quitman County, near Lambert, away from the main Parchman complex.[131] Camp B's buildings have been demolished.[132] Until the post-lawsuit units opened in the 1970s, Parchman's newest unit was the first offender camp, a red brick building that opened in the 1960s. The building had a fence, two guard towers at opposite corners, and a gateshack. Donald Cabana, who became the prison's superintendent and executioner, said that the building was "not physically impressive."[133]

Around 1971, most areas of the prison had no guard towers, no cell blocks, no tiers, and no high walls. Cabana said that the prison was "a throwback to another time and place". Cabana described the employee housing as "by and large drab and in various states of disrepair."[105] During that time Camp 16 served as the Maximum Security Unit (MSU); the building was surrounded by double fences with concertina wire, and gun towers were located at the four corners of the building. MSU housed death row inmates and inmates put under maximum security, and the camp housed the gas chamber. MSP staff called the building "Little Alcatraz". Cabana, a native of Massachusetts, said that Camp 16 was the only building that resembled the northern U.S. penitentiary that he was familiar with.[105] Around that year MSP had around 2,000 men and less than 100 women in its camps. Most camps were "work camps", which had a quota of acreage to maintain. Some had special functions; for instance the "disability" camp did the laundry, and the "front camp" housed prisoners who worked in the administration building; those inmates worked as clerks, janitors, and maintenance personnel.[53] Each camp usually had no more than 100-200 prisoners. Because the prison population was spread across many units, the population would have difficulty engineering major disturbances. Cabana cited this example to say "In some respects, Parchman was a penologist's dream."[134]

After the 1972 Gates v. Collier federal judge ruling,[11][30] the State of Mississippi replaced its previous inmate housing units, called "cages", with barracks buildings surrounded by barbed wire-topped fences. John Buntin of Governing Magazine said that the new units were "hastily built."[11] Several MSP units were built in the 1970s; 3,080 beds were added for a total cost of $25,345,000.[30] In the 1980s, Mississippi State Penitentiary had 21 scattered camps.[29] In 1983, Camp 25 served as the female unit, and the unit had no parking facilities.[135] After Central Mississippi Correctional Facility opened, the women were moved out of Camp 25.[136] In the 1990s, MSP had 6,800 prisoners;[137] in 1990 Mississippi had a population of 2,573,216, so about .026% of Mississippi's population was incarcerated in MSP at that time.[138] The prison population had been increasing rapidly over the decade leading to 1995, and the prison officials converted a gymnasium into inmate housing and still faced overcrowding. Many construction projects occurred during that time.[137]

In the early 2000s, MSP had five areas. Area I had Unit 29. Area II had units 12, 15-B, 20-, 25–26, and 30. Area III had units 4, 10, 17, 20, 22–24, 27–28, 31, and 42. Area IV had Unit 32. Area V had Central Security. At that time 18 units housed prisoners, with the 1,488-bed Unit 29 being the largest unit in terms of prisoner capacity and the 60-bed Unit 17 being the smallest. At that time the prison's capacity was 5,631.[139] The Internal Audit building, located along Guard Row, was destroyed in a fire in 2002.[125] In the mid-2000s MSP had three areas. Area I had Units 15 and 29 and the Front Vocational School. Area II had units 25–26, 28, 3031, and 42. Area III had units 4 and 32. At the time, 10 units housed the 4,700 prisoners in the facility, with the 1,568 bed Unit 29 being the largest unit and the 54-bed Unit 42 (the hospital unit) being the smallest. At that time, the prison's capacity was 4,840.[140]

Weather

editKaren Feldscher of the Northeastern University Alumni Magazine said that in the region around MSP routinely had humid summers of 90 or more degrees Fahrenheit with mosquitoes present, while the winters "are brown and stark."[66]

| Climate data for Parchman | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Mean daily maximum °F (°C) | 49 (9) |

55 (13) |

64 (18) |

73 (23) |

82 (28) |

89 (32) |

92 (33) |

92 (33) |

86 (30) |

76 (24) |

64 (18) |

53 (12) |

73 (23) |

| Mean daily minimum °F (°C) | 31 (−1) |

34 (1) |

43 (6) |

51 (11) |

61 (16) |

69 (21) |

72 (22) |

70 (21) |

63 (17) |

51 (11) |

42 (6) |

35 (2) |

52 (11) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 5.25 (133) |

4.37 (111) |

5.47 (139) |

5.25 (133) |

5.07 (129) |

4.83 (123) |

3.18 (81) |

1.54 (39) |

2.63 (67) |

2.58 (66) |

5.80 (147) |

5.00 (127) |

50.97 (1,295) |

| Source: Weather.com[141] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

editAs of September 1, 2008, Mississippi State Penitentiary, with a capacity of 4,527, had 4,181 prisoners, comprising a total of 29.04% of people within the Mississippi Department of Corrections-operated prisons, county jails, and community work centers.[142] Of the male inmates at MSP, 3,024 were black, 1,119 were white, 30 Hispanic, six were Asian, and one was Native American. As of 2008, there was one African-American woman confined at MSP.[143] As of November 8, 2010, Parchman had about 998 free employees.[3]

