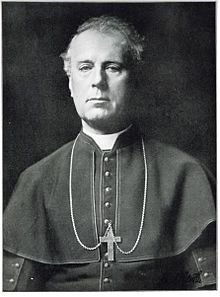

Patrick William Riordan (August 27, 1841 – December 27, 1914) was a Canadian-born American prelate of the Catholic Church who served as Archbishop of San Francisco from 1884 until his death in 1914. He served during the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, and he was a prominent figure in the first case submitted to the Permanent Court of Arbitration.

Patrick William Riordan | |

|---|---|

| Archbishop of San Francisco | |

| |

| Church | Catholic Church |

| Archdiocese | Archdiocese of San Francisco |

| Appointed | December 21, 1884 |

| Term ended | December 27, 1914 (his death) |

| Predecessor | Joseph Sadoc Alemany |

| Successor | Edward Joseph Hanna |

| Other post(s) | Coadjutor Archbishop of San Francisco (1883–1884) |

| Orders | |

| Ordination | June 10, 1865 by Engelbert Sterckx |

| Consecration | September 16, 1883 by Patrick Feehan |

| Personal details | |

| Born | August 27, 1841 Chatham, New Brunswick, Canada |

| Died | December 27, 1914 (aged 73) San Francisco, California, U.S. |

| Signature | |

Early life

editPatrick Riordan was born in Chatham, New Brunswick, to Matthew and Mary (née Dunne) Riordan.[1] His parents were both natives of Ireland, his father from Kinsale, County Cork, and his mother from Stradbally, County Laois.[2] Soon after the birth of his sister Catherine in 1844, his parents returned to Ireland with their children and there his brother Dennis was born in 1846.[3] However, the family was soon compelled to flee Ireland due to the Great Famine; after a brief return to New Brunswick, they settled in Chicago, Illinois, in 1848.[4][5]

As a boy in Chicago, Riordan met John Ireland (the future Archbishop of Saint Paul), with whom he maintained a lifelong friendship.[6] The Riordan family were parishioners at St. Patrick's Church, where Patrick's uncle, Rev. Dennis Dunne, served as pastor as well as vicar general of the Archdiocese of Chicago.[7]

Education

editRiordan received his early education at the University of Saint Mary of the Lake, which functioned as a parochial school as well as seminary at the time.[7] In 1856, he was enrolled at the University of Notre Dame in South Bend, Indiana, where he remained for two years.[8] It was at Notre Dame that Riordan decided to become a priest, and he was sent to study at the Pontificio Collegio Urbano de Propaganda Fide in Rome in 1858.[1]

When the Pontifical North American College was opened in December 1859, Riordan was one of the first twelve students to enter the institution.[9] That group of twelve included Michael Corrigan, Robert Seton, and Reuben Parsons, with Edward McGlynn serving as their prefect. However, after falling ill with malaria,[5] Riordan was forced to withdraw from the North American College in August 1860 and sent to continue his studies at the colonial seminary in Paris, operated by the Holy Ghost Fathers.[10]

Riordan completed his philosophical studies at Paris in 1861 and then enrolled at the American College of Louvain in Belgium to complete his theological studies.[8] His brother Dennis would also study at Louvain and become a priest in 1869.[11]

Priesthood

editWhile in Belgium, Riordan was ordained a priest on June 10, 1865, by Cardinal Engelbert Sterckx.[12] He received a licentiate in theology from Louvain in 1866.[1] On his return to Chicago the same year, he was appointed to the faculty of the seminary department at the University of St. Mary of the Lake, first as professor of canon law and Church history before filling the chair of dogmatic theology.[5] In 1867, he baptized his newborn cousin, Finley Peter Dunne, who would become a well-known humorist and journalist; Dunne later remarked, "[Riordan] is a creditable member of the family. We need a few archbishops to keep up the average now that the Bill has come in."[13]