In 1917, 90% of Parchman's prisoners were black. Most of the black prisoners were serving long sentences for violent crimes against other blacks and were illiterate laborers and farm workers. Of the black prisoners who committed crimes against other blacks, 58% had sentences of ten years or more and 38% had life sentences. Of the black prisoners who committed crimes against other blacks, 35% had committed murder, 17% had committed manslaughter, 8% had committed assault and battery, and 5% had committed rape or attempted rape.[127]

In 1937, the Parchman community had 250 residents, while the prison held 1,989 inmates.[144] In 1971, the prison employed fewer than 75 free employees because trusties performed many tasks at Parchman. The free employees included administrative, medical, and support employees.[145]

Prisoner life

editLocated on fertile Mississippi Delta land, Parchman served as a working farm. Inmate labor was used for many tasks from raising cotton and other farm food products, to building railroads and extracting turpentine gum from pine trees. Parchman, then as now, was in prime cotton-growing country. Inmates labored there in the fields raising cotton, soybeans and other cash crops, and produced livestock, swine, poultry and milk.[146] Inmates spent much of their time working with crops except the period from mid-November to mid-February, because the weather was too cold for farm work. Donald Cabana, who previously served as a superintendent and an executioner at Parchman, said that the labor situation was an advantage to the prison because inmates were occupied with it.[147] Cabana added that "idleness" was an issue facing many other prisons.[148]

Throughout MSP's history, most prisoners have worked in the fields.[66] Historically, prisoners worked for ten hours per day, six days per week. In previous eras prisoners lived in long, single-story buildings made of bricks and lumber produced on-site; the inmate housing units were often called "cages". Prison officials selected prisoners they deemed trustworthy and made them into armed guards; the prisoners were named "trustee guards" and "trustee shooters". Most male inmates did farm labor; others worked in the brickyard, cotton gin, prison hospital, and sawmill.[8] Women worked in the sewing room, making clothes, bed sheets, and mattresses. They also canned vegetables and ran the laundry.[149] On Sundays prisoners attended religious services and participated in baseball games, with teams formed on the basis of the camps.[8]

Throughout its history, Parchman Farm had a reputation of being one of the toughest prisons in the United States. This reputation antedated the 1960s arrival of the Freedom Riders.[150] Cabana said "A life sentence in Parchman is an eternity."[151]

Historically, most male prisoners wore "ring arounds", consisting of trousers and shirts with horizontal black and white stripes.[127] Female prisoners wore "up and downs", which were baggy dresses with vertical stripes.[152] "Trustee shooters" wore vertical stripes.[153]

In the 1930s, most of the crops planted at Parchman were cotton. The facility's brickyard, factories, gin, and machine shop gained the State of Mississippi profits. For most of the day, the female prisoners sewed utilitarian cloth goods, including bedding, curtains, and uniforms for the institution. When sewing labor was not available, women chopped cotton.[128]

For a period in Parchman's history, women lived in Camp 13. Male sergeants and male trusties guarded the women. As a result, sexual intercourse and rape occurred in the women's unit. Women lived in large dormitories.[149] White women usually numbered between zero and five, black women usually numbered 25 to 65. White female prisoners lived in a small brick building, while African-American prisoners lived in what David Oshinsky, author of Worse than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice called a "large shed-like building", with a fence separating the two buildings.[154]

Cabana said that in 1971 the prison environment was "relatively tranquil" because many prisoners worked outside instead of being confined in their cells for long periods of time.[148] The prison was still segregated in the 1970s. Around that time a black leather strap named "Black Annie" was used to punish prisoners who broke rules. Other prisoners who broke rules were forced to stand for hours at a time on up-ended soda crates. During the era, stronger prisoners attacked and raped weaker prisoners, and prison staff provided little to no intervention in these incidents. Some inmates worked as "houseboys", maintaining the residences of prison officials. Some prisoners were allowed to leave the prison grounds to pick up supplies and transport them back to MSP. Karen Feldscher of Northeastern Alumni Magazine stated that the trustee guard system often produced "disastrous results."[66] Cabana said that the trustee system "apparently worked quite well, as there were seldom any disciplinary problems among the shooters". Because trustees performed many tasks, the prison employed relatively few free employees.[145] Because of the scenario, Cabana said that the prisoners were the people who carried guns and enforced rules, while in Massachusetts the prison guards carried the guns and enforced rules.[155]