When the university was closed in 1868, Riordan was assigned to pastoral work, serving at St. Patrick's Church in Woodstock and later at St. Mary's Church in Joliet.[8] Meanwhile, the mental health of Chicago's Bishop James Duggan had begun to deteriorate and Rev. Dennis Dunne, Riordan's uncle, informed Rome of Duggan's instability.[14] In retaliation, the bishop suspended Dunne from his duties as the diocese's vicar general and pastor of St. Patrick's Church.[15] Following Dunne's death in December 1868,[16] Duggan's refusal to attend the funeral drew sharp criticism from Catholics across the city and he appointed Riordan as pastor of St. Patrick's "in order to make some reparation."[17] However, only four days later, the bishop rescinded Riordan's appointment after receiving reports that the priest "had spoken badly of him."[17]

Duggan was placed in a mental institution in 1869 and Bishop Thomas Foley was given charge of diocesan affairs. Riordan's brother Dennis would serve as Foley's secretary and chancellor of the diocese (1873–1881).[11] In June 1871, Foley named Patrick as pastor of St. James Church in Chicago.[5] Four months into his tenure, the Great Chicago Fire devastated the city but missed St. James. Bishop Foley sent Riordan and another Chicago priest, Rev. John McMullen, to travel across the United States and Canada to collect funds for the city's restoration.[18] This would unwittingly prepare Riordan for dealing with another disaster 35 years later in San Francisco.

As pastor of St. James, Riordan erected a new church building on Wabash Avenue to accommodate his growing congregation, laying the cornerstone in 1876 and dedicating the building in 1880.[8] His cousin, Rev. Patrick W. Dunne, later served as pastor of St. James (1911–1927) after beginning his priestly ministry at St. Mary's Church in Joliet, where Riordan had also served.[19] Riordan's construction of the new church caught the attention of several bishops, and in 1882 his name was included on a list of three candidates for Bishop of Charleston, South Carolina, being the preferred choice of Archbishop James Gibbons of Baltimore.[20] Although the Charleston appointment ultimately went to Henry P. Northrop, Riordan would receive his own appointment as a bishop the following year.

Archbishop of San Francisco

editOn July 17, 1883, Pope Leo XIII appointed Riordan to be coadjutor archbishop with the right of succession to Joseph Sadoc Alemany, the Archbishop of San Francisco, California.[12] He was also given the honorary title of titular archbishop of Cabasa.[12] He received his episcopal consecration on the following September 16 from Archbishop Patrick Feehan, with Bishops William George McCloskey and Silas Chatard serving as co-consecrators, at St. James in Chicago.[12]

Riordan arrived in San Francisco in November 1883 and began to relieve the elderly Archbishop Alemany of his administrative duties.[1] The following year, he and Alemany both attended the third Plenary Council of Baltimore from November 9 and December 7, 1884.[1] During the council, Riordan brought his brother as his theological consultant and chaired the committee overseeing the Bureau of Catholic Indian Missions.[20] Shortly after the conclusion of the council, Alemany resigned on December 21, 1884, and Riordan succeeded him as the second Archbishop of San Francisco.[12]

In 1884, Riordan's first full year in San Francisco, the Archdiocese contained 175 priests, 128 churches, and 25 chapels and stations to serve a Catholic population of 200,000.[21] Following his death in December 1914, there were 367 priests, 182 churches, 94 chapels and stations, and 94 parochial schools for 280,000 Catholics.[22] Many of the new parishes under his administration were established for immigrant communities.[1]

Riordan was considered a liberal churchman for his time. Biographer James P. Gaffey noted that Riordan's "closest friends were numbered among the so-called progressives or 'Americanizers,' such as Gibbons, Ireland, Keane, and Spalding."[23] In 1890, the conservative Archbishop Michael Corrigan, who had been Riordan's classmate in Rome, included Riordan's name on a list of liberal bishops, writing to Cardinal Camillo Mazzella: "In the ultra-Americanism of these prelates, I foresee dangers and sound the alarm."[24] Even after the Irish theologian George Tyrrell was excommunicated in 1907 for his Modernist beliefs, Riordan wrote of Tyrrell: "There is a place for him and plenty of work for him to do in this great Church of Christ."[25] In politics, however, Riordan was a conservative; during the 1912 presidential election, he strongly supported William Howard Taft over Theodore Roosevelt ("a disturber of the peace") and Woodrow Wilson (a "theorist").[26]