In the 1960s, shortly after inmates arrived at Parchman, they received nicknames that reflected personality traits and physical characteristics. For instance, a man named Johnny Lee Thomas was nicknamed "Have Mercy" when he protested a beating of a fellow inmate. Thomas stated that Parchman was, in the words of William Ferris, author of Give My Poor Heart Ease, "a world of fear in which only the strong and intelligent survive". Ferris added that "Like the trickster rabbit, the black prisoner had to move quicker and think faster than his white boss."[130]

After the Gates decision, the number of murders of prisoners dropped overall. When integration came, prisoners formed gangs based on race to protect one another. In addition, the prison gangs gained the power that trustee shooters had held. In 1990, the prison emergency room treated 1,136 incidents of prisoner on employee assaults and 1,169 prisoner on prisoner assaults.[156]

Musical traditions

editWhile living at MSP, many African-American inmates sang work chants, a tradition traced to West Africa.[130] Work chants were used by farm laborers to pace their work.[157] While inmates worked, a leader called the chant, with other inmates following him. One song includes a story of an inmate swimming through the Sunflower River to confuse bloodhounds, verses showcasing prisoners who return hoes to their commanding captain and refuse to continue working, and a story of a beautiful woman named Rosie who waits outside the prison boundary.[130] William Ferris, author of Give My Poor Heart Ease, said that "for all of these inmates, music was a means to survive within the prison's grim world."[158] The Mississippi Blues Trail added Parchman to its list of sites at 10 AM on Tuesday September 28, 2010; Parchman received the trail's 113th historical marker.[159]

Folk song collectors John and Alan Lomax visited Parchman Farm in 1933, during a recording trip across the Southern states of the US. Lomax wrote that they recorded a prisoner singing:

Ask my cap'n, how could he stand to see me cry

He said you low down nigger, I can stand to see you die

Reflecting on the significance of the singing he had heard in Parchman, Alan Lomax later wrote:

I had to face that here were the people that everyone else regarded as the dregs of society, dangerous human beings, brutalized and from them came the music which I thought was the finest thing I'd ever hear coming out of my country. They made Walt Whitman look like a child. They made Carl Sandburg, who sang these songs, look like a bloody amateur. These people were poetic and musical and they had something terribly important to say.[160]

In 2023, music producer Ian Brennan recorded inmates singing in the prison chapel and released the recordings under the name Parchman Prison Prayer.[161]

Conjugal visits

editHistorically, Mississippi State Penitentiary permitted imprisoned men to engage in conjugal visits with wives; conjugal visits had to be with married, opposite-sex couples. The Mississippi Department of Corrections (MDOC) did not include couples of common-law marriages in its definition of marriage that makes a couple eligible for conjugal visits. MSP prisoners of "A" and "B" custody levels were permitted to engage in conjugal visits if they had no rule violation reports in the previous six months leading to each conjugal visit.[68] According to the decision of Chris Epps, the MDOC commissioner, the entire Mississippi state prison system ended conjugal visits in February 2014. Epps stated that the possibility of creating single parents and the expenses were the reasons why conjugal visits ended.[162]

Formal records stating when conjugal visits began at MSP do not exist; Mississippi was the first state to allow conjugal visits to take place in its prisons.[163] Columbus B. Hopper, author of The Evolution of Conjugal Visiting in Mississippi (1989), said, "In all probability, conjugal visiting began as soon as Parchman Plantation was made into a prison in 1900" and "I traced it back definitely as early as 1918."[164] There was no state control or legal status for conjugal visits. Originally only African-American men were allowed to participate, as society believed that the sexual drives of black men were stronger than those of white men.[165] Prison authorities believed that if black men were allowed to have sexual intercourse, they would be more productive in the farming industries of the prison. By the 1930s, the authorities had permitted white men to receive conjugal visits. As officials did not want pregnancies to occur in prison, at that time they did not permit female prisoners to have conjugal visits.[166] In the 1930s, on Sunday afternoons, prostitutes visited Parchman and the prison camps. Hopper said that a prisoner's song referred to a prostitute charging 50 cents for her services, "not a small amount during the Great Depression when many people worked a 12-hour day for a dollar."[164][167]

Originally, there were no facilities designated for conjugal visits. Some prisoners used tool sheds and storage areas in the camp areas, and others took their wives and girlfriends into the prisoner barracks and placed blankets over beds to allow for privacy.[164] In 1940 prisoners began building special houses to be used by prisoners and their families during conjugal visits.[168]

In 1962, Hopper, in The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science, said that the Mississippi State Penitentiary had the most liberal visitation program in the United States.[169] Rules of visitation and leave, adopted in 1944, allowed inmates to make home visits for reasons other than emergency. According to a 1956 survey, it was the only correctional facility in the country to do so. Inmates were allowed to be visited every Sunday for two hours by their wives. In 1962, each Parchman camp, with the exception of the maximum-security camps, housed a five to ten-room structure called a red house; each house is near the main gate of the main camp building.[170] In the house, the inmate and his wife may engage in sexual intercourse. Children are encouraged by the prison authorities to visit; as of 1962 one camp houses a play area for children. The Parchman conjugal visit program is designed so that all members of the family may interact with a particular prisoner.[169] In 1962, the prison officials said that the conjugal visits were an important factor in preserving marriages of inmates and reducing prison homosexuality. During that year, most inmates reported favorable opinions about the conjugal program.[171]

David Oshinsky said the statements regarding the preservation of marriages were "likely" to be correct and the statements regarding the prison sexuality were "probably" not true.[166] Penologists stated that factors that may have contributed to the development of the system were the strength of family ties in rural areas. Parchman was "primarily an agricultural plantation that is a self-contained, sociocultural system functioning much as a culture in and of itself",[172][page needed] the emphasis placed on agricultural production, and the small sizes of the camps. The guards in the camps knew the prisoners personally. Due to the lack of records, it was not possible to tell if the conjugal visit program reduced prison sexuality or recidivism.[173]

In the 1970s, Parchman still did not maintain records on the conjugal visits that took place at the facility.[168] In 1972 women at Parchman became eligible for conjugal visits. In 1974, prisoners of both sexes were permitted to have three-day, two-night family visits.[174] In the 1980s guards reported that inmates were more docile if they had periodic sexual access to their wives. Robert Cross of the Chicago Tribune reported in 1985 that the MSP program received relatively little attention compared to newer and more limited conjugal visit policies in California, Connecticut, New Mexico, New York, South Carolina, and Washington. Cross added that "The difference, perhaps, is that in Mississippi, where Parchman serves as the only penitentiary, nobody issued proclamations or opened up the matter for debate."[29] As of 1996, a newly established Parchman unit used conjugal visits as a reward in a behavioral modification program[168] and a typical married prisoner at Parchman had one conjugal visit every two weeks, and periodically used the family visits.[174]

Education

editIn 2005, a campus of the New Orleans Baptist Theological Seminary was established in the penitentiary. [175] [176]

The Parchman Animal Care & Training (PACT) program, which was established in April 2008, organizes inmate care of livestock.[177]

Literature

editParchman, a book by R. Kim Cushing, was published by the University Press of Mississippi. It includes stories written by 18 prisoners and multiple photographs. Reverend William Barnwell wrote in The Clarion-Ledger that the book was "beautifully laid out" and portrays the prisoners "as fellow human beings, with their own strengths and weaknesses, like the rest of us. They — and we — deserve such a book."[178]

In Our Own Words: Writing from Parchman Prison – Unit 30 and Unit 30 New Writings from Parchman Farm include stories written by inmates participating in a writing program at Unit 30. A total of 12 prisoners wrote content in the New Writings book, and four wrote content appearing in both books. The Mississippi Humanities Council gave a grant to the writing program, and the sales from the books also fund the writing program.[179]

In popular culture

editDavid Oshinsky said in 1996, "Throughout the American South, Parchman Farm is synonymous with punishment and brutality...the closest thing to slavery that survived the Civil War." This is quoted in 2014 Atlantic article "The Case for Reparations" by journalist Ta-Nehisi Coates.[180][181]

A character in William Faulkner's The Mansion referred to MSP as "destination doom."[16] John Buntin of Governing magazine said that MSP "has long cast its shadow over the Mississippi Delta, including my hometown of Greenville, Mississippi."[52]

The prison is the subject of a number of blues songs, most notably "Parchman Farm Blues" by Bukka White, and Mose Allison's "Parchman Farm", which was later covered by a number of other artists including Bobbie Gentry, John Mayall, Johnny Winter, Georgie Fame, Blue Cheer, and Blues Image.

In 1963, the Republican gubernatorial nominee Rubel Phillips made the penitentiary an issue in his unsuccessful campaign against the Democrat Paul B. Johnson Jr. Phillips called the institution at Parchman "a disgrace" and urged the establishment of a constitutional board "free of politics to exercise responsible leadership". Phillips recounted the case of inmate Kimble Berry, who served time for manslaughter who was granted leave in 1961 by acting Governor Johnson (while Governor Ross Barnett was out of state) but showed up in a Cadillac in Massachusetts claiming that he had been authorized to recover burglary loot.[182]

The prison also served as a major source of material for folklorists such as Alan and John Lomax, who visited numerous times to record work songs, field hollers, blues, and interviews with prisoners. The Lomaxes in part focused on Parchman at that time because it offered a particular closed society shut off from the outside world. John Lomax, accompanied by his wife Ruby, toured through the southern states recording blues work songs and other folk songs for the Library of Congress as part of a WPA project in 1939. They recorded work songs and chants while inmates were performing a group task, such as hoeing the fields at Parchman Farm as well as blues songs sung by inmate musicians.[183]

The Coen brothers' film, O Brother, Where Art Thou?, makes reference to Parchman, both directly and by including a song on the soundtrack that was recorded at Parchman in 1959 by Alan Lomax.