New cathedral and seminary

editTwo of the largest projects during Riordan's tenure were the erection of a new cathedral and seminary for the Archdiocese. Old St. Mary's Cathedral on California Street had been used since 1854, but in May 1883 Archbishop Alemany purchased land on Van Ness Avenue for a larger cathedral to serve the city's growing Catholic population.[27] The construction fell to Riordan, who laid the cornerstone in May 1887 and dedicated the new Cathedral of St. Mary of the Assumption in January 1891.[28] This cathedral would serve the Archdiocese for the next 50 years, until it was destroyed by a fire in 1962.[29]

A seminary had been established under Alemany near Mission San José (now Fremont) in 1883, but the seminary never had more than five students and collapsed within two years after the Marist professors left their posts.[30] Riordan received a plot of land in Menlo Park from the sister of the archdiocese's lawyer, and opened St. Patrick's Seminary as a minor seminary in September 1898.[31] Staffed by the Sulpician Fathers, the school became a major seminary with the additions of a philosophy department in 1902 and a theology department in 1904.[31]

APA and Father Yorke

editIn 1894, Riordan protested against the use of Outlines of Mediæval and Modern History by Philip van Ness Myers in San Francisco's public schools,[32] claiming the book was anti-Catholic and declaring it was "utterly unfit for use in a school patronized by children of various creeds."[33] In April of that year, the San Francisco Board of Education ruled that the book would still be used but allowed teachers to omit any passages that might "appear in any way to favor or to reflect on the particular doctrines or tenets of any religious sect."[34]

Although the book was ultimately retained, the school board's decision to grant discretion to teachers was denounced by some Protestant leaders in San Francisco,[35] including Rev. Charles Oliver Brown, who described the decision as "a complete surrender to Rome."[36] This response, and the growing presence of the anti-Catholic American Protective Association in the city, led Riordan to appoint his chancellor, Rev. Peter Yorke, as editor of the archdiocesan newspaper The Monitor to respond to Protestant attacks.[37] A local chapter of the Catholic Truth Society was also established in 1897.[38]

While Yorke proved popular among local Catholics, Riordan soon lost patience with the priest's increasing political involvement and attacks on elected officials like James D. Phelan and James G. Maguire.[25] Riordan eventually removed Yorke from The Monitor in October 1898.[25] Riordan initially made a very brief statement on the situation, saying only that "Father Yorke is alone responsible for his utterances,"[39] but later elaborated: "[T]he right must be accorded to [Yorke] as to every other citizen to make public his views on the rostrum or in the newspapers of the country...The Catholic Church does not dictate to its priests or its people the policy which they should adopt in political matters."[40]

Pious Fund

editRiordan played a significant role in the first case that came before the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, which centered on the Pious Fund of the Californias. Established in 1697, the Fund was an endowment paid annually by the Mexican government to sponsor missions in California.[41] Mexico stopped payments in 1848 following its war with the United States, but the American-Mexican Claims Commission later ruled in favor of the bishops of California in 1875, requiring Mexico to pay $904,000.[41] The decision, however, only covered the Fund's interest from 1848 to 1869 (when the Commission was created), and Mexico disputed its obligation to pay any interest accruing since 1869.[41]

In 1890, following the final installment of Mexico's $904,000 payment, Riordan asked U.S. Senator William Morris Stewart to seek diplomatic intervention by the U.S. government to obtain payment for the Fund's interest since 1869.[42] The State Department filed a claim for the unpaid interest in 1891 but there was no genuine progress on the case until 1899, when Secretary John Hay directed Ambassador Powell Clayton to reopen negotiations with Mexico.[43] In May 1902, the two governments signed a protocol by which the question of Mexico's liability would be submitted to the newly established Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague, the first case to be submitted to that tribunal.[42]

Riordan selected Edward Fry and Friedrich Martens as the U.S. arbitrators, with Senator Stewart serving as counsel.[44] The case opened on September 15, 1902, and concluded on the following October 14, when the court announced its unanimous verdict in favor of the United States.[42] Mexico was required to pay a sum of $1.4 million as well as a perpetual annuity of $43,000.[41] The U.S. government forwarded the award to Riordan and the bishops of California, withholding 35% to cover legal expenses.[42] Riordan was praised by Pope Leo XIII for his success,[45] and there were rumors that Riordan would be named a cardinal.[46]