In William Faulkner's book Old Man, which was also published as part of the book The Wild Palms, the Tall and Fat Convicts were sent from Parchman to rescue folks from the 1927 Mississippi flood. In Faulkner's The Mansion, Mink Snopes was imprisoned in Parchman.

In August Wilson's play The Piano Lesson, the characters Boy Willie, Lymon, Doaker, and Wining Boy all served time at Parchman.

The stage play The Parchman Hour, by playwright Mike Wiley, is based on the following quote by a Freedom Rider imprisoned there in 1961:

Did you know that at Parchman, to pass the time and to keep our spirits up, we "invented" a radio program? I don't recall that we named it, but "The Parchman Hour" would have been a good name. Each cell had to contribute a short "act" (singing a song, telling a joke, reading from the Bible—the only book we were allowed) and in between acts we had "commercials" for the products we lived with every day, like the prison soap, the black-and-white striped skirts, the awful food, etc. We did this every evening, as I recall; it gave us something to do during the day, thinking up our cell's act for the evening.

— Mimi Real, Freedom Rider, 1961[184]

The play premiered professionally at PlayMakers Repertory Company in 2011. In 2013, it was produced for the second time at the Cape Fear Regional Theatre in Fayetteville, North Carolina, once again directed by Mike Wiley.[citation needed]

The Chamber (1993), a best-selling novel by John Grisham, is set at Parchman's Death Row.[185][186] Many of Grisham's other novels make reference to the prison and in his book, Ford County, the short story "Fetching Raymond" takes place in large part at Parchman. The Chamber, the movie based on the novel, starring Gene Hackman and Chris O'Donnell, was filmed at the penitentiary.[187]

The 1999 film Life, portraying a group of bootleggers from New York who are falsely convicted of murder and are given life sentences, takes place at Parchman. While it is set in Mississippi, filming occurred in California.[188]

In Jesmyn Ward's Sing, Unburied, Sing, a young boy killed at Parchman Prison comes back to haunt the narrator, Jojo, and his family; nevertheless, they drive upstate to pick-up Michael, the father, who is just freed from the same prison.

Parchman is mentioned and shown several times in In the Heat of the Night. Parchman appears as a plot element in "A Trip Upstate", where Sparta's police chief, Bill Gillespie, visits a death row inmate and witnesses the inmate's execution.[189]

Quotation

editOh listen you men, I don't mean no harm

If you wanna do good, you better stay off old Parchman Farm

We got to work in the mornin', just at dawn of day

Just at the settin' of the sun, that's when the work is done— Bukka White, "Parchman Farm Blues"

Notable people

editInmates

editDeath row prisoners

editCurrent

edit- Richard Gerald Jordan

- Willie Cory Godbolt, perpetrator of the 2017 Mississippi shootings

Former

edit- Cory Maye[190][191] (Unit 32;[192] released in 2011)

- Curtis Flowers (previous, conviction vacated in 2019)

Executed

edit- Jimmy Lee Gray (executed 1983)

- Edward Earl Johnson (executed 1987)

- John B. Nixon (executed 2005)

- Earl Wesley Berry (executed 2008)

- David Neal Cox (executed 2021)

- Thomas Edwin Loden Jr. (executed 2022)

Other prisoners

edit- Samuel Bowers (died in the hospital unit)[193][194]

- Stokely Carmichael[195]

- James Farmer[195]

- Son House[196]

- Edgar Ray Killen (Unit 31)[197]

- John Lewis[198]

- Vernon Elvis Presley

- Carol Ruth Silver[199]

- Bukka White[196]

- Luke Woodham, perpetrator of the 1997 Pearl High School shooting[200]

- Thomas A Tarrants III[201][202][203]

Staff

edit- Chris Epps, a guard in Unit 29, was promoted within the department, and was appointed as Deputy Superintendent of Parchman in 1998. In 2002 he was appointed as Commissioner of MDOC.[204] In 2014, he was indicted on federal charges for bribery and corruption. On May 25, 2017, he was given a federal prison sentence of 235 months (19.6 years).[citation needed]

See also

editReferences

edit- Arsenault, Raymond (2006). Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cabana, Donald (1996). Death at Midnight: The Confession of an Executioner. Northeastern University Press.

- Fankhauser, David. Freedom Rides - Recollections by David Fankhauser. Clc.uc.edu. Accessed March 21, 2024.