1906 earthquake

editRiordan was in Omaha, Nebraska, on his way to an event in Baltimore, when a major earthquake struck San Francisco on April 18, 1906.[47] Among the Catholic Church's losses were more than a dozen churches and a number of other institutions, the damages totaling between $2 million and $6 million.[48] As he left for San Francisco on April 21, Riordan also telegraphed an appeal to every bishop in the country: "The work of fifty years is blotted out. Help us to begin again."[49]

Upon his arrival back in the city, Riordan celebrated open-air Masses for his displaced parishioners, who were living amidst the ruins in temporary shelters, and assured them, "We shall rebuild."[1] On April 27,[50] he addressed a committee at San Francisco's temporary city hall and quoted Paul the Apostle (Acts 21:39):

I am "a citizen of no mean city," although it is in ashes. Almighty God has fixed this as the location of a great city. The past is gone, and there is no use lamenting or moaning over it. Let us look to the future and without regard to creed or place of birth, work together in harmony for the upbuilding of a greater San Francisco.[51]

Riordan temporarily lived in San Mateo while providing his official residence to the Presentation Sisters, who had lost their convent on Powell Street.[52] Every church that had been destroyed had a temporary structure within two years and was rebuilt within another eight years.[52]

Later life and death

editIn 1902, nearly 20 years after he came to San Francisco as a coadjutor archbishop, Riordan received Bishop George Thomas Montgomery as his own coadjutor.[53] However, Montgomery died a few years later in 1907. To replace Montgomery, Riordan's preferred candidate was Edward Joseph Hanna, a theology professor at Saint Bernard's Seminary in Rochester, New York.[54] But Hanna's candidacy was derailed after his fellow professor, Andrew Breen, wrote a letter to Cardinal Girolamo Maria Gotti challenging Hanna's orthodoxy and accusing him of Modernism.[55][56] Riordan instead received Denis J. O'Connell, then rector of the Catholic University of America, as an auxiliary bishop in 1908 but he was later transferred to the Diocese of Richmond in 1912.[57] Riordan again submitted Hanna's name as coadjutor and finally succeeded in October 1912.[58]

In December 1914, Riordan contracted a severe cold which soon developed into pneumonia.[59] He died five days later at 1000 Fulton Street, the Archbishop's Mansion, his residence in San Francisco, aged 73.[59] He is buried in the Archbishops' Crypt at Holy Cross Cemetery, Colma. Archbishop Riordan High School in San Francisco, California, is named for him.

Episcopal succession

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d e f g The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. Vol. XV. New York: James T. White & Company. 1916. p. 248.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, pp. 2–3

- ^ Gaffey 1976, pp. 4–5

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 6

- ^ a b c d Shea, John Gilmary (1886). The Hierarchy of the Catholic Church in the United States. New York: Office of Catholic Publications.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 7

- ^ a b Gaffey 1976, p. 8

- ^ a b c d Andreas, Alfred Theodore (1885). History of Chicago. Vol. II. Chicago: The A. T. Andreas Company. p. 401.

- ^ "San Francisco". Catholic Encyclopedia.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 14

- ^ a b Gallery, Mary Onahan (1921). "Monsignor Daniel J. Riordan". Illinois Catholic Historical Review. IV.

- ^ a b c d e "Archbishop Patrick William Riordan". Catholic-Hierarchy.org.

- ^ Ellis, Elmer (1969). Mr. Dooley's America: A Life of Finley Peter Dunne. Archon Books.

- ^ McGovern, James J. (1888). The Life and Writings of Right Reverend John McMullen, DD First Bishop of Davenport, Iowa. Chicago: Hoffman Brothers. pp. 177–78.

- ^ "The Late Dr. Dunne". Chicago Evening Post. December 24, 1868.

- ^ "The Late Ex-Vicar-General Dunne". The New York Times. December 26, 1868.