- Farmer, James (1998). Lay Bare the Heart: An Autobiography of the Civil Rights Movement. Texas Christian University Press.

- Hopper, Columbus B. (September 1962). "The Conjugal Visit at Mississippi State Penitentiary". The Journal of Criminal Law, Criminology, and Police Science. 53 (3): 340–343. doi:10.2307/1141470. JSTOR 1141470.

- Hopper, Columbus B. (April 1989). "The Evolution of Conjugal Visiting in Mississippi". The Prison Journal. 69 (1): 103–109. doi:10.1177/003288558906900113. S2CID 143626172. Available at SAGE Journals; ISSN 0032-8855

- Jay-Z, Yo Gotti help 150 inmates at Mississippi prison sue over "barbaric" conditions, nbcnews.com. Accessed March 21, 2024.

Footnotes

edit- ^ "Parchman, Mississippi". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b "Mississippi State Penitentiary". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey, United States Department of the Interior.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "State Prisons" Archived 2002-12-06 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved January 14, 2011.

- ^ a b "MDOC Quick Reference". Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- ^ "Mississippi State Penitentiary". Mississippi Department of Corrections. July 10, 2013. Archived from the original on December 6, 2002.

- ^ a b c "A Brief History of the Mississippi Department of Corrections" Archived 2010-08-19 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved September 18, 2010.

- ^ a b Yardley, Jonathan. "In the Fields of Despair", The Washington Post, March 31, 1996. Retrieved March 1, 2011. "The eventual replacement for convict leasing was Parchman Farm, a 20,000-acre tract in the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta, 90 miles south of Memphis at a dilapidated railroad spur known as Gordon Station."

- ^ a b c d e f "Mississippi State Penitentiary (Parchman) Photo Collections" Archived 2010-08-12 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Archives and History. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Article 14 -- No Title": "Convicts Who Are In Demand After Serving Terms". (Direct article link) The New York Times. Retrieved August 14, 2010.

- ^ a b c Cabana, Donald A. "The History of Capital Punishment in Mississippi: An Overview" Archived 2010-10-07 at the Wayback Machine, Mississippi History Now,Mississippi Historical Society. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Buntin, John. "Mississippi's Corrections Reform" Archived 2010-08-15 at the Wayback Machine, Governing Magazine, August 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Taylor, William B. and Tyler H. Fletcher. "Profits from convict labor: Reality or myth observations in Mississippi: 1907–1934", Journal of Police and Criminal Psychology, Volume 5, No. 1. Page 30 (1/9). Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g Taylor and Fletcher, "Reality or myth", p. 31

- ^ Federal Writers' Project of the Works Progress Administration, Mississippi: A Guide to the Magnolia State. The Viking Press, New York, May 1938. 408. Retrieved from Google Books on July 20, 2010. ISBN 978-1603540230.

- ^ a b c "The Death Penalty In Mississippi, Executions" Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved April 9, 2022.

- ^ a b c Arsenault, Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. Oxford University Press, 2006. 325. Retrieved from Google Books on August 13, 2010. ISBN 978-0195136746.

- ^ Arsenault, Raymond (2006). Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 225.

- ^ Farmer, James (1998). Lay Bare the Heart: An Autobiography of the Civil Rights Movement. Texas Christian University Press. p. 22.

- ^ Farmer (1998). Lay Bare the Heart. p. 23.

- ^ a b c d Fankhauser, David. Biology.clc.uc.edu "Freedom Rides" Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Oshinsky, David M. (1997). Worse Than Slavery: Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice. Free Press. p. 235.

- ^ Biology.clc.uc.edu Archived 2013-10-21 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Klinkenberg, Jeff (March 3, 2006). "Courage and Convictions". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved April 7, 2011 – via St. Petersburg Times.

- ^ "ACLU Parchman Prison". Archived from the original on March 7, 2008. Retrieved August 29, 2006.

- ^ "Parchman Farm and the Ordeal of Jim Crow Justice". Retrieved August 28, 2006.

- ^ Ted Gioia (2006). Work Songs. Oxford University Press. p. 201. ISBN 978-0822337263. Retrieved December 8, 2007.

judge william c keady.

- ^ "Mississippi Urged to Revamp Prison; Panel Proposes Eliminating Farm-for-Profit System". The New York Times, October 8, 1972, p. 8, Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "Arrests hint at new effort on prison scams", The Advocate. September 20, 1989. Retrieved from the Google News search on February 28, 2011. "In the mid-1980s, an army of Mississippi authorities and postal inspectors descended on the Parchman prison to stamp out a large scam involving forged money orders.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Cross, Robert. "A prison's family plan". Chicago Tribune. October 2, 1985. Page D1. Retrieved September 23, 2010. "Ten miles east of Shelby, the sprightly cotton fields along Miss. Hwy. 32 begin to recede, and parched weeds on the shoulder squeeze the road down to a single lane of potholes. Highway 32 continues for a few more yards. Then a steel barricade, flanked by a guard tower, cuts it off." and "Now the inmate count at Parchman hovers just above 4000 including 200 women in a couple of camps..."

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "A Brief History of the Mississippi Department of Corrections" Archived 2010-08-19 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved July 21, 2010.

- ^ Dow, David R. and Mark Dow. Machinery of Death: The Reality of America's Death Penalty Regime. Routledge, 2002. 102. Retrieved July 21, 2010; ISBN 978-0415932677.

- ^ a b "MDOC Reveals Findings of Mississippi State Prison Escape" Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections, 17 November 2003. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Mississippi State Prison Visitation Cancelled" Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. November 17, 2003. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ ""Mississippi Inmate Escapee Larry Hentz Captured In San Diego" Archived 2011-09-27 at the Wayback Machine, Mississippi Department of Corrections, December 11, 2003. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Delta market sees boost from industrial, retail successes: space still available, though", Mississippi Business Journal, July 25, 2005. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ a b "State Prison Uses Technology to Block Inmates' Calls" Archived 2011-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. JXNTV. September 8, 2010. Retrieved September 14, 2010.

- ^ "Putting an end to illegal cell phone use in prisons" (PDF). fcc.gov. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ "Mississippi cut corrections by $215M. Horrid conditions, violent deaths have followed at Parchman". February 18, 2020.

- ^ "2019 Health Inspection Annual Report". msdh.ms.gov. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ a b "Inspection Report 2020" (PDF). msdh.ms.gov. Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ Bouie, Jamelle (January 31, 2020). "Opinion | 12 Deaths in Mississippi Tell a Grim Story". The New York Times.

- ^ Norman, Greg (January 21, 2020). "Three more inmates die at troubled Mississippi prison". Fox News. Retrieved January 21, 2020.

- ^ "MDOC head Pelicia Hall resigns as head of troubled state prison system".

- ^ Vera, Amir (January 22, 2020). "Another inmate has died at Mississippi's Parchman prison, making 8 deaths at the facility this year". CNN. Retrieved January 24, 2020.

- ^ a b McLaughlin, Elliott C. (January 15, 2020). "Mississippi scrambles to find cells for 625 violent inmates after Parchman prison unit deemed unsafe". CNN.

- ^ "2021 Health and Sanitation Inspection Report". Retrieved August 1, 2023.

- ^ Ortiz, Erik (February 26, 2020). "Jay-Z, Yo Gotti Help 150 Inmates at Mississippi Prison Sue Over 'Barbaric' Conditions". NBC News.

- ^ "15 dead in six weeks. Can a federal investigation fix the grim legacy of Mississippi's prisons?". The Washington Post. February 6, 2020.

- ^ Gallant, Jacob (April 20, 2022). "'Years of deliberate indifference': Justice Dept. says conditions at Parchman violate Constitution". WLBT. Retrieved April 20, 2022.

- ^ "2020 Census – Census Block Map: Sunflower County, MS" (PDF). Suitland, Maryland: U.S. Census Bureau. pp. 1-2 (PDF pp. 2-3/22). Retrieved August 12, 2022.

Mississippi State Penitentary [sic]

- ^ a b c d "Media Kit Joseph D. Burns Archived 2013-10-04 at the Wayback Machine." Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e Buntin, John. "Down on Parchman Farm" Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine. Governing Magazine. July 27, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ a b c Cabana, Donald. Death at Midnight: The Confession of an Executioner. University Press of New England, 1998. 39. Retrieved from Google News on August 16, 2010. ISBN 978-1555533564.

- ^ a b c Cheseborough, Steve, Blues Traveling: The Holy Sites of Delta Blues. University Press of Mississippi, 2004. 92. Retrieved from Google Books on September 29, 2010. ISBN 978-1578066506.

- ^ "Mississippi Department of Corrections, Parchman". Mississippi Department of Environmental Quality. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ "Parchman Farm". (Downloadable Map) Mississippi Blues Commission. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ Cheseborough, Steve, Blues Traveling: The Holy Sites of Delta Blues. University Press of Mississippi, 2004. 93. Retrieved from Google Books on September 29, 2010. ISBN 978-1578066506.

- ^ "'Back Gate' once used for contraband at Parchman will be reopened". WLBT-TV. October 14, 2020. Retrieved September 3, 2024.

- ^ "26 km NE of Cleveland, Mississippi, United States 7/1/1976". U.S. Geological Survey. Retrieved September 23, 2010.

- ^ Moye, J. Todd. Let the People Decide: Black Freedom and White Resistance Movements in Sunflower County, Mississippi, 1945-1986. University of North Carolina Press, November 29, 2004. 28. Retrieved from Google Books on February 26, 2012. ISBN 978-0807855614.