- ^ a b Gaffey 1976, p. 33

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 43

- ^ "Name Dean Dunne Life Rector of Chicago Parish". The Herald-News. September 28, 1911.

- ^ a b Ellis, John Tracy (1952). The Life of James Cardinal Gibbons, Archbishop of Baltimore (1834-1921). Milwaukee: The Bruce Publishing Company. ISBN 0870611445.

- ^ Sadliers' Catholic Directory, Almanac and Ordo. New York: D.& J. Sadlier & Co. 1884. p. 195.

- ^ The Official Catholic Directory. New York: P. J. Kenedy. 1915. p. 236.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 178

- ^ Leahy, William P. (1991). Adapting to America: Catholics, Jesuits, and Higher Education in the Twentieth Century. Washington, D.C.: Georgetown University Press. p. 10. ISBN 9780878405053.

- ^ a b c McGuinness, Margaret M.; Fisher, James T. (2019). Roman Catholicism in the United States: A Thematic History. Fordham University Press. pp. 68–71.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, pp. 366–367

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 84

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 85

- ^ "HISTORY OF ST. MARY'S CATHEDRAL". Cathedral of Saint Mary of the Assumption (San Francisco). 16 November 2017.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, pp. 88–91

- ^ a b "ACADEMIC CATALOG 2012-2013" (PDF). Saint Patrick's Seminary and University.

- ^ The Pacific Unitarian. Vol. II (VI ed.). Pacific Unitarian Conference. April 1894. pp. 162–163.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 141

- ^ "THE SCHOOL BOARD: Settlement of the History Controversy". San Francisco Chronicle. April 12, 1894.

- ^ "Denouncing the Board: The Protestant Clergy Criticize the School Directors". San Francisco Examiner. May 14, 1894.

- ^ "Rev. Brown on the School Board". San Francisco Chronicle. April 23, 1894.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 146

- ^ "ORGANIZED TO SPREAD DIVINE TRUTH". San Francisco Examiner. November 30, 1897.

- ^ "Archbishop Riordan on Father Yorke". The Modesto Bee. November 3, 1898.

- ^ "THE PRELATE DIFFERS FROM THE PRIEST". San Francisco Examiner. November 3, 1898.

- ^ a b c d McEnerny, Garret (1911). "The Pious Fund of the Californias". The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. XII. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ a b c d Weber, Francis J. (1963). "The Pious Fund of the Californias". Hispanic American Historical Review. 43 (1): 78–94. doi:10.1215/00182168-43.1.78.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 219

- ^ Gaffey 1976, pp. 225–226

- ^ "POPE LEO PRAISES ARCHBISHOP RIORDAN". San Francisco Examiner. October 23, 1902.

- ^ "HAGUE TRIBUNAL DECIDES FOR ARCHBISHOP RIORDAN". San Francisco Examiner. October 15, 1902.

- ^ "PRELATE OF FRISCO HERE". Chicago Tribune. April 20, 1906.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 251

- ^ "ARCHBISHOP'S APPEAL". Oakland Tribune. April 21, 1906.

- ^ "CONFIDENCE IN SAN FRANCISCO BRINGING ABOUT ORDERLY ADJUSTMENT OF AFFAIRS". The San Francisco Call. April 28, 1906.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 251.

- ^ a b Gaffey 1976, p. 253

- ^ "Archbishop George Thomas Montgomery". Catholic-Hierarchy.org.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 282

- ^ "RIORDAN'S MISSION TO ROME A FAILURE". The New York Times. January 26, 1908.

- ^ "FATHER BREEN CRITICISED". The New York Times. January 28, 1908.

- ^ "Bishop Denis Joseph O'Connell". Catholic-Hierarchy.org.

- ^ Gaffey 1976, p. 315

- ^ a b "ARCHBISHOP RIORDAN DEAD; Pneumonia Kills Catholic Prelate—Head of San Francisco Diocese". The New York Times. 1927-12-28.

Sources

edit- Gaffey, James P. (1976). Citizen of No Mean City: Archbishop Patrick W. Riordan of San Francisco (1841-1914). Wilmington, Delaware: Consortium Books. ISBN 0-8434-0628-3.