- ^ "Tornado Damages Mississippi Homes". Associated Press at the Daily Union. Sunday November 27, 1988. Page 4. Retrieved from Google News (3 of 20) on July 4, 2011.

- ^ "Cedric Chatterley: Photographs of Honeyboy Edwards, 1991–1996" Archived 2011-03-05 at the Wayback Machine. Duke University. Retrieved November 28, 2010. "Parchman Farm – Mississippi State Penitentiary, south of Tutwiler, Mississippi, July, 1992".

- ^ Merten, Charles J. "Mississippi, 1966 The struggle for civil rights". Oregon State Bar. 2003. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- ^ a b c d Rubin, Richard. Confederacy of Silence: A True Tale of the New Old South. Simon & Schuster, 2002. 321. Retrieved from Google Books on July 20, 2010. ISBN 978-0671036669.

- ^ Rubin, Richard. Confederacy of Silence: A True Tale of the New Old South. Simon & Schuster, 2002. 317. Retrieved from Google Books on July 20, 2010. ISBN 978-0671036669.

- ^ a b c d Feldscher, Karen. "The Warden". Northeastern Alumni Magazine. September 2004. Retrieved August 12, 2010. Archived May 26, 2010, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Anderson, Jack. "Conditions Inside Many Prisons In U.S. Dehumanizing, Perilous". The Toledo Blade. March 13, 1977. Page B5. Retrieved from Google News on July 20, 2010.

- ^ a b "Conjugal Visits" Archived 2010-08-01 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ a b "Locking Down on Illegal Cell Phone Traffic". (Archive) Mississippi Department of Corrections. 2 (2/31). Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ a b "Mississippi State Penitentiary". (2000-03.pdf) (Archive) Mississippi Department of Corrections. 10 (3/3). Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Mississippi Department of Corrections Alcohol and Drug Treatment Programs FY 2004 Annual Report" Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. Page 1. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ a b "Mississippi State Penitentiary, Unit 29". Dale And Associates. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ "Inmates Hurt in Prison Fight at Parchman". Sun Herald. June 15, 2000. Page A9 Local Front. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ "Mississippi State Penitentiary". Annual Report. Mississippi Department of Corrections. 2000. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Correctional". (Archive) Carrothers Construction. Retrieved April 28, 2012.

- ^ "Mississippi Department of Corrections receives $2.8 million grant from U.S. Department of Justice" Archived 2010-05-30 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. December 13, 2001. Retrieved January 25, 2011.

- ^ a b c "Treatment Programs Alcohol and Drug". Fiscal Year 2009 Annual Report Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. 59. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ Quinn, Paul. "Cummings moved to Parchman after testing positive for THC". University Wire. March 24, 2008. Retrieved July 20, 2010.

- ^ a b "Correctional" Archived 2011-07-08 at the Wayback Machine. Dale And Associates. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- ^ "The Resource" Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. Volume 7, Issue 6. June 2005. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ a b c "July 1, 1989–June 30, 1990 Annual Report" Archived March 8, 2012, at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. 9 (15/83). Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- ^ a b "Prison won't cure overcrowding". The Advocate. September 18, 1990. Retrieved August 9, 2010. "Hard-core Mississippi prisoners will be housed in a $41 million prison complex that opened last month, but the facility won't come close to providing room for all state inmates, officials say. The complex, called Unit 32, adds more than 15 times the current maximum-security bed space, but it's still not enough."

- ^ "George Bell III Transferred from Parchman" Archived 2012-03-06 at the Wayback Machine. WLBT. August 18, 2008. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ "Mississippi Department of Corrections' FY 2009 Cost Per Inmate Day" Archived 2010-07-13 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. December 8, 2009. 1/135. Retrieved July 27, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Visitation" Archived 2010-08-08 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved September 1, 2010.

- ^ "U32%20DR%20C%20Camp.jpg" Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved August 9, 2010.

- ^ Piasecki, Melissa. "Death Row Inmates and Mental Health". Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law. Retrieved July 19, 2010.

- ^ Crisp, Elizabeth. "Early release strategies produce empty prison beds". The Clarion-Ledger. October 1, 2011. Retrieved October 6, 2011.

- ^ Zhu, Alissa (January 7, 2020). "Parchman reopens notorious, long-closed Unit 32 after deadly Mississippi prison violence". Clarion Ledger. Retrieved May 19, 2021.

- ^ "Deaths of Two Inmates Announced by MDOC" Archived 2011-07-17 at the Wayback Machine. Mississippi Department of Corrections. Retrieved July 24, 2010. "State inmate Darlene Bruno #90842, a 63-year-old white female, was pronounced dead at 11:22 p.m. at the Mississippi State Penitentiary Hospital in Parchman on Sunday, September 8."